The Punctuated Equilibrium Model provides a useful tool for better understanding trends within the space policy arena. In particular, it supplies metrics that can be applied to evaluate whether these long-term movements predetermined SEI’s fate. A mixture of policy image and venue indicators was drawn upon to conduct this assessment. These results provide a mixed picture regarding the potential for human exploration of Mars to reach the national agenda and obtain support for successful adoption. During the first 30 years of the space age, backing for both the space program and human exploration of Mars fluctuated a great deal within the American public and key institutional venues. Throughout this period, Mars exploration never reached the same levels of support that other projects (e. g., Project Apollo, Space Shuttle, and Space Station) enjoyed. While several indicators suggest there was growing support for the space program in general (and crewed Mars exploration in particular) by the late 1980s, a dramatic 20-year decline in space program budgets called into question the viability of a costly new initiative.

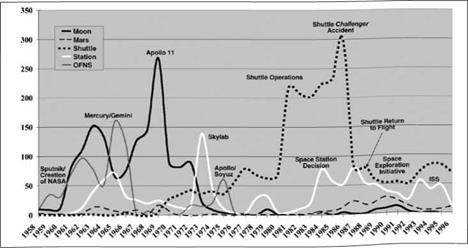

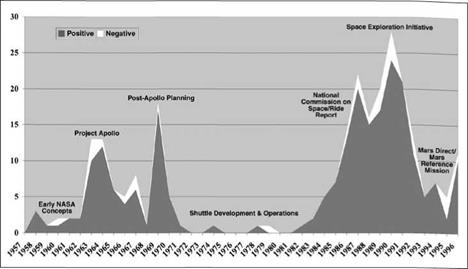

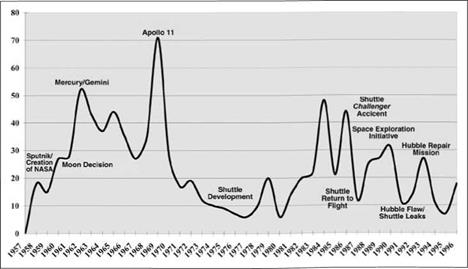

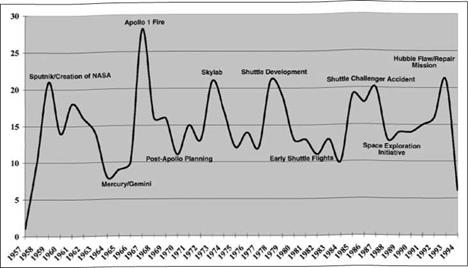

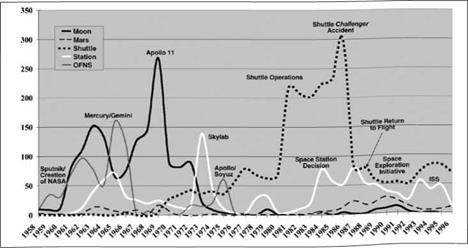

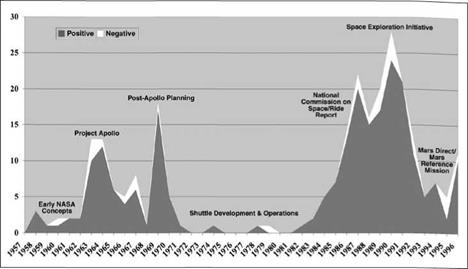

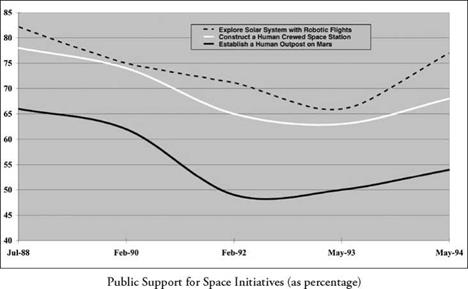

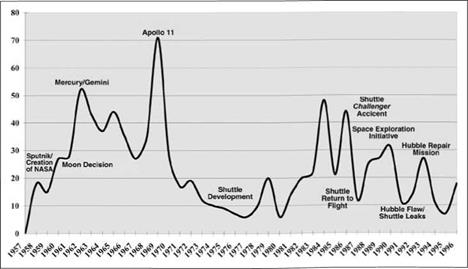

Baumgartner and Jones elected to study media coverage to gauge trends in policy image. The primary information source they utilized was The Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature.[344] They coded the number and tone of articles written in a given year to set the context for the agenda process in a given issue area. The first step in this process was to choose the proper keywords to ensure that all of the appropriate articles were included. The results were then entered into a spreadsheet, where they were further coded by different subtopics. One concern was that looking at only one index would not fully capture the nature of public opinion regarding specific issues. Baumgartner and Jones found, however, that “when we compare levels and tone of coverage in the Readers’ Guide with those of other major news outlets…it makes little difference which index one uses.”