INDIANS GET AIRBORNE

Indians were late entrants to the field. But we have made up for lost time, to a large extent. Of course, we are still much behind the developed nations. Finance stands in the way, not lack of spirit or enthusiasm or commitment. Yet many Indians have overcome the limitations, created aviation history. It is impossible to refer to all of them. However the feats of three Indians, detailed in this section, make us swell with pride.

The first Indian to dare to fly was Jahangir Rattanji Tata. He was drawn to it when he was hardly ten. He stood at the beach, on the French Coast, close to where he lived with his parents and let his eyes rivet on a small plane in flight. The drone of the aircraft became louder as it came near, started to descend and touched down on the sand. The pilot hopped out of the cockpit.

"Uncle", Jahangir screamed when he identified the pilot, Bleriot, a neighbour and a family friend. He was the first man to fly across the English Channel. Jahangir held him by the hand and looked at him with admiration. "How I wish I too could fly!" the boy turned hopefully to the elder.

"Meet me here tomorrow at 10. I shall take you on a joy ride", said Bleriot.

Next day the boy had his first flight. "Some day, Uncle, I shall fly my own plane", said the boy.

"Why not!" Bleirot gave the boy an encouraging nod.

"Can I fly planes?" the boy asked his parents, later in the day.

"Of course! Flying can be a hobby," his father, Ratanji Dadabhai Tata, held him in a warm hug.

In 1929, Jahangir received the pilot’s licence. In 1930, he made a bid for the Aga Khan Trophy, offered to the first Indian who flew solo from India to Britain or from Britain to India, in the shortest time. Jahangir (better known as JRD), entered the race, took off in a Puss Moth aircraft and flew West, heading for Britain. Around the same time, another young man, Aspi Engineer, set out from Britain and headed for India.

JRD ran short of fuel, while flying over Egypt, and force-landed in the desert. He trekked to an outpost at Rutbah Wells, once an important stop on the Imperial Airways’ route, gathered fuel and returned to resume the flight. At the next stop, on the desert route, he met Aspi Engineer. JRD greeted him warmly. Aspi grinned, but his eyes wore a beaten look.

"What is troubling you, Aspi?" JRD asked.

"I need spares, but where will I get spares in this desert? I think I have to drop out of the race", Aspi scowled.

"Cheer up, Aspi. I have some spares with me. Come, take what you want", JRD gently picked up Aspi’s hand.

Aspi jumped with joy, thanked JRD, picked the spares he needed, carried out the repairs and tested the engine. "Good luck", said JRD.

Soon both resumed their flights. JRD headed West; and Aspi flew East. Both completed the trip. But Aspi recorded better timing and won the race.

"I owe my success to JRD", he said. "But for those spares, I would never have made it".

Aspi was at the airport when JRD landed at Karachi. JRD stepped out of the cockpit and ran into the warm hug of Aspi. His eyes opened wide when Aspi asked him to

accept a guard of honour, presented by a group of boy scouts. Aspi had specially brought them to the airport to make the welcome memorable. That was perhaps the best homecoming that JRD ever had!

Many years later, JRD noted, "I am glad that Aspi won because it helped him into the Air Force". Aspi rose to high ranks, retired as the Chief of the Indian Air Force.

JRD joined the family’s business house (Fig. 11.1). In between, he took time to fly planes. Around that time, the Imperial Airways planned a flight between London and Calcutta via Karachi. A friend,

JRD joined the family’s business house (Fig. 11.1). In between, he took time to fly planes. Around that time, the Imperial Airways planned a flight between London and Calcutta via Karachi. A friend,

Neville Vintcent, a dare devil flier from Britain, saw a golden chance.

He suggested to JRD, "Why don’t you start an airline service linking Bombay with Karachi?" JRD discussed it with Uncle Dorab. "No",

roared the old man. But JRD kept up pressure. Finally he received the green signal. Tata Aviation service was formed.

