MERCURY ATLAS 9

1963-015A

1963-015A

15 May 1963

Pad 14, Cape Canaveral, Florida

16 May 1963

128 km southeast of Midway Island, Pacific Ocean Atlas 130D; spacecraft serial number SC-20 1 day 10 hrs 19 min 49 sec Faith 7

First US 24-hour space flight

Flight Crew

COOPER, Leroy Gordon Jr., 36, USAF, pilot

Flight Log

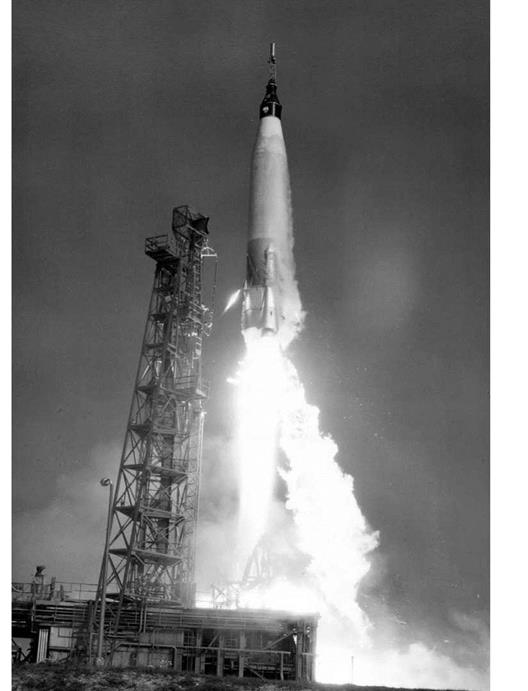

Such was the increased confidence in the Mercury spacecraft and manned space flight, that NASA not only planned a flight three times as long as Schirra’s, but also increased the duration again in November 1962 to a full 22 orbits. The man in the hot seat, Gordon Cooper, was named the same month, with a May 1963 launch date as the target. Cooper, who affirmed his faith in God, his country and the Mercury team by naming his spacecraft Faith 7, had a packed flight plan, with emphasis on photography. He called the mission, the “flying camera’’. The camera was fixed on to the tripod on 22 April and was ready to go on 14 May.

Unfortunately, the gantry tower refused to budge because water had seeped into its diesel fuel pump and when the gantry was moved away two hours later, radar data from the Bermuda tracking station was insufficient and the launch was scrubbed. Not so on 15 May, when the relaxed Cooper awoke from a catnap in Faith 7 in time to be launched at 08: 04 hrs local time. He reached his 32.5° orbit with an apogee of 267 km (166 miles) and a peak velocity of 28,238 kph (17,547 mph) five minutes later. Cooper remained extremely unruffled and calm throughout the flight, which featured the first in-flight television from a US spacecraft, although the pictures were disappointing.

Cooper’s photography from Faith 7, however, was a revelation, confirming to observers his own reports of being able to see the wakes of ships and smoke from a log cabin in the Himalayas with the naked eye. Cooper deployed a small flashing beacon from Faith 7, the first deployment in history, as well as a tethered balloon like Schirra’s. The flight went swimmingly, with Cooper becoming the first American to sleep in space, but during the nineteenth orbit, the astronaut noticed the one-G light coming on, which apparently detected the onset of gravity.

Tracing the cause, the astronaut discovered that the attitude and stabilisation control system a/c converter had failed. The astronaut would have to perform an

|

Gordon Cooper heads for orbit aboard Mercury Atlas 9 |

entirely manual re-entry, which he did perfectly, splashing down just 7 km (4 miles) from the USS Kearsage, 128 km (80 miles) southeast of Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean, at T + 1 day 10 hours 19 minutes 49 seconds, the longest launch-to-landing solo US manned space flight in history. A planned three-day mission (Mercury-Atlas 10/Freedom II, flown by Alan Shepard) was mooted but scrapped, and the Mercury programme ended officially on 12 June 1963

