ALEXEI LEONOV, THE FIRST MAN ON THE MOON

But what if Alexei Leonov had been the first man on the moon? The selection of Alexei Leonov as first man on the moon – and also to fly the first L-1 around the moon – is no surprise, for he was perhaps the leading personality of the cosmonaut squad after Yuri Gagarin himself [27].

Alexei Leonov was selected among the original group of cosmonauts in I960. A short, well-built man full of energy and good humour, he had demonstrated his personal qualities from his teenage years. Alexei Leonov came from Listvyanka, Siberia where he was born in 1934, only months after Yuri Gagarin. He was eighth in a family of nine. Listvyanka was so cold that temperatures fell to — 50°C, but the stars by night were so perfectly clear. When he was only three and in the middle of winter, his father Arkhip was declared an enemy of the people; neighbours came in and stripped their home bare and the family was evicted into the nighttime winter forest [28]. The family fled to his married sister’s home. Arkhip was cleared and later rejoined them there.

Most astronauts and cosmonauts will tell you that all they ever wanted to do in life was fly a plane or a spaceship. Not Alexei Leonov, who determined to be an artist, a painter. He enrolled in the Academy of Arts in Riga in 1953. But he was unable to afford it and applied for Air Force college. He flew MiG-15s from Kremenchug Air Force Base in the Ukraine and later flew planes along the border between the two Germanies. In 1959, he was asked to go for selection for testing new types of planes and when undergoing medical tests for this unspecified assignment he met his subsequent best friend, Senior Lieutenant Yuri Gagarin.

Even before his first mission, he had two brushes with death: once when his car plunged through ice into a pond (he rescued his wife and the taxi driver from under the water) and then when his parachute straps tangled with his ejector seat (he bent the frame through brute force and freed the straps). It was a surprise to no one that he was assigned an early mission and he was Korolev’s choice for the first spacewalk. To keep himself fit, in the year up to the flight he cycled 1,000 km, ran 500 km and skied 300 km. The mission, Voskhod 2, itself was full of drama. It started with triumphant success: television viewers saw him push himself away from the craft and turn head

|

Alexei Leonov’s spacewalk |

over foot as he gave an excited commentary of what must have been a stunning spectacle. He had great difficulty trying to get back into his spaceship. Only by reducing the spacesuit pressure to danger level and by using his physical strength was he able to get back into his airlock. Then the retrorockets failed to fire so he and his pilot Pavel Belyayev had to light them manually on the following orbit. Instead of landing in the steppe, they came down far off course, their communication aerials burnt away, in the Urals. State radio and television played Mozart’s Requiem, preparing the Soviet people for the worst. Their hatch jammed against a birch tree and they could barely open it. They emerged into deep snow, tapped out a morse message calling for rescuers and drew their emergency pistol to ward off prowling wolves and bears. The cosmonauts spent two nights among the fir trees while rescue crews tried to find a way of getting them out. They lit a fire to keep warm and eventually used skis to escape their ordeal. No wonder they got a hero’s welcome when they returned. Definitely the Russian right stuff.

Alexei Leonov had an artistic bent and made many paintings of orbital flight, spacewalks, sunrises and sunsets, and spaceships landing on distant worlds. He edited

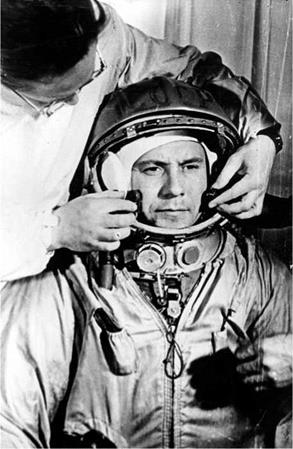

|

Alexei Leonov landed in a forest in the Urals |

the newsletter of the cosmonaut squad, called Neptune, satirizing people and events with his cartoons. He maintained an extraordinary level of physical fitness and kept up his outdoor pursuits, like water skiing and hunting. He learned English and was inevitably popular with the Western media. Unlike Gagarin and Titov, he seemed to cause the commanding officers of the cosmonaut squad little trouble. Sergei Korolev praised him for his liveliness of mind, his knowledge, sociability and character. With that background and experience, he was ideally suited for the assignment of first man on the moon and, indeed, first man around the moon before that. Certainly, had he got there, the moon landing would have been well illustrated as a result. Even from his spacewalk he had generated a substantial repertoire of paintings, books and films. Unlike Neil Armstrong, who retreated for many years into academia, the extroverted Alexei Leonov would have done much to tell of his experience thereafter.