The service started with a solo flight by JRD on 15 October 1932. He took off from Karachi, in a single-engine Puss Moth, flew solo, bringing mail to Bombay. It was a historic flight. The Airlines grew in strength. In 1948, it became Air India International. After nationalisation, the government appointed JRD as the Chairman.

In 1982, he celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his first flight, flying the same route in a De Havilland Leopard Moth. That was indeed a record.

Vijaypath Singhania, a 49-year-old industrialist of Kanpur, chose another track to create a record. He too loved flying, knew how aviation had grown through the years since the

flight by the Wright brothers in 1903.

One day, while going over the records in aviation, he felt depressed. ‘India does not have any aviation records’, he moaned. How he wished someone would accept the challenge and create aviation history? Then it struck him. Why shouldn’t he himself accept the challenge?

Easier said than done. But Vijaypath was equal to the task. He resolved to carry out the plan. His search for possible records to create or break led him to the feat of Brian Milton, a journalist. Milton had flown a microlite aircraft, solo, from Britain to India, in 34 days. Could he fly the distance in lesser number of days and thus create a new record? That seemed a target he could achieve.

He looked out for a microlite aircraft that would serve him well. Finally, after going round Aircraft factories all around the globe, he chose an aircraft manufactured by a British firm. It weighed just under 150 kg (6.4 m long; wingspan 10 m and maximum sped of 60 knots). He named it L’esprit d’lndian Post.

Preparations began in right earnest. The aircraft was readied for the 9600 km flight to Delhi. The maximum distance that the single engine aircraft could fly, non-stop, was 960 kmph. The route and the scheduled halts enroute were meticulously chalked out. Medical facilities were lined up at the halts to provide for emergencies. Landing permits at various proposed stops were obtained. Due note was also taken of the dangers posed by the turbulence over the Mediterranean Sea and over the Gulf of Oman.

On 15 August 1988, Vijaypath took off from Biggin Hill, outside London. Clouds blinded him while he flew over the Alps. He had to descend below the clouds, fly rather very low, hardly 100 m, along the coast of Italy, to avoid the mist. The fuel tank cracked and gave some anxious moments. But he safely landed at the next stop and set it right. While crossing the Mediterranean, he had his life jacket on and

carried a shark repellant. "Every time I would spot a ship, I would start calculating how long it would take the vessels to reach me if I fell", he joked.

The aircraft ran into a crosswind and was tossed around, giving him many anxious moments. Overflying the Saudi desert, the plane got caught in sandstorms. It required all his skill to steer the plane through. When he landed, the wind was so strong that the aircraft came to a dead stop in just under 4 m. Occasionally technical snags delayed his plan. At one stage, he was behind the time set by Milton by about two days. But he made up for lost time, thanks to some fine weather. He landed at Ahmedabad, 21 days after taking off from London, to a rousing reception. He had beaten Milton’s record by 11 days.

The nation hailed his feat. JRD was at the tarmac of Safdarjang Airport, on 11 September, to welcome him. Milton too was present. He complimented Vijaypath on breaking his record. Vijaypath had raised India’s image.

Harji Malik was one of the first Indians to be commissioned in the Royal Air Force. After independence, the Indian Air Force came into being. It played a major role in defending the nation. The officers and men displayed exceptional gallantry on the battlefield. Among them the name of Flying Officer Nirmaljeet Singh Sekhon stands out (Fig. 11.2).

It was 14 December 1971. India was at war with Pakistan. A Gnat detachment was moved to Srinagar. A 25-year-old ace pilot, Sekhon, who had flown the Gnat on several missions, was standing at the window of the duty room at Srinagar. He drew the collar closer as the chill wind wafted in. Then he heard the deafening scream of the siren. He noticed four Fig u 2. sekhon

It was 14 December 1971. India was at war with Pakistan. A Gnat detachment was moved to Srinagar. A 25-year-old ace pilot, Sekhon, who had flown the Gnat on several missions, was standing at the window of the duty room at Srinagar. He drew the collar closer as the chill wind wafted in. Then he heard the deafening scream of the siren. He noticed four Fig u 2. sekhon

Pakistani Sabres zooming toward the airport. Behind these planes came two more. The enemy aircraft bombed the airport. Four of the ten aircraft held at the airport were damaged.