Milestones

10th manned space flight

6th US manned space flight

6th and final Mercury manned flight

1st satellite deployment from manned spacecraft

|

VOSTOK 5 |

AND 6 |

|

Int. Designation |

1963-020A (Vostok 5); 1963-023A (Vostok 6) |

|

Launched |

14 (Vostok 5) and 16 (Vostok 6) June 1963 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan (both launches) |

|

Landed |

19 June 1963 |

|

Landing Site |

619.4km northeast of Karaganda, Kazakhstan (Vostok 6); 539 km northwest of Karaganda, Kazakhstan (Vostok 5) |

|

Launch Vehicle |

R7 (8K72K); spacecraft serial number (11F63/3KA) #7 (Vostok 5); and #8 (Vostok 6) |

|

Duration |

4 days 23 hrs 6 min (Vostok 5); 2 days 22 hrs 50 min (Vostok 6) |

|

Callsign |

Yastreb (Hawk) – Vostok 5; Chaika (Seagull) – Vostok 6 |

|

Objective |

Second group flight; five-day solo flight and first female space flight |

Flight Crew

BYKOVSKY, Valeri Fyodorovich, 28, Soviet Air Force, pilot Vostok 5 TERESHKOVA, Valentina Vladimirovna, 26, Soviet Air Force, pilot Vostok 6

Flight Log

The much-rumoured launch of Vostok 5 was delayed by bad weather on 13 June but the following day, at 17:00 hrs local time at Baikonur, launch pad 1 reverberated to the sound of another SL-3 ignition as cosmonaut Valeri Bykovsky began what was planned as a long-duration mission. At 4 days 23 hours 6 minutes, it actually became (and still remains) the longest manned solo space flight in history. Vostok 5 entered a 65° inclination orbit with an apogee of 209 km (130 miles) as rumours persisted that another Vostok would be launched the following day. It was to be a Vostok that would overshadow Bykovsky’s feat.

Vostok 6 carried the first woman (and tenth human) to venture into space. Valentina Tereshkova was launched at 14: 30 hrs Baikonur time. Reflecting the frenetic space activity of the 1960s, in between the Vostok 5 and 6 launches, the USA had performed six satellite launches, all from California. Vostok 6 entered a 65° inclination orbit with a peak altitude of 218 km (135 miles) and almost immediately came to within 5 km (3 miles) of Vostok 5 for a brief encounter, which according to the western press went much further, with such headlines as “Valya chases her space date’’.

As Tereshkova was not a pilot, it was perhaps inevitable that she reportedly had difficulties in adapting to weightlessness, but the rumours of her being so ill that she pleaded to come home seem far-fetched, as it appears that the flight, originally

|

Tereshkova and Korolyov in discussion prior to her historic space flight |

planned to be a 24-hour affair, was in fact extended. The launch of a woman into space was undoubtedly a major propaganda coup for Premier Khrushchev, who may have ordered such a mission, a theory supported by the fact that the next woman to fly into space was not launched until 1982.

Tereshkova was the first of the space pair to land, 624 km (388 miles) northeast of Karaganda at mission elapsed time of 2 days 22 hours 50 minutes. As the landing was a nominal one, she is thus the only woman to end a space flight outside her spacecraft, as well as the only one to make a solo female space flight. Bykovsky was the third Vostok pilot to experience a partial separation of the descent module but the separation occurred prior to the worst part of the re-entry profile and he returned to Earth about 540 km (336 miles) northwest of Karaganda. Plans were set in motion for a Vostok 7 mission lasting a week, by “non-cosmonaut” doctor Boris Yegorov, in the summer of 1964 but, like the US Mercury programme, the Soviet Vostok project ended after six flights. However, the next series of spacecraft (Soyuz, or “Union”) would not be ready for some time and so in order to appear ahead in the space race with the Americans, the Vostok was converted into what seemed to outsiders to be a radically new and improved spacecraft – Voskhod.

