Decentering the Object in Technoscience

The list of persons and organizations who have contributed to this work is too long to include in full. But I would particularly like to mention and thank the following: British Aerospace plc and Rolls Royce plc offered access to material relevant to the TSR2. I am deeply grateful to them for their generous help and assistance without which it would have been impossible to write the present book. This support has come in many forms over a number of years, and has gone far beyond the routine. Accordingly, I thank both organizations for their systematic support and assistance while noting that what I have written is my own responsibility, and does not necessarily reflect the views of either company.

It is also my particular pleasure to thank the Brooklands Museum at Weybridge, Surrey, British Aerospace North West Heritage Group at Warton, Lancashire, and the Rolls Royce Heritage Trust at Filton, Avon. These are organizations, largely staffed by volunteers, that are responsible for collecting and collating the historical records of the two companies. Their work is indispensable to any student of the history of aviation in the United Kingdom and has been crucial in many ways to the present study. I am deeply grateful to them and in particular to the many individuals who, in serving the historical record in this way, have also generously facilitated the study and helped to ease my way at every turn.

I would also like to thank the numerous employees of British Aerospace and Rolls Royce plc and their predecessor companies, and a number of related companies with whom I corresponded. In many cases these people also agreed to be interviewed, and I am particularly grateful to them for generously giving up their time to delve into a project that left distressing memories for many. The same is also true for the politicians, civil servants, and Royal Air Force officers who also unsparingly gave of their time. Since some of them prefer to remain anonymous, I will not here mention any of these kind people by name. In many cases, however, they offered crucial insights into the TSR2 project, the character of military procurement, the nature of defense thinking, and the management of large technological projects.

I am most grateful to the Nuffield Foundation, Keele University, and the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Mines de Paris for financial, material, and practical support for the research. The Nuffield Foundation generously offered grant aid to support the original research.

Keele University kindly offered sabbatical and other research leave that made it possible to undertake a sustained period of writing. The Ecole Nationale Superieure des Mines de Paris, and in particular the Centre de Sociologie, offered material support and encouragement throughout. And the Sociology Program of the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University offered fellowship support that provided the blessed respite from the usual commitments that enabled me to complete the manuscript. The research and this book would most certainly not have been completed without the assistance of these four institutions.

I am very grateful to participants in a number of seminars where I was invited to present earlier versions of parts of this text. These seminars took place at Wetenschaps en Technologiedynamica of the Universiteit van Amsterdam, the Netherlands, CRICT at Brunel University, UK, the Department of Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, UK, the Department of Sociology at Copenhagen University, Denmark, le Centre de Sociologie de l’Innovation at the Ecole Nationale Superieure des Mines de Paris, France, the Centre for Social Theory and Technology at Keele University, UK, the Department of Sociology at Lancaster University, UK, Tema T at Linkoping University, Sweden, the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at Melbourne University, Australia, and the Area de Innovacao Tecnologica Organizacao Industrial (ITOI), Programa de Engenharia de Producao, COPPE, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. The encouragement, support, and critical comments offered at these seminars have been vital to the process of thinking through the arguments that I make here—though I remain conscious of the fact that I have not succeeded in responding to many of the important points raised.

I am deeply grateful to many friends and scholars who have helped, in some cases unknowingly, but more often in the course of extensive and generous discussion, to create the intellectual and political space that has led to this book. I would like in particular to mention Madeleine Akrich; Malcolm Ashmore; RuthBenschop; OlafBoettger; Brita Brenna; Michel Callon; Claudia Castaneda; Bob Cooper; Anni Dugdale; Mark Elam; Martin Gibbs; Donna Haraway; Antoine Hen – nion; Kevin Hetherington; Karin Knorr-Cetina; Bruno Latour; Nick viii Acknowledgments Lee; Celia Lury; Mike Lynch; Ivan da Costa Marques; Maureen Mc-

Neil; Cecile Meadel; Ingunn Moser; Bernike Pasveer; Peter Peters; Andy Pickering; Vololona Rabeharisoa; Paul Rabinow; Vicky Singleton; Leigh Star; John Staudenmaier sj; Marilyn Strathern; Sharon Tra – week; David Turnbull; Helen Verran; Steve Woolgar; Brian Wynne; and two anonymous readers for Duke University Press.

