1997-039A 7 August 1997 1997-039A 7 August 1997

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 19 August 1997

Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida

OV-103 Discovery/ET-87/SRB BI-089/SSME #1 2041;

#2 2039; #3 2042

11 days 20hrs 26 min 59 sec

Discovery

CRISTA-SPAS-02 operations

Flight Crew

BROWN Jr., Curtis Lee, 41, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-66 (1994); STS-77 (1996)

ROMINGER, Kent Vernon, 41, USN, pilot, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-73 (1995); STS-80 (1996)

DAVIS, Jan, 43, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-60 (1994)

CURBEAM Jr., Robert Lee, 35, USN, mission specialist 2 ROBINSON, Stephen Kern, 41, civilian, mission specialist 3 TRYGGVASON, Bjarni Vladimir, 52, civilian, Canadian payload specialist 1

Flight Log

Continuing the Mission to Planet Earth programme, as well as preparations for the construction of ISS, the STS-85 mission featured a complex payload from Germany, Japan and the US, as well as an international crew.

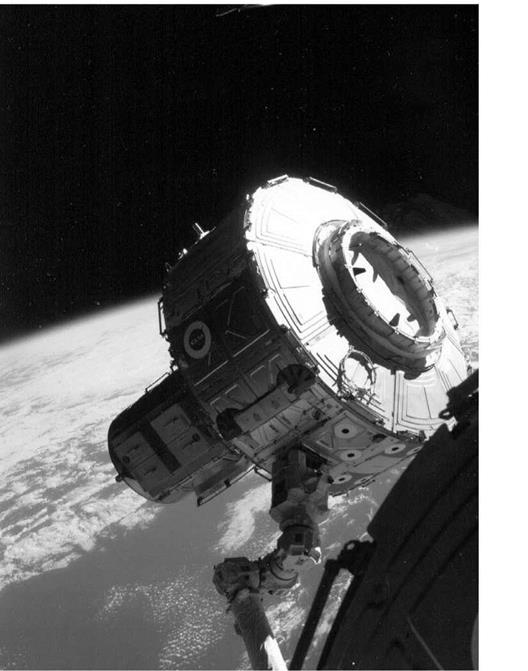

The primary payload on this flight was the Cryogenic IR Spectrometer and Telescope for the Atmosphere Shuttle Pallet Satellite-2 (CRISTA-SPAS-2), making its second flight on the Shuttle as part of the fourth cooperative mission between the German space agency DARA and NASA. There were three telescopes and four spectrometers on the satellite. Deployed on FD 1, it operated for over 200 hours and was retrieved on FD 10. After completing its primary objective, CRISTA-SPAS was used in a simulation exercise to prepare for the first ISS assembly flight, STS-88, with the payload being manipulated as if it were the Russian Functional Cargo Block (FGB-Zarya) that was to be attached to the US Node 1 (Unity).

The Technology Applications and Science 01 (TAS-01) payload included seven separate experiments to gather data on the topography of the Earth and its atmosphere, to study the energy from the Sun and to evaluate new thermal control devices. International Extreme UV Hitchhiker 02 was a set of four experiments that studied

|

Canadian astronaut Bjarni Tryggvason inputs data into a computer for the Microgravity Vibration Isolation Mount (MIM) experiment located on the mid-deck of Discovery. Behind him, the use of mid-deck lockers for stowage both inside and outside is evident

|

UV radiation from stars, the Sun and other solar system sources. The Japanese Manipulator Flight Demonstrator (MFD) consisted of three separate experiments located on a support structure in the payload bay and were designed to test a mechanical arm that was being evaluated for possible inclusion on the Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) planned for ISS. Despite some glitches, a series of exercises was performed by the crew in space and a team of operators on the ground.

There was also a range of in-cabin payloads, including a UV imaging system to observe Comet Hale-Bopp, crystal growth and materials-processing experiments, the Orbiter Space Vision System (to be used during ISS assembly for determining precise alignment and pointing capability). Canadian astronaut Bjarni Tryggvason, principle investigator of the Microgravity Vibration Isolation Mount (MIM), had a major role on the flight in evaluating his own equipment, performing fluid physics experiments to determine sensitivity to spacecraft vibrations when using MIM, and its application to ISS and future research facilities. The MIM had been in operation aboard Mir since April 1996 and was first operated by Shannon Lucid, where it supported a number of Canadian and US experiments in materials science and fluid physics.

The 18 August landing opportunities were waived off due to ground fog in the local area, allowing the crew an extra day on orbit.

Milestones

201st manned space flight 116th US manned space flight 86th Shuttle mission 23rd flight of Discovery

Flight Crew

MUSABAYEV, Talgat Amangeldyevich, 50, Russian Air Force, commander, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM19 (1994); Soyuz TM27 (1998)

BATURIN, Yuri Mikhailovich, 51, Russian political aide, flight engineer,

2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM28 (1998)

