Working with the White House

In the aftermath of the OMB director’s review on October 22, George Low focused his attention on making NASA’s case to OMB, the Flax committee, and the science adviser’s office, while Fletcher was working to gain the support of those at the policy and political levels at the White House. Having observed Low’s actions from outside NASA, Klaus Heiss would later comment that “George Low was the key creative figure. . . when crucial decisions came, they were George Low’s decisions. . . He had enough engineering and other judgment that people respected him. . . He was crucial to NASA at that time.”24

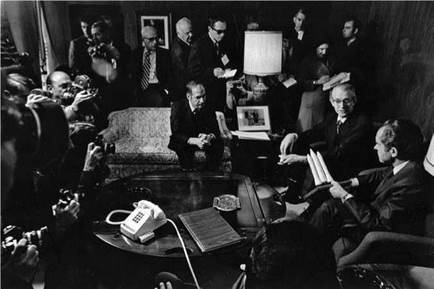

Fletcher lunched with Whitehead and Anders on November 5 “to discuss how NASA could better relate to OMB and the White House staff.” Whitehead felt that “there are only two ways to bring together the diverging views of the White House staff.” One was “to let Peter [Flanigan] act as our [NASA’s] advocate in White House circles and, in particular, with the President. To do this we would have to keep Peter better informed.” A second option was “to call the essential constituents together and thrash through what we felt is a program responsive to the President’s desires (which, incidentally, coincide with the national interest).” If this were done, “when the time came for a battle with OMB or to confront the President with alternatives, there might be a reasonable degree of support from the White House staff.” Whitehead thought that “at the present time Henry [Kissinger] is very much an advocate of space, but more particularly the Manned Space Program; that Peter and Ed [David] were neutral; and that OMB, as possibly represented by George Shultz, is in favor of a continued reduction, year by year, in NASA’s total budget.” Whitehead believed that “these views need to be reconciled in favor of an agreed upon national program which makes sense.”25

In mid-November, Anders gave Low a rundown of the positions on the space shuttle of key White House players:

Weinberger: is a real space buff. The only one in OMB really positive toward the NASA program. Causes Rice to over-balance in the opposite direction. Everybody lower in OMB is negative.

Rice: the most knowledgeable opposition comes from Rice. Feels that NASA is out of control; however, he will probably support a glider on a TITAN III.

Ed David: . . . noticeably quiet, measuring his words, and repeatedly saying he represented science and that other factors are involved. . . Not really plugged into the President.

Flax: Fubini is really running the Flax Committee. Flax apparently states that no program as large as the Shuttle will gain continuing support. We need a less costly program. . . Flax is driving David toward the glider and not vice versa. . . David will support the Orbiter with the parallel staged pressure fed booster [the TAOS concept] if Flax so recommends.

Whitehead: Whitehead could be helpful in making Flanigan a meaningful communication link to the President. . . Whitehead’s main motivation now is to improve the Fletcher/Flanigan communications link. Whitehead can be extremely helpful in selling the NASA desired Shuttle approach. . . Believes in a $3.5 billion NASA.

Rose: [Jonathan Rose was Whitehead’s replacement as Peter Flanigan’s assistant tracking space issues] is the California unemployment buff in the White House. Tries to be helpful and sees Flanigan all the time. He defers to Whitehead when Whitehead is present.

Flanigan: states that the Shuttle story is improving; however, he is by no means convinced that there should be a Shuttle. Is strongly influenced by Whitehead, Rose, and David.

Peterson: [Peter Peterson was White House international economic counselor] is the most negative of all about NASA. Perhaps the most dangerous opposition we have within the White House. Believes that the space program is the place to take money to stimulate technology. Asked why not take $1 billion out of space and who needs manned space flight.

Ehrliehman: asked the question, “Given the public attitude on space, why not put money in aeronautics?” However, he is very much concerned about the aerospace industry and will probably go along with whatever OMB/OST/ Flanigan recommend.26