Meanwhile, the navy’s Polaris missile had made more far-reaching contributions. Until Polaris A1 became operational in 1960, all U. S.

long-range missiles had used liquid propellants. These had obvious advantages in their performance, but their extensive plumbing and large propellant tanks made protecting them in silos difficult and costly. Such factors also made them impractical for use on ships. After the operational date of Minuteman I in 1962, the Department of Defense began phasing out liquid-propellant strategic missiles.34

Meanwhile, given the advantages that liquid propellants enjoyed in terms of performance, their head start within the defense establishment, and the disinclination of most defenders of liquids to entertain the possibility that solid propellants could satisfy the demanding requirements of the strategic mission, how did this solid-propellant breakthrough occur? The answer is complicated and technical. But fundamentally, it happened because a number of heterogeneous engineers promoted solids; a variety of partners in their development brought about significant technical innovations; and although interservice rivalries encouraged the three services to development separate missiles, interservice cooperation ironically helped them do so. Despite such cooperation and the accumulating knowledge about rocket technology, however, missile designers still could not foresee all the problems that their vehicles would develop during ground and flight testing. Thus, when problems did occur, rocket engineers still had to gather information about what had caused problems and exercise their ingenuity to develop solutions that would cope with the unexpected.

Meanwhile, given the advantages that liquid propellants enjoyed in terms of performance, their head start within the defense establishment, and the disinclination of most defenders of liquids to entertain the possibility that solid propellants could satisfy the demanding requirements of the strategic mission, how did this solid-propellant breakthrough occur? The answer is complicated and technical. But fundamentally, it happened because a number of heterogeneous engineers promoted solids; a variety of partners in their development brought about significant technical innovations; and although interservice rivalries encouraged the three services to development separate missiles, interservice cooperation ironically helped them do so. Despite such cooperation and the accumulating knowledge about rocket technology, however, missile designers still could not foresee all the problems that their vehicles would develop during ground and flight testing. Thus, when problems did occur, rocket engineers still had to gather information about what had caused problems and exercise their ingenuity to develop solutions that would cope with the unexpected.

By the time that Polaris got under way in 1956 and Minuteman in 1958, solid-propellant rocketry had already made the tremendous strides forward discussed previously. But there were still enormous technical hurdles to overcome. The problems remaining to be solved included higher performance; unstable combustion; the inadequate durability of existing nozzle materials under conditions of heat and exposure to corrosive chemicals from the exhaust of the burning propellants; a lack of materials and technology to provide light but large combustion chambers so the burning propellants had to overcome less mass during launch; and ways to terminate combustion of the propellant immediately after the desired velocity had been achieved (for purposes of accuracy) and to control the direction of the thrust (for steering).35

Once the navy had overcome the bureaucratic obstacles to developing its own, solid-propellant missile, the Special Project Office (SPO) under Adm. William F. Raborn and Capt. Levering Smith achieved breakthroughs in a number of these technical areas. In early January 1956, the navy had sought the assistance of the Lockheed Missile and Space Division and the Aerojet General Corpora-

tion in developing a solid-propellant ballistic missile. The initial missile the two contractors and the SPO conceived was the Jupiter S (for “solid"). It had enough thrust to carry an atomic warhead the required distance, a feat it would achieve by clustering six solid rockets in a first stage and adding one for the second stage. The problem was that Jupiter S would be about 44 feet long and 10 feet in diameter. An 8,500-ton vessel could carry only 4 of them but could carry 16 of the later Polaris missiles. With Polaris not yet developed, the navy and contractors still were dissatisfied with Jupiter S and continued to seek an alternative.36

One contribution to a better solution came from Atlantic Research Corporation (ARC). Keith Rumbel and Charles B. Henderson, chemical engineers with degrees from MIT who were working 240 for ARC, had begun theoretical studies in 1954 of how to increase Chapter 6 solid-propellant performance. They learned that other engineers, including some from Aerojet, had calculated an increase in specific impulse from adding aluminum powder to existing ingredients. But these calculations had indicated that once aluminum exceeded 5 percent of propellant mass, performance would again decline. Hence, basing their calculations on contemporary theory and doing the cumbersome mathematics without the aid of computers, the other researchers abandoned aluminum as an additive except for damping combustion instability. Refusing to be deterred by theory, Rumbel and Henderson tested polyvinyl chloride with much more aluminum in it. They found that with additional oxygen in the propellant and a flame temperature of at least 2,310 kelvin, a large percentage of aluminum by weight yielded a specific impulse significantly higher than that of previous composite propellants.37

ARC’s polyvinyl chloride, however, did not serve as the binder for Polaris. Instead, the binder used was a polyurethane material developed by Aerojet in conjunction with a small nitropolymer program funded by the Office of Naval Research about 1947 to seek high-energy binders for solid propellants. A few Aerojet chemists synthesized a number of high-energy compounds, but the process required levels of heating that were unsafe with potentially explosive compounds. Then one of the chemists, Rodney Fischer, found “an obscure reference in a German patent" suggesting “that iron chelate compounds would catalyze the reaction of alcohols and isocyanates to make urethanes at essentially room temperature." This discovery started the development of polyurethane propellants in many places besides Aerojet.

