Tier One

Burt Rutan does not release much information about a newest aircraft while it’s under development. In fact, it is usually not until the aircraft is ready to fly that people finally get a glimpse of his newest project. The in-house name of their secret space program was Tier One. This name wasn’t uncommon to Scaled Composites. Rutan used “tier one,” “tier two,” and “tier three” to designate what he described as the “fun factor” of a program. When tier-one programs came around, the company would always bid on them, since they were highly motivational programs for his employees, which helped him retain his skilled staff while being out in the middle of a great big desert. Scaled Composites normally used the aircraft’s name as the in-house program name. But this program of course had two vehicles.

“I was making a point to my employees that this was going to be the most fun program that we’ve ever done and the most important one for us to do,” Rutan said.

“That was the original reason behind calling the SpaceShipOne program Tier One. Later on when we started to entertain if we should do other manned spacecraft, I just had a feeling that I should make a category for different basic areas of manned spacecraft. Because it seemed like a good breakdown, I defined that if we do programs in the future that send people to Earth orbit, it would be called Tier Two. If we do things that send people outside of Earth orbit to other heavenly bodies like the Moon and Mars, it would be called Tier Three.”

The spacecraft and the carrier aircraft needed names, too. The spacecraft was Rutan’s Model 316, and the carrier aircraft was Model 318. “Those I assign when I first look at the requirements and

have the first idea of what would be the configuration solution. Those model numbers were assigned years before we had a funded program for building.”

|

|

Г

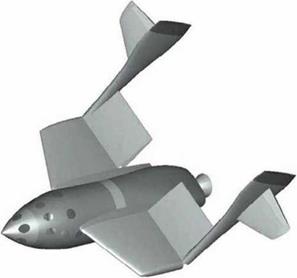

Fig. 1.11. The feather mechanism, the most innovative feature of SpaceShipOne, allowed the rear half of the wings and the tail booms to fold upward, which prevented dangerous heat buildup upon reentry but enabled a very stable descent. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, provided courtesy of Scaled Composites

к_____________________________ )

![]() г

г

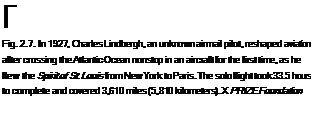

Fig. 1.12. Since wind-tunnel testing was not part of the design and development of SpaceShipOne because of the large expense, Scaled Composites used a computer method called computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to model the aerodynamics. The photograph shows designer Burt Rutan and aerodynamicist Jim Tighe reviewing a computer analysis of SpaceShipOne. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by Scaled Composites

к_____________________________ ;

![]()

SpaceShipTwo and its launch aircraft are Models 339 and 348, respectively.

Rutan added, “We’ve only flown thirty-nine manned airplanes. Most of the concepts don’t get funded and developed.”

One example of this is Model 317. This was the design that squeaked between theTier One spacecraft and its mothership. A new – concept vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) light aircraft, the tail-sitter would take off like a helicopter but fly conventionally.

White Knight was named by Cory Bird, an employee of Scaled Composites who also flew as a flight engineer in the carrier aircraft on several of the test flights. Bird had made a drawing of a knight in white armor, which Rutan thought was very clever. The drawing ended up being the insignia for White Knight, too.

And although Rutan names very few of his airplanes, the spacecraft was an exception. “I wanted to make a point that other manned systems that carried people into space tended to be capsules or spacecraft. But if you read fantasy that kids do, it’s always a spaceship. And I thought this is interesting in that there has been a lot of manned spacecraft, capsules, and vehicles, and all these boring names. I felt that this might be the first thing that flies people into space, that you have the moxie to call it a spaceship.”

So, since he considered it the first spaceship, he mixed the words around with numbers. “And I thought, I don’t have any problem

Ґ ‘ Л

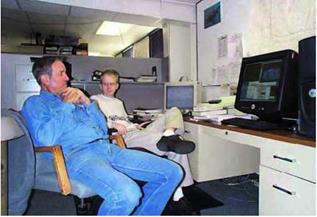

Fig. 1.13. By using computer analysis, Scaled Composites was able to evaluate the aerodynamic characteristics of SpaceShipOne even before construction got started. However, it was still necessary to test SpaceShipOne in flight to get the complete picture. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, provided courtesy of Scaled Composites

V_____________________________ ) calling this SpaceShipOne because I want to build a SpaceShipTwo, and I want to build a SpaceShipThree.”

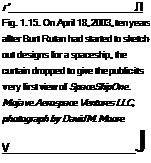

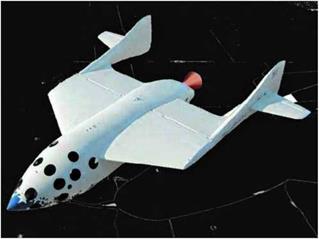

Figure 1.14 shows SpaceShipOne mated up to White Knight before the public unveiling and even before paint schemes were added.