[345] For this book, the above methodology for monitoring the public agenda was adopted in almost every respect. Articles were tabulated from 1957 to 1996, coding them for topic and tone. Due to the extraordinarily large number of articles examining different aspects of the space program, only articles relating to human exploration were coded. Six broad topics were chosen to compare different exploration areas: Moon, Mars, Space Shuttle, Space Station, Orbital Flight (non-Shuttle or Station), and an “Other” category that encompassed articles relating to other destinations in the solar system or interstellar flight. To code each article’s tone, a basic question was asked: would an advocate of an American human exploration program, managed by a civilian sector agency, be happy or unhappy with the title? Over 6,500 articles were coded in this way.

|

Space Exploration in the Popular Press—By Program (number of articles) Based on an analysis of the Readers Guide to Periodical Literature, 1957-1996

|

|

Tone of Mars Exploration Coverage (number of articles)

Based on an analysis of the Readers Guide to Periodical Literature, 1957-1996

|

During the early years of the space age, while the popular press was clearly focused on NASA’s efforts to orbit the first American and send humans to the Moon, Mars exploration was largely overlooked. Media coverage for crewed missions to the red planet was trivial compared to other space efforts. Although there were only a small number of articles, media coverage of Mars exploration during the Apollo era was largely supportive, with nearly 90% of the items positive in tone. Coverage slowly increased and reached an initial peak of nearly 20 articles in 1969, when post – Apollo planning was taking place within the federal government. By the 1970s, in the aftermath of the failed effort to push crewed missions to Mars onto the national agenda, media coverage plummeted to at most one article every couple of years. During this period, the majority of media attention focused on Space Shuttle development, the Skylab space station, and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Flight Program. Over the course of the 1980s, media coverage of Mars exploration began growing again, although it was still dwarfed by the Shuttle and Space Station Freedom programs. This increase was the result of “softening up” activities like the Case for Mars conferences, the National Commission on Space, and the Ride Report. By the end of the decade, as SEI reached the national agenda, reporting of crewed Mars exploration represented a significant portion of total coverage. While the reporting was highly supportive, there was no massive increase in attention as there had been for Project Apollo. Regardless, coverage of Mars exploration reached all time highs after President Bush announced SEI, with over 20 articles written annually. In the aftermath of the initiatives failure, however, media attention plummeted. By the mid-1990s, fewer than ten articles were being written per year as the Clinton administration focused on completion of the International Space Station.