TITO, Dennis, 60, civilian, US space flight participant

Flight Log

Soyuz TM32 was scheduled to be the mission that exchanged the Soyuz (TM31) that had carried the first resident crew to the station six months before. The mission was also known as Taxi-1. However, just to confuse things, the Russians decided to rename these missions (and the Progress flights) by order of flight sequence to the new station. So Soyuz TM31 became Soyuz 1 (the original of which actually flew in 1967) and the first Progress (M1-3) became Progress 1 (which originally flew in 1978). Soyuz visiting missions had been conducted for some time with their own space stations, with Russian cosmonaut crews exchanging the Soyuz craft every six months at the end of the vehicle’s “shelf-life”. Beginning with ISS-2, main crews for the new station would be launched and landed on the Shuttle, though all crews would be trained on Soyuz entry and landing procedures, at least for the foreseeable future as the station was being constructed. The crew would include one experienced commander, one rookie flight engineer and, since Soyuz carried a third seat, the opportunity to fly a second Russian or international cosmonaut to ISS. Russia also quickly realised that this was a seat worth selling. The idea of flying fare-paying passengers on short visiting missions became a possibility near the end of the Mir programme, but that station was de-orbited before a “space tourist’’, or space flight participant (SFP) had the chance to pay the US$20 million price tag for the privilege. With ISS, the opportunity for such flights was once again available.

|

The first “space tourist”, Dennis Tito (left), is safely back on Earth after his $20 million flight into space. Musabayev (centre) and Baturin are shown with him, having exchanged the TM31 craft for the fresher TM32

|

NASA was not happy about less than fully trained crew members flying to the ISS. As the station was under construction, there was the concern about the tourist endangering the resident crew or affecting the smooth operation of the mission. However, as the Russians were flying the passenger, NASA had no veto over the decision. Instead, they did try to curtail such tourists’ station access to the Russian elements only. The first to fly in this way was American businessman and millionaire Dennis Tito, who had been planning a trip to Mir and was offered a ride to ISS to compensate.

After much media coverage, the TM32 crew arrived at ISS at the nadir port of Zarya. Though TV views of the crew transfer to the station were received, NASA indicated that only Russian-supplied images would be available, not theirs. The short programme of the Kristall crew included Earth observations, a seed and biology experiment, a food digestive experiment, crystal experiments and “commemorative activities”. On board the station, the Taxi crew were called cosmonaut researchers 1 (Musabayev), 2 (Baturin) and 3 (Tito). Tito also used video and still cameras to record activities on board the station. In a Russian press conference, Tito mentioned that he had indeed visited the US segment several times. Despite reports that he suffered from space sickness, Tito indicated that he “liked space.’’ Both Musabayev and Usachev reported that Tito had not hindered the work of the main crew and had assisted in meal preparations. Voss and Helms were advised by NASA to keep their activities with Tito to formal participation. In light of the visit of Tito, NASA amended its procedures for approving visiting “tourists” to ISS. Future visitors would now have to participate in basic safety and awareness training at JSC, and those “tourists” who followed Tito would have to develop a stronger scientific programme to occupy them during their week on the ISS.

The crew came home in the TM31 spacecraft on 6 May. A faulty infrared vertical sensor reportedly caused them to overshoot their landing site by 56 km. The landing was a hard one, so hard that Musabayev had to check whether his $20 million passenger was still alive! The mission certainly generated further interest in “Soyuz seats for sale” and provided the possibility of short visiting missions to ISS to exchange the Soyuz and, while there, conduct small science programmes that would not interrupt the main work of the resident crew. This was the continuation of the Interkosmos programme that the Russians had developed over 20 years before.

Milestones

225th manned space flight 91st Russian manned space flight 84th manned Soyuz mission 31st manned Soyuz TM mission 2nd Soyuz ISS ferry mission 1st Soyuz visiting mission 1st space flight participant (Tito)

Flight Crew

LINDSEY, Steven Wayne, 40, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-87 (1997); STS-95 (1998)

HOBAUGH, Charles Owen, 39, USMC, pilot

GERNHARDT, Michael Landen, 44, civilian, mission specialist 1, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-69 (1995); STS-83 (1997); STS-94 (1997)

REILLY II, James Francis, 47, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-89 (1998)

KAVANDI, Janet Lynn, 42, civilian, mission specialist 3, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-91 (1998); STS-99 (2000)

Flight Log

This mission completed the second phase of ISS assembly by providing an airlock facility that would allow EVAs to be conducted from the station without the need for a Shuttle to be docked to it. Atlantis docked with ISS on 13 July and would remain there for the next 196 hours. The mission’s three EVAs supported the installation of the Joint Airlock module (called Quest) on the station.

The first EVA (14 Jul for 5 hours 59 minutes) saw Gernhardt (EV1) and Reilly (EV2) remove insulation covers from berthing mechanisms on the airlock and install bars to what would be the attachment points for the four high pressure gas tanks. Using Canadarm2, ISS-2 crew member Susan Helms then lifted the airlock out of the payload bay of Atlantis and installed it on the right side of Unity. The EVA crew then attached heating cables from the station to the airlock and positioned foot restraints to support future EVAs. Three days later (17 Jul for 6 hours 29 minutes), the EVA crew returned to Quest to install the three tank assemblies on the airlock with the help of both the station and Shuttle robotic arm systems. The final EVA four days later (21 Jul for 4 hours 2 minutes) was the first out of the Quest airlock. During the