In order to be able to fly, though, SpaceShipOne and White Knight each needed a tail number, which is unique identification that every aircraft has similar to a car’s license plate, and had to be registered with the FA A. SpaceShipOne was given N328KF, which stood for

328,0 feet, the boundary line between Earth’s atmosphere and space, while White Knight was given N318SL, where the 318 model number and the SL stood for spaceship launcher.

“We didn’t get our first choices on that,” Rutan said. “For example, I wasn’t particularly enamored by 328KF. I would have rather had 100KM, 100 kilometers. But it was taken.”

Along with the tail number, the type of aircraft had to be identified to the FA A. White Knight was pretty straightforward, but SpaceShipOne wasn’t so clear cut. The FA A felt that commercial launch licensing was required for SpaceShipOne. This was a somewhat long and drawn-out process. So as not to delay flight testing, Scaled Composites initially registered SpaceShipOne as a glider. This made perfect sense because about half the time during a spaceflight SpaceShipOne was a glider. But more importantly, the initial flight testing would be done without a rocket engine. So, by calling it a glider first, Scaled Composites was able to buy some time before having to get their commercial launch license, even though Rutan had no intention of using SpaceShipOne commercially.

“When I was out in Mojave for the first-time flight of the X Prize that Mike Melvill flew, it was the first time I had a chance to spend some time with Burt’s design team,” Poberezny said. “And what was striking was the intelligence that he recruited, the youth and the motivation. In other words, they were hungry and they were motivated to be successful and to make a difference. So, I give Burt a lot of credit. When he saw talent, he brought them in.”

г

г

Fig. 1.14. Shown before their paint schemes were added, SpaceShipOne and White Knight share virtually identical cockpits and instruments. But where White Knight has jet-engine controls, SpaceShipOne has rocket-engine controls. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by Scaled Composites

к______________________________________

Rutan gave direction and vision to his staff but still allowed them to exercise their own strengths and abilities. And Rutan would depend on the contributions of the entire team at Scaled Composites to get SpaceShipOne into space.

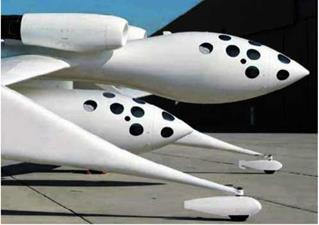

On April 18, 2003, slightly more than two years after receiving Paul Allen’s backing, Rutan was ready to go public. SpaceShipOne could no longer be hidden away in Scaled Composites’ hangar. All the components ofTier One were in place, and SpaceShipOne was ready for flight testing. Figure 1.15 shows SpaceShipOne after the curtain dropped.

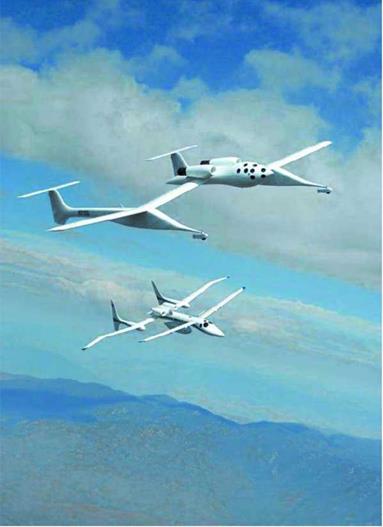

White Knight had been flying since August 2002. It was strange enough looking, yet similar enough to the way-out look of Proteus that Scaled Composites didn’t worry too much about it occasionally being spotted ahead of time. Both these aircraft have been widely described as looking like giant prehistoric insects or spaceships from Star Trek.

It would be a full month, though, before SpaceShipOne would take to the air for the first time. However, Rutan had a surprise in store for his guests at the coming-out party. He had White Knight do fly-bys for everyone gathered at the flightline in front of the Scaled Composites hangar. Figure 1.16 shows Proteus, the original spaceship launcher, and White Knight, the new spaceship launcher, flying together, and table 1.1 gives the specifications for White Knight.

Aside from the two vehicles, the other important Tier One components were revealed, refer to figure 1.17.The test stand trailer (TST) was a partial mockup of SpaceShipOne used to develop the rocket engine. A tanker truck called the mobile nitrous oxide delivery system (MONODS) supplied the nitrous oxide (N20) to the oxidizer tank on the TST and in SpaceShipOne. And the Scaled Composites unit mobile (SCUM) truck was used for ground control, providing

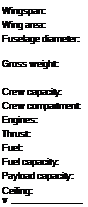

Table 1.1 White Knight Specifications 82 feet (25 meters)

468 square feet (43.5 square meters)

60 inches (152 centimeters) for maximum outer diameter

19.0 pounds (8,620 kilograms) at takeoff with SpaceShipOne

one pilot (front seat) and two passengers (back seat) "short-sleeved" pressurized cabin two J-85-GE-5 turbojets with afterburners 7,700 pounds-force (34,000 newtons)

JP-1

6,400 pounds (2,900 kilograms)

8,000-9,000 pounds (3,630-4,080 kilograms)

53.0 feet (16,150 meters)

|

_____________________ J

|

г

Fig. 1.16. Proteus, flying below White Knight, first took flight in 1998 and was originally planned as the carrier aircraft for a single-person rocket. As the spacecraft design evolved into SpaceShipOne, the larger White Knight was required. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by Scaled Composites

к________________

a telemetry link with the TST during rocket-engine testing or SpaceShipOne during a flight.