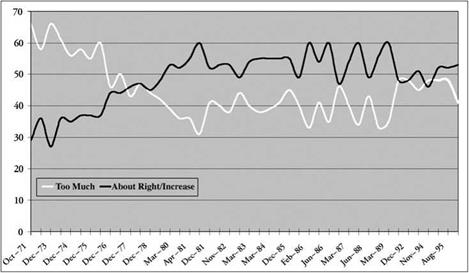

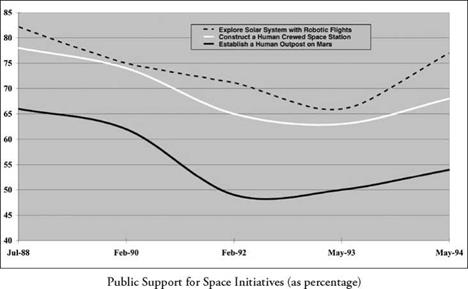

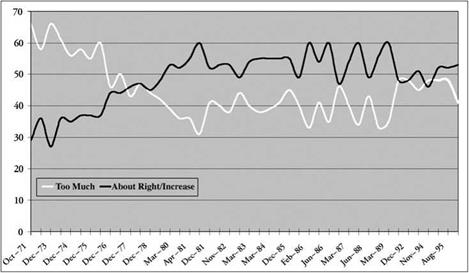

Baumgartner and Jones found that survey research, if available in a systematic form, is another data resource for observing changes in policy image. Survey research has become a progressively more important tool for policy analysts and policy makers.[346] The polling data utilized for this book was compiled by the NASA History Division and reveals interesting trends in mass public opinions regarding the American space program. During the post-Apollo planning period, the vast majority of the American public believed that the NASA budget was too large. This provides a compelling reason for the failure of human exploration of Mars to garner support from President Nixon. Over the next 20 years, however, this attitude toward the NASA budget shifted significantly. In the years leading up to the announcement of SEI, there was a relatively high level of support for the space program. By the late 1980s, the majority of Americans believed that NASA spending was either just right or needed to be increased. In 1989, the year that SEI was announced, that figure reached sixty percent for only the fifth time in the post-Apollo era. Despite this relatively high level of public support for NASA, human exploration of Mars was still seen as a lesser priority. Robotic exploration of the solar system and construction of a crewed space station consistently received more support from the general public. Regardless, when the initiative was announced, more than 60% of the public supported establishment of a human outpost on Mars.

As SEI began experiencing difficulties and NASA was dealing with problems in the Hubble and Shuttle programs, however, those numbers began dropping once again—falling to below 50% by December 1990. Although these numbers would eventually recover slightly, by that time the policy window for Mars exploration had already closed.

|

Public Opinion of NASA Spending (as percentage)

|

|

|

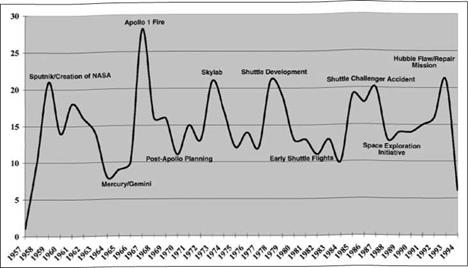

While examining media coverage and opinion polls provides information relating to policy image, other measures are needed to evaluate venue access. Four different indicators were selected for this book to monitor changes in venue access for space policy issues. The first indicator relied upon an analysis of the Congressional Information Service Abstracts (CIS annual)—a yearly compilation of data on Congressional hearings. In the late 1990s, Baumgartner and Jones established the Center for American Politics and Public Policy to provide researchers with tools to better understand the dynamics of policy change. Under the auspices of the center, more than 67,000 congressional hearings were classified using a common policy content code to ensure compatibility over time.[347] [348] [349] For the purposes of this book, the entire CIS annual dataset was downloaded. A separate dataset was created, which included only hearings that related to the American space program. This dataset included over 550 hearings covering the years from 1958 to 1994.11 The second indicator utilized to monitor changes in venue access, which will be discussed in concert with the CIS annual, relied upon an analysis of the Public Papers of the Presidents.11 For this study, a methodology similar to that used for coding the Readers’ Guide was employed. Presidential addresses and speeches were coded by topic from 1957 to 1996. This included all papers relating to the civilian space program. These papers were then used to assess trends in venue access for agenda items relating to the American space program.

During the 1960s, presidential support for the nations space program reached its apex. President Kennedy’s decision to send humans to the Moon initiated a decade of close White House attention.[350] Through the ’60s, Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon delivered well over 400 addresses and speeches relating to the civilian

space program. At the height of interest in Project Apollo, presidential addresses and speeches frequently topped 40 per year—and reached as high as 70. This indicated significant access to an important policy venue (e. g. The White House). Similarly, Congressional interest in space exploration peaked during this period.[351] In particular, there was a pronounced spike in congressional interest following the Apollo 1 fire that killed three astronauts (see Figure on page 152).

|

Trends in Presidential Attention (number of speeches/addresses)

Based on an analysis of the Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States, 1958-1996

|

|

Trends in Congressional Attention (number of hearings)

Based on an analysis of the ‘Policy Agendas Project,’ Center for American Politics and Policy

|

By the mid-1970s, the number of presidential speeches and addresses had plunged below ten annually as NASA concentrated on building the Space Shuttle and sending robotic probes to explore the solar system. While Congressional attention dipped below Apollo era levels as well, the number of space-related hearings remained relatively stable at about 15 a year. This was primarily due to annual appropriation and authorization hearings. As the Space Shuttle began operations during the 1980s, presidential addresses and speeches began slowly rising again—with increased interest surrounding the decision to build the Space Station and in the aftermath of the Challenger accident. Although Congressional interest remained steady during this period, there were noticeable spikes in interest surrounding the first Space Shuttle flight and as Congress held hearings following Challenger.

