ONE MAN’S COURAGE

The success of Alcock and Brown was historic. Now came the question: Could anyone fly the Atlantic solo? Charles Lindbergh accepted the challenge (Fig. 6.1). He made all preparations and arrived at New York in May 1927. He was keen to fly his aircraft, the Spirit of St. Louis, across the Atlantic, all the way from New York to Paris, solo. He had set his heart on it. But bad weather had forced him stay put for about a week. All through the night of 20 May he tossed in his bed. He could not get a wink of sleep.

Many friends asked him why he wanted to stake his life on the risky venture. He laughed off their fears. "I’ve designed this plane. It can carry enough fuel to last me for the journey. I may have some to spare too, at the end of the journey. As regards my decision to fly solo, well, I’d be better off with more asoline than an extra man", said Lindbergh.

Many friends asked him why he wanted to stake his life on the risky venture. He laughed off their fears. "I’ve designed this plane. It can carry enough fuel to last me for the journey. I may have some to spare too, at the end of the journey. As regards my decision to fly solo, well, I’d be better off with more asoline than an extra man", said Lindbergh.

"Yet, it’s risky", said his friends.

That was true. Rene Fonck, a veteran of France (he had been a fighter pilot during World War I), had tried and failed. His plane crashed at take off. Noel Davis and Stanton Wooster, two Americans, died in a mishap during a test flight. Charles Nungesser and Fig. 6.1: Charles Lindbergh

Francois Coli, two war heroes of France, took off from Paris on May 8, 1927. They vanished into thin air. Nobody knew what happened to them.

These failures didn’t scare Lindbergh. They only spurred him on, strengthened his determination to go ahead with his plan.

He was just 25. He was ready to dare and act. He wanted to be the first to fly an aircraft, solo, across the Atlantic. It was truly a quest he loved. Success would bring him name and fame. There was also the lure of the prize money ($25,000), offered by a rich hotel magnate Raymond Orteig.

These were factors that weighed with him. But hardly anyone guessed why he was so hell-bent on executing this plan. Years later, he shared it with the whole world, "I have never been aware of the need to prove myself… . My impression is that I have done what I have done because I enjoyed doing it or because I thought it led to some desirable or necessary end".

He fell in love with flying after he watched an air show at Fort Meir. "How exciting would it be to soar freely, up in the air, like birds?" thought Lindbergh. From then on, flying became a passion. Lindbergh chose flying as a career. He told his father of his decision. The old man demurred, "Flying is dangerous and you’re my only son". Lindbergh pleaded. Finally, the old man agreed.

Lindbergh’s mother was more understanding and supportive. She patted him and said, "If you really want to fly, that’s what you should do". Lindbergh danced with joy.

From then on, nothing could hold him back. He trained to fly. There was money in flying. He earned his living, carrying passengers around. He hopped around, flying mail. In between he found time to practise parachute jumping.

Every success in the field of aviation thrilled him. Each report fired his imagination, gave wings to a desire.

He resolved to strike yet another milestone in the history of aviation.

But what could he do? The answer came to him while flying an airmail sortie in the fall of 1926. Suddenly he remembered the prize money offered by Orteig to one who flew an aircraft solo across the Atlantic, all the way from New York to Paris and set a new record in the annals of aviation.

One major problem stood in his way. He didn’t have enough funds to take on this project. All that he could raise were $2,000. He needed more than $35,000, to get an airplane and to make other preparations.

Where would the funds come from? There were many rich businessmen and industrialists who often sponsored such endeavours. They had the money and the will to give liberally to help the daring.

Lindbergh approached a few rich friends and acquaintances. He explained what he had in mind. He handed over to them detailed break-up of the funds he needed and justified every item of expense.

Many people showed interest initially. Most of them, however, shied away. Finally, Harry Knight and Harold Bixby of St. Louis gave him the green signal.

The search for the ideal airplane began right away. Lindbergh was clear of what he wanted. He noticed that earlier attempts by experienced pilots, who flew doubleengine aircraft, had failed. He decided, then, to fly a singleengine airplane. He decided on a Ryan monoplane.

He sent a wire to Ryan, the airplane builder of San Diego:

CAN YOU CONSTRUCT A WHIRLWIND ENGINE PLANE CAPABLE OF FLYING NONSTOP BETWEEN NEW YORK AND PARIS? If SO, PLEASE STATE COST AND DELIVERY DATE.

Ryan discussed the finer details. Lindbergh explained "I would like to carry maximum fuel. I’ve to fly a distance of about 3,500 miles (5,400 km) nonstop. If I run short of fuel, I’ll be in trouble".