In the meantime, in 1949 Karl Klager, then working for the Office of Naval Research in Pasadena, suggested to Aerojet’s parent

firm, General Tire, that it begin work on foamed polyurethane, leading to two patents held by Klager, along with Dick Geckler and R. Parette of Aerojet. In 1950, Klager began working for Aerojet. By 1954, he headed the rocket firm’s solid-propellant development group. Once the Polaris program began in December 1956, Klager’s group decided to reduce the percentage of solid oxidizer as a component of the propellant by including oxidizing capacity in the binder, using a nitromonomer as a reagent to produce the polyurethane plus some inert polynitro compounds as softening agents. In April 1955, the Aerojet group found out about the work of Rumbel and Henderson. Overcoming explosions due to cracks in the grain and profiting from other developments from multiple contributors, they discovered successful propellants for both stages of Polaris A1.

These consisted of a cast, case-bonded polyurethane composition including different percentages of ammonium perchlorate and aluminum for stages one and two, both of them featuring a six-point, internal-burning, star configuration. With four nozzles for each stage, this propellant yielded a specific impulse of almost 230 lbf – sec/lbm for stage one and nearly 255 lbf-sec/lbm for stage two. The latter specific impulse was higher in part because of the reduced atmospheric pressure at the high altitudes where it was fired, compared with stage one, which was fired at sea level.38

These consisted of a cast, case-bonded polyurethane composition including different percentages of ammonium perchlorate and aluminum for stages one and two, both of them featuring a six-point, internal-burning, star configuration. With four nozzles for each stage, this propellant yielded a specific impulse of almost 230 lbf – sec/lbm for stage one and nearly 255 lbf-sec/lbm for stage two. The latter specific impulse was higher in part because of the reduced atmospheric pressure at the high altitudes where it was fired, compared with stage one, which was fired at sea level.38

The addition of aluminum to Aerojet’s binder essentially solved the problem of performance for Polaris. Other innovations in the areas of warhead size plus guidance and control were necessary to make Polaris possible, but taken together with those for the propellants, they enabled Polaris A1 to be only 28.6 feet long and 4.5 feet in diameter (as compared with Jupiter S’s 44 feet and 10 feet, respectively). The weight reduction was from 162,000 pounds for Jupiter S to less than 29,000 pounds for Polaris. The cases for both stages of Polaris A1 consisted of rolled and welded steel. This had been modified according to Aerojet specifications resulting from extensive metallurgical investigations.

Each of the four nozzles for stage one (and evidently, stage two as well) consisted of a steel shell, a single-piece throat of molybdenum, and an exit-cone liner made of “molded silica phenolic between steel and molybdenum." A zirconium oxide coating protected the steel portion. The missile’s steering came from jetavators designed by Willy Fiedler of Lockheed, a German who had worked on the V-1 program during World War II and had developed the concept for the device while employed by the U. S. Navy at Point Mugu Naval Air Missile Test Center, California. He had patented the idea and then adapted it for Polaris. Jetavators for stage one were molybdenum

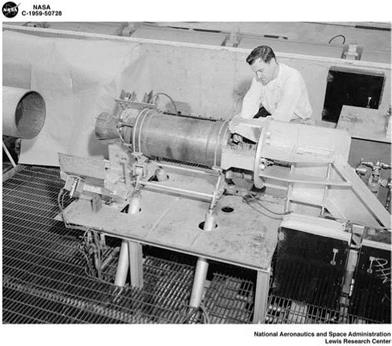

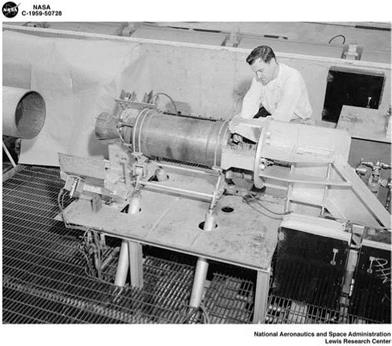

FIG. 6.4

An unidentified solid-rocket motor being tested in an altitude wind tunnel at NASA’s Lewis Research Center (later Glenn Research Center) in 1959, one kind of test done for Polaris. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

An unidentified solid-rocket motor being tested in an altitude wind tunnel at NASA’s Lewis Research Center (later Glenn Research Center) in 1959, one kind of test done for Polaris. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

rings with spherical inside surfaces that rotated into the exhaust stream of the four nozzles and deflected the flow to provide pitch, yaw, and roll control. The jetavators for stage two were similar.39

Besides requiring steering, the missile needed precise thrust termination when it reached the correct point in its trajectory. This could be achieved on liquid-propellant missiles simply by stopping the flow of propellants. For solids, the task was more difficult. The Polaris team used pyrotechnics to blow out plugs in six ports in front of the second stage at the proper moment in the trajectory. This permitted exhaust gases to escape and halt the acceleration so that the warhead would travel on a ballistic path to the target area.40

Flight testing of Polaris revealed, among other problems, a loss of control due to electrical-wiring failure at the base of stage one. This resulted from aerodynamic heating and a backflow of hot exhaust gases. To diagnose and solve the problem, engineers in the program obtained the help of “every laboratory and expert," using data from four flights, wind tunnels, sled tests, static firings, “and a tremendous analytic effort by numerous laboratories." The solution placed fiberglass flame shielding supplemented by silicone rubber over the affected area to shield it from hot gases and flame.41