Milestones

11th and 12th manned space flights 5th and 6th Soviet manned space flights

5th and 6th Vostok manned flights

1st space flight with female crew (Vostok 6)

1st joint male-female space flight

Bykovsky has held the solo space flight record for over 43 years

On 27 June 1963, Robert Rushworth, 39, of the USAF flew X-15-3 on the third astro – flight, to 88 km. Less than a month later, on 19 July 1963, Joe Walker, 42, flew the same vehicle on the fourth astro-flight, this time to 105 km. Finally this year, on 22 August 1963, Walker flew X-15-3 to 107 km in the fifth astro-flight, the highest altitude any X-15 would attain.

|

Flight Crew

KOMAROV, Vladimir Mikhailovich, 37, Soviet Air Force, commander FEOKTISTOV, Konstantin Petrovich, 38, civilian, flight engineer YEGOROV, Boris Borisovich, 27, civilian, doctor

Flight Log

Voskhod (“Sunrise”) 1 provided the classic illustration of how the secret Soviet space programme completely misled the west. After the Vostok missions, Sergei Korolyov, the then anonymous space designer, considered improvements to the basic spacecraft to allow longer missions by more than one passenger. These studies led to the design of a new spacecraft, Soyuz, which would perform Earth orbital and lunar looping missions and support a possible lunar landing programme. Delays to Soyuz meant that there would be a hiatus in the manned space programme, to which Premier Khrushchev reacted in customary fashion, demanding a multi-crewed space flight before the United States launched its two-man Gemini spacecraft in early 1965.

As Soyuz could not be accelerated, Korolyov responded with a version of the uprated Vostok. But in order to launch three men rather than two, as the Americans were planning, practically all the “stuffing” had to be taken out of Vostok and the crew would have to fly without spacesuits and without any means of emergency escape. Voskhod would, however, carry a back up retro-rocket. Despite the imperfections of Voskhod, seven cosmonauts seemed happy to be assigned to train for the most risky manned space flight in history. The three to be chosen were a commander, Vladimir Komarov, a scientist, Konstantin Feoktistov – who, it turned out, was the man who helped design Vostok to fly with three passengers – and a doctor, Boris Yegorov.

They arrived at the launch pad wearing cotton overalls and leather flying helmets, about to board the first SL-4 booster to fly a manned crew a few days after the one and only “test flight” of the “new” Voskhod, as Cosmos 47. Launch came at 12: 30hrs Baikonur time and soon after the spacecraft had reached its 65°, 409 km (254 miles)

|

The first “space crew” walk down the red carpet to report on the success of their mission to welcoming officials in Moscow. L to r Feoktistov, Komarov, Yegorov |

maximum altitude orbit, the western media went wild, reporting that Russia had launched a “mammoth” new spaceship in which the scientist and doctor would perform experiments while the commander controlled the mission. In truth, the conditions were so cramped inside the Voskhod that it must have been hard to eat and go to the toilet, let alone perform experiments, although Yegorov apparently performed some basic medical checks.

Khrushchev had the propaganda success he wanted, but as he was congratulating the crew by telephone, the receiver was taken from his hands. The Brezhnev-Kosygin takeover had begun and it was they who greeted the fortunate cosmonauts after they had landed safely. The crew remained in the spherical capsule as small retro – rockets fired just before touchdown to cushion the impact, some 310 km (193 miles) northeast of Kustanai. The mission lasted just 1 day 17 minutes 3 seconds, the shortest three-crew flight in history. The three-man crew apparently requested an extension but were refused by Korolyov, who quoted Shakespeare: “There are more things in heaven and Earth, Horatio…” At the time, no one knew the name of the chief designer, who had one more spacecraft to design before he succumbed to ill health in January 1966.