To all of these friends and colleagues I am deeply grateful in more ways than can be told. Many of them have been close intellectual friends for many years—and without them the book would never have been written. I would, however, particularly like to mention two people in this list. I am profoundly grateful first to Michel Callon for his many years of acute intellectual friendship, encouragement, and support, and for his conviction that the book is about distribution; and second, to Annemarie Mol for her strong intellectual friendship, the collaborative work that has gone into earlier versions of this book, and her conviction that knowing maybe performed as partially connected ontology. I thank them both.

As I write these lines I realize that all these friends share a common indifference to the bounds of disciplinary knowledge and a willingness to take inter – or nondisciplinary intellectual risks. Such risks seem at least as great in the current climate of unremitting academic audit as they ever have in the past, and I am all the more grateful to them for resisting regional restrictions to the character of intellectual inquiry.

Finally I would like to thank Sheila Halsall, Duncan Law, and Angus Law who have lived with and contributed to this book in one form or another for more than ten years.

A version of chapter 6 has been published in Configurations, vol. 8, no. 1 (winter 2000). I am grateful to the publisher for allowing it to be included in this volume.

A plateau is always in the middle, not at the beginning or the end. A rhizome 1

is made of plateaus.—Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus:

Capitalism and Schizophrenia

Capitalism and Schizophrenia

No doubt Deleuze and Guattari have got the right idea. Matters grow from the middle, and from many places. But one also has to start somewhere.

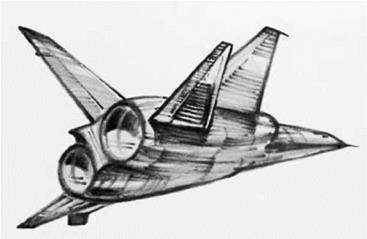

With the aircraft? This is a book aboutspecific episodes in a British attempt to build a military aircraft, a tactical strike and reconnaissance warplane, called the TSR2. The project to build this aircraft started in the 1950s and ended in 1965 when it was canceled by a newly elected Labour government. In one way or another, all the stories in this book have to do with the TSR2.

But the aircraft is not the only possible place to start. For though all the stories in this book are indeed about the TSR2, the book is really about something much more general. It is about modernism and its child, postmodernism — and about how we might think past the limits that these set to our ways of thinking. For the book is about a world, the contemporary Euro-American world, in which many have lost their faith in big theories or ‘‘grand narratives,” as Jean-Frangois Lyotard calls them (1984b). And, at least to some extent, it is about a world in which many have also lost confidence in the grand projects and plans that tend to go with those grand narratives. Nuclear power, medical practices, food safety, the environment, everywhere, or so the story runs, experts are doubted, and people are skeptical of the claims made by authorities. Including academic authorities.

Of course there are various ways of responding to this. One can wave aside the skepticism of postmodernism and insist that experts— including academic experts—still know best: that it is, indeed, possible to tell grand narratives. One can, in short, remain a modernist. Alternatively, one can insist that expert knowledges are limited in scope, but then go on to say that it is still possible to tell consistent stories so long as one understands that these have only a limited validity and that they will in due course require revision. No doubt this is the dominant response in many of the social sciences, for instance underpinning the theory of reflexive modernity.1 It is a response that says warrantable knowledge is still possible so long as

it is suitably set about with health warnings and it is not used after its sell-by date.

But there is another possibility that I want to explore in this book. This is to take the skepticism of the so-called postmodern condition seriously, which means accepting that ‘‘modernism’’ is flawed even in its more supple versions. It is to accept that modernism never achieved the smoothnesses it sought, that its foundations were illusory, and that when it intervened to try to put things right and make a better world it often—as Zygmunt Bauman has so eloquently shown —wreaked havoc.2 But then it recognizes, and this is crucial, that the pluralist diaspora apparently favored by postmodernism raises problems that are just as difficult. Not only is it clear that we don’t live in a pluralist world in which everyone happily does their own thing, but it is also apparent that the broken fragments celebrated in postmodernism are just as much a product of modernism as its own streamlined coherences ever were. Postmodernism is, so to speak, the mirror image of modernism—and postmodernism’s response has simply been to break the smoothness and shatter that mirror. The argument, then, is that modernism and postmodernism exist together. They are each other’s creatures. And as they confront one another they tend to press us to make a choice between the homogeneities of centered storytelling on the one hand, and pluralism of fragmentation on the other. This, then, is a second version of what the book is about. It is an attempt to evade that choice.

