DARE DEVILS

Courage conquers, we said. Every pioneer displays courage of a high order. Each one is a dare devil. Each feat is unique. A quick survey of the history of aviation leads us to more names and events. Let us take note of some of the men and events that made aviation history.

The first name that comes to mind is of Sir George Cayley. He tracked down the forces that needed to be controlled before one could fly. These were Tift, drag, thrust and gravity’. He developed the controlling mechanisms to counter-balance these forces and thus provide balance to the flying object. He shaped the horizontal rudder (or elevator), experimented with multiple-wing designs, thought of the propeller. For over forty years, he worked. Finally, in 1849, he decided to test fly his tri-plane glider. He strapped a 10- year-old boy on to the glider and tested it at the open grounds close to his home Brompton Hall. The glider soared in space.

The first name that comes to mind is of Sir George Cayley. He tracked down the forces that needed to be controlled before one could fly. These were Tift, drag, thrust and gravity’. He developed the controlling mechanisms to counter-balance these forces and thus provide balance to the flying object. He shaped the horizontal rudder (or elevator), experimented with multiple-wing designs, thought of the propeller. For over forty years, he worked. Finally, in 1849, he decided to test fly his tri-plane glider. He strapped a 10- year-old boy on to the glider and tested it at the open grounds close to his home Brompton Hall. The glider soared in space.

Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic solo and created an endurance record. The round the world trip in The Voyager by Dick and Jeana set another endurance record. Charles Kingsford Smith tried a different type pig 13 1; Charles of endurance (Fig. 13.1). He became Kingsford Smith

|

Fig. 13.2: The record-breaking flight round Australia |

the first man to fly across the Pacific. He set out, with three others, in May 1928, from Oakland Airfield, US, and landed at Brisbane in June (Fig. 13.2). For him it was a dream come true.

Amelia Earhart was not the first woman aeronaut. That glory belongs to Jeanne-Genevieve Garnerin who soared in space in a balloon. She also was the first parachutist. Mrs. Cromwell Dixon was amused when her 13-year-old son invited her to fly an ‘air bicycle’. He told her that she had only to pedal with all the power at her command and she would be taken into flight. She tried that in 1909. She pedalled hard and the machine took to flight, carrying her along. Therese Peltier, a French sculptor, was the first woman to fly an aircraft solo. Raymonde de Laroach was the first licensed pilot. She received the licence in 1910. Eighteen years later, Lady Mary Heath flew an aircraft from Cape Town to London. In 1932, Maruyse Bastie of France flew alone, remained airborne for 38 hours and created a record.

Flight opened up immense opportunities for the adventure seekers.

In 1911, the first major long-distance air race was organised. The route was Paris-Belgium-Holland-England (over the Channel) and back to Paris. There were 43 entries; and 12 different types of aircraft. Nineteen participants completed the first lap. Nine crossed the finish line. Three lost their lives and six were seriously injured. The races, held annually, drew a lot of enthusiastic participants.

In 1913, the Michelin Cup Race set down a challenge for pilots. They were required to cover specific distance and maintain an average speed of 50 kmph. At the Gordon Bennett Trophy, held in the same year, Jules Vedrines’ aircraft recorded a speed of over 160 kmph. It took another seven years to double this speed record. Flying a 300 hp engine, Sach Lecointe registered, at Etampes, speed of over 320 kmph. In 1922, Billy Mitchell broke this record and won the Pulitzer race with a speed of 350 kmph. The quest for speed finally led man to the Concorde (Fig. 13.3). In 1995, the Concorde flew round the globe, taking short halts at Touclouse in Southern France, Dubai, Bangkok, Guam, Honolulu and Acapulco in Mexico before returning to New York, in less than 33 hours.

The quest for more speed demanded improved designs. Often the newly designed aircraft crashed. Accidents took a heavy toll of men and material. But mishaps did not deter the daring. Many young men explored the limits to which the aircraft would go along with them. They performed loops and turns, dipped and rose. Large crowds gathered to watch stunt shows.

