SHENZHOU 7: SPACE WALK

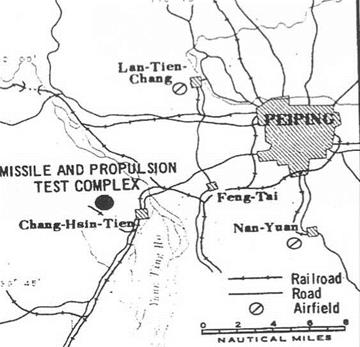

The mission profile for Shenzhou 7-а space walk – was announced as far back as 2005 and Chinese men were already practicing in the hydrotank in Moscow’s Star Town that February. Two years later, it was announced that work had begun on their spacesuit. By then, the astronaut training center had its own hydrotank in the training center, 10 m deep and 23 m across, with a crane to lower astronauts into the water and a team of six to eight divers to accompany the simulation. Zhang Baiman was announced as being in charge of the mission. On 10th July 2007, an Iliyushin 76 delivered the spacecraft to Jiuquan, the arrival being greeted by school children with flowers.

The first space walker, Zhai Zhigang, was named in the press in August and followed in the tradition of the first space walkers, Alexei Leonov (March 1965) and Ed White (June 1965). Zhai Zhigang came from Longjiang, Qiqihaer, Heilongjiang. His domestic circumstances were difficult, for his father was invahded and his mother ilhterate, although determined to get her children an education. Like Nie Haisheng, the Air Force was his route to a career. His colleagues reckon that he won selection because of his sanguine behavior – “he always wore a smile, whatever happened”, they said. His hobbies were fixing gadgets, calligraphy, and dancing. His companions were Liu Buoming and Jing Haipeng, both Air Force pilots. All were born in 1966, the year of the horse, considered a good omen in China. One difference from the 1965 missions was that the commander would make the space walk (back then, the commander was the man who stayed inside). Liu Buoming would join the space walk but remain mainly inside the cabin, while Jing Haipeng stayed in the fully pressurized command module.

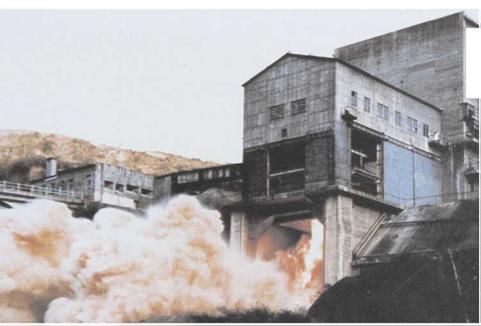

For the mission, China had bought nine Orion suits from Russia in April 2004 – three flight suits, two low-pressure training suits, and four suitable for hydrotank tests. From them, China had built its own suit, called the Feitian. For purposes of comparison, the space walker would wear the Chinese Feitian, but a second yuhangyuan would wear an Orlan suit in the depressurized orbital cabin. For their own suit, they tested both Russian-style oxygen-nitrogen (air) Orlan suits and Ughter

|

Zhai Zhigang’s Feitian. China tested two suits, the other being the Russian Orion. Courtesy: Mark Wade. |

American-style oxygen-only suits at 0.3 atmospheres but which require prebreathing for about a half-hour, as well as preventative measures against fire and the bends, deciding on the American system. The suit weighed 110 kg, had an endurance of 7 hr, and carried 1.9 L of water [12]. A number of other important changes were made. First, the exterior of the orbital module was stripped down so as to make a clear path for the space walkers. The solar panels were removed, as were 16 thrusters. In their place, the designers installed handrails, five air bottles, two cameras, a 40-kg subsatellite, and an experimental package. The primary purpose of the mission was to make a space walk and, once that was accomplished, Shenzhou would return to the Earth, mission duration being set at 68 hr.

For tracking, five comships were deployed: Yuan Wang 1 and 2 in the eastern Pacific, Yuan Wang 3 in the Atlantic, and Yuan Wang 5 and 6 in the north Pacific, supplemented by 12 tracking stations (including the overseas ones in Malindi, Swakopmund, Karachi, and Santiago), as well as the Tian Lian data relay satellite over the Indian Ocean. This time, tourists were invited to watch the launch, the fee being ¥15,000 (€1,500).