But to make the argument I need to be more specific. So a third and more concise way of talking about the stories assembled in this book is to say that they are about fractional coherence. Fractional coherence, I will say, is about drawing things together without centering them.

Knowing subjects, or so we’ve learned since the 1960s, are not coherent wholes. Instead they are multiple, assemblages. This has been said about subjects of action, of emotion, and of desire in many ways, and is often, to be sure, a poststructuralist claim. But I argue in this book that the same holds for objects too. An aircraft, yes, is an object. But it also reveals multiplicity—for instance in wing shape, speed, military roles, and political attributes. I am saying, then, that an object such as an aircraft—an “individual” and ‘‘specific’’ aircraft—comes in different versions. It has no single center. It is multiple. And yet these

various versions also interfere with one another and shuffle themselves together to make a single aircraft. They make what I will call singularities, or singular objects out of their multiplicity.3 In short, they make objects that cohere.

But how do they do this? This is the major question that I tackle in this book. A question that, while speaking to the general issue raised by the so-called postmodern predicament, at the same time much more concisely refuses the pluralism implied by Lyotard’s multiple language games.

How, then, to think about this? I deploy a range of metaphors for thinking about the overlaps that produce singularity out of multiplicity. Many of these have grown up in the discipline of STS—of science, technology, and society. Interference, oscillation, Donna Har – away’s notions of ‘‘the established disorder’’ or the cyborg—these terms catch something important about the relations between singularity and multiplicity. But let me mention a further possibility here, that of fractionality. In mathematics fractals are lines that occupy more than one dimension but less than two.4 If we take this as a metaphor without worrying too much about the mathematics, then we may imagine that fractal coherences are coherences that cannot be caught within or reduced to a single dimension. But neither do they exist as coherences in two or three separate and independent dimensions. In this way of thinking, a fractionally coherent subject or object is one that balances between plurality and singularity. It is more than one, but less than many.

I want to suggest that Euro-American culture doesn’t really have the language that it needs to imagine possibilities of this kind. Its conditions of possibility more or less preclude the fractional. Indeed this is one of the reasons why the postmodern reaction—though it diagnoses some of the problems of modernism well enough—still finds itself trapped within a version of the modern predicament. For if things don’t cohere together to form a consistent whole, then it is usually assumed that they don’t cohere at all. So in common sense (as well as much academic and political discourse) the options tend to take the form of the binarism mentioned earlier: between, on the one hand, something that is a singularity because it holds together coherently; and, on the other, something that is broken and scattered, as in some kind of pluralism in which anything goes.5 Or between order Introduction 3

and its antithesis, chaos. Thus our languages tend to force us to choose between centers or dislocated fragments. Between the poles of‘‘drawing things together’’ and ‘‘the decentering of the subject.’’6 Or between single containers, such as ‘‘society,’’ and plural elements, such as ‘‘individuals,’’ that are contained within society. Fractionality, then, is one of the possible metaphors for trying to avoid such dualisms. For trying to wrestle with the idea that objects, subjects, and societies are both singular and multiple, both one and many. Both/and.

This, then, is the hope: that after the dualist contraries of centering and decentering, after the alternates of singularity and multiplicity, we might find ways of imagining fractionality. This, to be sure, is the hope of a number of scholars and is certainly one of the lessons that we learn from parts of poststructuralism.7 But the program, it seems to me, has not yet found good ways of performing itself—and least of all of doing so empirically. This leads to the fourth significance for the stories that I tell in the book. A fourth way of beginning.