Another problem for Polaris to overcome was combustion instability. Although this phenomenon is still not fully understood,

gradually it has yielded to research in a huge number of institutions, including universities and government labs, supported by funding by the three services, the Advanced Research Projects Agency, and NASA. Levering Smith credited Edward W. Price in the Research Department at NOTS with helping to understand the phenomenon. By this time, Price had earned a B. S. in physics and math at UCLA. In February 1960, he completed a major (then-classified) paper on combustion instability, which stated, “This phenomenon results from a self-amplifying oscillatory interaction between combustion of the propellant and disturbances of the gas flow in the combustion chamber." It could cause erratic performance, even destruction of motor components. Short of this, it could produce vibrations that would interfere with the guidance/control system. To date, “only marginal success" had been achieved in understanding the phenomenon, and “trial-and-error development continues to be necessary." But empirical methods gradually were yielding information, for example, that energy fluxes could amplify pressure disturbances, which had caused them in the first place.42 The subsequent success of Polaris showed that enough progress had been made by this time that unstable combustion would not be a major problem for the missile.

Long before Polaris A1 was operational, in April 1958 the DoD had begun efforts to expand the missile’s range from the 1,200- nautical-mile reach of the actual A1 to the 1,500 nautical miles originally planned for it. The longer-range missile, called Polaris A2, was originally slated to achieve the goal through higher-performance propellants and lighter cases and nozzles in both stages. But the navy Special Projects Office decided to confine these improvements to the second stage, where they would have greater effect. (With the second stage already at a high speed and altitude when it began firing, it did not have to overcome the weight of the entire missile and the full effects of the Earth’s gravity at sea level.) Also, in the second stage, risk of detonation of a high-energy propellant after ignition would not endanger the submarine. Hence, the SPO invited the Hercules Powder Company to propose a higher-performance second stage.43

Long before Polaris A1 was operational, in April 1958 the DoD had begun efforts to expand the missile’s range from the 1,200- nautical-mile reach of the actual A1 to the 1,500 nautical miles originally planned for it. The longer-range missile, called Polaris A2, was originally slated to achieve the goal through higher-performance propellants and lighter cases and nozzles in both stages. But the navy Special Projects Office decided to confine these improvements to the second stage, where they would have greater effect. (With the second stage already at a high speed and altitude when it began firing, it did not have to overcome the weight of the entire missile and the full effects of the Earth’s gravity at sea level.) Also, in the second stage, risk of detonation of a high-energy propellant after ignition would not endanger the submarine. Hence, the SPO invited the Hercules Powder Company to propose a higher-performance second stage.43

As a result, Aerojet provided the first stage for Polaris A2, and Hercules, the second. Aerojet’s motor was 157 inches long (compared with 126 inches for Polaris A1; the additional length could be accommodated by the submarines’ launch tubes because the navy had them designed with room to spare). It contained basically the same propellant used in both stages of Polaris A1 with the same grain configuration. Hercules’ second stage had a filament-wound case and a

cast, double-base grain that contained ammonium perchlorate, nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin, and aluminum, among other ingredients. The grain configuration consisted of a 12-point, internal-burning star. It yielded a specific impulse of more than 260 lbf-sec/lbm under firing conditions. The motor was 84 inches long and 54 inches in diameter, featuring four swiveling nozzles with exit cones made of steel, asbestos phenolic, and Teflon plus a graphite insert.44

This second-stage motor resulted from an innovation that increased performance by adding ammonium perchlorate to the cast, double-base process used in Hercules’ third stage for the Vanguard launch vehicle. Hercules’ ABL developed this new kind of propellant, known as composite-modified double base (CMDB), by 1958, evidently with the involvement of John Kincaid and Henry Shuey, 244 developers of the earlier cast, double-base process.45

Chapter 6 Even before 1958, however, Atlantic Research Corporation had developed a laboratory process for preparing CMDB. In its manufactured state, nitrocellulose is fibrous and unsuitable for use as an unmodified additive to other ingredients being mixed to create a propellant. Arthur Sloan and D. Mann of ARC, however, developed a process that dissolved the nitrocellulose in nitrobenzene and then separated out the nitrocellulose by mixing it with water under high shear (a process known as elutriation). The result was a series of compact, spherical particles of nitrocellulose with small diameters (about 1 to 20 microns). Such particles combined readily with liquid nitroplasticizers and crystalline additives in propellant mixers. The result could be cast into cartridge-loaded grains or case-bonded rocket cases and then converted to a solid with the application of moderate heat. Sloan and Mann patented the process and assigned it to ARC. Then, in 1955, Keith Rumbel and Charles Henderson at ARC began scaling the process up to larger grain sizes and developing propellants. They developed two CMDB formulations beginning in 1956. When ARC’s pilot plant became too small to support the firm’s needs, production shifted to Indian Head, Maryland. Because the plastisol process they had developed was simpler, safer, and cheaper than other processes then in existence, Henderson said that Hercules and other producers of double-base propellants eventually adopted his firm’s basic method of production.