Charles Willard, a Harvard graduate, trained under the ace flier and aircraft designer, Curtiss, before he turned to stunt shows. He came to be known as the Wizard. In 1910, he commanded $1,000 per flight. Many others took to stunt shows. But most of them died in accidents. A common say-

|

Fig. 13.3: The Concorde |

ing, in those days, read: "There are plenty of bold flyers; and plenty of old flyers, but hardly any bold old flyers".

In 1913, at a public show, Edouard Pegoud performed death-defying loops in space. The aircraft gracefully arched and turned around, yielding to the command of the pilot. The Press reported the show.

Lincoln Beachey, who revelled in performing spirals and dives with planes, read the news. He decided to try the stunts. He set before Curtiss his plan. He wanted a specially reinforced bi-plane that could stand the strain of sharp loops. The first model crashed. The second one stood the trials. It had a top speed of over 165 kmph. Lincoln Beachey scheduled his show for 14 March 1915. He took off from San Francisco, climbed over the bay toward Alcatraz, reversed course and performed a series of loops, losing height with each one. Back he climbed to 1100 m and dived straight down.

He dropped so low that people could spot his head above the wings. It looked as if he was crashing. But, at the very last moment, he pulled sharply on the stick to regain level flight. That was too much for the aircraft. The wings broke away. The aircraft crashed in the bay. The stuntman was alive, but was trapped in the wreckage. He drowned before he could be pulled out.

After the end of the Second World War, many young fighter pilots were jobless. The more daring among them found work as stunt pilots. They showed their skill at carnivals. They walked on the wings, while the plane was in flight, or jumped from plane to plane while in flight or got on to aircraft from running cars, ambling up rope ladders suspended from jennies.

In September 1999, Jurgis Kairys, a Lithuanian pilot, displayed a rare stunt. He flew an SU-26 plane at a speed of about 300 kmph under 10 bridges spanning the Neris River at Vilnius, the capital of the Baltic State. It was a risky show. The bridges are just 6 m above the waters. That did not deter Jurgis. It took him just under 20 minutes to complete the show. Asked what more he had in mind, Jurgis joked, "The only thing that remains to be done is to fly under all the bridges upside down". Speaking about this show, Jean Louis Monnet, Chief Executive of the International Air Sport Federation, said: "As far as I know, this was the first stunt like this in the world".

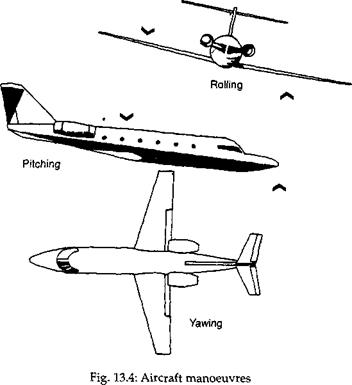

In India, the Air Force often organises special air shows. On Republic Day, the aircraft perform stunts over Raj Path. They loop around, fall freely through space, swiftly turn, regain height and vanish into the sky. The aircraft fly in formation, yet not once do they get into the flight path of each other (Fig. 13.4).

A different form of challenge came in with the arrival of ultralight crafts. In 1960, Francis Rogalli developed a lightweight plastic arrowhead shaped flexible wing. He called it

|

|

para-sail. It was meant to be a gliding type of parachute for lowering pieces of cargo from high-flying aircraft. It did not find favour with the defence agencies. Acceptance came from an unexpected quarter. Gliding experts picked it up. They rigged a sort of trapeze, spread fabric to form the wing and added a few wires to control flight by shifting weight on trapeze. Thus began the sport of hang gliding. In the mid 1970s, they added small engine and propeller to the craft.

The glider has no wheels, no landing gear. The man riding the glider runs into the wind and takes off. Often the lover of gliding takes the glider to the top of a slope and runs down picking up speed till the glider gets airborne.

Himachal Pradesh holds annual hang gliding competitions before winter really sets in. Hang gliding has become very popular world over.

Is there any room for heady excitement, while we stay on the ground? Radio controlled sailplanes provide this facility. These parasails are very light. Hardly 2 kg, including the radio, placed in a little black box in the nose of the plane! The person on the ground operates the control and defines the flight path.

People who fly the machines, be it an aircraft or helicopter or glider or parasail, constantly improve designs to break established speed or endurance records. They believe that when it comes to development, even the sky doesn’t set limits.