Peace claimed its victims. The victims were young, daring fighter pilots. They were demobilised, knocked out of action. But the knocks did not leave them down and out. Many of them found new areas of activities.

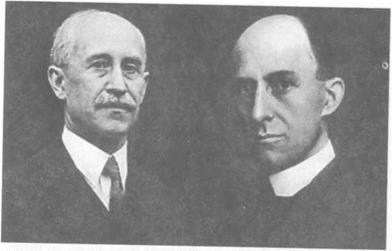

John Alcock and Arthur Witten-Brown had served the Royal Air Force as fighter pilots (Fig. 5.1). They did not like being grounded. How could they get a chance, once again, to fly?

Alcock heard, while spending an evening at the club, in late 1918, with a friend, of a prize of 10,000 pounds offered by the Daily Mail to the first person to fly non-stop across the Atlantic.

"This is one flight I can undertake. If only I can find a sponsor, who gets me an aircraft and also provides funds to equip it…" Alcock didn’t complete the sentence.

"This is one flight I can undertake. If only I can find a sponsor, who gets me an aircraft and also provides funds to equip it…" Alcock didn’t complete the sentence.

"That shouldn’t be a problem", the friend mumbled.

"So, where do you see a problem?" Alcock said edgily.

"It’s a mission fraught with danger", the friend warned.

"That’s the least of my Fig – 5.1: John Alcock and worry", Alcock Smiled wryly. Arthur Witten-Brown.

"I’ll make a bid, if I get necessary backing", Alcock replied.

He discussed the matter with Arthur Witten-Brown, a former RAF fighter pilot, and asked, "If I ask you to fly with me?"

"I’ll jump at the offer", Brown responded with joy.

"That’s a deal", Alcock reached out for Brown’s hand.

A checklist of possible patrons was prepared. This list helped them find support for their project.

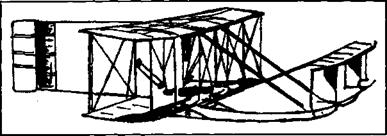

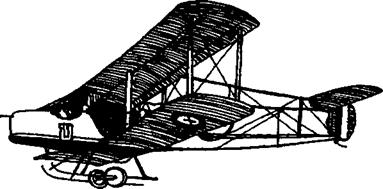

Which aircraft should they fly? They remembered the Vickers Vimy biplane, which they had flown during the war on bombing missions. It was a large plane, powered by two Rolls-Royce engines. It had speed and strength.

"WeTl have to fly from the American end", pointed out Brown.

"I know. Air currents make a flight, across the Atlantic, heading toward Europe, easier", Alcock smiled.

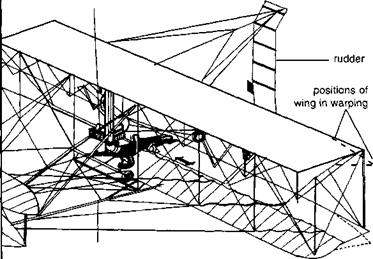

The two got hold of a bomber, dismantled it and carted it, in sections, to St. John’s, New Foundland, and set up camp (Fig. 5.2). The site for assembling the aircraft lay at an open ground called Mundy’s Pond. The two secured assistance of a handful of enthusiastic mechanics and reassembled the aircraft. They attached additional fuel where the aircraft once ’ carried bombs. Some space for storage of fuel was provided in the wings too (Fig. 5.3).

|

Fig. 5.2: Vickers Vimy bomber

|

While these preparations were under way, the American Navy launched a hopping flight across the Atlantic. Curtiss co-ordinated the technical details of the flight. Lt. Commander J. H. Towers led the group of four seaplanes.

Seaplanes and flying boats take off and land on water. Due to lack of runways, normal airplanes could not operate as passenger carriers. The seaplanes and the flying boats, therefore, were used extensively to transport people around till about 1950.

The seaplanes set out on 8 May 1919. One of the planes developed problems and dropped out. The others, after a few halts, reached Lisbon on 20 May. A week later, they flew to Plymouth, England. It was not a non-stop flight. So Alcock and Brown were not unduly upset.

