The Fourth Decade: 1991-2000

|

STS-37 |

|

|

Int. Designation |

1991-027A |

|

Launched |

5 April 1991 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

11 April 1991 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 33, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-104 Atlantis/ET-37/SRB BI-042/SSME #1 2019; #2 2031; #3 2107 |

|

Duration |

5 days 23hrs 32 min 44 sec |

|

Call sign |

Atlantis |

|

Objective |

Deployment of the Gamma Ray Observatory (GRO), the second of NASA’s four great observatories; EVA Development Flight Experiments |

Flight Crew

NAGEL, Steven Ray, 44, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 51-G (1985); STS 61-A (1985) CAMERON, Kenneth Donald, 41, USMC, pilot GODWIN, Linda Maxine, 38, civilian, mission specialist 1 ROSS, Jerry Lynn, 43, USAF, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 61-B (1985); STS-27 (1988)

APT, Jerome “Jay”, 41, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

Atlantis left the pad almost on time with low-level clouds causing the only delay, of four minutes. Atlantis now carried newly upgraded general purpose computers. The primary payload, the Gamma Ray Observatory, was deployed during FD 3 (7 April), but its high-gain antenna failed to deploy on command. Ross (EV1) and Apt (EV2) performed an unscheduled EVA, the first since April 1985 (STS 51-D) to manually deploy the antenna, permitting the observatory to be successfully released into orbit. The two EVA astronauts had been preparing to exit the Shuttle in the event of something going wrong with the deployment, and as the GRO was lifted out of the payload bay by the RMS, they were checking out their suits. The solar panels of the GRO were opened to their full span of 21 m, although the high-gain antenna it unlatched did not deploy its 5-metre boom. As the procedures for the contingency EVA were faxed up to the crew, Ross and Apt donned their suits and prepared to exit the vehicle. Meanwhile, the crew fired the thrusters on the Shuttle to try to shake the boom loose, but without success. During the 4 hour 26 minute EVA, Ross tried to push the boom free. When that did not work, they set up a work platform to proceed with the manual deployment sequence they had practised four times in the Weightless

|

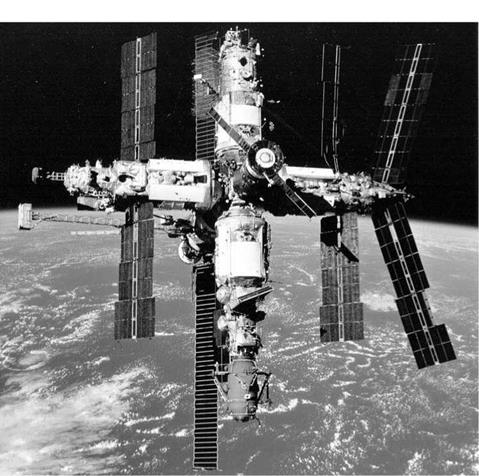

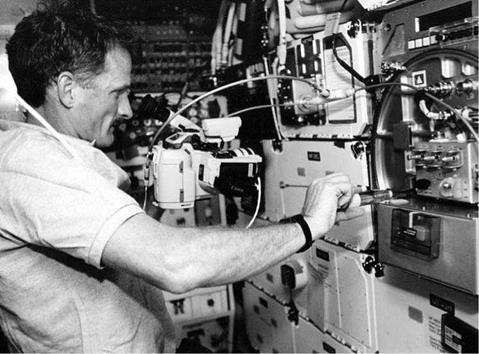

Still in the grasp of the RMS the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory is held above Jay Apt during the successful 7 April EVA to free its high-gain antenna |

Environment Training Facility, or WETF, during training. Finding adequate hand holds was a problem, especially during the night time pass of the orbit. While Apt checked to ensure they were not damaging the boom, Ross removed a locking pin and pulled the antenna boom to its deployment position, then used a wrench to lock it into position. While they were outside, they also took the opportunity to perform some of the planned EVA Development Flight Experiment activities by evaluating hand rails, measuring the forces imparted on the foot restraints during the performance of simple tasks, and performing translation exercises. When the GRO was ready for deployment they returned to the airlock, but did not re-pressurise it in case they were needed again. They watched the deployment from the vantage point of the airlock hatch.