Engineers did not use it for upper stages of missiles and launch vehicles until quite a bit later, however, and then only after chemists at several different laboratories had learned to make the propellant more rubberlike by extending the chains and cross-linking the molecules to increase the elasticity. Hercules’ John Allabashi at ABL began in the early 1960s to work on chain extenders and

cross-linking, with Ronald L. Simmons at Hercules’ Kenvil, New Jersey, plant continuing this work. By about the late 1960s, chemists had mostly abandoned use of plastisol nitrocellulose in favor of dissolving nitrocellulose and polyglycol adipate together, followed by a cross-linking agent such as isocyanate. The result was the type of highly flexible CMDB propellant used on the Trident submarine- launched ballistics missiles beginning in the late 1970s.46

Meanwhile, the rotatable nozzles on the second stage of Polaris A2, which were hydraulically operated, were similar in design to those already being used on the air force’s Minuteman I, and award of the second-stage contract to Hercules reportedly resulted from the performance of the third-stage motor Hercules was developing for Minuteman I, once again illustrating technology transfer between services. (Stage one of the A2 retained the jetavators from A1.) The A2 kept the same basic shape and guidance/control system as the A1, the principal change being more reliable electronics for the guidance/control system. By the time Polaris A2 became operational in June 1962, now-Vice Admiral Raborn had become deputy chief of naval operations for research and development. In February

Meanwhile, the rotatable nozzles on the second stage of Polaris A2, which were hydraulically operated, were similar in design to those already being used on the air force’s Minuteman I, and award of the second-stage contract to Hercules reportedly resulted from the performance of the third-stage motor Hercules was developing for Minuteman I, once again illustrating technology transfer between services. (Stage one of the A2 retained the jetavators from A1.) The A2 kept the same basic shape and guidance/control system as the A1, the principal change being more reliable electronics for the guidance/control system. By the time Polaris A2 became operational in June 1962, now-Vice Admiral Raborn had become deputy chief of naval operations for research and development. In February

1962, Rear Adm. I. J. “Pete" Gallantin became director of the Special Projects Office with Rear Adm. Levering Smith remaining as technical director.47

As a follow-on to Polaris A2, in September 1960, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara approved development of a 2,500-nautical – mile version of Polaris that became the A3. To create a missile that would travel an additional 1,000 nautical miles while being launched from the same tubes on the submarine as the A1 required new propellants and a higher mass fraction. The new requirement also resulted in a change from the “bottle shape" of the A1 and A2 to a shape resembling a bullet. In the attempt to help increase the mass fraction, Aerojet, the first-stage manufacturer, acquired the Houze Glass Corporation at Point Marion, Pennsylvania, and moved that firm’s furnaces, patents, technical data, and personnel to the Aerojet Structural Materials Division in Azusa, California, in early

1963. This acquisition gave Aerojet the capability to make filament – wound cases like those used by Hercules on stage two of Polaris A2. The new propellant Aerojet used was a nitroplasticized polyurethane containing ammonium perchlorate and aluminum, configured with an internal-burning, six-point star. This combination raised the specific impulse less than 10 lbf-sec/lbm.48

Unfortunately, the flame temperature of the new propellant was so high that it destroyed the nozzles on the first stage. Aerojet had to reduce the flame temperature from a reported 6,300°F to slightly

less than 6,000°F and to make the nozzles more substantial, using silver-infiltrated tungsten throat inserts to withstand the high temperature and chamber pressure. As a result, the weight saving from using the filament-wound case was lost in the additional weight of the nozzle. Hence, the mass fraction for the A3’s first stage was actually slightly lower than that for the A2, meaning that the same quantity of propellant in stage one of the A3 had to lift slightly more weight than did the lower-performing propellant for stage one of the A2.49

For stage two of the A3, Hercules used a propellant containing an energetic high explosive named HMX, a smaller amount of ammonium perchlorate, nitrocellulose, nitroglycerin, and aluminum, among other ingredients. It configured this propellant into an in – 246 ternal-burning cylindrical configuration with many major and mi – Chapter 6 nor slots in the aft end of the stage, creating a cross section that resembled a Christmas-tree ornament. This propellant offered a significantly higher specific impulse than stage two of Polaris A2. Also, the new stage two used a different method of achieving thrust vector control (steering). It injected Freon into the exhaust, creating a shock pattern to deflect the stream and achieve the same results as movable nozzles at a much smaller weight penalty.

A further advantage of this system was its lack of sensitivity to the temperature of the propellant flame. The Naval Ordnance Test Station performed the early experimental work on this use of a liquid for thrust vector control. Aerojet, Allegany Ballistics Laboratory, and Lockheed did analytical work, determined the ideal locations for the injectors, selected the fluid to be used, and developed the injectors as well as a system for expelling excess fluid. The Polaris A3 team first successfully tested the new technology on the second stage of flight A1X-50 on September 29, 1961. This and other changes increased the mass fraction for stage two of Polaris A3 to 0.935 (from 0.871 for stage two of the A2), a major improvement that together with the increased performance of the new propellant, contributed substantially to the greater range of the new missile.50

On April 30, 1960, the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division’s development plan for Titan II called for it to be 103 feet long (compared to 97.4 feet for Titan I), have a uniform diameter of 10 feet (whereas Titan I’s second stage was only 8 feet across), and have increased thrust over its predecessor. This higher performance would increase the range with the Mark 4 reentry vehicle from about 5,500 nautical miles for Titan I to 8,400. With the new Mark 6 reentry vehicle, which had about twice the weight and more than twice the yield of the Mark 4, the range would remain about 5,500 nautical miles. Because of the larger nuclear warhead it could carry, the Titan II served a different and complementary function to Minuteman I’s in the strategy of the air force, convincing Congress to fund them both. It was a credible counterforce weapon, whereas Minuteman I served primarily as a countercity missile, offering deterrence rather than the ability to destroy enemy weapons in silos.97