The last component, shown in figure 1.18, was the flight simulator, which Scaled Composites specially designed for Tier One. It was the first flight simulator Scaled Composites ever built and used for one of their aircraft.

Having a sponsor instead of a customer, building with a robust design approach, performing incremental testing, incorporating as many similarities between SpaceShipOne and White Knight as possible, and conducting extensive pilot training in the flight simulator, White Knight, and Extra 300 aerobatic plane would all prove key factors upon which the success of Tier One would depend.

Г ^

Fig. 1.17. Tier One, the space program of Scaled Composites, comprised SpaceShipOne, the spacecraft; White Knight, the carrier aircraft; test stand trailer (TST), the rocket-engine testing platform; mobile nitrous oxide delivery system (MONODS), the nitrous oxide (N20) supply tanker; and Scaled Composites unit mobile (SCUM) truck, a ground-control station. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by Scaled Composites

V____________________________ )

|

|

Г Л

Fig. 1.18. Jeff Johnson, project manager for Mojave Aerospace Ventures, sits at the simulator control desk and monitors the progress of a simulation. One of the most critical components of Tier One was the flight-training simulator. Primarily designed by Pete Siebold, it allowed the test pilots to practice and refine the techniques required to fly the challenging trajectory of SpaceShipOne. Mojave Aerospace Ventures LLC, photograph by David M. Moore

V________________ J

On November 22, 2001, Steve Bennett’s Starchaser team, based in the United Kingdom, became the first competitor to launch a vehicle while displaying an X Prize logo. The single-person Nova capsule, unmanned at the time, rode atop the Starchaser 4 booster. The rocket reached a height of 5,541 feet (1,689 meters). Courtesy of Starchaser Industries

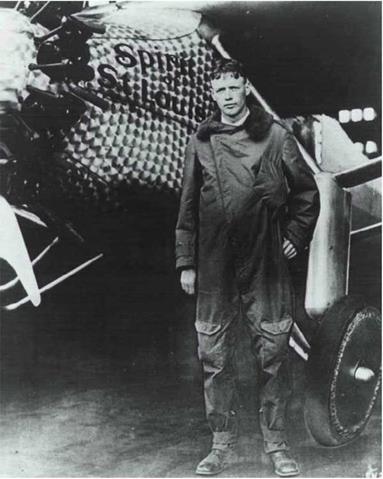

Fig. 4.3. Parked in front of the B-29 mothership, the X-1 was built by Bell Aircraft Corporation for the U. S. Army Air Forces and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the predecessors of the U. S. Air Force and NASA, respectively. The X-1 ‘s revolutionary use of structures and pioneering aerodynamic shapes and controls enabled Chuck Yeager to become the first to break the sound barrier, flying faster than Mach 1. NASA-Dryden Flight Research Center

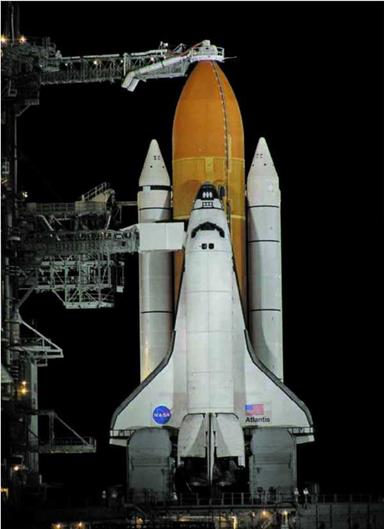

Fig. 4.3. Parked in front of the B-29 mothership, the X-1 was built by Bell Aircraft Corporation for the U. S. Army Air Forces and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the predecessors of the U. S. Air Force and NASA, respectively. The X-1 ‘s revolutionary use of structures and pioneering aerodynamic shapes and controls enabled Chuck Yeager to become the first to break the sound barrier, flying faster than Mach 1. NASA-Dryden Flight Research Center Fig. 4.4. Known as lifting bodies because they were considered wingless, the rocket-powered X-24A, M2-F3, and HL-10 (left to right) dropped from a B-52 to explore the possibility of returning from space in an unpowered glide. Up until then, spacecraft had only returned from space using parachutes, and the data obtained by these vehicles helped pave the way for the Space Shuttle. NASA-Dryden Flight Research Center

Fig. 4.4. Known as lifting bodies because they were considered wingless, the rocket-powered X-24A, M2-F3, and HL-10 (left to right) dropped from a B-52 to explore the possibility of returning from space in an unpowered glide. Up until then, spacecraft had only returned from space using parachutes, and the data obtained by these vehicles helped pave the way for the Space Shuttle. NASA-Dryden Flight Research Center

f ^

f ^ г———————————————————-

г———————————————————-