Pan American Airways was to occupy a singular place in the annals of American aviation and in the relationship of an airline company with the U. S. government. What Pan Am came to be was mostly a product of the efforts of Juan Trippe, a true visionary, an indefatigable worker and thinker, a man of exceptional personal and professional contacts in both the world of business and government, and a man who stayed at the helm of his company longer than any of his contemporaries.

Trippe was instrumental in the formation and early operation of Colonial Airlines, one of the original airmail contract flyers in 1926 that ultimately became part of American Airways. His vision for that airline was much too aggressive for its conservative directors and stockholders, and Trippe was soon out. He had actually formed a small airline in 1924, before the financial benefits of airmail carriage became available, but it had been unable to survive. After Colonial Airlines, he was soon underway with his concept of an international airline, lining up financing from his wealthy friends and his father’s Wall Street contacts.

By 1927, Pan American was in the firm control of Juan Trippe and his friends. That year, wheeling, dealing, merging, and negotiating their way, the young men of Pan American had an airmail contract for the Key West, Florida to Havana, Cuba route. The contract stipulated that service must commence at the latest by October 19, 1927, and since other companies were waiting in the wings hoping Pan American would default, it became a matter of some importance to meet the deadline.

The Fokker Trimotors that Trippe had ordered to service the route had not shown up by that date, so the inaugural flight of Pan American Airways was hastily arranged on the dock at Key West on the drop-dead date. A transient floatplane pilot, bound for a job in Haiti, made a fortuitous fuel stop that day and unwittingly became a part of the grand history of Pan American, for a cash fee of $175.00. In fact, this unknown itinerate pilot was an essential catalyst to the creation of the Pan American Airlines that came to be.

Trippe’s vision was fueled not only by his expansive imagination and unbridled determination, but also by the circumstances in which America found itself in the late 1920s. The 1920s had been a decade of progress, experimentation, expansion, and success. World War I had caused Americans to look outward, mainly toward Europe, but now toward the untapped vast South American continent and the Eatin American connection. The region was ideally suited to air transportation because of its islandhopping availability. South America was also largely undeveloped, ruled by mountains, smothered by jungles, and it had largely skipped the era of railroad expansion. Transportation was about to go from pack mule and water skiff directly to air travel.

Europeans, mainly Germans seeking respite from the turmoil and inflation of their defeated nation, had opened up aerial trading routes to South America in 1919. They were expanding their influence along its eastern coast and up into the Caribbean. The expatriates formed a company called Sociedad Colombo-Aleman de Transposes Aereos (SCADTA) under the laws of Colombia that had become, as one of the world’s first airlines, an example of what aviation could do under extremely challenging conditions. In the process, SCADTA had become the pride of the people of Colombia.

The United States looked with some alarm at this development. The long-standing policy of the United States, as articulated in the “Monroe

Doctrine,”3 after all, essentially decreed the Americas for Americans, not Europeans, and certainly not the Germans. The governmental policy toward commercial aviation that was forming during the 1920s held that, while competition among business interests within the United States was good for the public, competition between American businesses outside its borders could be harmful. To properly compete with foreign airlines that were strongly supported by their governments, American international aviation would have to have some form of American government support and should follow some kind of governmental policy.

Pan American was ideally positioned to take advantage of this political and economic situation, and Juan Trippe commanded the confidence of the right people in government and business to enhance Pan American’s opportunities. The first Trippe ploy was to take advantage of a practice common in the domestic aviation market to “extend” route authority by fiat of the Postmaster General. This he did by securing an extension authority from the Key West to Havana route to Miami from Key West. After Lindbergh’s epic transatlantic flight and the ensuing public clamor and appeal that it engendered, Trippe signed Lindy up as a consultant, and Lindbergh became an integral part of the Pan Am strategy to extend its routes across the Caribbean and into Central America and then down into South America. In time, he would also figure prominently in Pan American’s westward Pacific expansion.

