efore proceeding further into the 20th century, we need to visit the labor movement in the United States. This phenomenon became a force and an institution in American industry that, beginning in the middle to late 19th century, has had a significant impact on national modes of transportation.

The development of trade unionism is highly correlated to the progression of industrialization. Although trade guilds existed from medieval times in Europe, they were composed of artisans who banded together to promote their craft, and to improve their products and methods. As such, guilds had an exclusionary aspect not seen in modern trade unions, which welcome wage earners of all kinds and strive to increase their membership numbers and power base.

Trade unions were formed as associations of workers as a natural counter-balance to owners. Historically, the formation of such groups was illegal under the laws of most countries. These groups were seen as hostile to the order of the day, revolutionary even, and their objectives were often sought through disorderly and violent means.

Prior to the Civil War, most of what could be called “industry” was controlled by small individual owners, often families, or sometimes

small partnerships. These industries included the cotton and woolen mills of New England, iron and steel factories of Pennsylvania and New York, the various short-line railroads that served their local areas all over the eastern United States, oil drillers in Pennsylvania, and coal mining operations in the Appalachian Mountain chain. Most of the wealth of the country lay in land ownership. The United States was primarily a nation of farmers.

The Civil War spurred development in most areas of industry. The woolen mills were called upon to clothe a million men with uniforms. Boots and saddles were needed from the leather industry. Union Army contracts for pork and cattle created the Chicago railroad stockyards and packing plants. The manufacture of iron and steel products boomed. The railroads proved their efficiency during the war through the movement of troops and materiel. And the railroads demanded more coal, iron, and oil.

After the end of the Civil War, railroad construction exploded. Some 35,000 miles of track were laid from 1866 to 1873. Building railroads was an expensive undertaking, and the use of the corporation found favor as a means of raising money. Corporations also became the preferred

form of business ownership and operation in most other industries. The shares of public corporations were traded on the stock exchanges of New York and Chicago, although large blocks of stock were owned by very wealthy individuals and families. In the days before any social regulation, corporations determined all the rules and working conditions of employment, including the hours to be worked and the rates of pay.

As industrialization grew, so did the organization of workers. Some of these organizations were more like fraternal organizations than unions, although they ultimately progressed into trade unionism and condoned work actions and strikes. Some of these groups were politically oriented, being populated by anarchists, socialists, and communists. The writings of Karl Marx, a German philosopher and bohemian, formed the basis of a philosophy of class strife (e. g., the haves against the have-nots, or class warfare), which was adopted by many groups. His Communist Manifesto, published in 1849, detailed the decline and fall of the capitalist economy and the ultimate triumph of the worker over the owner-class. Union leaders were usually the most aggressive of the workers.

The first railroad unions appeared in the 1860s. Their original purpose was to provide life insurance for their members, since life insurance companies refused to insure railroad workers due the high risk of injury and death. Railroads provided union organizers with the opportunity to organize workers on a national level instead of the local level usually associated with factories. Railroad unions were formed according to the class or craft of service that the employer rendered, whether engineer, fireman, conductor, or other.

After the Civil War, the railroads were the largest industrial employer in the United States. Money was flowing from the private sector into the railroads as they rapidly expanded and, as might be expected, the expansion rate proved to be too great. The overbuilding of the railroads, along with the great investment in money made by speculators, led to widespread economic failures. First profits dried up and then credit. The first industrially induced recession, known as the Panic of 1873, resulted in bank closures and depositor losses. The crisis caused the failure of more than 18,000 businesses, and 89 of the nation’s 364 railroads went bankrupt.

The relationship between the unions and the owners of the railroads was exceedingly antagonistic, with good cause on both sides. Although not illegal,1 unions were not recognized by business or by the government as quite legitimate. Union members often resorted to violence and civil disturbance; the railroads reciprocated with hired police forces and strike-breakers.

The economic conditions surrounding the Panic of 1873 resulted in the railroads cutting wages and terminating workers. In 1877, the first serious railroad strike of the new industrial age began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, and spread along the lines of railroad into Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, then on to the Midwest, St. Louis, and Chicago, becoming more violent as it went. Railroads across the country were brought to a standstill by rioting and bloodshed. In Chicago and St. Louis, a political group known as The Workingmen’s Party, which was the first Marxist-influenced political party in the United States, organized mobs of up to 20,000 demonstrators who battled police and federal troops in the streets.