Milestones

13th manned space flight

7th Soviet manned space flight

7th Vostok manned flight

1st Voskhod manned variant flight

1st three-person crew

1st flight by crew without spacesuits

1st flight with no launch escape or ejection system

1st Soviet space flight to end with crew inside spacecraft

1st space flight with non-pilot, civilian crew

1965-022A

18  March 1965

March 1965

Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan

19 March 1965

180 km northeast of Perm, Siberia

R7 (11A57); spacecraft serial number (11F63/3KD) #4

1 day 2hrs 2 min 17 sec

Almaz (Diamond)

First Extra-Vehicular Activity (EVA – spacewalk) demonstration

Flight Crew

BELYAYEV, Pavel Ivanovich, 39, Soviet Air Force, commander LEONOV, Alexei Arkhipovich, 30, Soviet Air Force, pilot

Flight Log

The second of a planned series of multi-crew Voskhod missions got underway at 12: 00 Baikonur time, entering a 65° inclination orbit with the highest manned apogee to date of 495 km (308 miles). Instead of three crewmen without spacesuits, there were two, this time suitably attired. This Voskhod had been reconfigured to carry a telescopic airlock leading from the crew cabin. The space where the third seat had been was left free to give one of the crewmen, Alexei Leonov, the room in which to don an emergency oxygen backpack and connect an umbilical air and communications tether to his spacesuit, before crawling through the airlock after the spacecraft had been depressurised.

The first walk into open space began at the start of the second orbit of Voskhod, as Leonov emerged from the airlock at the end of his 5 m (16 ft) tether, watched by two television and film cameras attached to the end of the airlock and on top of the backup retro-rocket. Leonov cavorted in space doing cartwheels, not for show but because he was essentially out of control as his umbilical snaked around. His official free spacewalk lasted 12 minutes 9 seconds, but he was in the vacuum environment for about 20 minutes, since he couldn’t get back into the airlock. His spacesuit had ballooned more than anticipated and he had to squeeze himself back into the airlock quite forcibly before closing the hatch and re-pressurising the spacecraft.

Unfortunately, he forgot to retrieve the film camera which would have shown clear photos of the EVA rather than the blurred and fuzzy television reproductions. Nonetheless, Leonov’s exploits had a dramatic effect on the watching world, capturing more headlines than Gagarin himself, and this mission was one of the highlights of the “Space Age’’ of the 1960s. The rest of the flight went quietly until they

|

The first “walk” in space |

attempted retro-fire at the end of the seventeenth orbit. The prime retro-rocket in the instrument module of Voskhod failed to fire because of a sensor attitude control malfunction.

The cosmonauts made one more orbit as, not without a certain amount of drama, preparations were made to fire the back-up retro-pack on the next pass. The instrument section was apparently jettisoned (again not cleanly) before this, and the Voskhod spherical flight cabin was manually orientated by Belyayev, who punched the retro-pack arming device. The re-entry was quite dramatic and the capsule naturally missed the main recovery area by 960 km (597 miles), landing in the thick, snow – covered forest near the city of Perm. A damaged telemetry antenna made it impossible for the rescue teams to locate the craft, so the cosmonauts put their emergency landing training into effect, lighting a fire and waiting for rescue. However, ravenous wolves compelled their return to the capsule and it was two and a half hours before a helicopter spotted the capsule, thanks to the parachutes which were splayed out across the tree tops. Ground vehicles rescued the crew after they had spent a night in the forest.

Observers in the west, expecting a landing announcement to be made at the end of the seventeenth orbit, suspected that something was wrong and were only told of the touchdown when the crew had been located, four hours later. The drama of

the landing events was only fully revealed a year later, rather perversely, after the emergency US landing of Gemini 8. Flight time was 1 day 2 hours 2 minutes 17 seconds. This proved to be the last Voskhod manned mission. There had originally been plans for a series of at least seven manned Voskhod flights. Voskhod 3 was to have been a two-man 15-20-day extended scientific mission, and then Voskhod 4 would have flown a 15-day biomedical mission with a cosmonaut doctor in the crew. Voskhod 5 would be an all female crew with an EVA, Voskhod 6 was a 14-day EVA mission featuring the use of a small manoeuvring unit, and Voskhod 7 would attempt tether dynamics with the spent upper stage before flying a 10-15 day mission. There was also a plan to include a professional Soviet journalist on board a Voskhod but all these flights were cancelled.