The second significant development was the passage by Congress in 1928 of the “Foreign Airmail Act.” This statute allowed the Postmaster General the discretion to grant routes to bidders that, in his opinion, were the “lowest responsible bidders that can perform the service satisfactorily.” The Act provided, in so many words, that only airlines capable of operating on a scale and in a manner that would project the dignity of the United States in Latin America would be granted the right to carry international mail. The only airline that fit this description was Pan American.

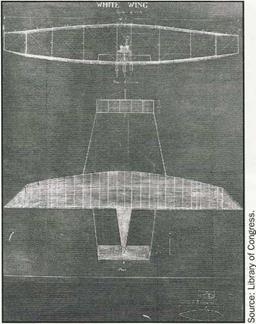

The first three airplanes purchased by Pan American were land-based Fokker Trimotors. (See Figure 15-9.) With these, the first passenger service between Key West and Havana was begun in January 1928. Given the lack of airports over the region and the fact that most of the flying was over water, Pan American made two significant decisions about its near-term future:

1. The line would employ flying boats to the

exclusion of other types of aircraft.

2, The line would fly only multiengine planes.

These decisions weighed favorably with the public and with the government.

It was also required that a form of navigation be developed that would allow flight over the trackless ocean. There were obviously no railroads to follow, no landmarks to navigate by, and no open fields to land in. Celestial navigation, long used in maritime transportation, was available, but it had serious limitations as the sole method of navigation for relatively fast moving airplanes. Voice radio was being experimented with on domestic air routes, but the equipment necessary to be placed on board approximated the size and weight of a small piano. Pan American had decided that radio was a near necessity from a safety standpoint, and it was searching for alternatives. An employee of RCA well versed in radio, Hugo Leuteritz, began experimenting with radiotelegraphy with devices that were installed on some of the airplanes. The equipment on board was very light, and the signals were clear and not beset by the static that made voice communication at these latitudes almost impossible. The procedure developed by Leuteritz utilized two land-based listening stations equipped with loop antennae that could pick up and then directionally locate the dots and dashes emitting from the en route aircraft. When the two stations drew lines from their separate positions to that of the aircraft, and the two lines crossed, the latitude and longitude thus determined were transmitted by the shore station to the radio operator aboard the

The public’s use of airmail for business and social purposes has mounted steadily.

(The decline during the fiscal year 1934, and in the subsequent interval required for repairing the decline, was caused by the cancellation of the airmail contracts.)

As volume has mounted, the unit cost to the government has steadily decreased. (Note figures at extreme bottom of chart.)

aircraft and its fix would be established. This method allowed pinpoint accuracy in making the desired landfall.

When the Sikorsky S-38 twin-engine flying boats arrived (see Figure 15-10), Pan American’s chief pilot, Captain Eddie Musick (see Figure 15-11), began to make survey flights beyond Havana to anticipated destinations even before the Post Office advertised for bids. It seemed that Pan American had an uncanny knack for already knowing where the routes were going to be offered, and for sewing up the local political and logistical support, including landing rights, necessary to make the routes immediately feasible and successful.

The next two routes awarded to Pan American were (1) from Havana to the Mexican island of Cozumel, then down Central America to Panama, and (2) from Havana to San Juan, Puerto Rico which suddenly increased Pan American’s annual airmail revenues from $160,000 to $2 million. Passenger service was then initiated on February 4, 1929, with Lindbergh at the controls flying the 100-mile per hour S-38. With the first flying boats,

service was commenced directly between Miami and Panama. (See Figures 15-12 and 15-13.) These two lucrative routes were soon followed by a third, from Miami to Mexico City, where linkups were made to the west coast of the United States. Airmail revenues soon topped $3 million a year.

Airmail routes in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America were consistently awarded only to Pan American in what was becoming the obvious policy of the United States government of allowing Pan American to be the “Chosen Instrument” of U. S. foreign influence.

This was despite the emergence of another American-formed airline, the New York, Rio, and Buenos Aires Airways (NYRBA), which began a head-on competition with Pan American in the region utilizing flying boats.

