Final Preparations

With most preparations for President Nixon’s involvement with Apollo 11 in place, Frank Borman in early July made a quick visit to the Soviet Union. He had met Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin in January, and Dobrynin had followed that meeting with an invitation for Borman and his family to visit Moscow. Borman informed Nixon and his national security adviser Kissinger of the invitation, and they urged him to accept. Borman remembers that Nixon “was already intrigued” with the idea of U. S.-U. S.S. R. cooperation in a joint space mission, and he viewed the Borman visit as an “opening wedge” in the process of defining such a mission. Borman was the first U. S. astronaut to visit the Soviet Union, and his trip received positive press coverage there. In a formal meeting with the president of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, Mstislav Keldysh, who was the senior publicly acknowledged official in the Soviet space program, Borman raised the possibility of the United States and the Soviet Union increasing their space cooperation, and got a positive response. On his return to the White House, Borman reported to the president that he had not “gathered much technical information on the Soviets’ space program,” but had gotten the impression that “the Soviets would be receptive to a joint space mission.” The July 1969 Borman visit can thus be seen as a first step leading to the 1975 joint U. S.-Soviet Apollo-Soyuz mission with its “handshake in space.”21

The good relations created by Borman on his trip had an immediate payoff. On July 13, three days before the Apollo launch, the Soviet Union launched the Luna-15 robotic probe, with the intent of first orbiting, then landing on, the Moon, scooping up some lunar soil, and bringing it back to Earth. There was some concern that the trajectory of the Soviet mission might intersect with Apollo 11 while both were in lunar orbit, resulting in a collision. At NASA’s request, Borman used the White House-Kremlin “hot line” to send a message to Keldysh requesting the orbital parameters of the Soviet probe. On July 17, Keldysh replied with the requested information, saying that “the orbit of probe Luna-15 does not intersect the trajectory of Apollo-11 spacecraft.” Never before had the Soviet Union provided such detailed information on one of its ongoing space missions. While Luna-15 did reach lunar orbit, it crashed onto the Moon on July 21 as the Apollo 11 crew was preparing to lift off of the lunar surface.22

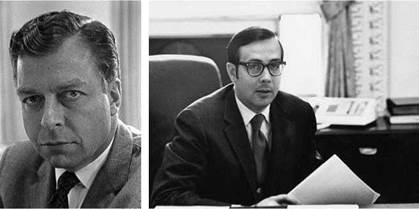

By July 14, Borman was back from his trip to the Soviet Union; he would stay involved with President Nixon until the Apollo 11 astronauts were safely back on Earth on July 24. One action Borman took at the president’s request was to prepare brief profiles of the Apollo 11 crew for Nixon and similar profiles of the crew’s wives for Mrs. Nixon. With respect to Neil Armstrong, Borman told Nixon that the mission commander was a “quiet, perceptive, thoroughly decent man, whose interests still turn to flying,” and that he “follows the stock market actively.” Armstrong was “a little reserved, but when you get to know him, he has a very warm personality.” Buzz Aldrin was described as “very athletic, aggressive, hard charging,” an “almost humorless, serious personality,” and “very concerned about social problems.” Michael Collins was in “superb physical condition.” Collins was “in some sense skeptical, more inclined toward the arts and literature rather than engineering” and a “devoted family man.” With respect to the astronauts’ wives, Borman described Jan Armstrong as “quite composed and very factual.” Joan Aldrin was “more demonstrative than either of the other wives, and perhaps more apt to show her concern.” Pat Collins “tends toward the intellectual; [is] very interested in current events”; and “enjoys evenings that include candlelight and wine for dinner.”23

NASA had sent to the White House proposed remarks for President Nixon to use as he spoke with the astronauts on the Moon. From Borman’s perspective, “the gist of those remarks was that the current administration was responsible for Apollo 11’s success. . . The statement was pure politics, an exercise in self-congratulations.” Borman advised Nixon not to use NASA’s input. He told the president “look, Mr. President, you really don’t have anything to do with Apollo 11. You’re just the fortunate or unfortunate recipient of this mission. . . If it fails, you’ll get tarred with it, and if it succeeds you’ll get some of the credit. But for you to say what NASA is suggesting—that in effect you were the father of the space program—is just plain wrong.” Rather, suggested Borman, the president should say “something very simple and nonpartisan, a few words of congratulations, and then get off the air.” Borman also advised against the plan of playing the national anthem as Armstrong and Aldrin stood next to the American flag during the telecast conversation involving the president. This “would force the crew to stand at attention for some two and one-half minutes. This time, plus the time allocated to unveiling the plaque and mounting the flag, would add up to a significant portion of the time on the lunar surface which is non-productive from a scientific or exploration viewpoint.”24

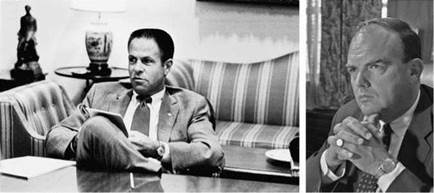

President Nixon met with Haldeman, Flanigan, Chapin, and Borman on July 14 to discuss plans for his involvement. According to Haldeman, Nixon “was really intrigued with his participation in the whole thing.” The plan at this point was for the president to go to either the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston or the Kennedy Space Center in Florida for his phone call to the astronauts on the Moon; Nixon’s long-time personal secretary Rose Mary Woods suggested that the call should instead come from the Oval Office, and the president agreed. Going into the meeting, Nixon was “cranked up” about playing the Star-Spangled Banner when the American flag was placed on the Moon, but he accepted Borman’s reservations about that idea, also recognizing “possible adverse reaction to overnationalism.”25

One more important detail had to be attended to in the final days before the launch: what to do in case of a mission failure involving astronaut deaths, particularly if Armstrong and Aldrin could not lift off the Moon to rendezvous with Michael Collins in lunar orbit. NASA had prepared a disaster contingency plan and sent it to the White House. In addition, Flanigan’s assistant Jonathan Rose reviewed with Borman and Safire a “rain plan” in the event of an Apollo H disaster, suggesting the need for a presidential statement and phone calls to the crew’s widows, and then a “National Day of Mourning” after the president returned from his around- the-world trip. Borman had earlier urged the president’s speechwriters to think about “what to say to the widows,” and Safire had prepared a statement in the event that Armstrong and Aldrin were stranded on the Moon. The suggested remarks began by saying: “Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace. These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice.” The message added: “Others will follow, and surely will find their way home.” After the president’s statement, at the point when NASA cut off communications with the astronauts, “a clergyman should adopt the same procedure as a burial at sea, commending their souls to the ‘deepest of the deep.’”26 Fortunately, this statement was not needed.