Even though Alexei Leonov did not make it to the moon, the rest of his space career was full of incident. In June 1971, he was slated to command the second mission to the Salyut space station. His flight engineer, Valeri Kubasov, was pulled only two days before the flight because of a health problem and the entire crew was replaced, despite Leonov’s voluble protests. His comments became muted when the entire replacement crew was killed on returning to Earth: a depressurization valve opened in the vacuum instead of during the final stages of the return to Earth. He had cheated death again. In 1975, Leonov was the obvious choice for the joint Apollo-Soyuz mission. Leonov was the star of the show, a gracious host to the Americans on board Soyuz, cracking jokes and presenting the Americans with cartoons and souvenirs. The

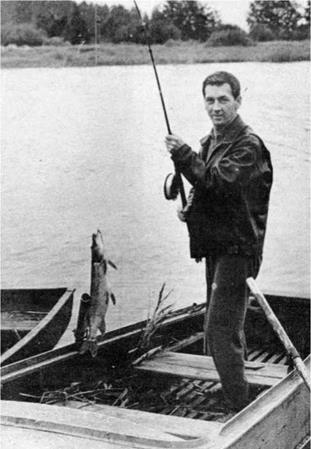

|

Alexei Leonov splashdown-training in the Black Sea |

|

Oleg Makarov |

Americans described him as ‘a really funny guy who also knows how to get us to work’. Alexei Leonov made general, was appointed commander of the cosmonaut squad from 1976 to 1982 and was a senior figure in Star Town until 1991. He still lives there, moving on to become president of one of Russia’s biggest banks.

What of his companion for both missions, Oleg Makarov? Oleg Makarov was born in the village of Udomlya, in the Kalinin region near Moscow, on 6th January 1933 into an Army family. Oleg Makarov graduated as an engineer from the Moscow Baumann Higher Technical School in 1957 and worked in OKB-1 straight after. Makarov was centrally involved in the design of the control systems for Vostok, Voskhod and Soyuz, including Vostok’s control panel. He was selected in the 1966 group of civilian engineers appointed to the cosmonaut squad by chief designer Vasili Mishin. Several members of this group were fast-tracked into mission assignments, and it shows that Mishin and the selectors must have thought much of him to appoint him straight away to the first moon crew with Leonov.

In the event, Oleg Makarov did get to fly into space a number of times. His first mission was to requalify the Soyuz after the disaster of June 1971. With Vasili Lazarev, he put the redesigned spaceship, Soyuz 12, through its paces in a two- day mission. The two were assigned to a space station mission in April 1975. This went badly wrong, the rocket booster tumbling out of control. They managed to separate their Soyuz 18 spaceship from the rogue rocket and after 400 sec of weightlessness made the steepest ballistic descent in the history of rocketry, the G meter jamming when they briefly reached 18 G. Their spacecraft tumbled into a nighttime valley on the border with China and they waited some time for rescue. Soyuz came down in snow, in temperatures of —7°C, the parachute line snagging on trees at the edge of a cliff. The Western media alleged that the cosmonauts had died, so on his

|

Valeri Bykovsky parachuting |

return Makarov was sent out to play football with them to prove he was still alive. Oleg Makarov returned to space twice more. In 1978, he participated in the first ever double link-up with a space station, Salyut 6. Oleg Makarov flew again on an uneventful two-week repair mission to Salyut 6 in a new spaceship, the Soyuz T, in 1980. He died on 28th May 2003, aged 70. His obituary duly acknowledged the role he had played in the L-1 and L-3 programmes over 1965-9. Of a quieter disposition than Leonov, his technical competence must have been very evident and he would clearly have been a good selection.