The following day (8 April), both men were back outside for the scheduled EVA (5 hours 47 minutes). This time, the two astronauts assembled a 14.6-metre track down the port side of the payload bay and fixed the Crew and Equipment Translation Aid (CETA) cart to it. This was an evaluation of the type of cart that would be installed on the space station to aid movement over long distances, saving the astronauts’ energy. They also evaluated using the RMS out over the aft of the payload bay at varying speeds, using strain gauges to measure the slippage of the arm’s brakes. They found that RMS-based tasks took longer to perform than expected and also they found themselves suffering from the cold due to excessive EMU cooling, giving rise to concerns that the same might occur during space station construction EVAs, especially on the night-side passes. New EVA gloves that were tested proved disappointing, despite excellent results obtained on Earth. The crew also recommended that back-to-back EVAs should be avoided due to crew fatigue. During the post-flight debriefing, Apt reported that the right-hand index finger of his EVA glove had sustained an abrasion and inspections revealed that the palm bar had penetrated the glove bladder by about 1 cm. Had the palm bar come out of the glove again during EVA, it was estimated that the leakage rate would not have been sufficient to activate the secondary oxygen pack, but it was clear that more work was needed on the glove design before the more arduous EVAs planned for the space station.

With the GRO deployed and two EVAs accomplished, the crew worked on their mid-deck experiments, including testing components of the Space Station Heat Pipe Advanced Radiator Element, to better understand the fluid transfer process at work in microgravity. They also processed chemicals with the BioServa apparatus, operated the Protein Crystal Growth apparatus, and made contact with several hundred amateur radio operators across the world. Due to unacceptable winds at the primary site at Edwards in California, and bad weather at the Cape, the homecoming of Atlantis was delayed by a day from 10 April, with the crew taking the opportunity to photograph the Earth.

The Gamma Ray Observatory included four instruments that observed the electromagnetic spectrum from 30keV to 30GeV. Subsequently renamed after Dr. Arthur Folly Compton, who won the Nobel Prize in physics for his work on the scattering of high-energy photons by electrons, the observatory initially worked well, but after six months problems developed in the onboard tape recorders, with high error rates in the data. This forced NASA to use the TDRS to relay data to Earth in real time instead of storing it and downloading it later. Despite the reduction in the amount of data returned, this problem did not prevent the completion of a planned all-sky survey by November 1992. The Compton Observatory’s results have been important, but are less well known than the high-profile images from Hubble. Its studies of solar flares, pulsars, X-ray binary systems, and numerous high-energy emissions have all contributed to a better understanding of gamma ray sources in deep space. The observatory was safely de-orbited and re-entered Earth’s atmosphere on 4 June 2000, nine years after its deployment from Atlantis.

Milestones

139th manned space flight 69th US manned space flight 39th Shuttle mission 8th flight of Atlantis (OV-104)

24th US and 42nd flight with EVA operations Mission completed first decade of STS flight operations 1st US EVA since December 1985

|

Flight Crew

COATS, Michael Lloyd, 45, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 41-D (1984), STS-29 (1989)

HAMMOND Jr., Blaine Lloyd, 38, USAF, pilot HARBAUGH, Gregory Jordan, 34, civilian, mission specialist 1 McMONAGLE, Donald Ray, 38, USAF, mission specialist 2 BLUFORD, Guion, 48, USAF, mission specialist 3, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-8 (1983); STS 61-A (1985)

VEACH, Charles Lacy, 46, civilian, mission specialist 4 HIEB, Richard James, 35, civilian, mission specialist 5

Flight Log

The launch of this unclassified DoD mission was originally scheduled for 9 March, but significant cracks were discovered on all four hinges on the two ET umbilical door mechanisms during processing at Pad 39A. The stack was rolled back to the VAB on 7 March and the tank sent to the OPF for repairs. After the stack was returned to the pad on 1 April, the launch attempt scheduled for 23 April was postponed due to problems with a high-pressure oxidiser turbo-pump for SSME # 3 during pre-launch loading. After replacement and testing, launch was rescheduled again, this time to 28 April.