On April 30, 1960, the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division’s development plan for Titan II called for it to be 103 feet long (compared to 97.4 feet for Titan I), have a uniform diameter of 10 feet (whereas Titan I’s second stage was only 8 feet across), and have increased thrust over its predecessor. This higher performance would increase the range with the Mark 4 reentry vehicle from about 5,500 nautical miles for Titan I to 8,400. With the new Mark 6 reentry vehicle, which had about twice the weight and more than twice the yield of the Mark 4, the range would remain about 5,500 nautical miles. Because of the larger nuclear warhead it could carry, the Titan II served a different and complementary function to Minuteman I’s in the strategy of the air force, convincing Congress to fund them both. It was a credible counterforce weapon, whereas Minuteman I served primarily as a countercity missile, offering deterrence rather than the ability to destroy enemy weapons in silos.97

Meanwhile, as a result of Stiff’s discovery, Truax’s group at Annapolis began using 1,500-pound JATOs burning nitric acid and aniline on navy PBY aircraft in 1943. Both Truax and Stiff subsequently got orders to work at Aerojet, where Stiff devoted his efforts to a droppable JATO using storable, hypergolic propellants. Aerojet produced about 100 of these units, and some came to be used by the U. S. Coast Guard. In these ways, Aerojet became familiar with use of storable propellants, and Stiff joined the firm after completing his obligatory service with the navy.5

Meanwhile, as a result of Stiff’s discovery, Truax’s group at Annapolis began using 1,500-pound JATOs burning nitric acid and aniline on navy PBY aircraft in 1943. Both Truax and Stiff subsequently got orders to work at Aerojet, where Stiff devoted his efforts to a droppable JATO using storable, hypergolic propellants. Aerojet produced about 100 of these units, and some came to be used by the U. S. Coast Guard. In these ways, Aerojet became familiar with use of storable propellants, and Stiff joined the firm after completing his obligatory service with the navy.5 Scaling the WAC Corporal engine up to a larger size proved challenging. The first major design for a Corporal E engine involved a 650-pound, mild-steel version with helical cooling passages. Such a heavy propulsion device resulted from four unsuccessful attempts to scale up the WAC Corporal B engine to 200 pounds. None of them passed their proof testing. In the 650-pound engine, the cooling passages were machined to a heavy outer shell that formed a sort of hourglass shape around the throat of the nozzle. The injector consisted of 80 pairs of impinging jets that dispersed the oxidizer (fuming nitric acid) onto the fuel. The direction, velocity, and diameter of the streams were similar to those employed in the WAC Corporal A. The injector face was a showerhead type with orifices more or less uniformly distributed over it. It mixed the propellants in a ratio of 2.65 parts of oxidizer to 1 of fuel. The outer shell of the combustion chamber was attached to an inner shell by silver solder. When several of these heavyweight engines underwent proof testing, they cracked and nozzle throats eroded as the burning propellant exhausted out the rear of the engine. But three engines with the inner and outer shells welded together proved suitable for flight testing.11

Scaling the WAC Corporal engine up to a larger size proved challenging. The first major design for a Corporal E engine involved a 650-pound, mild-steel version with helical cooling passages. Such a heavy propulsion device resulted from four unsuccessful attempts to scale up the WAC Corporal B engine to 200 pounds. None of them passed their proof testing. In the 650-pound engine, the cooling passages were machined to a heavy outer shell that formed a sort of hourglass shape around the throat of the nozzle. The injector consisted of 80 pairs of impinging jets that dispersed the oxidizer (fuming nitric acid) onto the fuel. The direction, velocity, and diameter of the streams were similar to those employed in the WAC Corporal A. The injector face was a showerhead type with orifices more or less uniformly distributed over it. It mixed the propellants in a ratio of 2.65 parts of oxidizer to 1 of fuel. The outer shell of the combustion chamber was attached to an inner shell by silver solder. When several of these heavyweight engines underwent proof testing, they cracked and nozzle throats eroded as the burning propellant exhausted out the rear of the engine. But three engines with the inner and outer shells welded together proved suitable for flight testing.11 On launch seven of the Corporal E in January 1951, the vehicle landed downrange at 63.85 miles, 5 miles short of the targeted impact point. This was the first flight to demonstrate propellant shutoff and also the first to use a new multicell air tank and a new air – disconnect coupling. These two design changes to fix some of the problems on launch six increased the reliability of the propulsion system significantly. However, although the Corporal performed even better on launch eight (March 22, 1951), hitting about 4 miles short of the target, on launch nine (July 12, 1951) the missile landed 20 miles beyond the target because of failure of the Doppler transponder and the propellant cutoff system. The final “round" of Corporal E never flew. But the Corporal team had learned from the first nine rounds how little it understood about the flight environment of the vehicle, especially vibrations that occurred when it was operating. The team began to use vibration test tables to make the design better able to function and to test individual components before installation. This testing resulted in changes of suppliers and individual parts as well as to repairs before launch (or redesigns in the case of multiple failures of a given component.)15