"I will get you, for sure", Sekhon swore, while he sped to the hangar. He neared one of the gnats that had not been damaged. He found Srawan Singh, an airman, bleeding, badly hurt, yet boldly checking the aircraft, and asked him, "Is this aircraft fit to fly?" The man nodded his head.

Sekhon got into the cockpit. "Take my advice. Don’t go after them. There are six of them. You can’t hunt them down", the man warned, before collapsing.

Sekhon started the engine. He got clearance to take off and was soon in flight. He went after the Sabres. He spotted two of them, flying low, almost scraping the tops of trees. He took them by surprise. His guns boomed before the enemy knew what was happening. The two Sabres were hit. They spun like leaves, caught in a storm, and crashed.

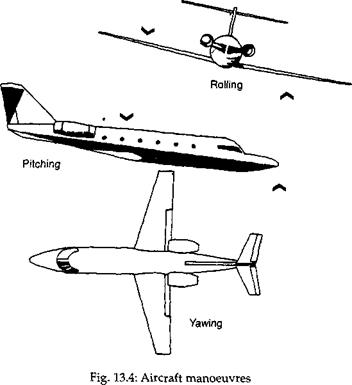

Sekhon steadied the Gnat at a height of 200 m and looked out for the remaining four Sabres. He knew that he no longer enjoyed the advantage of taking them unawares. He saw in the rear mirror three Sabres coming after him. He quickly set the Gnat on a back roll. The enemy pilots didn’t anticipate that move. They banked to the right. Sekhon got just enough time to shoot one of them down. The other two regrouped and charged. This time Sekhon could not avoid a direct hit. The tail of the aircraft burst into flames. The engine went dead. The left wing caught fire and fell off. Sekhon took a deep breath as the plane started to plunge. Then his eyes lit with joy. He noticed the tracers fired by ack-ack guns on the ground, tearing the bellies of the Sabres. He was still savouring this sight when his plane hit the ground. Sekhon died with a smile on his lips.

The nation honoured him with the Param Vir Chakra.

12

The first name that comes to mind is of Sir George Cayley. He tracked down the forces that needed to be controlled before one could fly. These were Tift, drag, thrust and gravity’. He developed the controlling mechanisms to counter-balance these forces and thus provide balance to the flying object. He shaped the horizontal rudder (or elevator), experimented with multiple-wing designs, thought of the propeller. For over forty years, he worked. Finally, in 1849, he decided to test fly his tri-plane glider. He strapped a 10- year-old boy on to the glider and tested it at the open grounds close to his home Brompton Hall. The glider soared in space.

The first name that comes to mind is of Sir George Cayley. He tracked down the forces that needed to be controlled before one could fly. These were Tift, drag, thrust and gravity’. He developed the controlling mechanisms to counter-balance these forces and thus provide balance to the flying object. He shaped the horizontal rudder (or elevator), experimented with multiple-wing designs, thought of the propeller. For over forty years, he worked. Finally, in 1849, he decided to test fly his tri-plane glider. He strapped a 10- year-old boy on to the glider and tested it at the open grounds close to his home Brompton Hall. The glider soared in space.

Remember Burt Rutan who designed the Voyager? In December 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeagar flew the aircraft, round the globe, non-stop and created history. Now (in January 2005), Steve Fossett—the first person to circumnavigate the globe solo in a balloon—is all set to perform a similar feat. He will be flying the aircraft GlobeFlyer—solo— designed by Burt. The flight is expected to be completed in 70 hours.

Remember Burt Rutan who designed the Voyager? In December 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeagar flew the aircraft, round the globe, non-stop and created history. Now (in January 2005), Steve Fossett—the first person to circumnavigate the globe solo in a balloon—is all set to perform a similar feat. He will be flying the aircraft GlobeFlyer—solo— designed by Burt. The flight is expected to be completed in 70 hours.