This starts with a question: How should we write? How might we write about multiplicity in a way that also produces the effects of singularity? Or about singularity in a way that does not efface the performances of multiplicity? In this book I do not respond to this question by offering a single recipe or a formula. Instead I choose to proceed less directly and more allegorically. Or, more precisely, I try to make something, to create it rather than simply telling about it. For this book explores complexity, heterogeneity, and interference not simply by talking about them, but also, and maybe more importantly, by trying to perform them.

I believe that if we have not managed to attend very well to the fractional coherences of multiple objects and subjects, this is not simply because we have not properly faced the facts. It also has to do with how we investigate our subjects and objects and, in particular, with the ways in which we tell about them. It has, in short, to do with the character of social-science writing. Notwithstanding work in several social-science traditions, we are, to use a phrase, insufficiently selfreflexive aboutthe way in which we write.8 And aboutwhatis implied when we write in one way rather than another. So my hypothesis is that we have not yet recognized and allowed the difficult subjectivities that are needed for fractional knowing. In this book I also help to

bring such less direct ways of knowing into being. The book, then, is an intervention, a performance of fractional ways of knowing.

Perhaps it would have been possible to make a grand narrative about decentered and yet coherent objects. I take it that this is one of the features of Andrew Pickering’s work on the ‘‘mangle of practice,’’ a metaphor that otherwise does work which has much in common with what is attempted in this book: an inquiry into ontology, into what is made, rather than what is represented.9 And the thought of working in terms of a single metaphor is attractive because it offers a key to complexity. And such keys, once in place, are easily expressed and applied. Telling directly about what they tell, they are rendered easily transportable. To say it quickly, such is the dream of modernism in its search for foundational (or now postfoundational) grounds, and it is certainly the project of much contemporary social theory, to which the possibilities of allegory are foreign.10 But here I explore a less direct alternative by growing different stories alongside one another. Smaller narratives—a lot of smaller keys. Working in this way has a cost: we do indeed lose the possibility of an overall vision. But at the same time we also create something that was not there before: we create and make visible interferences between the stories. We bring new and unpredictable effects into being, effects which cannot be predicted or foretold from a single location. New forms of subjectivity.

To do this is to alter the character of knowing and writing. It is to render them multiple, decentered, or partially centered, in this place that refuses both modernism and postmodernism. If single accounts offering single keys make arborescences—treelike structures with beginnings, middles, and ends where everything important is held together in a centrally coordinated way—then multiple storytelling makes rhizomatic networks that spread in every direction. They make elaborations and interactions that hold together, fractionally, like a tissue of fibers.11 This results in texts that are uncentered, texts that are not singular. And yet, if the bet is right, it produces texts that have intersections, that hold together. That cohere.

So what does all this mean in practice? The answer is that the essays in this book tell specific stories about specific events. In doing so, they play upon recurrent themes to do with partiality, fractionality, interference, and collusion, while doing so in a manner that resists the

simplicities of an overall beginning, middle, and end. The book as a whole, then, is not treelike in structure. It is not an arborescence. Instead it takes the form of a rhizomatic network. It makes overlaps and juxtapositions, and it makes interference effects as a result of making these overlaps. So that is the fourth way of introducing the book. It is about writing fractionally.

But this suggests a fifth way of talking about the stories of the book, which has to do with how texts relate to the world. Perhaps, to be simple, we might speak of two possibilities. First, we may imagine that they tell about and thus represent a version of reality. If we think of writing in this way, then we distinguish between texts on the one hand, and what they represent on the other. The latter become something separate, out there, prior, removed. This means that we may stand outside and describe the world, and that when we do so we do not get our hands dirty. We are not in the world.

The alternative is to imagine, reflexively, that telling stories about the world also helps to perform that world. This means that in a (writing) performance reality is staged. And such a staging ensures that, everything else being equal, what is being performed is thereby rendered more obdurate, more solid, more real than it might otherwise have been. It becomes an element of the present that may be carried into the future.

So what do we perform when we write? There are various by now familiar possibilities. We may perform the world as a treelike structure: such is the desire of modernism as it seeks to perform its centered consistency into being. We may make fragments, which is, to be sure, the postmodern response. Or we may enact it rhizomatically, which is the allegorical or poststructural alternative that I am recommending.