While presidential interest in the space program was relatively high during the SEI era, congressional support was not particularly robust. President Bush was clearly interested in the space program, as evidenced by his espousal of human missions to the Moon and Mars. During his presidency, he made a number of significant space policy speeches, most directly related to gaining support for SEI. Still, compared with presidential attention during the first decade of spaceflight and even during the Reagan administration, Bush made fewer annual speeches and addresses relating to the space program. On its face, it would appear that Mars exploration had only modest access to this important policy venue during the Bush presidency. This discounts, however, the important role played by Vice President Quayle and the Space Council staff during this period. Combining the involvement of Bush and Quayle with a dedicated internal policy staff to work on space issues, this administration was probably more engaged in this arena than any other during the post – Apollo period. In contrast, Congressional interest was relatively low at this time. After a peak following the loss of the Challenger, Congressional attention waned as the Bush administration was pushing for SEI. The next peak did not occur until the problems with the Hubble and Space Shuttle programs came to the fore. This indicates that during the post-Apollo period, Congress has been highly reactive to problems within the space program. At the same time, it has not been terribly engaged during relatively calm periods. The lack of access to this critical venue was likely a contributing factor in the eventual failure of SEI.

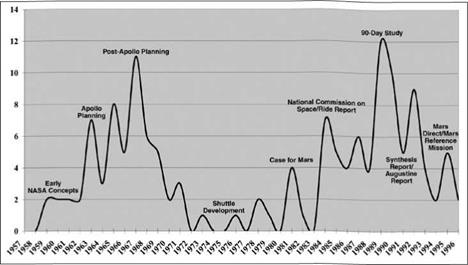

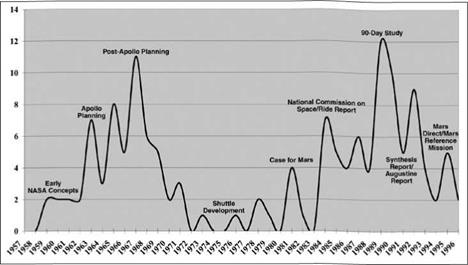

A third indicator utilized to monitor venue access relied upon an analysis of technical strategies for human exploration of the Moon and Mars. This metric provided insight into Mars explorations ability to garner attention within a key policy venue—the federal bureaucracy (e. g. NASA). In 1996, NASA Johnson Space Center Historian David Portree created a website called Romance to Reality: Moon and Mars Plans. It was a comprehensive catalog of classic, seminal, and illustrative human exploration plans. The majority of these studies were conducted under the auspices of government agencies and private sector companies.[352] The site included detailed summaries and descriptions of reports dating back more than five decades.[353] Portree emphasized studies that emerged as important to later mission planning, but also included reports that helped illustrate essential strategic architectures. For this book, the above reports were used to observe trends, both inside and outside the federal government, in the generation of Moon-Mars exploration plans. Each report from 1950 to 1996 was coded using the same three categories Portree employed: Moon plan, Mars plan, and Moon/Mars plan. Nearly 300 technical studies were coded in this way.[354]

During the course of the 1950s, eight major studies were conducted by government agencies and aerospace companies as part of the “softening up” process for Mars exploration. The following decade, as NASA was working full throttle to meet President Kennedy’s lunar landing deadline, more than 50 Mars exploration studies were conducted in preparation for a post-Apollo space program. Despite its growing

|

Technical Reports Focusing on Mars Exploration (number of studies) Based on an analysis of Romance to Reality: Moon and Mars Plans, 1957-1996

|

profile within the space agency, however, Mars exploration had relatively low visibility with the American public. Likewise, it was not supported by President Nixon or Congress—which led to its exclusion from post-Apollo planning. In the 1970s, NASA’s official interest in crewed exploration of the red planet basically disappeared. An illustration of this fact is that the space agency did not conduct one major Mars – related study from 1972 to 1985. At the same time, however, private actors kept the dream alive by generating over 20 reports. These were partially responsible for the Reagan administration’s decision to place human exploration beyond Earth orbit on the national agenda. By the time President Bush announced SEI, Mars exploration had greater access to the bureaucratic venue than at any other time in the first 40 years of spaceflight. During the four years of the Bush administration, over 35 different studies were conducted. The dilemma for the Space Council, however, was that the politically infeasible 90-Day Study became so closely associated with the initiative.