While Pan American went with the S-38, NYRBA ordered 14 of the Consolidated Commodore (see Figure 15-14), an amphibian designed as a patrol boat for the United States Navy, but which was converted to commercial use by September 1929. The Commodore mounted two 575-horsepower Flornet engines beneath its high wing. It was put into service on the Miami to Santiago, Chile route down the west coast of South America, a 9,000-mile route requiring seven days en route. It was also used on the east coast route to Buenos Aires.

Big names associated with NYRBA, like James Rand (of Remington Rand), former Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Aeronautics William McCracken, and William J. Donovan (credited with forming the Central Intelligence Agency), were unable by the middle of 1930 to secure even one foreign U. S. airmail contract. The airline was losing money on a then-gargantuan scale ($50,000 a month) and, without help

|

FIGURE 15-14 The Consolidated Commodore was originally designed as a patrol boat for the United States Navy, but was converted to commercial use by September 1929.

|

from the government, its backers saw no alternative to a sellout. On August 19, 1930, Pan American, with unofficial Post Office approval, bought out the NYRBA line. The next day, the Post Office Department advertised the east coast of South America airmail route. Pan American, of course, was the only bidder and it bid the maximum allowable rate.

By 1930, Pan Am was flying 20,000 route miles to 20 different countries, and it was still within the Western Hemisphere. (See Figure 15-15.) Trippe was obviously the American government’s “fair-haired child,” but his efforts at establishing transatlantic service were continuously thwarted by the British. Although the British agreed in principle with the proposition of bilateral rights between America and England, the standing position was that they were not physically or financially ready to compete with the United States, and until they were, no American rights would be granted. Because of the long distances, Europe was not considered a feasible destination without landing rights in Bermuda, and

since that island was strictly English, no European schedules of any sort were considered possible. Trippe turned his attention to the Pacific.

The range, in miles, of available aircraft was the most severely limiting factor in attempting a traverse of the vast Pacific Ocean. Sikorsky was the first to complete an aircraft design that attempted to address this problem, the S-40 flying boat. (See Figures 15-16 through 15-18.) This model boasted four engines, had a capacity

|

FIGURE 15-16 The S-40 was the first aircraft to address the problem of range over the vast Pacific Ocean.

|

of 44 passengers, and a range of 1,000 miles. The first S-40 was delivered to Pan American on October 10, 1931, and was christened by Mrs. Herbert Hoover at the Annapolis Naval Air Station. She broke a bottle of Caribbean seawater across the prow of the S-40, after which Juan Trippe dubbed the airplane a Pan American “Flagship.” Thus was the appellation “Clipper” born.

Shortly thereafter, the S-42 (see Figures 15-19 and 15-20), with a range of 2,520 miles, came off the line. This was still a bit short for the 2,410 mile San Francisco-to-Honolulu mn, if any reserve of fuel for weather or other contingencies were to be made. Trippe turned to Glenn Martin for help, while at the same time flying the S-42 configured with extra fuel tanks to assure another 500 miles.

With Findbergh’s help, it was Trippe’s plan that the Pacific would be conquered by way of Alaska, Japan, China, and points south, the kind of Great Circle route Findbergh had used in 1927 to Paris. No airmail contract had been awarded to Pan Am, but Trippe was proceeding anyway. He bagged a majority interest in an airline with operating rights in China called the China National Aviation Corporation, but then, in 1934, Japan was becoming militarily aggressive, and the U. S. State Department advised against the

proposed route. To go straight across the Pacific would require a route including Honolulu, Midway, Wake Island, and Guam before reaching Manila, Philippines. Aside from the fact that the Sikorsky aircraft was limited in range, there were absolutely no facilities on Midway, Wake, or Guam.

In typical fashion, Trippe had a freighter loaded with the necessary equipment, supplies, workmen, and supervisors and dispatched it to each of the proposed landing sites to construct the necessary passenger and aircraft support facilities, including terminals and hotels. With this service archipelago in place, and with

landing rights in Hong Kong, Pan American was poised to be the first transpacific airline with service from the American to the Chinese coasts.