The CZ-2F was brought out to the pad on 23rd September 2008 and fuelled up. The three yuhangyuan held a press conference the following day, the 24th, and met the president. On the afternoon of 25th September, they suited up and traveled to the launch pad in the transfer van, to be greeted by a noisy crowd of workers, children, and well-wishers. The three men made their way to the launch station, where they stopped, saluted the launch commander, announced their readiness to carry out their mission, and, to further jostling and cheering, mounted the lift. They shd in turn into the command cabin through chutes in the orbital module.

It was night by the time the count concluded at 21:10 China time. The engines of the CZ-2F gushed yellow and orange flame with black smoke and began to rise in the night sky. It could be seen ascending into a typical ice-clear Jiuquan night, bending over in its climb, making the distinctive “cross of Korolev” shape of clustered burning engines. In a few minutes, they were in orbit of 200-337 km, 42.4°, raised on the fifth orbit to 330-337 km. Over Honolulu, amateur American trackers picked up signals on 2,224 MHz. Shenzhou 7 benefitted from the Space Environment Prediction Centre, set up in 1998, which updated its forecast radiation levels every 8 hr and confirmed that it was safe to go ahead with the space walk. Chinese doctors had meantime developed a medicine to combat space sickness – a combination of difenidol, theotydramin, promethazine, and cofferine, taken both before launch and before the space walk. Combining American and Russian experience with traditional Chinese medicines, a new pill was introduced to combat fatigue and improve performance during spaceflight, called the taikong yangxin.

The long-awaited space walk took place on 27th September, the third day of flight, on the 29th orbit. It had been deliberately delayed to then so as to enable any symptoms of early-mission pace sickness to pass. Pre-breathing and anti-decompression precautions were carried out for the Feitian. The whole event was relayed live on Chinese television and its worldwide feed, beginning when Shenzhou 7 was passing over Malindi. There was a brief gap in signal as it left Malindi and was picked up by Tian Lian 1, which was to cover the crucial period of the space walk. Viewers could see the hatch being opened by the two yuhangyuan from within the orbital module. Later, the unfolding events would be followed on the outside by a backward-facing camera mounted on the front of the orbital module.

Zhai Zhigang and Liu Buoming had difficulty opening the hatch. Even though the cabin had depressurized, there was still sufficient air outgassing from items in the cabin to apply pressure on the hatch – identical to difficulties experienced by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldin when they tried to open their lunar module hatch for their walk on the Moon. Zhai Zhigang was the first to emerge in his Feitian suit and could be seen coming out of the hatchway with the length of Shenzhou in the foreground and the blue Earth in the background. With his body now well out of the

|

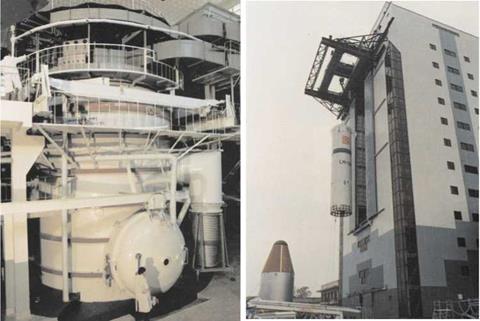

Shenzhou 7 seen in orbit from the BX-1 micro-satellite after the space walk. Courtesy: COSPAR China. |

hatch, he waved to all the viewers, greeting the Chinese people and all other viewers. Grabbing the handrail, he attached two tethers, one of which must be connected at a time. He then moved entirely out of Shenzhou, swam vertically, and, holding a small Chinese flag, waved it aloft to the world.

In the meantime, Liu Buoming emerged from the orbital module in his Russian – made Orlan suit. He stood by while Zhai Zhigang retrieved a small panel of experimental samples and handed it back to him inside. The purpose of the experimental package was to test 80 individual items of 11 types of solid lubricants and polymers and compare them with a ground sample: once back on the ground, the erosive nature of the space environment was apparent. After 14 min outside, Zhai Zhigang came back in and closed the hatch. Viewers watched the two yuhangyuan waiting in the orbital module for re-pressurization. Although it was a short space walk, this was very much in line with the duration of the Leonov and White space walks 40 years earlier. Depressurization time was 45 min, of which hatch open time was 22 min. Later, China intended to develop a manned maneuvering unit so that an astronaut could use its engines to move freely up to some distance away, without a tether. Several hours later, the subsatellite was released from the front of the orbital module. Later, the orbital module began its period of independent flight, making six changes of path, testing engines that would later be used on the Tiangong orbital station.