Gradually, the troops suppressed both strikers and rioters city-by-city and, 45 days after it began, the Strike of 1877 was over. But the unions came out of the fray empowered by the knowledge of what their combined action could produce. The unions became better organized, and their numbers and membership grew. Their leaders espoused the general belief that they were justified in resorting to any means to overcome the power of the corporations. The Strike of 1877 was to mark the beginning of a particularly violent period in labor relations in the United States.

During the next decade there would be thousands of strikes, lockouts, and work interruptions in American industry as management-labor relations deteriorated further. But railroad strikes gained the most notoriety because of the widespread effect they had on the transportation system of the country. The biggest of all, called the Pullman Strike, occurred in 1894.

The Pullman Palace Car Company manufactured luxurious railway sleeper cars that were used by most railroad companies in their passenger trains. Due to another cyclical economic downturn (known as the Panic of 1893), production at the Pullman plant located in south Chicago was severely curtailed. As a result, the work force was reduced from 5,500 to 3,300, and the wages of the remaining workers were reduced by 25 percent. The workers at the Pullman plant were required to live in Pullman City, where the plant was located, in houses built by the company and leased to the workers. Everything in the town was owned by the company, and the company provided everything for the people, except saloons. When wages were reduced, the workers petitioned for a reduction of lease payments, but the company refused. This led to a strike by the Pullman workers in May 1894.

The American Railway Union (ARU) had been established just the year before, in 1893, by Eugene V. Debs, a former railroad worker and union officer in the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen. The ARU was unlike railroad trade unions in that it included railroad workers of all classes and crafts. It shortly became the largest union in the United States with over 140,000 members by 1894. In August 1893, it had called a strike of the Great Northern Railroad in response to a series of wage cuts. The shutdown of the railroad caused the company to reverse its wage decision. So when the Pullman Company cut wages, the ARU voted to join the Pullman strikers in order to bring all of the union’s clout down on Pullman.

The largest strike in the history of the United States ensued, involving hundreds of thousands of participants and 27 U. S. states and territories. One hundred twenty-five thousand railroad workers refused to handle Pullman sleeping cars or any trains in which they were placed. Thirteen railroads were forced to abandon all service in Chicago and 10 others were able to operate only passenger trains. The New York Times announced that the strike had become the greatest battle between labor and capital that had ever been inaugurated in the United States. Public sentiment shifted against the strikers as the disruption dragged on and as national transportation remained interrupted. Still, there was no federal intervention.

In July, the railroads began attaching the Pullman cars to U. S. mail cars, which then caused a disruption of interstate mail. Debs and other union officials were arrested for interfering with the delivery of U. S. mail. On July 2, a federal court injunction was issued against the ARU and its leaders. On July 3, President Cleveland ordered in federal troops to end the strike and to operate the railroads. On July 4, mobs of rioters began roaming the streets and destroying railroad property. Fires set by the mobs on July 6 and 7 destroyed 700 rail cars and seven buildings. Twelve people were killed by gunfire.

Debs was arrested on July 7 for violating the court order, and the violence began to subside. Trains began to move again and the strike whimpered to an end. Debs spent six months in prison.

These violent conflicts between organized labor and business during the latter part of the 19th century would lead to a federal legislation in the years to come designed to address the legitimate concerns of both labor and management. Eugene Debs would later be a candidate for President of the United States for the Socialist Party of America, standing for election four times between 1904 and 1920. His best showing, 6 percent of the vote, occurred in the election of

1912, and is the highest voter result for a Socialist Party candidate.

The disruption and violence of strikes were unpopular, and the courts routinely issued injunctions against unions on the basis of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. This statute, while enacted primarily to eliminate corporate monopolies, contained language that prohibited “every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce.” The courts interpreted this language as prohibiting strikes, which did, of course, restrain trade and commerce. In 1914, Congress passed the Clayton Antitrust Act, a further enactment against corporate trusts, but which contained provisions expressly exempting labor unions from the operation of the “restraint of trade” prohibitions found in the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The early part of the 20th century saw many changes in the American way of life.

• Horses and buggies were giving way to the automobile.

• Factories were going full blast, turning out production goods as never before.

• The assembly line, perfected by Henry Ford in the production of automobiles, was further aggravating the relations between workers and owners.