Cause for worry came from another source. At St John’s, two daring pilots, Harry G. Hawker and Mackenzie Grieve, were making the final preparations to fly a single-engine Sopwith biplane across the Atlantic. They set out on 18 May 1919. Alcock and Brown cursed their fate. Had they come so far, only to be beaten in the race by their competitors? That thought nagged them, while they waited for further reports of the flight of the Sopwith.

Harry G. Hawker and Mackenzie Grieve flew toward the Irish coast. The engine coughed and spluttered after covering about 1,800 km. The deep blue stretch of the sea menacingly closed in as the plane lost height and tumbled into the waters. A tramper rescued the bobbing men from the waters. Thus ended their bid for the prize.

The news lifted the spirits of Alcock and Brown. They hurried with the final preparation.

14 June 1919 was a bright sunny day. Reports indicated that the weather would hold, for some time. Of course, nobody took such predictions seriously. The weather could turn bad, suddenly, without warning. The two pilots got into the cockpit. Alcock started the engine. He pulled the throttle. The aircraft raced along the bumpy, uneven field. The wings, laden with fuel, drooped. The aircraft lifted off, sluggishly, just a few feet before it reached the block of trees that circled the field. The aircraft skimmed inches above the trees.

For a couple of hours, the aircraft was nudged faster by the tailwind. That gave an added 64 kmph to the normal cruising speed of 145 kmph of the aircraft.

The first setback for the fliers came when the radio conked off. Thus the plane’s communication line was snapped. Soon, the airplane began to rattle. A quick check by Alcock made him shiver. The exhaust of the right engine had cracked. It was quivering as if mad, while tongues of flame danced around the crack. For a moment, Alcock thought it marked the end of their mission. Then hope surged up. He told himself, "We’ve weathered many a storm, during the days in the RAF. So, even this threat may pass".

It did pass. But soon the plane ran into massive air turbulence. Vertical air currents spun the plane, viciously. The plane lost height. It came as close as 20 m of the sea. Alcock pulled at the stick, frantically. The plane quivered. Then its nose rose and Alcock and Brown sighed in relief. The plane regained altitude.

John Alcock steered the plane above the clouds and the fog. The plane faced a new danger. Sleet and snow hit the plane.

The roar of the engines was loud.

The roar of the engines was loud.

The two men could not even talk to each other, find out how they could face the threat.

Brown acted on his own. He grabbed a knife and climbed out of the cockpit, crawled over the right wing, got close to the engine and scraped the blocks of ice that coated the engine (Fig. 5.4). Back he went to repeat the operation with the second engine. It was a very risky operation. A sudden gust of wind, a surge of air current would have sent Brown plummeting into the icy waters, below.

Alcock decided to fly at a lower altitude. The fog had cleared. For seven hours, the weather tested the limits of endurance of the pilots.

At last, it was day. Visibility was good. Brown scanned the scene ahead of him. Suddenly the southern tip of Ireland came into view. Brown could not contain his joy. He screamed, above the roar of the engines. But, Alcock could not make out what he was saying. He could only notice Brown holding out the hand, pointing toward a hazy curved line beyond the waters. The sea seemed to be kept back by the hazy line. Beyond the line lay land, the Irish coast. That

awareness touched his lips with a thin smile.

Alcock checked the maps, read the compass and made quick calculations. The plane was heading toward the small town of Clifden, some distance off Galway, the original target the pilots had set.

Alcock circled the land. Brown spotted a vast ‘open ground’. Alcock started the descent. The aircraft touched down, in the centre of a muddy patch. The wheels of the aircraft lay buried in mud. Quickly, the two men on board the aircraft got out, splashed their way through the mud and reached firm ground. "That’s it", Alcock hugged Brown. The two stood, with tears of joy streaking down their cheeks. It was their moment of triumph. They had crossed the Atlantic without a halt in between.

