Transatlantic Flight

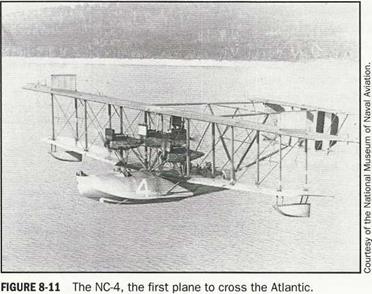

In 1919, the largest flying boats constructed by Curtiss, the NC-1 through the NC-4 (see Figure 8-11) were launched. In May, three of these, the NC-1, NC-3, and the NC-4, set out to make the first-ever transatlantic flight from Long Island to Lisbon, Portugal. The NC-1 and the NC-3 were forced down prior to reaching the Azores, but the NC-4, after 23 days en route, finally arrived in Lisbon—the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Although Curtiss did not produce more of the flying boats, the design advances he made were replicated or became the starting point for

|

all future improvements on aircraft hull design. Boeing became the leading flying boat exponent in the United States, along with Martin and Sikorsky, and produced the beautiful Clipper Ships of Pan American Airways fame. See Chapter 15.

America’s First Black Aviator and the Curtiss Connection

As a notable and related fact from newly discovered evidence,9 it appears that the first licensed African-American pilot, Emory Malick,10 received flight instruction from Curtiss at North Island in San Diego. Malick grew up in central Pennsylvania, where he built and flew his own gliders over the Susquehanna River. At some point (the evidence is still sketchy) he began flying powered aircraft and wound up at the Curtiss School, receiving his pilot’s license on March 12, 1912 from the Federation Aeronau – tique Internationale, number 105. Very little is currently known about his later life in aviation. It is likely that research in the near future may alter the course of history concerning black aviators in the United States.

з Postlude to the Wrights and Curtiss

The innovations, designs, and experimentation of Glenn Curtiss and the Aerial Experiment Association provide a study in contrast with those of the Wright brothers. The legacies of both groups continue to be studied and debated, but it is true that both were necessary to the development of aviation in the United States and in the world. It is ironic that the methods of the Wright brothers actually tended to inhibit flight when it was

|

Courtesy of The Malick Family Collection.

FIGURE 8-12 Emory Malick America’s First Black Aviator – 1912 Solo Flight. |

they who had initiated successful, controlled, and powered flight, while the methods of Curtiss tended to expand the concept and application of flight even though he was not first to suceeed. In spite of the combination of brilliance and dedication, on the one hand, and striving and enmity, on the other, that existed in the early world of aeronautics, the resolution of the differences between the two camps and their allies would be forthcoming, as we shall see in Chapter 9. [6] [7]

4. The Wrights’ commercial venture, like many to come, could only be deemed a failure. Orville Wright sold his interest in the company on August 26, 1915 for $250,000, one-fourth of its initial capitalization.

5. Wright Co. v. Herring-Curtiss Co. et ah, 177 F. 257 (W. D.N. Y. 1910).

6. See remarks in Appendix 2 by Dr. A. G. Bell on February 13, 1913, to the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution regarding Curtiss’ contributions to flight safety using floatplanes.

7. Wright Co. v. Herring-Curtiss Co. et al., 204 F 597 (W. D.N. Y. 1913).

8. Please see Appendix 3 for a discussion of the specific details of the Curtiss revisions to the Langley Aerodrome in 1914 and the flights made at Hammondsport that year. Note that this is a Smithsonian report from the year 1942 that had the approval of Orville Wright, and it is likely part of the reconciliation made between Orville Wright and the Smithsonian in order to allow the Wright machine to be taken to the Smithsonian for exhibition.

9. This reported information was first discovered by a white family member in 2004 in a family album. It was reported in Air & Space Magazine in the March 2011 issue.

10. 1881-1958.