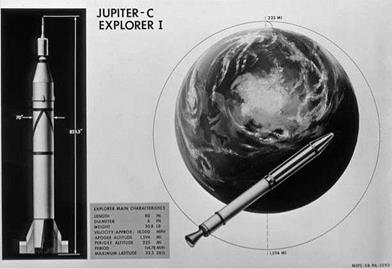

On launch seven of the Corporal E in January 1951, the vehicle landed downrange at 63.85 miles, 5 miles short of the targeted impact point. This was the first flight to demonstrate propellant shutoff and also the first to use a new multicell air tank and a new air – disconnect coupling. These two design changes to fix some of the problems on launch six increased the reliability of the propulsion system significantly. However, although the Corporal performed even better on launch eight (March 22, 1951), hitting about 4 miles short of the target, on launch nine (July 12, 1951) the missile landed 20 miles beyond the target because of failure of the Doppler transponder and the propellant cutoff system. The final “round" of Corporal E never flew. But the Corporal team had learned from the first nine rounds how little it understood about the flight environment of the vehicle, especially vibrations that occurred when it was operating. The team began to use vibration test tables to make the design better able to function and to test individual components before installation. This testing resulted in changes of suppliers and individual parts as well as to repairs before launch (or redesigns in the case of multiple failures of a given component.)15 Technical drawing of the Jupiter C (actually,

Technical drawing of the Jupiter C (actually,

LAUNCH VEHICLES FREQUENTLY USED MISsiles as first stages, but these required many modifications, particularly when they had to boost humans into space. Even for satellite and spacecraft launches, technology for the booster stages frequently represented modification of technologies missiles needed for their ballistic paths from one part of Earth to another. Thus, the history of the Thor-Delta, Atlas, Scout, Saturn, Titan, and Space Shuttle launch vehicles differed from, but remained

LAUNCH VEHICLES FREQUENTLY USED MISsiles as first stages, but these required many modifications, particularly when they had to boost humans into space. Even for satellite and spacecraft launches, technology for the booster stages frequently represented modification of technologies missiles needed for their ballistic paths from one part of Earth to another. Thus, the history of the Thor-Delta, Atlas, Scout, Saturn, Titan, and Space Shuttle launch vehicles differed from, but remained Soon after the army deployed Corporal I, Aerojet had occasion to develop its storable-propellant technology further with stage two of the Vanguard launch vehicle for the navy. The firm’s Aerobee sounding rockets, building on the WAC Corporal engine technology, had led to the Aerobee-Hi sounding rocket that provided the basis for the projected stage two. As requirements for that stage became more stringent, though, Aerobee-Hi proved deficient, and Aerojet had to return to the drawing board. The firm charged with designing Vanguard, the Martin Company, contracted with Aerojet on November 14, 1955, to develop the second-stage engine. Martin had determined that the second stage needed a thrust of 7,500 pounds and a specific impulse at altitude of 278 lbf-sec/lbm to provide the required velocity to lift the estimated weight of the Vanguard satellite.20

Soon after the army deployed Corporal I, Aerojet had occasion to develop its storable-propellant technology further with stage two of the Vanguard launch vehicle for the navy. The firm’s Aerobee sounding rockets, building on the WAC Corporal engine technology, had led to the Aerobee-Hi sounding rocket that provided the basis for the projected stage two. As requirements for that stage became more stringent, though, Aerobee-Hi proved deficient, and Aerojet had to return to the drawing board. The firm charged with designing Vanguard, the Martin Company, contracted with Aerojet on November 14, 1955, to develop the second-stage engine. Martin had determined that the second stage needed a thrust of 7,500 pounds and a specific impulse at altitude of 278 lbf-sec/lbm to provide the required velocity to lift the estimated weight of the Vanguard satellite.20 Moreover, a “unique design for the tankage" placed the sphere containing the helium pressure tank between the two propellant tanks, serving as a dividing bulkhead and saving the weight of a separate bulkhead. A solid-propellant gas generator augmented the pressure of the helium and added its own chemical energy to the system at a low cost in weight. Initially, Aerojet had built the combustion chamber of steel. It accumulated 600 seconds of burning without corrosion, but it was too heavy. So engineers developed a lightweight chamber made up of aluminum regenerative-cooling, spaghetti-type tubes wrapped in stainless steel. It weighed 20 pounds less than the steel version, apparently the first such chamber built of aluminum tubes for use with nitric acid and UDMH.23

Moreover, a “unique design for the tankage" placed the sphere containing the helium pressure tank between the two propellant tanks, serving as a dividing bulkhead and saving the weight of a separate bulkhead. A solid-propellant gas generator augmented the pressure of the helium and added its own chemical energy to the system at a low cost in weight. Initially, Aerojet had built the combustion chamber of steel. It accumulated 600 seconds of burning without corrosion, but it was too heavy. So engineers developed a lightweight chamber made up of aluminum regenerative-cooling, spaghetti-type tubes wrapped in stainless steel. It weighed 20 pounds less than the steel version, apparently the first such chamber built of aluminum tubes for use with nitric acid and UDMH.23 Meanwhile, given the advantages that liquid propellants enjoyed in terms of performance, their head start within the defense establishment, and the disinclination of most defenders of liquids to entertain the possibility that solid propellants could satisfy the demanding requirements of the strategic mission, how did this solid-propellant breakthrough occur? The answer is complicated and technical. But fundamentally, it happened because a number of heterogeneous engineers promoted solids; a variety of partners in their development brought about significant technical innovations; and although interservice rivalries encouraged the three services to development separate missiles, interservice cooperation ironically helped them do so. Despite such cooperation and the accumulating knowledge about rocket technology, however, missile designers still could not foresee all the problems that their vehicles would develop during ground and flight testing. Thus, when problems did occur, rocket engineers still had to gather information about what had caused problems and exercise their ingenuity to develop solutions that would cope with the unexpected.