This triumph made them heroes. Wherever they went, large crowd mobbed them. Young boys and girls crowded around them, seeking autographs. Cameras clicked, catching their profiles on films for eternity. They received the prize money. That cheered them. But happier still were they when the King of England knighted them, at a special function at the Buckingham Palace.

In 1914, the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated. The tragedy rocked the whole of Europe. War clouds gathered. Efforts to avert a war failed. The Astro-Hungar – ian Empire, Germany and Turkey, formed a group. Pitted against them were the Allies, composed of Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Japan and the United States. First World War broke out.

Nations at war have, since time immemorial, adopted many strategies to gain their ends. Among them, the effort to gather information about the enemy’s strength and formation remains vital. It was so during the First World War too.

Field scouts fanned out, sneaked, as close as they could, to the enemy lines. They stayed beyond the firing range of the enemy, watched through telescopes and gathered information.

Manual scouting almost ended when machine guns, invented by Fliram Maxim, came into use. The enemy defended his camps with machine guns. The scouts could not get close enough to gather information.

On earlier occasions, balloons had been used for aerial survey of enemy positions. Could not aircraft perform the job better? The possibilities seemed immense. Both sides started working on this idea. The existing aircraft were redesigned. Additions and alterations made them sleeker, faster and easier to fly. The cameras on board recorded

enemy formations and camps while the aircraft flew at heights well beyond the range of guns on the ground. Aerial reconnaissance became the order of the day.

How could enemy snooping be stopped? Instructions were issued to designers of aircraft to come up with ways and means to stop the predators. They considered various options and finally came up with a single-seater fighter aircraft, equipped with guns, to intercept and down enemy aircraft, engaged in aerial survey.

This was just the beginning. Soon came a brilliant idea. Can’t single-seated aircraft fly over enemy territory and drop bombs? That marked the birth of bombers. New designs improved the speed and manoeuvrability and fighting power of the aircraft.

This was just the beginning. Soon came a brilliant idea. Can’t single-seated aircraft fly over enemy territory and drop bombs? That marked the birth of bombers. New designs improved the speed and manoeuvrability and fighting power of the aircraft.

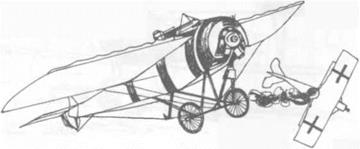

The air was no longer a safe place. In March 1915, Raymond Saulnier invented a bullet deflection device (BDD). It was tacked to the propeller of a monoplane. Powered by a rotary engine of 110 hp, it had a maximum speed of 165 kmph and flew at an altitude of 2000 m. The

BDD timed the gun to fire when the Fig. 4.1: Rolland Garros

|

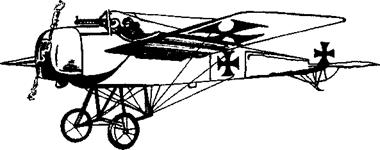

Fig. 4.3: Fokker monoplane

|

rotating blades were not in the way of the gun. This device proved very effective. Roland Garros (Fig. 4.1), a French pilot, used this device to shoot down three enemy aircraft during one mission (Fig. 4.2).

The Germans were not far behind. They developed the Fokker, a small aircraft (Fig. 4.3). Its top speed was 130 kmph. A fleet of 50 such aircraft went into action against the Allies. They turned out to be a real scourge. Aerial bombing caused severe damage to people and property. The English and the French reeled under the attack.

German designers produced special types of aircraft to serve specific needs. Training for pilots became scientific

and systematic. Pilots mastered the art of flying in formation. This led to development of Squadrons with defined duties. Repair centres were also set up. Germany continued to make headway in exploiting the air power.

