Human Exploration of Mars Reaches the Government Agenda

As these events were unfolding in Washington, President Bush was in Europe on a 10-day trip that included an address before the Polish National Assembly, a meeting with Solidarity leader Lech Walesa, a meeting with Hungarian leaders, and attendance at a G-7 summit in France. While he was away, Bush had essentially delegated decision-making responsibility for the exploration initiative to Vice President Quayle. Over the course of the previous month, Bush had discussed the development of the exploration initiative with Quayle at several of their weekly lunch meetings, but the president had essentially let his vice president make all the critical decisions with regard to the strategic plan. One important facet of their discussions was whether the Administration should set a target date of 2010 for completion of a Moon base and 2020 for an expedition to Mars. Although this debate continued up until the last moment, the two ultimately decided against specific deadlines because they feared it would adversely impact future budget deliberations. By early July, the President had fully committed to the program.[163]

On 14 July, Quayle chaired a meeting of the full Space Council to discuss the forthcoming announcement of the exploration initiative. Mark Albrecht recalled that “everyone lined up, thought it was a great idea and made a recommendation to the President that he go ahead and do this.” Thus, when Bush arrived back in Washington two days before the speech, everything was already in place for him to announce the new plan.[164] Vice President Quayle wrote in his memoirs that if the agenda setting process for SEI sounded like a. .somewhat ad hoc, improvisational way to think about going to Mars, you’re right. But what was important right then was to think big, to put a bit of ‘the vision thing’ back into the program, to get people excited about it once again, even if that meant getting ahead of ourselves.” Quayle believed the only thing that would enliven the American people was a restoration of wonder in the idea of sending people to explore space, not just orbit around the Earth.[165]

Before the new initiative was officially announced, the 17 July 1989 edition of Aviation Week and Space Technology (AW&ST) broke the story that a secret White House review was considering a human lunar base and Mars initiative. The article opened by stating, “A sharp debate has been sparked within the Bush Administration and Congress by Vice President Dan Quayle’s proposal that President Bush commit the U. S. this week to developing a manned lunar base as a stepping-stone to a manned flight to Mars. Under the proposal, the U. S. could build a lunar outpost by 2000-2010 and use the experience gained on the moon to develop that capability to mount a manned Mars mission by 2020.” The magazine reported that Quayle had been formulating the initiative in secret meetings with a group of NASA officials, Mark Albrecht, and White House Chief of Staff John Sununu. Administration officials were quoted as saying that President Bush would not make a Kennedy-style call for reaching Mars within a specific timeframe, instead endorsing “the lunar base and manned Mars concepts as overall 21st century goals [and deferring] specific program and budget decisions on these goals until NASA completes a more intensive assessment of the mission options.” The magazine reported that NASA’s budget would have to double within a decade to pay for the initiative. This was at the same time that the House Appropriations Committee was planning on cutting NASA’s FY 1990 appropriation by more than $1 billion, including a 50% decrease in funding for technologies key to Mars exploration. While Vice President Quayle recognized that the federal government faced serious budgetary limitations, he was quoted as saying that “when we have tight budgets, there will be winners and losers, but I am convinced a winner will be space.” Craig Covault of AWdrST reported that NASA leaders saw a presidential endorsement as an opportunity to seek increased funding and begin serious mission planning. Overall, the article was uncannily accurate and set the stage for President Bush’s upcoming address.[166]

On Thursday, 20 July 1989, with the decision in favor of an aggressive program for human exploration of the Moon and Mars made, President Bush prepared to announce the initiative at the anniversary celebration of Apollo ll’s landing on the Moon twenty years earlier. At shortly before 10:00 a. m., President and Mrs. Bush, accompanied by Vice President and Mrs. Quayle, departed the White House for the short drive across the National Mall to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. Upon their arrival at the museum, the group was escorted to the Lunar Module display, where they were greeted by Admiral Truly, Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin, and Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution Robert Adams. After a quick photo opportunity attended only by invited pool photographers, President Bush and his growing entourage were escorted to the museum’s front steps, where after a brief hold he was ushered on stage with an obligatory rendition of “Hail to the Chief.”