|

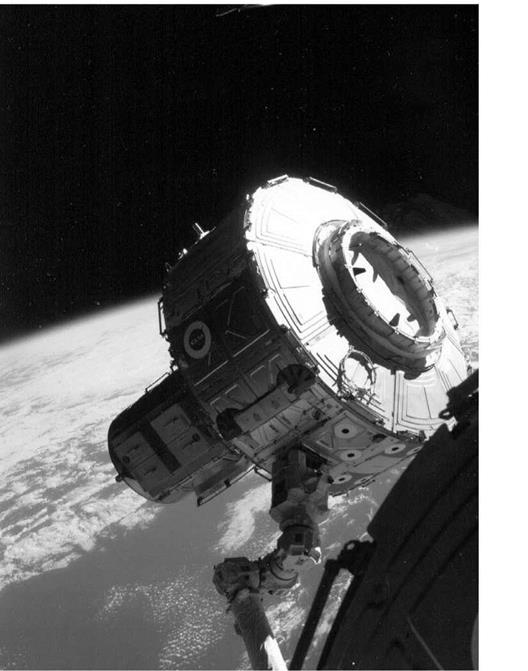

|

The Quest airlock is in the process of being installed onto the starboard side of Unity Node 1 of ISS. The airlock, delivered by STS-104, is being moved by ISS-2 FE Susan Helms using the SSRMS Canadarm2 from a control panel located in the US Destiny laboratory excursion, the EVA crew installed further tank assemblies on the outside of the station, again with the help of both RMS systems. In the days between each EVA, nitrogen and oxygen lines were tested and valves installed inside the facility to connect Quest to the ISS ECLSS. A computer was also installed to manage the airlock systems. Air bubbles in a coolant line caused a water spill and its clean-up postponed other activities for a day. A leaky air circulation valve was replaced and the hatch was relocated from its initial location between the airlock and the Unity Node hatch to become an inner EVA hatch between the equipment lock (storage and servicing of EVA equipment) and the crew lock (access to open space). A dry run using the Quest systems was performed prior to formal inauguration on 21 July, just hours after the 32nd anniversary of the first lunar EVA on Apollo 11 on 20 July 1969.

Undocking from ISS occurred in the early hours of 22 July, and after a 24-hour waive-off due to weather conditions in Florida, Atlantis achieved a night time landing back at the Cape the following day. Between July 2000 and the arrival of Quest, over 69,853 kg of hardware had been added to the station. This included the Zvezda module, the Z1 Truss (STS-92), PMA-3 (STS-92), the P6 assembly and solar arrays (STS-97), the US Destiny lab (STS-98), Canadarm2 (STS-100) and now Quest (STS – 104). This would allow the station to conduct independent operations. Though future assembly missions and re-supply missions would still be required, the crews on board the station could now conduct expanded programmes of science and station-based EVAs, as well as routine maintenance and housekeeping duties.

Milestones

226th manned space flight 135th US manned space flight 105th Shuttle mission 24th flight of Atlantis

49th US and 82nd flight with EVA operations 10th Shuttle ISS mission 4th Atlantis ISS mission 1st EVA from Quest airlock

Flight Crew

KRIKALEV, Sergei Konstaninovich, 46, civilian, Russian ISS-11 and Soyuz commander, 6th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM7 (1988); Soyuz TM12 (1991); STS-60 (1994); STS-88 (1998); ISS-1 (2000/01)

PHILLIPS, John Lynch, 54, civilian, US ISS-11 science officer, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-100 (2001)

VITTORI, Roberto, 40, Italian Air Force, Soyuz flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM34 (2002)

Flight Log

The eleventh residency aboard ISS would be the first to receive a Shuttle mission since STS-113 in December 2002. The loss of Columbia and her crew had created the need to fly two-man resident crews, termed caretakers, because orbital operations were restricted by the availability of onboard supplies, and station expansion curtailed by the grounding of the Shuttle. This was the fifth such caretaker crew, but the docking of STS-114 in July signified that full station operations could soon be resumed.

Flying to the station with EO-11 was ESA astronaut Vittori, who completed 23 experiments in 91 sessions under the Eneide programme. His research consisted of studies in human physiology, biology, demonstrations of new technology and a programme of education demonstrations. Vittori would also participate in a number of ceremonial and public relations broadcasts, a feature of most crew exchanges and international missions in space. Vittori would return to Earth aboard TMA5 along with the two ISS-10 crew members.

Almost as soon as the new crew were left alone on the station, their time was taken up by problems with the Elektron system, which finally broke down in early May.

|

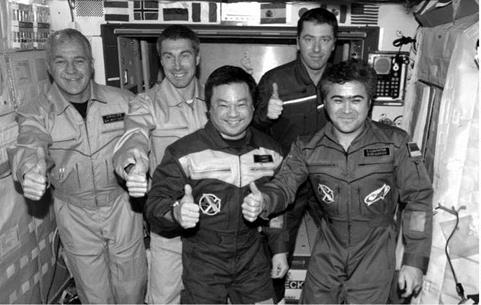

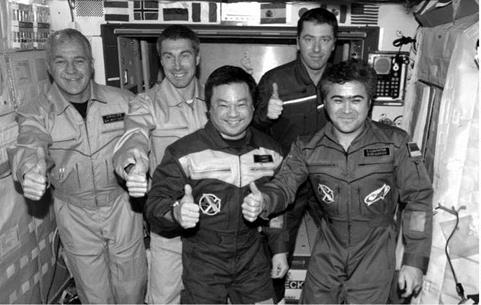

Change of shift on ISS. The ISS-10 and 11 crews give the thumbs-up to the continuation of manned station operations. L to r John Phillips and Sergey Krikalev (ISS-11), Leroy Chiao (ISS-10), Italian Roberto Vittori (ESA) and Salizhan Sharipov (ISS-10)

|

There were sufficient alternative oxygen supplies aboard the station to keep the crew supplied until the end of the year, with re-supply by the Shuttle and Progress, but it was still disconcerting as troubleshooting on the unit would be added to an already heavy work programme. Other maintenance included work on the treadmill vibration isolation system. The crew received their first re-supply craft (Progress M53) in June, which delivered 2,383 kg of cargo. This included 111 kg of oxygen and 420 kg of water, as well as 40 solid fuel oxygen generation cartridges and spare parts for the Elektron unit.