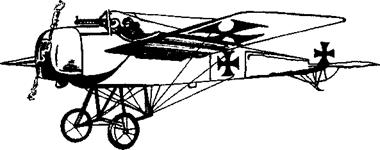

Britain and France found the answer to the Fokker aircraft in new designs. In 1915, Capt. Geoffrey de Havilland produced the D4-2. It could fly at a speed of 140 kmph. The Fokker could not match it in speed and dexterity. The Germans, in turn, improved on the French aircraft Neuport and produced Albatros D-l (Fig. 4.4). It had dual machine guns, with double the fire power, mounted near the cockpit. The Albatros carried out attacks on Britain in April 1917. (Historians refer to the period as Bloody April). England lost 151 planes; Germany just 51. German bombers, called Gothas, carried out aerial bombing even during the day. The Allies were unequal to this assault. The chances of holding back Germany looked bleak.

Then came the turn of fortune. The United States joined the Allies. Britain designed the Sopwith Camel, an excellent fighter aircraft (Fig. 4.5). The Bristol Fighter and Spad XIII were two new aircraft that strengthened British air strength. Germany refined the Fokker to produce the Fokker D VII,

with a maximum speed of 192 kmph at an altitude of 7,000 m.

Most of the aircraft had limitations. The Gothas were tail-heavy. So pilots had trouble keeping the aircraft steady at landing. The lower wing of the Albatros twisted easily while the aircraft dived. All aircraft shared one danger. Often the fuel tank caught fire. Pilots didn’t have parachutes. So they could not bail out when their aircraft were hit. They faced a fiery end. Often they shot themselves before the fire got to them.

The War proved the importance of air power in war. The men who headed Britain’s War Office realised this and held meetings to debate the issue. These deliberations led to the formation of the Royal Air Force on 1 April 1918.

That marked the culmination of a small, hesitant start made in 1908. In the same year, on 16 October, the first British Army Plane, designed by Cody, flew a distance of 410 m. That was just a flash in the pan. After the flight, a cost study was undertaken. The project had cost over 2,500 pounds. That was considered too high. Further work on the aircraft was shelved and the factory shut down.

However, within a year, Britain received a new jolt. Louis Bleriot flew across the English Channel. That flight was an eye-opener for the British. For centuries, the people had looked upon the English Channel as a God-given defence, a natural moat. It had warded off attacks by sea, on several occasions in the past. Bleriot’s crossing of the Channel marked the end of the Channel’s invincibility. The Channel could not provide any defence against air attack.

Around this time came reports of progress by France and Germany in aviation. Bleriot, Deperdessin, Morane and Farman, four French companies, took the lead in the production of aircraft. Britain could buy French aircraft. But that would leave Britain dependent on the French. Self-reliance became the need of the hour.

The old factory was restarted. Geoffrey de Havilland, who had the requisite expertise, joined the factory as designer and test pilot (Fig. 4.6). He developed the two-seater biplane model B. E. 1. It was improved and developed as the B. E. 2 (Fig. 4.7).

The formation of the Royal Air Force came months before ■’ – y J d. В t, ‘ the brief span, the newly designed fighter aircraft hunted down

The formation of the Royal Air Force came months before ■’ – y J d. В t, ‘ the brief span, the newly designed fighter aircraft hunted down

enemy submarines and ships, and carried out heavy bombing of enemy installations and formations.

The War ended. The Allies won. Peace returned. Human development needed more funds. Investment in defence came in for pruning. Would it affect the progress of aviation? It could have but for the farsightedness of Winston Churchill (he later became Prime Minister of England and

led the nation to victory in the Second World War), who was the Secretary of State for both War and the Royal Air Force (RAF). He backed the RAF to the hilt, encouraged establishment of schools to train pilots. Mock fights and air stunts won public backing to the Air Force.

The pilots did not remain idle. The RAF saw action in campaigns against tribals in British colonies. It flew in to contain troubles in Iraq in 1922. In 1928, tribal groups of Afghanistan, led by Kabibullah Khan, rose in revolt. The men surrounded the British Legation at Kabul and took 586 people as captives. How could the captives be rescued? The terrain was mountainous, rugged, mostly snow-covered. Wild winds swirled around. The Royal Air Force was assigned the task of airlifting the captives. The pilots rose to the occasion. The operation was truly hazardous. The weather was unpredictable. The terrain was hostile. Yet the pilots completed the rescue, despite ceaseless gunfire from the ground.