Meanwhile, given the advantages that liquid propellants enjoyed in terms of performance, their head start within the defense establishment, and the disinclination of most defenders of liquids to entertain the possibility that solid propellants could satisfy the demanding requirements of the strategic mission, how did this solid-propellant breakthrough occur? The answer is complicated and technical. But fundamentally, it happened because a number of heterogeneous engineers promoted solids; a variety of partners in their development brought about significant technical innovations; and although interservice rivalries encouraged the three services to development separate missiles, interservice cooperation ironically helped them do so. Despite such cooperation and the accumulating knowledge about rocket technology, however, missile designers still could not foresee all the problems that their vehicles would develop during ground and flight testing. Thus, when problems did occur, rocket engineers still had to gather information about what had caused problems and exercise their ingenuity to develop solutions that would cope with the unexpected. These consisted of a cast, case-bonded polyurethane composition including different percentages of ammonium perchlorate and aluminum for stages one and two, both of them featuring a six-point, internal-burning, star configuration. With four nozzles for each stage, this propellant yielded a specific impulse of almost 230 lbf – sec/lbm for stage one and nearly 255 lbf-sec/lbm for stage two. The latter specific impulse was higher in part because of the reduced atmospheric pressure at the high altitudes where it was fired, compared with stage one, which was fired at sea level.38

These consisted of a cast, case-bonded polyurethane composition including different percentages of ammonium perchlorate and aluminum for stages one and two, both of them featuring a six-point, internal-burning, star configuration. With four nozzles for each stage, this propellant yielded a specific impulse of almost 230 lbf – sec/lbm for stage one and nearly 255 lbf-sec/lbm for stage two. The latter specific impulse was higher in part because of the reduced atmospheric pressure at the high altitudes where it was fired, compared with stage one, which was fired at sea level.38 An unidentified solid-rocket motor being tested in an altitude wind tunnel at NASA’s Lewis Research Center (later Glenn Research Center) in 1959, one kind of test done for Polaris. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

An unidentified solid-rocket motor being tested in an altitude wind tunnel at NASA’s Lewis Research Center (later Glenn Research Center) in 1959, one kind of test done for Polaris. (Photo courtesy of NASA) Long before Polaris A1 was operational, in April 1958 the DoD had begun efforts to expand the missile’s range from the 1,200- nautical-mile reach of the actual A1 to the 1,500 nautical miles originally planned for it. The longer-range missile, called Polaris A2, was originally slated to achieve the goal through higher-performance propellants and lighter cases and nozzles in both stages. But the navy Special Projects Office decided to confine these improvements to the second stage, where they would have greater effect. (With the second stage already at a high speed and altitude when it began firing, it did not have to overcome the weight of the entire missile and the full effects of the Earth’s gravity at sea level.) Also, in the second stage, risk of detonation of a high-energy propellant after ignition would not endanger the submarine. Hence, the SPO invited the Hercules Powder Company to propose a higher-performance second stage.43

Long before Polaris A1 was operational, in April 1958 the DoD had begun efforts to expand the missile’s range from the 1,200- nautical-mile reach of the actual A1 to the 1,500 nautical miles originally planned for it. The longer-range missile, called Polaris A2, was originally slated to achieve the goal through higher-performance propellants and lighter cases and nozzles in both stages. But the navy Special Projects Office decided to confine these improvements to the second stage, where they would have greater effect. (With the second stage already at a high speed and altitude when it began firing, it did not have to overcome the weight of the entire missile and the full effects of the Earth’s gravity at sea level.) Also, in the second stage, risk of detonation of a high-energy propellant after ignition would not endanger the submarine. Hence, the SPO invited the Hercules Powder Company to propose a higher-performance second stage.43 Meanwhile, the rotatable nozzles on the second stage of Polaris A2, which were hydraulically operated, were similar in design to those already being used on the air force’s Minuteman I, and award of the second-stage contract to Hercules reportedly resulted from the performance of the third-stage motor Hercules was developing for Minuteman I, once again illustrating technology transfer between services. (Stage one of the A2 retained the jetavators from A1.) The A2 kept the same basic shape and guidance/control system as the A1, the principal change being more reliable electronics for the guidance/control system. By the time Polaris A2 became operational in June 1962, now-Vice Admiral Raborn had become deputy chief of naval operations for research and development. In February