The crew also completed a range of science studies, including Earth observations, medical experiments, and microgravity research. In addition they tested new software that had been installed to support the Canadarm2 unit on the station and relocated their Soyuz from the Pirs module to the Zarya module on 19 July, freeing the docking compartment for their EVA the following month. The re-docking operation took approximately 30 minutes to complete. During these relocation manoeuvres, the station had to be prepared for autonomous flight, in case the Soyuz failed to re-dock and the crew were forced to return to Earth.

On 28 July, the STS-114 crew docked Discovery with the station, bringing much – welcomed supplies and visitors to the crew, and confidence in the resumption of Shuttle ISS assembly flights. In August, the Russian Vodzukh carbon dioxide removal system failed and while the Russian ground controllers investigated the problem and came up with a repair plan, the American unit in Destiny was activated to take over the operation. On 16 August Krikalev surpassed Sergei Avdeyev’s career record of time logged in space (747 days 14 hours 14 minutes 11 seconds).

The two men performed their only EVA on 17 August (4 hours 57 minutes). For Phillips, it was the first excursion outside a spacecraft in space, but for veteran Krikalev, this was his eighth EVA. Their tasks included retrieving exterior sample cassettes, installing a new reserve TV camera for ATV dockings, and photographing exterior experiments and surfaces. Some of the activities planned for the EVA could not be accomplished due to lack of time and would be rescheduled for later crews. Following their EVA, the crew cleaned their equipment and resumed their scientific and maintenance work in preparation for their next visitors, the crew of Soyuz TMA7 and the third space flight participant. In their final days in orbit, the two men began packing up their research results, increased their exercise programme in preparation for the return to gravity and checked the systems of Soyuz TMA6. They would return to Earth with space flight participant Greg Olsen after he completed his week aboard the station.

During the descent of TMA6, there was a small pressure leak from the DM, which was noted before the undocking from ISS. An obstruction of some kind seemed to have prevented the air tight seal of the forward DM hatch into the OM. On module separation the leak continued to vent, although the crew were protected in their Sokol suits. The landing occurred successfully but Phillips had to be given smelling salts to prevent him drifting into unconsciousness. The astronaut later explained that he was far more uncomfortable in the DM than he had been in the Shuttle he had returned on in 2001. He was not sure if he became unconscious for a short time, but he knew his head was spinning. In images from the recovery operation, he certainly looked weak and pale.

Milestones

243rd manned space flight

99th Russian manned space flight

92nd manned Soyuz mission

6th manned Soyuz TMA mission

39th Russian and 93rd flight with EVA operations

10th ISS Soyuz mission (9S)

8th visiting mission (VC-7)

5th resident caretaker ISS crew (2 person)

Phillips is launched on his 54th birthday (15 Apr)

Krikalev celebrates his 47th birthday in space (27 Aug)

Krikalev sets a new cumulative record of 803 days 9hrs 39 mins in space, on six missions

1st cosmonaut to fly six missions (Krikalev)

1st person to conduct a second residence aboard ISS (Krikalev)

The first rockets to fly into space flew simple “up and down” ballistic flights to high altitude, but did not reach the velocity or height to enter Earth orbit. Many were used for science missions in the upper atmosphere (starting in the 1940s) and often carried animals. The payloads were usually, but not always, recovered. These trajectories gave engineers the opportunity to put their equipment though the stresses of launch, reentry and recovery without committing it to orbital flight. The first two Americans in space in 1961 flew this type of trajectory, although the Russians abandoned their suborbital programme in order to place the first person in orbit ahead of the Americans.

Flight paths

In order to save fuel and weight, the rotation of the Earth is used to give any launch a speed boost. Therefore, most launch sites are situated on or as close as possible to the equator to take maximum advantage of this and launch their spacecraft into a west-to – east trajectory. An east-to-west launch is possible, but it would be very expensive in terms of launch weight and fuel, and therefore cost. A rocket reaching a speed of approximately 29,000 kph (18,000 mph) can overcome the effects of Earth’s gravity pulling it back to the ground and enter an arc around the planet, known as an orbit. Strictly speaking of course, an orbiting spacecraft is still falling towards the Earth – it’s just travelling fast enough to keep missing it. There are many types of orbits, and all crewed flights to date have entered relatively low altitude Earth orbit, even if they have later further boosted their speed in order to head out into deeper space. An orbit has a high and low point, known respectively as the apogee and perigee, and an orbit with a very high apogee is known as a highly elliptical orbit.