• The entry of the United States into World War I caused many young servicemen to be exposed to foreign culture for the first time, and to the bohemian ways of European life.

Still, America was very conservative during this time. The Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917 and its aftermath raised further concerns in this country as aggressive union activity seemed to bring the United States a step closer to socialist and communist ideology. Workers in heavy industry, such as mine workers, steel workers, and railroad workers, were highly organized and pursued a militant relationship with management.

The coming of the Great Depression during the 1930s and the Roosevelt New Deal, however, reflected a change in the way government looked at workers and their place in society. The New Deal brought a great wave of legislation directed toward fixing what was coming to be regarded as a broken economy and assisting those at the lower levels who functioned within it.

• Working conditions, hours, and rates of pay were the subjects of contention, and as the 20th century progressed, these conditions gradually improved due to the American system of self-determination through legislation.

• Child labor laws and a minimum wage were enacted.

• Uaws addressing the safety of workers were put on the books for the first time.

• Broad legislation protecting the right of workers to organize and to strike was passed.

• National work programs, like the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a relief program established by Presidential executive order, were instituted to alleviate the high unemployment numbers experienced due to the adverse economic conditions of the 1930s.

The postulations that Karl Marx had made with respect to the class warfare that, in his view, were inevitable were proved incorrect by the flexibility of the American governmental system. As substantial problems induced by the Industrial Revolution that affected the working population of the United States were perceived, Congress reacted with remedial legislation. These laws had the effect of acting like a relief valve in a pressure cooker, as workers perceived that their legitimate concerns were being addressed. Although union membership rose steadily from the latter part of the 19th century through the 1930s, it reached its peak in the 1950s. As economic conditions improved in the United States and worldwide, and as the workforce shifted from heavy industry to technology, union membership dropped off, and is still in the process of falling. Negative perceptions of thug-like union activity increased among the American population. Connections between some large unions, like the Teamsters, and the underworld or Mafia, were shown to exist. Unions have been accused of misappropriating members’ pension funds, and union officials have frequently been indicted and successfully prosecuted. The good that some unions accomplished was often overshadowed by these events.

The most important observation that can be made concerning the course of labor and management relations over the last century and a half is undoubtedly the success of the American system of government in coping with the often diametrically opposed positions of these participants in business. That system, based on the structure of the Constitution of the United States, has proven stronger than the differences that divide its population, and it has enabled a cooperative endeavor between labor and management that has benefited the world.

We will later consider specific developments in the country’s labor laws and their impact on the airline industry.

Endnote

1. Trade unions were adjudicated to be legal organizations in

the 1842 case of Massachusetts Commonwealth v. Hunt.

![]()

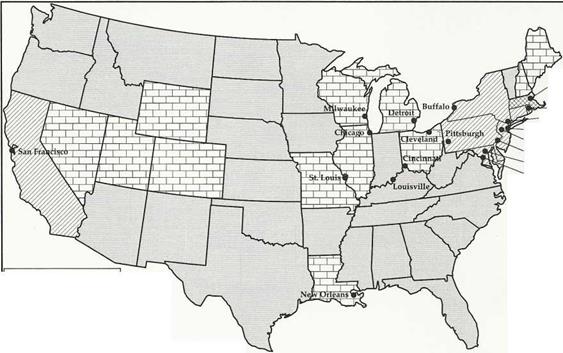

The pendulum had swung too far in the early and energetic days of railroading, and the government was now catching up to balance things out in the public interest. The days of unbridled capitalism in the railroad business were over. In the early years of the 20th century, the railroads were nearing what was to be their maximum trackage (miles of laid tracks), and they were just about to experience the effects of continuing industrial and technological development (Figure 3-4 displays the emergence of U. S. cities in 1880) that would lead to alternative forms of transportation that would overpower them. The days of the internal combustion engine, the open road, and the machines of the air lay just over the horizon.

The pendulum had swung too far in the early and energetic days of railroading, and the government was now catching up to balance things out in the public interest. The days of unbridled capitalism in the railroad business were over. In the early years of the 20th century, the railroads were nearing what was to be their maximum trackage (miles of laid tracks), and they were just about to experience the effects of continuing industrial and technological development (Figure 3-4 displays the emergence of U. S. cities in 1880) that would lead to alternative forms of transportation that would overpower them. The days of the internal combustion engine, the open road, and the machines of the air lay just over the horizon.