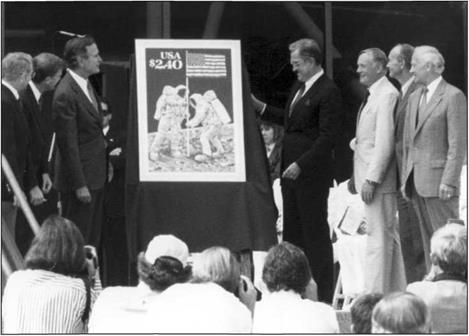

|

President Bush, Vice President Quayle, and the Apollo 11 crew (NASA Image 89 -11-382) |

The first order of business for the event was the unveiling of an Apollo 11 postage stamp by Postmaster General Anthony Franks. The $2.40 stamp depicted Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin raising the American flag on the plains of the Sea of Tranquility. After brief remarks by Truly, Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin, Vice President Quayle introduced George Bush. President Bush opened his remarks by saluting “three of the greatest heroes of this or any other century: the crew of Apollo 11.” Bush used the first several minutes of his address remembering the remarkable accomplishment of that first human landing on the lunar surface. He recounted his family’s personal recollections of the landing—his children spread throughout North America, each listened in their own way. “Within one lifetime,” the president stated, “the human race traveled from the dunes of Kitty Hawk to the dust of another world. Apollo is a monument to our nations unparalleled ability to respond swiftly and successfully to a clearly stated challenge and to America’s willingness to take great risks for great rewards. We had a challenge. We set a goal. And we achieved it.”

|

President Bush and Postmaster General Anthony Frank unveil Apollo 11 commemorative stamp (NASA Image 89-HC-394) |

Celebrating such an important legacy, Bush asserted, was an appropriate time to look to the future of the American space program. He proclaimed the inevitability of human exploration and permanent settlement of the solar system in the 21st century, in the process confirming the United Statess place as the preeminent space faring nation on Earth. Based on this rhetorical foundation, Bush unveiled his vision for this future exploration and settlement. “In 1961 it took a crisis—the space race—to speed things up. Today we don’t have a crisis; we have an opportunity. To seize this opportunity, I’m not proposing a 10-year plan like Apollo; I’m proposing a long-range, continuing commitment. First, for the coming decade, for the 1990s: Space Station Freedom, our critical next step in all our space endeavors. And next, for the new century: back to the Moon; back to the future. And this time, back to stay. And then a journey into tomorrow, a journey to another planet: a manned mission to Mars.” The President stated these missions would follow one another in a logical progression, creating a pathway to the stars. He made clear that while setting the nation on this visionary course, the primary focus of his Administration would be the completion of Space Station Freedom—a crucial stepping stone for missions beyond Earth orbit.

|

President Bush signs Space Exploration Day proclamation (NASA Image 89-HC-402). |

President Bush announced that he was tasking Vice President Quayle to “lead the National Space Council in determining specifically what’s needed for the next round of exploration: the necessary money, manpower, and materials; the feasibility of international cooperation; and develop realistic timetables—milestones—along the way.” He requested that the Space Council report its findings to him as soon as possible, with concrete recommendations regarding the proper course to the Moon, Mars, and beyond. As his remarks wound down, Bush explained the one rationale for the grand initiative by alluding to the Apollo 1 fire and the Challenger accident, stating, “there are many reasons to explore the universe, but ten very special reasons why America must never stop seeking distant frontiers; the ten courageous astronauts who made the ultimate sacrifice to further the cause of space exploration. They have taken their place in the heavens so that America can take its place in the stars. Like them, and like Columbus, we dream of distant shores we’ve not yet seen. Why the Moon? Why Mars? Because it is humanity’s destiny to strive, to seek, to find. And because it is America’s destiny to lead.” The President opined that humans would ultimately reach out to the stars and to new worlds. While he believed that this would not happen in his lifetime or that of his children, making this dream a reality for future generations must begin with a commitment by his generation. He concluded that “we cannot take the next giant leap for mankind tomorrow unless we take a single step today.”[167]

|

President Bush announces SEI on steps of National Air and Space Museum (NASA Image 89-H-380). |