Milestones

14th manned space flight

8th Soviet manned space flight

8th Vostok manned flight

2nd Voskhod manned variant flight

1st manned space flight with two crew

1st space flight with EVA operations

1st extended mission

|

Flight Crew

GRISSOM, Virgil Ivan “Gus”, 39, USAF, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Mercury-Redstone 4 (1961)

YOUNG, John Watts, 35, USN, pilot

Flight Log

Project Gemini was born as the logical follow-on to the Mercury programme, but its raison d’itre was changed by President Kennedy’s pledge to land a man on the Moon before 1970. Gemini was to act as the testing ground for all the manoeuvres and operations to be performed on an Apollo mission, but in Earth orbit – orbital manoeuvring, rendezvous, docking, extended flights and spacewalking. The task of Gemini 3 was straightforward: with the aid of the first computer on a manned spacecraft, Gemini 3 would change its orbit.

The crew was chosen at the time of the Gemini 1 unmanned test flight and was well into training by the time unmanned Gemini 2 had become the first to be recovered. Command pilot Gus Grissom and his pilot John Young, the Taciturn Twins as they were dubbed, were overshadowed by the exploits of Voskhod 2 five days earlier, particularly as Gemini 3 was to make only a modest three orbits. The crew were lying in their ejector seats inside Gemini 3 at 07: 30 hrs, waiting for a 09: 00 hrs launch. At T — 35 minutes, the Titan II first-stage oxidiser line sprang a leak and a handy wrench was required, delaying the launch by 24 minutes. The hypergolic engines of the Titan gave out a high-pitched whine and sprang to life and the mission lifted off.

As the second stage ignited while still attached to the first stage, its exhaust spewing out of the lattice framework between the two, the rocket was surrounded by a bright aurora, disconcerting the pilot. After reaching the 32.5°, 224km (139 miles) peak apogee orbit, the crew was immediately assigned to a series of science

|

Young (left) and Grissom aboard Gemini 3 |

experiments, including a sea urchin cell growth experiment, which failed because Grissom was rather heavy-handed with it.

At last, the frustrated astronauts had some real space flying to do as, at T + 1 hour 30 minutes, Grissom performed the first orbital manoeuvring system burn, for 75 seconds. Two more burns followed, with the last placing Gemini 3’s perigee at 72 km (45 miles), low enough to ensure re-entry even if the retros failed to fire, which they didn’t. Grissom tried to use Gemini’s lift capability to reduce a predicted landing miss but the capability of the spacecraft was less than anticipated and resulted in a 111 km (69 miles) miss. As Gemini assumed splashdown position, it literally yanked from vertical to an almost horizontal position, pitching the crew forward and smashing Grissom’s faceplate against the instrument panel.

The flight ended near Grand Turk Island in the Atlantic Ocean at T + 4 hours 52 minutes 51 seconds, the shortest US two-crew mission. The landing miss meant a long wait in heaving seas but Grissom – remembering Liberty Bell – elected to stay on board with the hatch well and truly closed. Grissom lost his pre-launch breakfast and both doffed their spacesuits in the heat. They later walked rather ignominiously along the deck of the carrier Intrepid, to which they had been helicoptered, in sporting underwear beneath bathrobes. After the Liberty Bell 7 incident, Grissom named his next space craft “Molly Brown’’ after the hit Broadway show “The Unsinkable Molly

Brown”. NASA was not happy about this and asked him to change the name, but when he indicated that his second choice was “Titanic” they relented. “Molly Brown” became the last named American spacecraft until Apollo 9 in March 1969.

Gemini 3 became known as the “corned beef sandwich flight”, when afterwards it was revealed that Young had been reprimanded for carrying food aboard and offering it to Grissom who, on taking a hefty bite, spread crumbs around the cabin. The prank was, not surprisingly, hatched by the back-up command pilot, Wally Schirra, who put the sandwich into Young’s spacesuit, but the joke got out of hand and became the subject of a Congressional inquiry. The cost of the sandwich, which Schirra had bought in Cocoa Beach, escalated, and it became known as the “$30 million sandwich’’.

Milestones

15th manned space flight 7th US manned space flight 1st Gemini manned flight

1st manned space flight to perform orbital manoeuvres

1st US two-man crew mission

1st flight by crewman on second mission