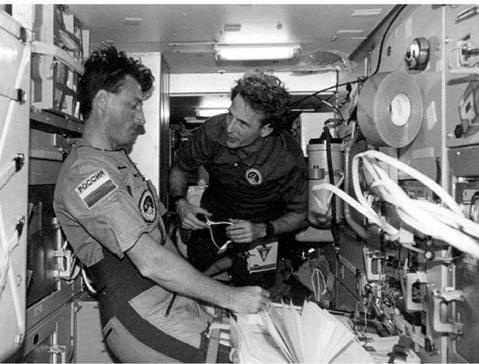

STS-39 was one of the most complicated Shuttle missions to date. The purpose of the mission was to fly an unclassified DoD programme to enhance US national security by gathering scientific data that was essential to the development of advanced missile detection systems. The crew, working a two-shift system (Red Team: Hammond, Veach, Heib; Blue Team: Harbaugh, McMongagle, Bluford – Coats working

|

This view of the payload bay of Discovery reveals some of the STS-39 payload, including the top of the STP-1 payload on the Hitchhiker carrier, and the AF-675 package comprising CIRRIS – 1A, FAR UV, HUP, QIMMS and the URA |

with either as required), also completed a variety of sophisticated experiments, including the deployment of five separate spacecraft. The Shuttle Pallet Satellite II (SPAS-II) supported both an infrared and an imaging telescope that studied the Earth’s limb, the aurora, the orbiter’s environment, and the stars both during free-flight and while attached to the RMS. Also aboard SPAS-II was the Infrared Background Signature Survey (IBSS), which was used to image and measure the spectral nature of rocket exhaust plumes by observing both firings of Discovery’s RCS from different attitudes, and the ejection of three sub-satellites deployed from canisters in the payload bay which released chemical gases. Simultaneous observations of these gas releases were made by Earth-based instruments at Vandenberg AFB in California. The other classified deployable payload was designated the Multi-Purpose Release Canister.

Space Test Payload 1 (AFP-675) comprised five instruments designed to observe the atmosphere, aurora and stars in the infrared, far ultraviolet and X-ray wavelengths. The Cryogenic Infrared Radiance Instrument for Shuttle (CIRRIS) used an infrared detector chilled by super-cold (cryogenic) liquid helium to study airglow and auroral emissions form Earth’s upper atmosphere. The coolant was used faster than anticipated, which made this experiment a priority over SPAS II/IBSS and delayed the latter by 24 hours. Mike Coats reported that passing through the auroral displays was “just like flying through a curtain of light’’. The rescheduled experiment returned

50 per cent more data than planned. STP-1 also included the FAR UV Cameras, the Uniformly Redundant Array, the Horizon UV Program and the Quadruple Ion – Neutral Mass Spectrometer. When two tape recorders failed these instruments were adversely affected, but the crew demonstrated the value of humans in space by performing a complicated bypass repair, rerouting data via an orbiter antenna and via TDRS to the ground, fulfilling the objectives for these experiments.

The crew also took advantage of their orbital inclination to take colour and infrared pictures of important surface features and phenomena on Earth, including Lake Baikal in Russia, oil field fires in Kuwait, and the results of a devastating typhoon in the Indian Ocean and fires in Central America, whose smoke palls had drifted over Texas and as far east as Florida. The crew landed at the SLF in Florida due to unacceptably high winds at Edwards AFB.

Milestones

140th manned space flight

70th US manned space flight

40th Shuttle mission

12th mission of OV-103 Discovery

8th DoD Shuttle mission

1st unclassified DoD Shuttle mission

1st flight crew to comprise 7 NASA astronauts

STS-53 |

|

Int. Designation |

1992-086A |

|

Launched |

2 December 1992 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

9 December 1992 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 22, Edwards AFB, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-103 Discovery/ET-49/SRB BI-055/SSME #1 2024; #2 2012; #3 2017 |

|

Duration |

7 days 7 hrs 19 min 47 sec |

|

Call sign |

Discovery |

|

Objective |

Deployment of classified DoD payload (DOD-1); operation of two secondary and nine mid-deck experiments |

Flight Crew

WALKER, David Mathiesan, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 51-A (1984); STS-30 (1989)

CABANA, Robert Donald, USMC, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-41 (1990)

BLUFORD Jr., Guion Stewart, USAF, mission specialist 1, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-8 (1983); STS 61-A (1985); STS-39 (1991)

VOSS, James Shelton, US Army, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-44 (1991)

CLIFFORD, Michael Richard Uram, US Army, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

STS-53 was Discovery’s 15th mission, its first since STS-42 the previous year. During the intervening 23 months, 78 major modifications had been made to the orbiter while still at KSC. These included the addition of a drag parachute for landing and the capability of redundant nose wheel steering. The launch was delayed by one hour 25 minutes to allow the sunlight to melt ice on the ET that had accumulated thanks to overnight temperatures of —4°C.

