STS-49

|

Int. Designation |

1992-026A |

|

Launched |

7 May 1992 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

16 May 1992 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 22, Edwards AFB, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-105 Endeavour/ET-43/SRB BI-050/SSME #1 2030; #2 2015; #3 2017 |

|

Duration |

8 days 21 hrs 17 min 38 sec |

|

Call sign |

Endeavour |

|

Objective |

Capture, repair and redeployment of stranded satellite INTELSAT VI (F-3); Assembly of Space Station by EVA Methods demonstration (ASSEM) |

Flight Crew

BRANDENSTEIN, Daniel Charles, 49, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-8 (1983); STS 51-G (1985); STS-32 (1990)

CHILTON, Kevin Patrick, 36, USAF, pilot

HIEB, Richard James, 36, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-39 (1991)

MELNICK, Bruce Edward, 42, US Coast Guard, mission specialist 2,

2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-41 (1990)

THUOT, Pierre Joseph, 36, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-36 (1990)

THORNTON, Kathryn Cordell Ryan, 39, civilian, mission specialist 4, EV3, 2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-33 (1989)

AKERS, Thomas Dale, 40, USAF, mission specialist 5, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-41 (1990)

Flight Log

The maiden flight of the Endeavour (the replacement orbiter for Challenger which was lost in the 1986 launch accident) was an impressive mission that clearly demonstrated the value of having astronauts on board to overcome technical problems. Whether there was a need for Endeavour itself was a question long debated, but it was the loss of Challenger that finally secured the construction of the new vehicle from the structural spares that had been factored into the orbiter construction programme several years before. There was no such contingency to replace Columbia seventeen years later.

|

|

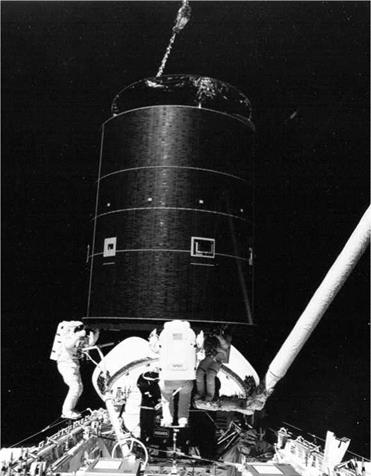

Three astronauts hold onto the 4.5-ton Intelsat VI satellite after completing a six-handed “capture”. L to r are astronauts Hieb, Akers and Thuot, who stands on the end of the RMS. This first three-person EVA was the third attempt at grappling the satellite

Following the 6 April 1992 flight readiness firing of Endeavour’s three main engines, the management team decided to replace all three due to irregularities that had arisen in two of the high-pressure oxidiser turbo-pumps. The launch of STS-49 was set for 4 May, but was rescheduled for 7 May, with an early launch window that would offer better lighting conditions for photo-documentation of the behaviour of the new vehicle during its first ascent. The lift-off on 7 May was delayed by 34 minutes due to bad weather at the transoceanic abort landing site, as well as technical problems with one of Endeavour’s master event controllers.

The primary objective of the flight was the capture and redeployment of the Intelsat VI satellite that had been launched aboard a Titan rocket on 14 March 1990.

During the launch, the second stage of the Titan had not separated, preventing the satellite’s ascent into a geosynchronous orbit. Quick thinking by ground controllers triggered the separation of the satellite from the unused Perigee Kick Motor (PKM) that was still attached to the Titan stage, and careful use of onboard liquid propellant allowed the satellite to reach a thermally stable 299 x 309 nautical mile orbit. Subsequent data analysis suggested it would be more cost-effective to bring a new kick motor up to the stranded satellite on the Shuttle than to return it to the ground and relaunch it. The Hughes Aircraft Company’s Space and Communications Group worked with NASA to construct special hardware to support the EVA operations that would be required.

The crew split into two EVA teams. Thuot (EV1) and Hieb (EV2) were termed the Intelsat EVA crew for the satellite retrieval and redeployment, while Thornton (EV3) and Akers (EV4) would work on the planned evaluation of space station construction techniques. A specially designed capture bar would be used to capture the satellite but in the event, this did not work as planned. During the first attempt on 10 May, Thuot had been unable to attach the capture bar, causing the satellite to bounce away and tumble at even greater rates the more he tried. The following day, the rotation of the satellite had slowed sufficiently for Thuot to gently move the bar into place. This time, however, the latches on the bar failed to fire, causing the satellite to drift off once again. It became evident that the planned method of capture would not work and during 11 May, as the crew rested, plans were formulated for another attempt. This would be the last chance, as Endeavour had only enough propellant aboard to support one more rendezvous. The following day, the crew practised getting three pressure – suited astronauts into an airlock that was designed to accommodate just two. Other astronauts simulated the operation in the water tank at JSC and the crew played an important role in the final decision to try the first three-person EVA.

On 13 March, Thuot, Hieb and Akers ventured outside and placed themselves in foot restraints 120° apart around the payload bay. Hieb was stationed on the starboard wall of the bay and Akers stood on a borrowed strut from the ASSEM experiment, while Thuot rode the RMS. Brandenstein and Chilton flew Endeavour and gently closed in on the satellite, allowing all three EVA astronauts to reach up and grasp the satellite by the three electric motors that would deploy the satellite’s cylindrical solar panel. Over a difficult 85 minutes, the capture bar was finally attached to the satellite, allowing the RMS to manipulate it over the payload bay and onto the new kick motor. Thuot and Hieb then used hand-operated ratchets to pull the satellite down and latch it into place with four clamps. They then connected two electrical umbilicals. With the astronauts back in the airlock, but with an open hatch in case they were still required, the new PKM was ejected from the payload bay. Thirteen minutes later, a procedural error on the checklist prevented the initial deployment. The EVA set a new duration record, surpassing that of the Apollo 17 astronauts on the Moon in December 1972. The new engine worked perfectly on 14 May, placing the satellite on its way to geosynchronous orbit.

The same day, Thornton and Akers were in the payload bay performing the ASSEM EVA demonstration. Originally scheduled for two EVAs, the Intelsat difficulty had curtailed this to a single excursion. The pair assembled a pyramid out of struts to simulate a station truss section, then attached a triangular pallet to this to simulate the mass of a major component such as a propulsion module. Scheduled for three hours, the astronauts found that it took twice as long as expected and proved very tiring, forcing other activities planned for this EVA to be cancelled. The mission had been extended by two days to complete its primary objectives and this took a toll on the crew. They also had to complete the rest of their experiment programme, including the Commercial Proton Crystal Growth experiment, the UV Plume Instrument experiment and the USAF Maui Optical Site experiment. Post-flight inspections revealed negligible damage and the crew and flight controllers reported only minor problems. The new vehicle had joined the fleet in style.

Milestones

150th manned space flight 77th US manned space flight 47th Shuttle mission 1st flight of Endeavour

25th US and 46th flight with EVA operations 1st Shuttle mission to feature four EVAs 1st use of landing drag parachute 1st three-person EVA

1st astronaut attachment of rocket motor to orbiting satellite