Meanwhile, the rotatable nozzles on the second stage of Polaris A2, which were hydraulically operated, were similar in design to those already being used on the air force’s Minuteman I, and award of the second-stage contract to Hercules reportedly resulted from the performance of the third-stage motor Hercules was developing for Minuteman I, once again illustrating technology transfer between services. (Stage one of the A2 retained the jetavators from A1.) The A2 kept the same basic shape and guidance/control system as the A1, the principal change being more reliable electronics for the guidance/control system. By the time Polaris A2 became operational in June 1962, now-Vice Admiral Raborn had become deputy chief of naval operations for research and development. In February One major area of difference between missile and launch-vehicle development lay in the requirement for special safeguards on launch vehicles that propelled humans into space. Except for Juno I and Vanguard, which were short-lived, among the first U. S. space-launch vehicles were the Redstones and Atlases used in Project Mercury and the Atlases and Titan IIs used in Project Gemini to prepare for the Apollo Moon Program. Both Projects Mercury and Gemini required a process called “man-rating" (at a time before there were women serving as astronauts). This process resulted in adaptations of the Redstone, Atlas, and Titan II missiles to make them safer for the human beings carried in Mercury and Gemini capsules.

One major area of difference between missile and launch-vehicle development lay in the requirement for special safeguards on launch vehicles that propelled humans into space. Except for Juno I and Vanguard, which were short-lived, among the first U. S. space-launch vehicles were the Redstones and Atlases used in Project Mercury and the Atlases and Titan IIs used in Project Gemini to prepare for the Apollo Moon Program. Both Projects Mercury and Gemini required a process called “man-rating" (at a time before there were women serving as astronauts). This process resulted in adaptations of the Redstone, Atlas, and Titan II missiles to make them safer for the human beings carried in Mercury and Gemini capsules. May 5, 1961, from Pad 5 at Cape Canaveral. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

May 5, 1961, from Pad 5 at Cape Canaveral. (Photo courtesy of NASA) For Titan II-Gemini, there were major problems with longitudinal oscillations in the engines, known as pogo (from their resemblance to the gyrations of the then-popular plaything, the pogo stick). These never occurred in flight but appeared in a severe form during static testing of second-stage engines. Surges in the oxidizer feed lines were causing the problem, which Martin engineers and others solved with suppression mechanisms. There was also the issue of combustion instability that occurred on only 2 percent of the ground tests of second-stage engines. But for man-rating, even this was too high. Aerojet (the Titan engine contractor) solved the problem with a new injector.6

For Titan II-Gemini, there were major problems with longitudinal oscillations in the engines, known as pogo (from their resemblance to the gyrations of the then-popular plaything, the pogo stick). These never occurred in flight but appeared in a severe form during static testing of second-stage engines. Surges in the oxidizer feed lines were causing the problem, which Martin engineers and others solved with suppression mechanisms. There was also the issue of combustion instability that occurred on only 2 percent of the ground tests of second-stage engines. But for man-rating, even this was too high. Aerojet (the Titan engine contractor) solved the problem with a new injector.6

In addition to a malfunction detection system, features added to the Titan II missile for astronaut safety included redundant components of the electrical systems. To help compensate for all the weight from the additional components, engineers also deleted vernier and retro-rockets, which were not necessary for the Gemini mission.8 From March 23, 1965, to November 11, 1966, Gemini 3 through 12 all carried two astronauts on the Gemini spacecraft. These missions had their problems as well as their triumphs. But with them, the United States finally assumed the lead in the space race with its cold-war rival, the Soviet Union. Despite lots of problems, Gemini had prepared the way for the Apollo Moon landings and achieved its essential objectives.9

In addition to a malfunction detection system, features added to the Titan II missile for astronaut safety included redundant components of the electrical systems. To help compensate for all the weight from the additional components, engineers also deleted vernier and retro-rockets, which were not necessary for the Gemini mission.8 From March 23, 1965, to November 11, 1966, Gemini 3 through 12 all carried two astronauts on the Gemini spacecraft. These missions had their problems as well as their triumphs. But with them, the United States finally assumed the lead in the space race with its cold-war rival, the Soviet Union. Despite lots of problems, Gemini had prepared the way for the Apollo Moon landings and achieved its essential objectives.9 Despite the problems with the second stage of Vanguard, the air force used a modified version on its Thor-Able launch vehicle, showing the transfer of technology from the navy to the air service. The Able was more successful than the Vanguard prototype for two reasons. One was special cleaning and handling techniques for the propellant tanks that came into being after Vanguard had taken delivery of many of its tanks. Also, Thor-Able did not need to extract maximum performance from the second stage as Vanguard did, so it did not have to burn the very last dregs of propellant in the tanks. The residue that the air force did not need to burn contained more of the scale from the tanks than did the rest of the propellant. Consequently, the valves could close before most of the scale entered the fuel lines, the evident cause of many of Vanguard’s problems.30

Despite the problems with the second stage of Vanguard, the air force used a modified version on its Thor-Able launch vehicle, showing the transfer of technology from the navy to the air service. The Able was more successful than the Vanguard prototype for two reasons. One was special cleaning and handling techniques for the propellant tanks that came into being after Vanguard had taken delivery of many of its tanks. Also, Thor-Able did not need to extract maximum performance from the second stage as Vanguard did, so it did not have to burn the very last dregs of propellant in the tanks. The residue that the air force did not need to burn contained more of the scale from the tanks than did the rest of the propellant. Consequently, the valves could close before most of the scale entered the fuel lines, the evident cause of many of Vanguard’s problems.30