The following morning, the three yuhangyuan prepared to return to the Earth. The landing was again carried live on Chinese television. Retro-fire took place at 09:50 UT and, at 10:25, a dramatic image of the single parachute filled the screen, cameras following the cabin down all the way to touchdown at 10:36, the actual landing taking place behind a low hill. Cameras followed jeeps as they fanned out across the Mongolian grasslands and helicopters quickly touched down beside the cabin. Shenzhou had landed on its side and the hatch was soon open. In mission control, where Prime Minister Wen Jiabao was the principal visitor, there was relief and joy.

The crew was required to remain in the cabin for a half-hour for acclimatization so, in the meantime, water bottles were passed inside. Liu Buoming was first to emerge, followed by Zhai Zhigang and then Jing Haipeng. They were quickly seated in director’s chairs before being given flowers and making thank-you speeches. Later, they were brought away for a hero’s welcome in a motorcade with garlands of flowers. Mission time was 68 hr 28 min. With a full crew on a short mission, there was little scope for experiments on Shenzhou 7, but, echoing experiments carried out by the Soviet Union on Korabl Sputnik 2 in August 1960, Shenzhou 7 carried muscle cells to study the effects of spaceflight, finding that they became quite degraded over the short period of the mission. After the mission, the three yuhangyuan went on tour around the country. Shenzhou, with a Feitian suit and a Sokol suit, Zhai Zhigang’s gloves and flag, the recovered external samples, as well as a working model of Banxing were exhibited in the science museum in Hong Kong.

The 40-kg subsatellite provided quite a postscript for the mission. Called Banxing (“companion satellite”), built in Shanghai, it had its own thrusters and propulsion system for station-keeping and maneuvering. It appears to have been an initiative of the Academy of Sciences, like the Chuangxin micro-satellites. The satellite was developed by the Shanghai Satellite Engineering Centre with Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. It had, for the first time in China, a gallium arsenide solar array powering a lithium ion battery. Lead designer was Zhu Zhencai. The propulsion system used liquid ammonia vaporization. Following its spring ejection, its original orbit was the same as Shenzhou at the time, at 329-338 km, but, over the next week, it maneuvered first around Shenzhou and, later, its orbital module, maintaining a distance of 4-8 km for 25 orbits, practicing station-keeping with the orbital module. It operated within an ellipsoid of between 3,800 m and 7,600 m (figures of 540 m-20 km were also given), adjusting it six times, concluding its mission in January 2009. There were reports that it then moved away to a distance of 470 km, only to return to the orbital module. There was nothing new about such distance-and-chase maneuvers – they had been done by the USSR in the 1980s with the Czechoslovakian MAGION subsatellites – but it was a first for China. The subsatellite made a total of 13 maneuvers during its 100-day primary mission.

Banxing had two cameras, one wide-view and one narrow-view. Over 1,000 images were sent back by its two cameras, although only a small number – albeit excellent ones – were published. In January 2009, engineers reported that they were still in contact with the small spacecraft, which still had some fuel left. According to the subsequent mission report, Banxing demonstrated “inspection and proximity

alone-track relative posiiion km

The spiraling ellipses of the BX-1 flight pattern. Courtesy: COSPAR China.

operations” and tested new technologies such as gallium arsenide solar cells, lithium batteries, a micro-ammonia thruster, micro-attitude tracking controller, cameras with double-focusing systems, and a micro-USB responsor [13].

Banxing had a second postscript. American analyst Richard Fisher used data made available by the US Strategic Command to show that, 4 hr after its launch, Banxing flew to 45 km to the right of and below the ISS. Although the satellite was

released when the two were 500 km apart, at 15:07 UT, Banxing would have passed close to the ISS while they were overflying the sea between Australia and New Zealand. According to Fisher, the close pass arose either because the micro-satellite was out of control at the time, which was dangerously irresponsible, or there was a surreptitious maneuver to test on-orbit interceptions [14]. Banxing burned up on 29th October 2009, while the orbital module lasted longer, to 4th January 2010.