Satellites are launched into different inclinations, or angles to the equator. A polar orbit flies approximately over the north and south poles, effectively at almost a 90- degree inclination. Most orbits feature inclinations that are much lower than this. Geostationary, or geosynchronous, orbiting satellites orbit around the equator at approximately 35,000 km (22,000 miles) and travel at the same speed as the Earth rotates, giving the perception of being “stationary” in the sky as seen by an observer. Such orbits are mainly used by communications and weather satellites. All crewed vehicles have so far been placed in relatively low-altitude and low-inclination Earth orbits, although there was a proposal to fly an Apollo mission into a highly elliptical Earth orbit and plans for polar-orbiting Shuttle missions were abandoned in 1986.

|

An illustration of the options that Apollo could use to reach the Moon: (left) Direct Ascent; (centre) Earth Orbital Rendezvous, or EOR; (right) Lunar Orbital Rendezvous, or LOR – the method eventually chosen.

|

The Apollo lunar flights (1968-1972) used low-Earth parking orbits before heading out towards the Moon, using an additional engine burn of the upper stage to begin their trans-lunar trajectory. Once at the Moon, the spacecraft could either fly once around the Moon and back to the Earth (called a circumlunar trajectory – this was used for Soviet unmanned Zond missions which were precursors of planned but unflown manned missions), or orbit the Moon or land on it. The original flight plans for US manned lunar landings included several options: A direct ascent to the Moon surface using a powerful booster, joining two craft together in Earth orbit before flying out to the Moon, or a lunar orbit rendezvous (which was the method chosen for Apollo) with the Command Service Module (CSM) and two-stage Lunar Module (LM) flying together on one booster. After the Moon landing expedition was over, the ascent stage of the LM rendezvoused with the CSM in lunar orbit, the crew transferred between vehicles and the CSM headed home for parachute landing in the ocean. The new plans for the return to the Moon resemble aspects of the Earth Orbital Rendezvous method that was considered for Apollo.

Following Apollo 1, all manned space flights which attempted orbital flight succeeded in doing so up to 1975 and the aborted launch of Soyuz 18A (this mission exceeded 192km and since it is recorded as a “space mission”, it is detailed in the main log section). However, space flight is not without risk and two Soviet missions ended in tragedy and one Apollo lunar mission almost claimed the lives of the crew. In April 1967, the maiden manned flight of Soyuz ended in the tragic loss of its sole cosmonaut, Vladimir Komarov, after a difficult flight. In June 1971, the three Soyuz 11 cosmonauts died during the entry and landing phase after completing a successful 23-day mission to Salyut 1 – the first space station. In April 1970, an onboard explosion in the Service Module of Apollo 13 en route to the Moon caused the landing to be aborted as the mission became a fight to keep the crew alive and return them to Earth. The struggles and ingenuity of the crew, in conjunction with the sterling efforts of controllers and contractors and the support of their families, has become part of space folklore. These three missions can also be found in the main log. There was, however, another mission that was supposed to carry its crew into space in 1983, but it failed to even get off the ground – at least, not in the way the crew had expected to.

|

SOYUZ T10-1

|

|

|

Int. Designation

|

None – pad abort seconds prior to launch

|

|

Launched

|

Planned 27 September 1983

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 1, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan

|

|

Landed

|

Planned for late December 1983

|

|

Landing Site

|

Planned for Kazakhstan

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

R7 (Soyuz U); spacecraft serial number 16L

|

|

Duration

|

Planned for about 90 days (abort duration was 5 min 13 sec)

|

|

Callsign

|

Okean (Ocean)

|

|

Objective

|

Replace T9 crew on Salyut 7 to complete their original Soyuz T8 three-month resident programme with two EVAs to install additional solar array panels

|

Flight Crew

TITOV, Vladimir Grigoryevich, 36, Soviet Air Force, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission. Soyuz T8 (1983)

STREKALOV, Gennady Mikhailovich, 43, civilian, flight engineer, 3rd mission Previous missions. Soyuz T3 (1980); Soyuz T8 (1983)

Flight Log

Fresh from their Soyuz T8 abortive docking attempt with Salyut the previous April, Vladimir Titov and Gennady Strekalov were paired for a possible long-duration mission later in the year, swapping with Soyuz T9’s Lyakhov and Aleksandrov. When Salyut 7 began to malfunction, the Soyuz T10 mission started to take on a repair status, with Titov and Strekalov trained to perform a spacewalk to place new solar panels on the outside of the station. At 01: 36 hours local time at Baikonur, the countdown of the Soyuz rocket reached T — 80 seconds and all seemed to be normal. A valve within the propellant valve failed to close and the base of the booster caught fire. Gradually a large fire rose up the side of the booster and a massive explosion was imminent.

The Soyuz T abort system was damaged by the fire, however, and it was another ten seconds before the ground control team recognised that there was a serious problem. A back-up abort procedure was put into action by two ground controllers

|

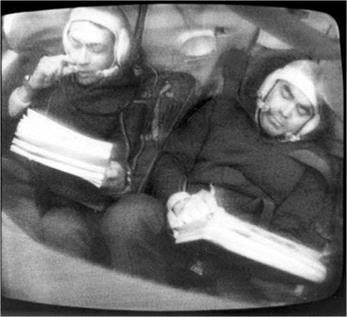

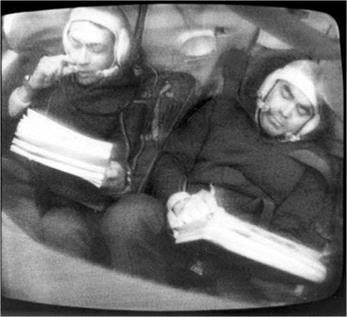

The Soyuz T10 abort cosmonauts Titov and Strekalov hoping to continue the programme they started on their T8 mission, five months before the pad abort

|

in separate rooms. Titov and Strekalov must have known that there was a problem because the booster was by now pitching over 35° and engulfed in flames. It could not be seen by the controllers. With barely a second remaining before the cosmonauts disappeared into the conflagration, the launch escape system at last sprang into life.