In this alternative approach, no matter how stories are told about this aircraft, the TSR2, they do not simply describe something that happened once upon a time. They are rather, or also, away of helping to perform the aircraft. The stories participate in the aircraft. They add to the crowd of forms in which it was already among us, interfering with and diffracting earlier versions and thereby altering these forms. Perhaps slightly and locally. Perhaps unpredictably. But nevertheless altering them, and making a difference.

So the performativity of writing is a fifth way of introducing the

book, of describing the significance of its stories. But this in turn suggests a sixth possibility: that the book is about what it is to criticize, analytically and politically. Its fractional object is, as I have noted, a military aircraft. Why this should have been so is something that I explore in chapter 3. As is obvious, there is much to worry about in military aviation. Had the TSR2 ever been used in its nuclear role, the world would have stumbled into Armageddon. And, leaving aside the horrors of destruction, in the stories that follow we’ll come across ways in which the TSR2, even if it never killed, indeed performed social distributions—for instance those of gender or ethnicity.12 So yes, there is much to worry about here. But there is a problem if we start to criticize from what is supposed to be the outside because doing so ignores the performative character of storytelling that I have just been describing. In particular it ignores the fact that we are all mixed up in what we are describing. That, indeed, in one way or another we are helping to bring it into being. The fact that we are colluding with what we are describing, colluding to enact it into being.

The conclusion is that in a fractional and reflexive world the luxury of standing outside, criticizing, and correcting is no longer available.

Partly inside, partly outside, we are at least partially connected with our objects of study And if we seek to criticize then it also becomes important to reflect on the character of that involvement. We need to ask whether, and if so how, we share in what we do not like with those whom we do not like. And whether, and if so how, they share some of our own most valued ways of being.

This should not be misunderstood as a plea for political quietism.

Indeed, quite to the contrary. Thus if our writings perform reality, then they also alter it. Every time we act or tell, we also, at least putatively, make a difference. We always act politically. The only question is how do we do it?

This book interferes in a variety of ways, but in particular, or so I hope, it interferes with what we might think of as ‘‘project-ness.’’

This is the idea (which is also a performance) that many technologies and other social arrangements are properly narrated and organized as ‘‘projects,’’ ‘‘programs,’’ ‘‘operations’’ or other closely related terms such as “organization,” ‘‘system,’’ ‘‘network,’’ or even the ‘‘reflexive person.’’ These are objects that are somewhat linear, chronologically chained, and more or less centrally and teleologically ordered, and Introduction 7

that are also shaped in one way or another by their circumstances. Think of the TSR2 project. Or the Manhattan Project. Or the mission statements of organizations. Or indeed ‘‘the modern project.’’ Think of large technical systems, or actor-networks. This kind of telling and performing is a standard narrative trope in late modernity. And it is, of course, performative of that modernity, tending as it is told and enacted to order social relations in an image of projectness. It is one of the aims of this book to interfere with this trope, to erode the assump – tions performed in projectness, or at least to explore what is involved in their enactment. Thus, the sixth argument of the book in effect suggests to social scientists that, insofar as they frame what they tell in the form of stories about projects, they too are colluding in reproducing the conditions of projectness as an appropriate narrative form. No doubt this is not all bad. There are moments for this collusion. But if the arguments I am making carry any weight, then that performance tends to efface not only other possibilities but also the fractional conditions of the performance of singularity. And, to be sure, set limits to the conditions of possibility.

So there are at least six possible introductions, six ways of telling what the book is about: it is about an aircraft; it is about refusing the space provided by the division between modernism and postmodernism; it is about fractional coherence; it is about the reflexive forms of academic subjectivities needed to apprehend the fractional; it is about the performativity of writing; and it is about the collusions that necessarily follow from that performativity. Such are the themes that recur and interfere with one another throughout the book.

Each of the eight chapters that form the body of this book tells its own story and mobilizes its own resources, drawing variously on cultural studies, technoscience studies, feminist theory, philosophy, sociology, cultural anthropology, art theory and history, and semiotics.

Chapter 2 concerns the problem of multiplicity. It uses a version of semiotics to analyze how an aircraft sales brochure generates first a range of object positions and then coordinates them into a single aircraft. This analysis implies that coherent and single objects are effects or products. It also implies a shift from epistemology to ontology. This is because inconsistency between different performances

reflects failing coordination between different object positions rather than differences between external perspectives on the same object.