"What about safety?" Ryan asked.

"Safety at the start of my flight means holding down weight for the take off. Safety during my flight requires plenty of emergency equipment. Safety at the end of my flight demands ample reserve of oil. It’s impossible to increase safety at one point without detracting from the other", Lindbergh defined his analysis of safety.

Ryan understood. Lindbergh was giving maximum attention to safety at the end of his flight. He was hinting that he would sacrifice safety at take off and during flight to ensure he reached his goal. He would take as much fuel as he could. If some safety equipment had to be offloaded, so be it. The radio set, used for communication, became the first casualty. That provided space for 35 kg of fuel. The sextant was discarded. "I’m on a solo flight. Where will I’ve the time to adjust and read the sextant?" he asked.

Reducing weight became an obsession. Lindbergh ripped spare pages off his notebook. He cut holes in the world map, clipping out places not on his route. He procured special lightweight shoes. He didn’t take a parachute along. That gave room for 9 kg more of oil. He cut down on the food and water supplies too. He carried only five sandwiches and a quart of water. That was very frugal fare for a long flight of about 35 hours. Lindbergh knew it. Yet he opted for it, saying, "If I get to Paris, I won’t need any more; and if I don’t get to Paris, I won’t need any more".

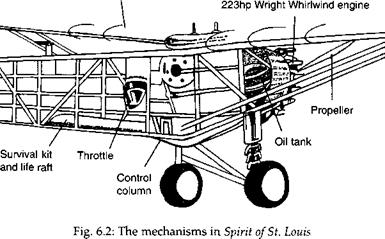

The fuel tank went in front. It blocked his vision. Lindbergh didn’t consider this a major problem. In those days, the airspace was uncluttered. No aircraft flew the route. However as a measure of caution, he fixed a periscope. It poked out on the left side. The view taken by the periscope was displayed on the instrument panel. Lindbergh believed that he would be safer, with the fuel tank in front of him. A

|

Wing fuel tank

|

clock, a compass, an altimeter and an air speed indicator were the other equipment he had on board (Fig. 6.2).

At 2.30 a. m., on 20 May, Lindbergh looked out through the window. The star-studded sky winked at him. Was it a signal to him to set out on his historic flight?

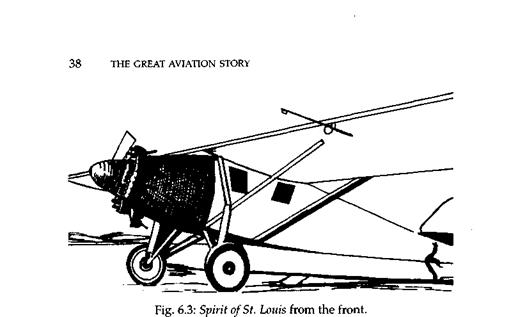

He jumped out of bed, took a quick bath before driving down to New York Airport. He checked the airplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, before taking in fuel (Fig. 6.3). "Load it up to the last ounce", Lindbergh grinned.

He got into the cockpit, started the engine, pulled the throttle. The aircraft started off, slowly. It picked up speed, but till it neared the end of the runway, it looked as if it might not get airborne. The ground crew gasped in fright. But the miracle happened. To the relief of everyone, the aircraft lifted off, just at the last moment. It flew inches above electric poles and trees, before gaining height.

A mild easterly wind held course. Lindbergh headed toward Nova Scotia, and thence to Cape Breton Island. Heavy rain, fog and turbulent weather made flying

difficult. For a moment, Lindbergh was tempted to consider whether he should call off his mad plan and seek security at St. John. Beyond St. John lay thousands of miles of sea. Once he left St. John behind, he would have no option but to fly ahead to his destination or be ready to be dumped into the Atlantic.

With grim determination, he circled St. John and flew out toward the sea. He sighed in relief. He saw the advantage that this choice held out. "A pilot, who has 2,000 miles of sea ahead of him, can’t park his plane on a cloud bank to weather out a storm or heave over a sea anchor like the sailor and drag along slowly down wind. He’s unable to control his speed like the driver of a motor car in fog. He has to keep his craft hurtling through air, no matter how black the sky or binding the storm", he told himself.

He rose to 10,500 feet (3,250 m) to get above the fog. The air around was very cold. Icy clouds were all around. "They enmesh intruders. They’re barbaric in their methods. They toss you in their hailstones, poison you with freezing mist. It would be a slow death, a death one would have long minutes to struggle against—climbing, stalling,

diving, whipping, always downward toward the sea", Lindbergh recollected about this experience. Quickly, he got out of the icy clouds. He descended before ice coated the wings and made the airplane heavier.