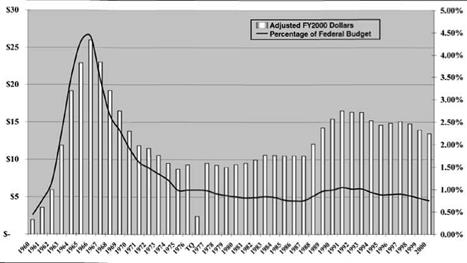

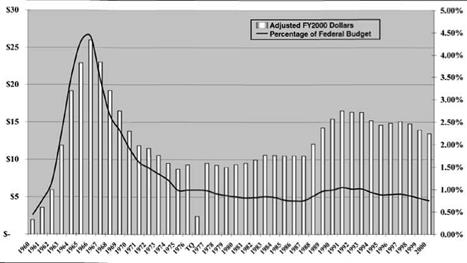

While the three preceding venue access indicators suggest that by the late-1980s there were favorable trends supporting a major new human spaceflight initiative, a final indicator paints a very different picture—the federal budget. At the height of Project Apollo, NASA’s budget was $6 billion, or about 4.5% of the entire federal budget. This represented an extremely large financial commitment to the American space program, which was allocated primarily in an effort to beat the Soviets to the Moon. By the time Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed in the Sea ofTranquil – ity, NASA’s budget had already begun a rapid decline. Although Congress remained

|

NASA Budget (In billions)

OMB, “Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2004: Historical Tables”

|

engaged in the space program during the next two decades, it was nevertheless steadily cutting NASA’s budget from its Apollo peak. The mid-1970s saw a budgetary low of $3-25 billion, with budgets increasing slightly into the early 1980s. More significantly, the NASA budget dropped to under 1% of the entire federal budget—where it would remain permanently except for a three-year period in the early 1990s. Despite the fact that it had experienced steadily decreasing resources, NASA continued to conduct its program planning by assuming that it would receive future budget increases. This tendency to overcommit itself did not foretell a positive result for NASA-led development of another major exploration initiative. While the Bush administration increased funding for NASA, the available resources were far below those available during the mid-1960s. There was little public or congressional support for dramatically increasing the NASA budget. This did not bode well for SEI, which as envisioned by the TSG would have required doubling or tripling the annual allocation for NASA.

Baumgartner and Jones’s approach to studying agenda change provides an interesting perspective for understanding larger themes within the American space program. Using policy image and venue access indicators not only reveals interesting trends, it provides insight into factors that helped SEI reach the national agenda but dramatically reduced its chances of gaining Congressional support. As discussed above, there have been striking shifts in media coverage over the past four decades. During the nine years after President Kennedy announced the Moon decision, over 2,100 human spaceflight-related articles were written (an average of 235 annually). During the subsequent nine years, as NASA was developing the Shuttle, under 1,200 articles were written (125 annually). The ten years after the Shuttle began operations, including those years following the Challenger accident, saw another upward shift with nearly 2,200 articles written (220 annually). This included increased coverage of Mars exploration, which was largely positive in tone. Finally, during the eight years after President Bush announced SEI, coverage plummeted to fewer than 1,000 articles (110 annually). This trend suggests that there have been relatively extended periods of general excitement about the space program within the general public (which resulted in significant media coverage), but that these periods have been followed by equally long periods where the public becomes disengaged. These declines in overall media attention seem to be correlated with periods of poor economic performance and tightening federal budgets. SEI came to the fore toward the end of a cycle of increased media coverage, which enhanced the likelihood it would successfully reach the national agenda. At the same time, however, an examination of past polling data reveals that economic forces were working against any dramatic increase in NASA’s annual appropriation. In the end, these budgetary pressures were far more important than any perceived public support for Mars exploration.

An analysis of the Public Papers of the Presidents and the CIS annual reveals that the White House and Congress are largely reactive when it comes to addressing space policy issues. Past presidents have delivered the majority of their speeches in reaction to programmatic successes and failures. Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon gave regular speeches during the triumphant Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs, while President Reagan spoke out primarily in the aftermath of the Challenger accident.[355] The fact that President Bush delivered a relatively large number of space-related speeches during his tenure suggests that the space program had significant White House access during this period. This is particularly true because there were no great successes or failures of a similar magnitude during Bush’s presidency. Combined with Vice President Quayle’s heavy involvement in space policy making, this represented one of the most active administrations in this issue area. Access to this important institutional venue made possible the elevation of SEI to the national agenda. The relative lack of congressional interest, however, tremendously reduced the initiative’s chances of actual adoption. The space program has enjoyed relatively stable congressional attention, with significant peaks after major failures (i. e., Apollo 1, Challenger, Hubble). When SEI was being considered, there was a clear lull in congressional interest as the legislature focused on an imposing budget crisis. While this did not necessarily preclude adoption of any new human spaceflight program, it did indicate that promotion of projects requiring large budgetary increases was ill-conceived.