These, then, are two ofthe implications ifwe start to imagine thatnar – ratives are not about self-evidently singular objects but rather have to do with the enactment of fractional relations.

Chapter 3 deals with subjectivity, interpellation, and collusion. It describes how I was multiply interpellated by the TSR2, which implies that there is no such thing as a centered subject: like objects, subjects of knowledge are multiple or fractionally coherent. It also suggests that the interferences between these different subject positions are a valuable source of data. This means that if it is properly used, ‘‘the personal’’ is not confessional but analytical in character.

It also, however, means that when subjects are interpellated by objects, they are liable to find themselves colluding in the performance of certain narrative forms. Such was certainly so in the case of the TSR2.

Chapter 4 is about bias in favor of narrative continuity, and the ways in which discontinuities are effaced or deferred. In this chapter I identify three versions of narrative continuity: the chronology of genealogy and descent; the synchronicity of systematic connection; and depth hermeneutics, for instance in the form of background factors such as social interests that then shape more superficial phenomena. Despite their differences (and these, of course, have been rehearsed in extenso in social theory), each version performs a bias in favor of continuity and connection, while discontinuities are deferred into slippages between the different narrative forms and so tend to be effaced. This analysis implies that the difference between insider and outsider cannot be sustained: social scientists and participants alike tell their stories in terms of these narrative possibilities.

They collaborate to perform projectness and its conditions of possibility, which include a homogeneous space-time box with its own set of coordinates in the form of chronology and scale.

Chapter 5 concerns oscillation between singular presence and multiple absence. It considers an aerodynamic formalism that seeks to draw things together in an explicit and homogeneous manner. This formalism operates by simplifying and excluding almost everything —including other realities that are represented in algebraic form but cannot possibly appear on a sheet of paper. The formalism is thus Introduction 9

|

10 Introduction |

oscillatory: it necessarily makes absent that which it also seeks to make present. The paradox is that presence and coherence rest on their converse, that which cannot be made present and coherent. This means that absence and presence cannot be dissociated. Again, then, the underlying theme of the chapter is that objects are not singular, indeed not self-identical. That in their heterogeneity they are instead fractional and can only be apprehended fractionally. Chapter 6 is also about oscillation, this time oscillation first between text and pictures and second within the pictures themselves. The text of the brochure discussed in chapter 2 creates an aircraft that is practical, technically efficacious, and militarily invulnerable. The illustrations extend the performance of military invulnerability but also stress the nonpractical fact that to fly this aircraft is thrilling for a certain kind of heroic male subject. There are other genderings at work as well within the pictures. Though the aircraft itself is sometimes performed as a potent male, there are moments when it is made female in a version of the patriarchal fear of the power of woman performed in the oscillation between Madonna and whore. Thus the aesthetics of the illustrations (themselves noncoherent) interfere with the text in ways that are discursively illegitimate in order to perform a singular and obdurate aircraft that is strong and deadly. Chapter 7 is about decision making. It explores the assumptions about decision making in descriptions about the decision to cancel the TSR2. These include distinguishing between reality and fantasy; effacing the microphysics of power; performing certain places and times as discretionary; distinguishing between that which is important and that which is a mere ‘‘detail’’; and (in a further example of the oscillation between singularity and multiplicity) the erasure of differences between different decisions in a framing assumption that the decision taken was indeed one rather than many. This assumption of singularity thus makes it possible for different individual decisions to be made—but, I argue, it is necessary for different decisions to be made if a single decision is to be achieved. These, then, are narrative collusions to do with decision making not unlike those entailed in studying ‘‘projects.’’ Again there is oscillation. Chapter 8 returns to narrative performativity and collusion. It offers several accounts of the TSR2 project that reveal substantial overlaps. In particular, it suggests that the accounts are arborescent in form. |

Thus the stories all join in the performance of a single TSR2 and its projectness—and the work of building the kind of homogeneous space-time box described in chapter 4. This analysis suggests, once again, that that the distinction between insider and outsider doesn’t really work; that all accounts are performative (there is a discussion of Austin’s performatives and constatives); and that all collude in the reproduction of the conditions of possibility, which include a singular world and a singular object in which the oscillation with multiplicity is effaced. The hands of the storyteller are never clean.