The Descent and Orbital Modules of Soyuz T10 were electronically severed from the instrument section inside the payload shroud and the twelve solid propellant rockets at the top of the escape tower ignited, producing a thrust of 80,000 kg (176,400 lb). Titov and Strekalov were airborne, as the booster exploded. Pulling 18 G, the cosmonauts were powerless at first, then five seconds later, four aerodynamic panels were folded out to stabilise the strange projectile. Twenty-five smaller propellant rockets fired to maintain stabilisation.

Instantly, the Descent Module containing Titov and Strekalov was severed and literally fell out of the payload shroud at an altitude of about 1,050 m (3,444 ft). The back-up parachute was deployed, because its swifter opening time was well-suited for the low-altitude opening, and the re-entry heatshield deployed to expose the soft – landing rockets. Soyuz T10 hit the ground about 3.2 km (2 miles) away, as the pad was a sea of flames, burning for over 20 hours. Titov and Strekalov were administered a stiff glass of vodka but did not need hospital treatment. The experience did not put them off space flight as each flew again, probably believing the old adage that lightning never strikes twice. That lightning had struck once took time to filter through to the west, for details were not released for some time.

Milestones

1st use of crew launch escape system

|

VOSTOK 1

|

|

|

Int. Designation

|

1961 mu 1

|

|

Launched

|

12 April 1961

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 1 (later known as the Gagarinskiy Start or Gagarin Pad), Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan

|

|

Landed

|

12 April 1961

|

|

Landing Site

|

30 km southwest of Engels, near Smelovako, Saratov

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

R7 (8K72K serial #E103-16); spacecraft serial number (11F63/3KA) #3

|

|

Duration

|

108 min

|

|

Callsign

|

Kedr (Cedar)

|

|

Objective

|

First manned test of Vostok spacecraft and launch vehicle systems, procedures and profiles

|

Flight Crew

GAGARIN, Yuri Alekseyevich, 27, Soviet Air Force, pilot

Flight Log

12 April 1961 dawned a fine spring day at the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Yuri Gagarin and his back-up, Gherman Titov, awoke in their tiny log cabin alongside a second cottage where the home of their mentor, the space designer Sergei Korolyov had found it hard to sleep. The two were suited up in the MIK building nearby, and by 08: 50 Baikonur time were at Pad 1, exiting from a bus in which they had travelled with many fellow cosmonauts. Traditional hugs and kisses followed at the foot of the rocket, before Gagarin left Titov grounded. Gagarin was inside his capsule (known as the “sharik” – sphere) by 09: 10 hours.

Instruments indicated that the hatch had failed to seal properly, delaying the launch by seven minutes. At 11: 07 hours, the engines of the Vostok booster sprang to life, building up to full thrust, while from the nearby blockhouse, Korolyov bid Gagarin farewell. The booster clamps were released and the cosmonaut was airborne. “Poyekhali” (“Off we go”) Gagarin exclaimed as the rocket lifted off. The rocket’s ascent was excellently filmed from the launch pad and its shimmering shadow moving across the flat steppe land of Kazakhstan is one memorable shot from the now frequently shown film, which was strictly off-limits in the West until 1967.

By 11: 21 hours (09: 21 hours Moscow time, 06: 21 hours gmt) Gagarin was in orbit, a mere passenger on an automatic flight, in which even the retro-fire would be triggered from the ground. Manual control was possible but not planned for the flight. Indeed, the manual controls were locked on Vostok (East) 1 (the Russians do not officially number the first spacecraft of a new type, although Soyuz TMA1 in 2002 was designated as such) but could have been released in an emergency, provided Gagarin was radioed a three-digit code to give him control. Gagarin sent messages of goodwill

|

Yuri Gagarin, shortly after his pioneering flight into space on 12 April 1961 in Vostok, the first entry in the manned space flight log book

|

and the unsurprising news that the Earth was “blue and the sky very, very dark.” Vostok, in its 65.07° inclination orbit (the highest inclination of a manned spacecraft to date), with a maximum altitude of 302 km (188 miles), sailed over the Pacific Ocean, South America and the Atlantic.

Over Africa, the retro-engine fired, initiating the re-entry, with the time on the clock at T + 1 hour 18 minutes into the flight, Moscow Radio having announced the launch just minutes earlier. The flight module initially did not separate cleanly, which could have resulted in the loss of Gagarin at the moment of his triumph. Fortunately the descent module did finally separate and made a 10-minute re-entry, ending at an altitude of 7 km (4 miles) with drogue parachute deployment. Gagarin ejected and reportedly landed close to bemused farm workers and a cow, 26 km (16 miles) southwest of Engels, near Smelovako, Saratov, at T + 1 hour 48 minutes, for the last 20 minutes of which Gagarin had not been aboard Vostok 1. The flight times of the Vostok cosmonauts and their capsules were released by Energiya in 2000. This revealed that the shariks landed about 10 minutes after the cosmonauts had parachuted to the ground. The time for Gagarin’s capsule was not revealed but this would imply that Gagarin’s “flight” landed at 1 hour 38 minutes – 98 minutes after launch. The fact that Gagarin had landed separately was not realised at the time in the West and not confirmed officially until 1978. Gagarin thus became the first of only six people so far – the Vostok pilots – to end a space flight without their spacecraft. Vostok 1 is also the shortest Soviet one-crew flight and the shortest manned orbital flight.