Shortly after President Bush finished his remarks, Admiral Truly was introduced by Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater in the White House Briefing Room to answer questions regarding the President’s speech. Truly’s answer to the very first question of the press conference was surprising, considering he had been intimately involved with the decision-making process for SEI. Asked if there was a proposed date for the first human landing on the red planet, he replied, “no…I just, frankly, learned this morning what [President Bush’s] direction was.”[168] Following this rocky start, Truly stumbled through a series of questions regarding the specifics of the plan and the political practicality of obtaining Congressional support for such an ambitious undertaking. Asked whether the potential budget for the Moon-base portion of the President’s plan would top $100 billion, he replied somewhat lamely that it would be affordable over the long-term. When pressed on the probable cost of the endeavor, Truly admitted that “we don’t have any detailed NASA figures. We have, obviously, in the last several weeks, looked in gross terms at what it would cost, but there was no specific timetable and I have not presented the President with a specific and detailed list of budgetary requirements.”[169] The press conference continued along this shaky path with a question regarding the timetable for announcing a specific plan and budget for the initiative. Truly was once again unable (or unwilling) to provide a specific answer to this question, vaguely answering that it would take a number of months. He rallied in the end with his answer to a question regarding the necessity to bring in foreign partners, stating, “I think we can afford to go it alone, although I think that’s probably in the long run not what’s going to happen. The world has changed since the 1960s in space. It’s premature…to know where we’re heading, but I would think [SEI will] have an international flavor.”[170] In retrospect, what is most striking about this press briefing was the lack of specifics regarding the Administration’s plans to gain Congressional approval for SEI. Rapid decision – making was required to formulate the initiative in time to announce it on the Apollo 11 anniversary. Consequently, the White House did not have the time to formulate a strategy for winning support on Capitol Hill. Likewise, the Space Council had not drafted a top-level policy directive to guide administration activities aimed at further defining the initiative. In the coming months, these shortcomings would derail SEI.

As Admiral Truly’s briefing was ongoing in the pressroom, guests began assembling on the White House South Lawn for a celebration of Apollo ll’s landing on the Moon. With picnic tables spread throughout the center of the lawn and a U. S. Navy band playing in the background, the guests sat down to partake of a lunch that included barbecue pork ribs, barbecue chicken, potato salad, and deep dish apple Betty with ice cream. Among the 300 distinguished attendees were 23 Apollo astronauts, 26 key members of Congress, and dozens of NASA officials. President and Mrs. Bush arrived at noon and were seated at a table near the bandshell with a group of special guests.[171]

After lunch, President Bush walked to the stage to deliver some brief remarks to the gathered celebrants. He warmed the crowd up with a little astronaut humor, joking that planning the barbecue was hectic because he was unsure whether they preferred their food grilled or in a tube. He continued to say that “as you might

|

White House picnic celebrating Apollo 11 anniversary (NASA Image 89-H-396). |

expect from a former Navy pilot who lived much of his adult life in Houston, I, too, am a longtime supporter of the space program.” As an example of this support, he pointed to the fact that the single largest percentage increase for any agency in his Administration’s first budget proposal was for NASA. He told those assembled, “My commitment today to forge ahead with a sustained, manned exploration program, mission by mission—the space station, the Moon, Mars, and beyond—is a continuing commitment to ask new questions, to seek new answers, both in the heavens and on Earth. James Michener was right when he told Congress: ‘There are moments in history when challenges occur of such a compelling nature that to miss them is to miss the whole meaning of an epoch. Space is such a challenge,’ he said. Well, today’s announcement is our recognition that the challenge was not merely one that belonged in the sixties; it’s one that will occupy Americans for generations to come… the American people, I’m convinced, want us back in space—and this time, back in space to stay.” Bush concluded by stating that he looked forward to the day when a future president addressed, in similar fashion, the first Americans to walk on Mars, “now only children, perhaps your children.”[172]