Each successful operation gave a stimulus to research in aircraft design. Powerful engines and new designs enhanced the speed and range of aircraft. The First World War had given a big boost to aviation.

Leonardo da Vinci, the famous artist, was an innovator too. He too wanted to fly. But he was not foolhardy. He noticed that objects, heavier than air, flew for very short duration. But gravity slowed them down and forced them to the earth. He studied the design of the boomerang used by the aborigines of Australia. He read about gliders, popular in China. He watched birds in flight. Slight movement of the wing or tail helped eagles glide in space on air currents without flapping the wings. Da Vinci sat down and drew pictures of wings and tails of various birds. He designed a birdlike flying machine. Can a machine take off verticall? He tried the airscrew machine, which is the forerunner of the helicopter. He tested the design of a parachute.

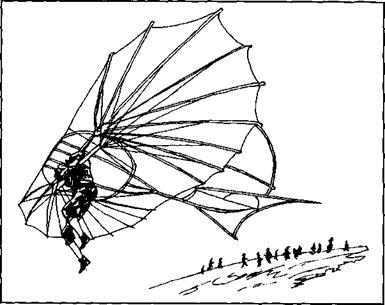

Leonardo da Vinci, the famous artist, was an innovator too. He too wanted to fly. But he was not foolhardy. He noticed that objects, heavier than air, flew for very short duration. But gravity slowed them down and forced them to the earth. He studied the design of the boomerang used by the aborigines of Australia. He read about gliders, popular in China. He watched birds in flight. Slight movement of the wing or tail helped eagles glide in space on air currents without flapping the wings. Da Vinci sat down and drew pictures of wings and tails of various birds. He designed a birdlike flying machine. Can a machine take off verticall? He tried the airscrew machine, which is the forerunner of the helicopter. He tested the design of a parachute. Sir George Cayley got a bright idea. "Success in flight would come", he said, "by making a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air" (Fig. 1.2). In 1853, he built a glider. Its wing surface was 200 square feet. It had three pair of wings and a tailpiece. The wings curved more on top than on the bottom. (This design was backed by Bernoulli’s principle. An object, with a flat base and a curved top, reduces air pressure on top. This results in upward thrust). Cayley mounted the glider on wheels. It had room for a man. Cayley’s coachman got on to the glider. The glider was pulled fast across a vast open ground. It gained the speed needed to take off.

Sir George Cayley got a bright idea. "Success in flight would come", he said, "by making a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air" (Fig. 1.2). In 1853, he built a glider. Its wing surface was 200 square feet. It had three pair of wings and a tailpiece. The wings curved more on top than on the bottom. (This design was backed by Bernoulli’s principle. An object, with a flat base and a curved top, reduces air pressure on top. This results in upward thrust). Cayley mounted the glider on wheels. It had room for a man. Cayley’s coachman got on to the glider. The glider was pulled fast across a vast open ground. It gained the speed needed to take off. William Henson hailed him ‘The Father of Aviation’. He improved the design of Cayley by adding two pusher propellers and managed a short flight. He dreamed of air travel to Egypt and beyond. That ended as a pipe dream. He moved to America and spent his life advocating further research into aviation.

William Henson hailed him ‘The Father of Aviation’. He improved the design of Cayley by adding two pusher propellers and managed a short flight. He dreamed of air travel to Egypt and beyond. That ended as a pipe dream. He moved to America and spent his life advocating further research into aviation.

The risk was worth taking, thought Louis Bleriot, of France (Fig. 3.2).. Flying was his hobby. He was a daredevil. Many were the tumbles that he took during his previous flights with kites and gliders. He had broken his skull; pulled his calf muscle; limped for a fortnight after being thrown out of a glider, as it came in to land; received hard knocks and severe bruises on several occasions.

The risk was worth taking, thought Louis Bleriot, of France (Fig. 3.2).. Flying was his hobby. He was a daredevil. Many were the tumbles that he took during his previous flights with kites and gliders. He had broken his skull; pulled his calf muscle; limped for a fortnight after being thrown out of a glider, as it came in to land; received hard knocks and severe bruises on several occasions.