The initial activity after reaching orbit was the deployment of a military satellite on FD 1. The satellite remains classified, although the payload was later identified as the third Advanced Satellite Data Systems Intelligence Relay Satellite. Once that deployment had been completed, the remainder of the mission became declassified. The crew continued with their experiment programme of two cargo bay and nine middeck experiments, most of which were instigated by the Defense Department Space Test Program Office, headquartered at Los Angeles AFB in California.

The experiment payload on Discovery included the Shuttle Glow Experiment/ Cryogenic Heat Pipe Experiment, which measured and recorded electrically charged

|

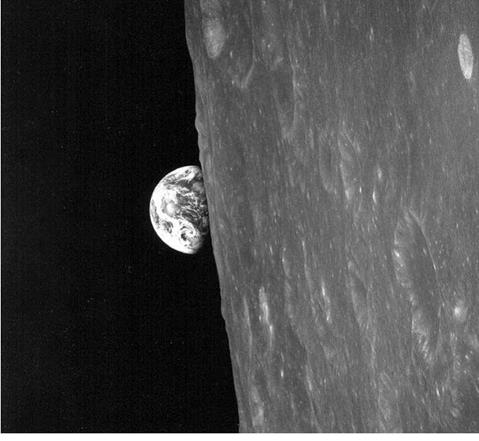

The end of one phase of Shuttle operations as Discovery lands on Runway 22 at Edwards AFB, signalling the final flight of dedicated DoD Shuttle missions. Almost eight years earlier in January 1985, the Discovery orbiter completed the first dedicated DoD mission STS 51-C landing at Kennedy |

particles as they struck the tail of the orbiter. The second part of this experiment provided research into the use of super-cold LO pipelines for spacecraft cooling. Also in the payload bay was the NASA Orbital Debris Radar Calibration Spheres (ODERACS) experiment, designed to improve the accuracy of ground-based radars in detection, identification and tracking of orbital space debris. In the mid-deck, the Microcapsule in Space and Space Tissue Loss experiments were devoted to medical research, while the Vision Function Test measured the changes in astronauts’ vision that might occur in the microgravity environment. The Cosmic Radiation Effects and Activation Monitor (CREAM) recorded levels of radiation inside the mid-deck, as did the Radiation Monitoring Experiment. There was a joint USN, US Army and NASA experiment for the crew to locate 25 preselected ground sites with a one nautical mile accuracy. This was an evaluation of detecting laser beams from space and the use of such beams in ground-to-spacecraft communications. Other experiments included a photographic assessment of cloud fields for DoD systems, while the Fluid Acquisition and Resupply Experiment studied the motion of liquids in microgravity during simulated refuelling of propellant tanks with distilled water. There were also seven medical tests, including a re-flight of the rowing machine rather than the treadmill for physical exercise.

This crew dubbed themselves “the Dogs of War Crew’’, as they represented all four branches of the US armed forces. Their training team had been called “Bad Dog’’

and these combined to have the STS-53 crew become known as the “Dog Crew” (and they often quipped that they were “working like dogs” throughout their mission). Walker was known as “Red Dog”, Cabana was known as “Mighty Dog” and Clifford, being the rookie, was known as “Puppy Dog”. Bluford became “Dog Gone” and Voss became “Dog Face”. The crew mascot was known as “Duty Dog” and a stowaway that looked over the crew during the mission (a rubber dog mask hung over an orange launch and entry suit) was known as “Dog Breath”.

The landing was originally scheduled for KSC but was diverted to Edwards due to clouds in the vicinity of the SLF. Following the landing, a small leak was detected in the forward thrusters, delaying the egress of the crew until fans and winds dissipated the leaking gas.

Milestones

156th manned space flight

82nd US manned space flight

52nd Shuttle mission

15th flight of Discovery

10th and final dedicated DoD Shuttle mission

None – sub-orbital flight 5 May 1961

None – sub-orbital flight 5 May 1961