Milestones

1st manned space flight 1st Vostok manned flight

The next two flights after Gagarin were the two American sub-orbital flights by Alan Shepard on 5 May 1961, and Gus Grissom on 21 July 1961. Details of these flights can be found in the Quest for Space chapter.

|

Int. Designation

|

1970-041A

|

|

Launched

|

1 June 1970

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan

|

|

Landed

|

19 June 1970

|

|

Landing Site

|

75 km west of Karaganda

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

R7 (11A511); spacecraft serial number (7K-0K) #17

|

|

Duration

|

17 days 16 hrs 58 min 55 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Sokol (Falcon)

|

|

Objective

|

Extended-duration Earth orbital mission (18 days)

|

Flight Crew

NIKOLAYEV, Andrian Grigoryevich, 40, Soviet Air Force, commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Vostok 3 (1962)

SEVASTYANOV, Vitaly Ivanovich, 34, civilian, flight engineer

Flight Log

The Soviet Union’s first long-duration biomedical space mission, Soyuz 9, blasted away from Baikonur’s Pad 1 at 00: 00 hrs local time, the first manned launch at night, and was placed into a 51.6° orbit. During one of the five in-orbit changes, it reached a maximum altitude of 259 km (161 miles). In addition to medical experiments, including a torso harness which placed a load of about 40 kg (85 lb) on the cosmonaut’s body, and other exercising equipment, the crew of Andrian Nikolayev and Vitaly Sevastyanov made several meteorological and geological observations in the relatively spacious Orbital Module. These were thwarted to a degree by a spacecraft window that had been smeared by the plume from an engine firing. These observations were compared with simultaneous observations by satellites, ships and aircraft. The crew also tested a new orientation system based on star-lock navigation, using the bright stars Canopus and Vega. After setting a new world space endurance record, Soyuz 9 came home to a “sniper accurate’’ landing in a ploughed field, 75 km (47 miles) west of Karaganda at T + 17 days 16 hours 58 minutes 50 seconds.

Doctors were keen to see whether the exercise regime and spaciousness of the Soyuz had allowed the cosmonauts to overcome what was thought to be difficult readaptation to gravity. However, as both cosmonauts were so busy they began avoiding the exercise programme and, despite a rebuke from mission control, never managed to return to the planned schedule. Both cosmonauts complained of feeling extraordinarily heavy and had to be carried out of the Soyuz 9 descent capsule. They were kept under close medical supervision for ten days, complaining of feeling twice their real weight, walking with difficulty, becoming flushed and breathing heavily.

|

Sevastyanov (left) and Nikolayev shown in the Soyuz 9 DM during their record-breaking 18-day space marathon

|

They even stumbled up stairs. Nikolayev was moved to express extreme pessimism about the possibilities of long-duration space flights. He need not have worried, because the reason for their discomfort was that Soyuz 9 had been in a partial, intermittent, gravity-inducing controlled spin throughout the mission, and it was this that had caused most of their problems. Their lack of regular daily exercise was also a factor in their physical condition upon return. However, this challenging and difficult mission was a wholly successful one, and an important stepping stone towards starting the space station programme the following year.

Milestones

39th manned space flight

16th Soviet manned space flight

8th Soyuz manned space flight

1st night launch of a manned space flight

|

|

|

Int. Designation

|

1984-093A

|

|

Launched

|

30 August 1984

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

5 September 1984

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-103 Discovery/ET-12/SRB BI-013/SSME #1 2109; #2 2018; #3 2021

|

|

Duration

|

6 days 0 hrs 56 min 4 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Discovery

|

|

Objective

|

Maiden flight of OV-103 (Discovery); satellite deployment mission

|

Flight Crew

HARTSFIELD, Henry Warren “Hank”, 50, USAF, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-4 (1982)

COATS, Michael Lloyd, 38, USN, pilot MULLANE, Richard Michael, 38, USAF, mission specialist 1 HAWLEY, Steven Alan, 32, civilian, mission specialist 2 RESNIK, Judith Arlene, 35, civilian, mission specialist 3 WALKER, Charles David, 36, civilian, payload specialist

Flight Log

Scheduled for 25 June 1984, the first flight of the new orbiter Discovery was to clock up another first in space, with the transportation of the first fare-paying payload specialist. McDonnell Douglas paid NASA about $30,000 to fly Charles Walker to operate the Continuous Flow Electrophoresis System experiment, which he had helped to develop. CFES had flown before but McDonnell Douglas and NASA, both seeing the commercial possibilities, felt that CFES was on the verge of producing biological materials which could form the basis of a huge pharmaceutical space processing industry.