Chapter 9 considers what comes after centering—for, given the gravitational pull of centered storytelling within the narrative traditions of modernism, escaping from singularity is difficult. Indeed, to talk of ‘‘escape’’ is not the right metaphor because it implies a postmodern fragmentation with the binarisms from which we need to escape. In this chapter I first consider the metaphor of the pinboard, the relationship between narratives or other performative depictions juxtaposed on a notice board. I suggest that this metaphor may help us to handle the performative character of our own ways of knowing in a manner that does not conceal their multiplicity. I then return to the question of the political. The question is, does an insistence on fractionality rather than the singularity of social structure imply political quietism? I argue that this is far from the case. Even leaving aside the often-collusive performativity of singular narrative, I suggest that the great social distributions familiar to sociologists and political commentators are all the more obdurate precisely because they are not singular but rather fractional in character. There is no ‘‘weak link’’ in an otherwise coherent structure. Rather there are partial and supple connections between distributions that help to secure dominance and reproduce the established disorder.

All of which—and this is the concluding thought—also demand fractional ways of knowing; skepticism about viewpoints that try to perform themselves as simply centered; and an ability to live and know in tension. This is one version of what a rigorous and politically interventionary social science that seeks to avoid both modernism and postmodernism might look like.

It was a sales brochure. About sixty pages long, it was published in 1962 by the British Aircraft Corporation. And it was trying to sell an aircraft, the TSR2, to its readers. But what was the TSR2? And who were the readers of the brochure?

It was a sales brochure. About sixty pages long, it was published in 1962 by the British Aircraft Corporation. And it was trying to sell an aircraft, the TSR2, to its readers. But what was the TSR2? And who were the readers of the brochure?

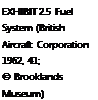

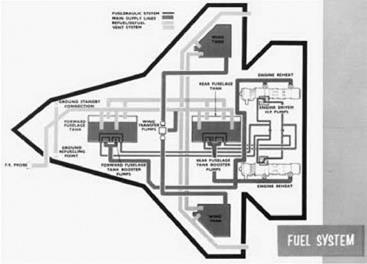

![]() There are historical responses to both these questions. TSR2 was a tactical strike and reconnaissance warplane being designed and built by the major UK aerospace manufacturer, the British Aircraft Corporation. And the brochure was intended for an elite readership: senior air force officers in the UK or in certain ‘‘friendly’’ countries, most notably Australia; senior civil servants, again in these selected countries; and no doubt a number of well-placed politicians. For the brochure was part of an effort to sell the aircraft, both in Britain but more particularly (since the Royal Air Force was already committed to its purchase) to possible overseas buyers.

There are historical responses to both these questions. TSR2 was a tactical strike and reconnaissance warplane being designed and built by the major UK aerospace manufacturer, the British Aircraft Corporation. And the brochure was intended for an elite readership: senior air force officers in the UK or in certain ‘‘friendly’’ countries, most notably Australia; senior civil servants, again in these selected countries; and no doubt a number of well-placed politicians. For the brochure was part of an effort to sell the aircraft, both in Britain but more particularly (since the Royal Air Force was already committed to its purchase) to possible overseas buyers.

Those, then, are brief versions of the historical answers. I offer them at the outset because I do not want to be accused of playing games, of withholding context, or of denying the obvious. But the direction in which I wish to move is different. For reasons that will become apparent I do not want to frame what I write in terms of the conventions of narrative history. Though this strategy, of course, brings its costs, I want instead to create a naive reader—a naive reader who knows nothing about the TSR2 or the potential readers of the brochure. And I want to use this fiction in order to learn something about how the brochure works. So the thought experiment is this: that we read excerpts from the brochure without making too many assumptions about its character, about what it is telling us, or about its likely readers. Something that is not possible if we arrive with the competences and the concerns of the historian.

So what happens if we do this?

© Brooklands Museum)

© Brooklands Museum)