In October 1935, the first M-130 Martin flying boat was delivered (the first of three). (See Figures 15-22 through 15-24.) This craft was larger than any other flying at the time. It had a range of 4,000 miles configured for mail and 3,200 miles with 12 passengers, a cruising speed of 163 miles per hour and redundant hydraulic

and electrical systems. With the airmail contract secured, service was inaugurated for mail and cargo delivery on November 22, 1935, in a ceremony at the dock in San Francisco attended by Postmaster General Farley. In October 1936, with the support facilities now in place, passenger service across the Pacific Ocean began to Manila. A New Zealand route followed after Australia was blocked by the British, and then a second, southern transpacific route was initiated

|

FIGURE 15-22 In October 1935 the First M-130 Martin Flying Boat was delivered.

|

|

FIGURE 15-23 M-130 and Commodore at Dinner Key Terminal.

|

via Kingman Reef and Pago Pago. On April 21, 1937, the transpacific route was extended to Hong Kong, with connecting flights to destinations in China serviced by the Pan Am subsidiary, China National Aviation Corporation. Then, within a six-month period, December 1937 to the summer of 1938, Pan American suffered two highly publicized clipper accidents that brought unaccustomed criticism, both from the press and from government quarters. Chief Pilot Eddie Musick, who had surveyed the original Latin American routes 10 years before, was at the controls of an S-40 off of Somoa when it exploded in

midair. In July 1938, one of the three Martin 130 Clippers disappeared between the Philippines and Guam. The intense expansion of routes over the Pacific was taking a heavy toll and, while Pan Am banked over $ 1 million in profits from Latin American operations in 1938, it was losing large sums of money in the Pacific. Trippe turned his energies back to the Atlantic.

On February 22, 1937, the British Air Ministry issued Pan Am a permit to operate a regular air service between the United Kingdom and the United States via intermediate points in Canada, Bermuda, Ireland, and Portugal. The agreement by Pan Am to pool passengers and cargo with the British airline, Imperial Airways, had a lot to do with this breakthrough. Technological advances, however, followed shortly on the heels of diplomacy. On order from Pan American since 1936, Boeing in 1938 produced its B-314 clipper (see Figure 15-25), the largest aircraft to be used in scheduled service then or thereafter until the arrival of the jumbo jets of the late 1960s. This airplane was configured in two decks, had a speed of 193 miles per hour and a range of 3,500 miles, enough range to allow Pan American to fly right over Bermuda en route to Europe. It carried 74 passengers seated or 40 passengers in the sleeping berth configuration. The Clipper went into the Pacific route service on February 22, 1939. (See Figures 15-26 and 15-27.)

In the Atlantic, Pan American launched its passenger service between New York and Marseille, France, on June 28, 1939 with the Dixie Clipper, a Boeing 314A, followed on July 8, 1939, by Yankee Clipper service from New York to Southampton.

Summary of Airlines’ Condition

The effects of the Great Depression were lessening by 1938. The economy was recovering, jobs were being restored, and manufacturing was picking up, including in the aircraft industry.

Although the airlines’ income from airmail carriage was down from what it had been before 1934, passenger revenues were up and exceeded airmail revenue for the first time. Airlines began to expand their passenger facilities and corporate infrastructure, and their traffic and sales departments. The airline industry was beginning to

have an impact on the public and on the economy. As the government lost more control over the airlines because of the lessening effects of airmail revenue, and as the airlines began to develop passenger traffic and revenue, it was time for the government to put into effect some kind of comprehensive control of the industry.

The situation was not unlike that of the railroad industry with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, or the trucking and bus industry in the Motor Carrier Act of 1935, except for one thing: The airlines wanted regulation.

Endnotes

1. History. NASA. gov/SP—4406/chapl. html—from which much of this section was taken.

2. Pacific Air Transport v. U. S.; Boeing Air Transport v. U. S.; United Airline Transport Corporation v. U. S., 98 Ct. Cl. 649 (1942).

3. The Monroe Doctrine was first expressed by President James Monroe in the State of the Union address to Congress on December 2, 1823. According to this policy, the American continents (North and South America, and including Central America) were to be henceforth free of any further colonization attempts by any European power. This statement of American national interest implied the use of American military and economic power in its enforcement. International adventures by Spain and Portugal triggered this policy.