Walker also became the first payload specialist to make a late entry into a flight crew, which otherwise consisted of NASA career astronauts from the Group 8 cadre, which Walker himself had failed to join, and who had waited much longer to be assigned to a mission. The first launch attempt, already delayed three days, was stopped at T — 6 min by a fault in the fifth general purpose computer, and one day later, 2.6 seconds into main engine start for Discovery on Pad 39A on 26 June, engines three and two had ignited when both shut down with an alarming metallic graunching sound after the SSME 3 main fuel valve actuator channel A failed. This was the first launch pad abort in the Shuttle programme and the first in the US since

|

The first launch pad abort of the Shuttle programme was on 26 June 1984, for mission STS 41-D

|

Gemini 6 in December 1965. The abort was followed by a scare when residual hydrogen gas caught fire outside the Shuttle, but in the end the crew made a graceful exit after closing out the flight deck instrumentation.

As a result of the cancellation, missions 41-D and 41-F were merged and 41-D took on more cargo. All was ready again on 29 August but launch was cancelled due to computer software problems before the flight crew got aboard. The next day, it was delayed by a further 6 minutes 50 seconds by intruding aircraft. Finally, at 07: 07 hrs local time, Discovery was airborne heading for its 28.45°orbit and a maximum altitude of 286 km (178 miles). Three large communications satellites were successfully dispatched by the gleeful crew – a Shuttle first – and a 31 m (102 ft) solar sail was unfurled from the cargo bay. The longest structure erected in space, the Shuttle Power Extension Package prototype provided 250 watts of additional electrical power.

Walker, spending most of his time in the lower mid-deck, beavered away with CFES – which he had to repair – but its hormone biological material which was to be tested for its treatment for diabetes proved to be contaminated after the flight. Venting water from the fuel cell system had caused a large chunk of ice on the outside of Discovery, which the crew removed using the RMS thus making Hawley and Mullane’s unique contingency EVA unnecessary. The highly successful mission ended at T + 6 days 0 hours 56 minutes 4 seconds on Edwards runway 17, the shortest six – crew space flight.

Milestones

100th manned space flight 43rd US manned space flight 12th Shuttle flight 1st flight of Discovery 1st Shuttle pad abort

1st flight with a commercial payload specialist

|

Int. Designation

|

1989-021A

|

|

Launched

|

13 March 1989

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

18 March 1989

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 22, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-103 Discovery/ET-36/SRB BI-031/SSME #1 2031;

|

|

#2 2022; #3 2028

|

|

Duration

|

4 days 23 hrs 38 min 50 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Discovery

|

|

Objective

|

TDRS-D deployment mission

|

Flight Crew

COATS, Michael Lloyd, 43, USN, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-D (1984)

BLAHA, John Elmer, 46, USAF, pilot SPRINGER, Robert Clyde, 46, USMC, mission specialist 1 BUCHLI, James Frederick, 43, USMC, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS 51-C (1985); STS 61-A (1985)

BAGIAN, James Philip, 37, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

With the Shuttle up and rolling again, it did not take NASA long to establish an ambitious launch schedule for 1989, which would see seven launches starting with STS-29 on 14 February. The mission was soon put back to 23 February and was delayed again to at least mid-March. As a precautionary measure, the high-pressure oxidiser turbopumps on all three SSMEs on Discovery – by now already on Pad 39B – were replaced because stress corrosion cracks had been discovered on an SSME used for STS-27.

There was concern that the delay might cancel the mission altogether because STS-30 Atlantis needed to be on the pad by 23 March to meet the first day of its planetary launch window for the Magellan spacecraft. The work was completed satisfactorily and a date of 11 March set. Then a master events computer failure caused another delay to 13 March. It did not look too hopeful on this day either, as Discovery and the launch pad were draped in ground fog and there were concerns about conditions on the Kennedy runway should there be a return to launch site abort.

The count proceeded and was held at T — 9 minutes for 1 hour 50 minutes before Discovery rose majestically into the bright sunlit skies at 09: 57hrs local time – accompanied by the first female launch commentary of a US manned launch by NASA’s Lisa Malone – into its 28.45° inclination orbit which would reach a maximum

|

This view of the flight deck of Atlantis shows MS2 Buchli (left) and commander Coats (centre) at work. Pilot Blaha is hidden from view by his seat (right)

|

altitude of 283 km (176 miles). For the first time, photographs were captured of the external tank, looking like a fat cigar before being stubbed out during re-entry. In space at last were the original crew of STS 61-H, which was to have flown in June 1986 carrying Britain’s would-be first man in space, Sq. Ldr. Nigel Wood, had it not been for the Challenger disaster. The only newcomer to the crew was James Bagian who replaced Anna Fisher from the original 61-H mission.

At T + 6 hours 13 minutes, the primary payload of the mission, TDRS-D, was deployed, while concerns were raised about pressure surges in the fuel cells of the orbiter. The rest of the mission went swimmingly, concentrating on an array of science experiments and photography using the large format IMAX camera. The weather was so smooth at Edwards Air Force Base that a proposed crosswind landing test could not be performed, so commander Mike Coats aimed for runway 22 and a braking test on the concrete. Mission time was T + 4 days 23 hours 38 minutes 52 seconds. Discovery was in great shape and STS-29 proved to be one of the smoothest missions ever.

Milestones

124th manned space flight 58th US manned space flight 28th Shuttle mission 8th flight of Discovery 4th TDRS deployment mission

| | | |

1997-039A 7 August 1997

1997-039A 7 August 1997