After 17 hours of flying, Lindbergh felt terribly sleepy. His eyelids drooped. He pulled the window so that ice cold wind hit his face. He slapped himself. Once he dozed off. The plane took an ugly roll, jerking him out of sleep. He saw illusions—of bottomless seas, of towering mountains, of rolling cascades. He feared of straying off the route.

The sun rose. With it came a sense of relief and confidence for Lindbergh. He had been airborne for 24 hours. The sleepiness vanished. He felt fresh and full of energy.

He flew on. Two hours later, he saw a seabird in flight. Then he saw a few native boats, sailed by fishermen. For Lindbergh that was a welcome sign. Land could be close by. Was he heading toward the Irish coast? He flew lower, hoping to find out from the fishermen on the boats. He shouted, "How far is the Irish cost?" Nobody heard his call.

|

After circling around the boats for a few minutes, Lindbergh realised it was a waste of energy. He was burning up fuel on a futile quest. Swiftly, he changed course and headed toward his goal. Soon, he flew over the Irish coast. He was two hours ahead of schedule. That meant he had enough fuel to fly beyond Paris. Should he fly to Rome?

Fig. 6.4: Lindbergh’s route across the Atlantic

For a moment, he toyed with the idea. Then he gave it up. He had set out for Paris. To Paris would he go (Fig. 6.4).

Joy filled his heart as he neared Paris. In ecstasy, he told himself, "The Spirit of St. Louis is like a living creature, gliding along smoothly, happily, as though a successful flight means as much to it as to me. We love this flight across the ocean, not I or it".

The airplane circled the airport, lit by a thousand lights (Fig. 6.5). However, darkness obscured the aircraft till it descended and came within the range of the lights. The touchdown was smooth. Lindbergh’s solo flight across the Atlantic had taken 33 hours and 39 minutes.

A large crowd encircled him as soon as he got out of the cockpit. "Thousands of men and women were breaking down fences and flooding past guards", he recollected in his memoirs.

Walter S. Ross described the scene, "Lindbergh opened the door to climb out, but he didn’t set foot on ground.

|

Fig. 6.5: The darkened runway in Paris was illuminated by the headlamps of cars. |

Hands reached out and pulled him out. He was spread – eagled on top of the crowd like a captive tortoise". Two French pilots, Detroyat and Delage, quickly snatched the soft leather helmet of Lindbergh and made a tall American, who was standing a little away, wear it. The crowd mistook him for Lindbergh and encircled him. That gave the chance to the two pilots to lead Lindbergh away to a Renault car waiting to take him away.

He received a hero’s welcome in European capitals. President Coolidge honoured him with the Distinguished Flying Cross. Time-Life Books, in their series, This Fabulous Century, covering the period 1920-1930, wrote, "When a lanky, soft-spoken youth named Charles Lindbergh made the first solo airplane flight nonstop from New York to Paris, America pulled out the stops. As he was escorted up Broadway, jubilant crowds showered the returning hero with 1,800 tons of shredded paper".

The accolade was his by right. He had flown solo across the Atlantic, proved that man could overcome every challenge that came his way. However there was still one challenge to be met. Nobody had flown across the Atlantic, from Europe to America.

In May 1927, a Parisian newspaper carried a report, claiming that the L’oiseau Blanc, piloted by Francois Coli and Charles Nungessser, of France, had crossed the Atlantic, flying East to West. This turned out to be wrong. The aircraft vanished shortly after take off. There was no trace of the aircraft or the men on board. Undaunted by this tragedy, Hermann Koehl, a former German Air Force pilot, undertook the flight. The Junkers Airplane company placed an all-metal low-wing W-33 monoplane at his disposal. Baron Gruenther von Huenfeld offered financial support on condition he was taken along as passenger. James A. Fitzmaurice, an Irish pilot with immense experience agreed to be the copilot.

The aircraft, called Bremen, took off, shortly after dawn, on 12 April 1928, from Baldonnel Airport, near Dublin. Strong headwinds slowed down their progress. Throughout the night, the aircraft was adrift in fog. Even after the day broke, the fog held on. The plane drifted too far north. Then came a blizzard. For four hours, the plane was tossed around. When it abated, the engine developed a leak. Koehl checked. The fuel gauge hovered around the empty mark. New York, their original target, was far away. So the pilot opted to land at Greenly Island, a barren stretch between Labrador and New Foundland. The three men had flown the Atlantic, from East to West. They had put yet another challenge down under.

Then came the daring dame, Amelia Earhart. She proved that women could match the men in grit and tenacity.