An examination of past technical reports shows that there were two clear periods of interest in Mars exploration, one leading up to post-Apollo planning and another leading up to the announcement of SEI. Prior to both attempts to garner support for adoption of such a program, NASA and non-government actors conducted a steadily increasing number of studies that provided the technical background for the eventual policy alternatives that were considered. Particularly in the case of SEI, this indicates that significant bureaucratic forces were aligned to force an aggressive exploration program onto the national agenda. As discussed above, the fiscal constraints quashed these plans. The federal budget is the single most effective indicator for evaluating the potential for bringing about dramatic programmatic change at NASA. Budgetary trends expose Project Apollo as a clear outlier in the history of the space program, where a unique political environment led to the program’s adoption. Subsequent experience has proven that without the emergence of a similar crisis environment, the space program will not receive a large infusion of resources to carry out aggressive human spaceflight programs. SEI’s failure is the quintessential example of this lesson. Regardless of bureaucratic desires, technical plans for human exploration beyond Earth orbit must be fiscally feasible.

The policy image and venue access indicators utilized for this study provide a relatively consistent picture regarding the potential for SEI to reach the national agenda and to be successfully adopted. With regard to agenda setting, a combination of metrics suggests that Mars exploration would receive favorable consideration as the long-term goal of the human spaceflight program. These included increased media coverage of Mars exploration, general public support for the establishment of a Martian outpost, and a growing number of reports providing the technical details for such an undertaking. Combined with strong support from the Bush White House, this virtually guaranteed that the initiative would be pushed onto the national agenda. With regard to actual adoption, however, a number of other indicators suggest that SEI faced an uphill battle. Most important among these were fiscal constraints, limited public support for increased NASA budgets, and no congressional backing for expensive new programs. While a less costly Mars exploration program may have been able to gain approval under these circumstances, after the release of the 90-Day Study, the ultimate failure of SEI was assured.

While the above analysis provides some evidence that both the Policy Streams Model and Punctuated Equilibrium Model provide valuable insight into the rise and fall of SEI, a concluding discussion is in order to generalize these findings beyond this specific case study. This is logically assessed by answering a simple question: Do we know something about SEI we wouldn’t have without using these two models? There are at least three potential answers—a lot, a little, or nothing at all. It seems

like the most defensible answer lies in the middle. To start with, although we may instinctively have a sense of who the important actors are within a given policy community, Kingdon provides an effective framework for quantifying these beliefs. The survey used for this book was designed to determine whether the appropriate actors were involved in the policy process for SEI. While we may have come to the same conclusion even if we didn’t have the survey results, they provide some actual data to back up our assumptions. This survey, or some instrument like it, could just as easily be used to better understand the policy community for other science and technology issue areas. More importantly, it has the ability to provide policy makers with a real world tool for deciding who to engage during the agenda setting and alternative generation processes.

The operational indicators introduced by Baumgartner and Jones, and those developed specifically for this book, also provide a potentially valuable tool for science and technology researchers. Most of these indicators provide good data for large issue areas. For example, the data collected for this book provides revealing trends for space policy as a whole. The data is not as good, however, when one drills down to the next level of detail. Public opinion polls, presidential speeches, and congressional hearings can only be used to gauge large scale trends within an entire field. They cannot easily be used to examine specific issues within this area, such as interest in Mars exploration or space science or orbiting space stations. Although it requires a good amount of effort, it is possible to use data sources like media coverage and technical studies to gain some appreciation of interest in these more specific issue areas. Overall, however, these indicators are a bit cumbersome to use—although this would be made easier if this data, regarding space policy issues in particular, were readily available to policy makers. That is not currently the case, which makes the use of this set of indicators somewhat impractical in the real world.

Therefore, the Policy Streams Model and Punctuated Equilibrium Modelvs>iz provided an understanding of the failure of SEI that the case study alone may not have provided. We have better insight regarding who the important actors are within the space policy community, which reveals weaknesses in the agenda setting and alternative generation processes for SEI. We have a better insight regarding larger trends within the space policy arena (i. e., public opinion, congressional attention, federal budgets) that conspired against the adoption of this costly human spaceflight initiative. This type of data not only informs an academic work like this book, but can (and probably should) be used by policy makers in the real world. There does not seem to be any reason why these methodologies could not be applied widely within the science and technology policy field. While this would clearly require a good amount of work, both compiling the data and periodically updating it, the potential benefits for successful agenda setting and alternative generation processes would be worth the effort.