What about the second crew, Valeri Bykovsky and Nikolai Rukhavishnikov? They too were slated for the second around-the-moon mission. Valeri Bykovsky was drawn from the 1960 selection with Yuri Gagarin and was given the fifth manned space mission, Vostok 5. He flew five days in orbit, three in formation with the Soviet Union’s first women cosmonaut, Valentina Tereshkova. A quiet and confident man, the same age as Gagarin (born in 1934), he was a jet pilot and later a parachute instructor. He would often volunteer to test out training equipment and was the first person to try out the isolation chamber for a long period. Bykovsky left the moon group for a brief period to head up the Soyuz 2 mission, scheduled for launch on 24th April 1967, but cancelled when the first Soyuz got into difficulties. It took some time for Bykovsky to get another mission, not doing so until 1976, when he flew a solo Soyuz Earth observation mission (Soyuz 22) and then led a visiting mission to the Salyut 6 space station (Soyuz 31, 1978). After his last mission, he became director of the Centre of Soviet Science & Culture in what was then East Berlin.

Nikolai Rukhavishnikov was one of the best regarded designers of OKB-1. An intense, dedicated, serious-looking man, he came from Tomsk in western Siberia, where he was born in 1932. His parents were both railway surveyors, so he spent much of his youth on the move, living a campsite life. His secondary education was in Mongolia, and from 1951 to 1957 studied in the Moscow Institute for Physics and Engineering, specializing in transistors. Within a month of graduation, he had joined OKB-1, concentrating on automatic control systems. For the translunar mission, he

|

Nikolai Rukhavishnikov |

planned experiments in solar physics. When the circumlunar and landing missions were delayed, he was assigned to the Salyut space station programme, being research engineer on the first mission there, Soyuz 10. Nikolai Rukhavishnikov was next selected for the Apollo-Soyuz test project, flying the dress rehearsal mission with Anatoli Filipchenko in 1974. Nikolai Rukhavishnikov was the first civilian to be given command of a Russian space mission, Soyuz 33. This went wrong, the engine failing as it approached the Salyut 6 station. Rukhavishnikov had to steer Soyuz through a hazardous ballistic descent. ‘I was scared as hell’, he admitted later. He later contributed to the design of the Mir space station and died in 1999.

And what about the others? The third lunar landing crew was Pavel Popovich and Vitally Sevastianov. The two of them had worked closely on the Zond 4 mission, their voices being relayed to the spacecraft in transponder tests. Pavel Popovich came from the class of 1960, an Air Force pilot based in the Arctic. He made history in 1962 when his Vostok 4 took him into orbit close to Vostok 3 on the first group flight. An extrovert like Leonov, extremely popular, he had a fine tenor voice and sang his way through his time off in orbit. His first wife Marina was also well known, being an ace test pilot. Later, he was given command of Soyuz 14, making the first successful Soviet occupation of an orbital station, the Salyut 3. Later he became a senior trainer in the cosmonaut training centre. Vitally Sevastianov was a graduate of the Moscow Aviation Institute and one of the teachers of the first group of cosmonauts, specializing in celestial physics. In between his own lunar training, he ran his own television programme, a science show called Man, the Earth and the Universe. He was one of the first of the moon group to get a mission once it became clear that there would be no early flight around the moon or landing. Vitally Sevastianov was assigned to Soyuz 9 in 1970 and later got a space station mission, 63 days on board Salyut 4 in the summer of

|

Pavel Popovich |

1975, setting a Soviet record. Later, he became a leading member of the Communist Party in the Russian parliament, the Duma.

The fate of the Soviet around-the-moon and landing team makes for a number of contrasts with the American teams. For most of the American Apollo astronauts who went to the moon, the experience was the climax of their spaceflight careers and many retired from the astronaut corps soon thereafter. For the Russians, the lunar assignment was a brief period during their cosmonaut career. Although crews were named, formed and re-formed, none got close to a launch and the training experience seems to have been quite unsatisfactory. For them, the lunar assignment was short and the best of their careers was still to come. Most were quickly rotated into the manned space station programme where they went on to achieve much personal and professional success. Alexei Leonov would have made a dramatically different first man on the moon from Neil Armstrong.

|

Vitally Sevastianov |