He tried again. This time, he covered nearly 2 km. Sweet were the fruits of success. Curtiss savoured his victory.

He tried again. This time, he covered nearly 2 km. Sweet were the fruits of success. Curtiss savoured his victory. "This is one flight I can undertake. If only I can find a sponsor, who gets me an aircraft and also provides funds to equip it…" Alcock didn’t complete the sentence.

"This is one flight I can undertake. If only I can find a sponsor, who gets me an aircraft and also provides funds to equip it…" Alcock didn’t complete the sentence.

The roar of the engines was loud.

The roar of the engines was loud. This was just the beginning. Soon came a brilliant idea. Can’t single-seated aircraft fly over enemy territory and drop bombs? That marked the birth of bombers. New designs improved the speed and manoeuvrability and fighting power of the aircraft.

This was just the beginning. Soon came a brilliant idea. Can’t single-seated aircraft fly over enemy territory and drop bombs? That marked the birth of bombers. New designs improved the speed and manoeuvrability and fighting power of the aircraft.

The formation of the Royal Air Force came months before ■’ – y J d. В t, ‘ the brief span, the newly designed fighter aircraft hunted down

The formation of the Royal Air Force came months before ■’ – y J d. В t, ‘ the brief span, the newly designed fighter aircraft hunted down

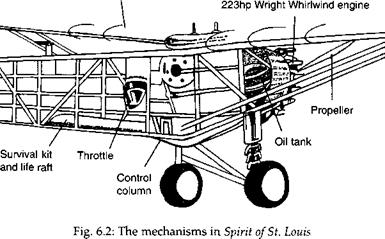

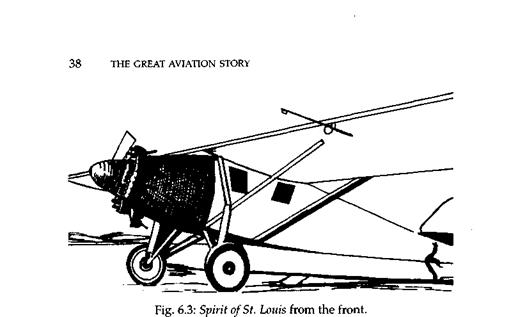

Many friends asked him why he wanted to stake his life on the risky venture. He laughed off their fears. "I’ve designed this plane. It can carry enough fuel to last me for the journey. I may have some to spare too, at the end of the journey. As regards my decision to fly solo, well, I’d be better off with more asoline than an extra man", said Lindbergh.

Many friends asked him why he wanted to stake his life on the risky venture. He laughed off their fears. "I’ve designed this plane. It can carry enough fuel to last me for the journey. I may have some to spare too, at the end of the journey. As regards my decision to fly solo, well, I’d be better off with more asoline than an extra man", said Lindbergh.

On 27 June 1928, The Friendship set out on the historic flight from Trepassey Bay, New Foundland. The plane ran in and out of fog and clouds, storms and cold icy winds. The radio didn’t function properly. One of the engines caused problems. The pilots got a scare when the fuel gauge indicated that the plane would remain airborne only for a couple of hours more. But luck favoured them. They touched down at Burry Port, in South Wales, England. They had covered 3420 km in 24 hours

On 27 June 1928, The Friendship set out on the historic flight from Trepassey Bay, New Foundland. The plane ran in and out of fog and clouds, storms and cold icy winds. The radio didn’t function properly. One of the engines caused problems. The pilots got a scare when the fuel gauge indicated that the plane would remain airborne only for a couple of hours more. But luck favoured them. They touched down at Burry Port, in South Wales, England. They had covered 3420 km in 24 hours

Every time a barrier is broken, a new challenge comes into focus. This time, the challenge revolved around the question, "Can anyone fly an aircraft non-stop around the world?"

Every time a barrier is broken, a new challenge comes into focus. This time, the challenge revolved around the question, "Can anyone fly an aircraft non-stop around the world?"