1997-039A 7 August 1997 1997-039A 7 August 1997

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 19 August 1997

Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida

OV-103 Discovery/ET-87/SRB BI-089/SSME #1 2041;

#2 2039; #3 2042

11 days 20hrs 26 min 59 sec

Discovery

CRISTA-SPAS-02 operations

Flight Crew

BROWN Jr., Curtis Lee, 41, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-66 (1994); STS-77 (1996)

ROMINGER, Kent Vernon, 41, USN, pilot, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-73 (1995); STS-80 (1996)

DAVIS, Jan, 43, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-47 (1992); STS-60 (1994)

CURBEAM Jr., Robert Lee, 35, USN, mission specialist 2 ROBINSON, Stephen Kern, 41, civilian, mission specialist 3 TRYGGVASON, Bjarni Vladimir, 52, civilian, Canadian payload specialist 1

Flight Log

Continuing the Mission to Planet Earth programme, as well as preparations for the construction of ISS, the STS-85 mission featured a complex payload from Germany, Japan and the US, as well as an international crew.

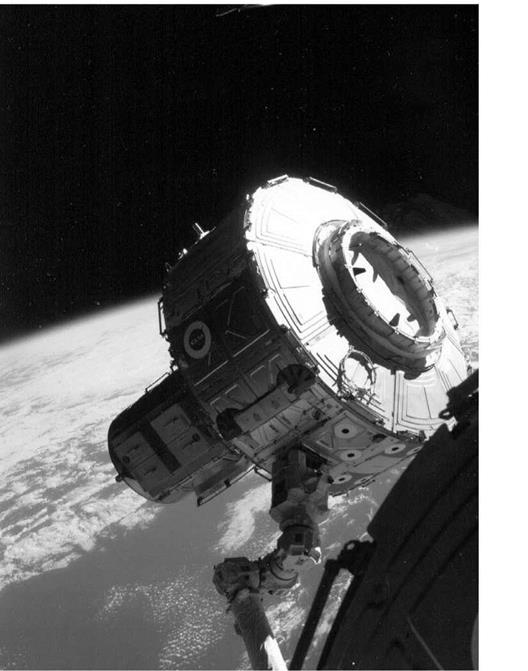

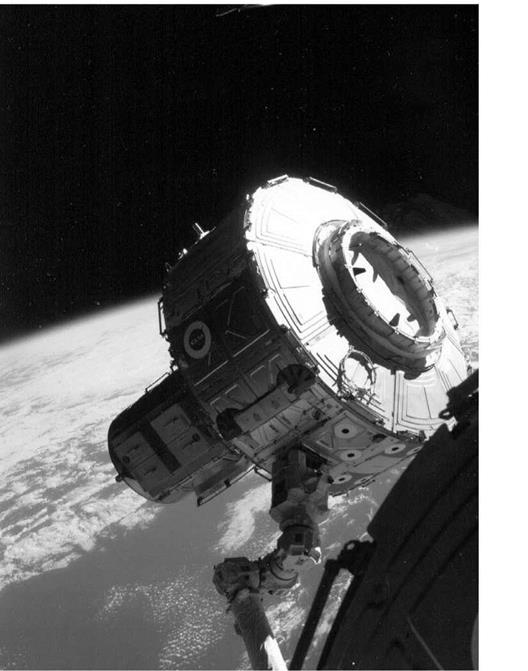

The primary payload on this flight was the Cryogenic IR Spectrometer and Telescope for the Atmosphere Shuttle Pallet Satellite-2 (CRISTA-SPAS-2), making its second flight on the Shuttle as part of the fourth cooperative mission between the German space agency DARA and NASA. There were three telescopes and four spectrometers on the satellite. Deployed on FD 1, it operated for over 200 hours and was retrieved on FD 10. After completing its primary objective, CRISTA-SPAS was used in a simulation exercise to prepare for the first ISS assembly flight, STS-88, with the payload being manipulated as if it were the Russian Functional Cargo Block (FGB-Zarya) that was to be attached to the US Node 1 (Unity).

The Technology Applications and Science 01 (TAS-01) payload included seven separate experiments to gather data on the topography of the Earth and its atmosphere, to study the energy from the Sun and to evaluate new thermal control devices. International Extreme UV Hitchhiker 02 was a set of four experiments that studied

|

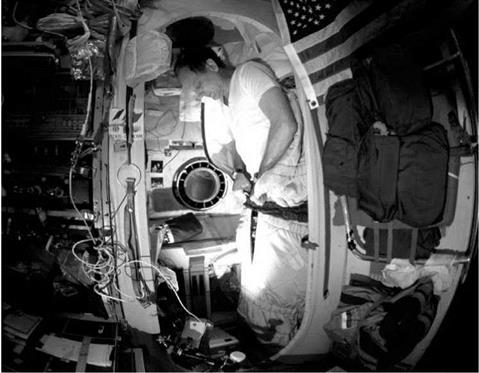

Canadian astronaut Bjarni Tryggvason inputs data into a computer for the Microgravity Vibration Isolation Mount (MIM) experiment located on the mid-deck of Discovery. Behind him, the use of mid-deck lockers for stowage both inside and outside is evident

|

UV radiation from stars, the Sun and other solar system sources. The Japanese Manipulator Flight Demonstrator (MFD) consisted of three separate experiments located on a support structure in the payload bay and were designed to test a mechanical arm that was being evaluated for possible inclusion on the Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) planned for ISS. Despite some glitches, a series of exercises was performed by the crew in space and a team of operators on the ground.

There was also a range of in-cabin payloads, including a UV imaging system to observe Comet Hale-Bopp, crystal growth and materials-processing experiments, the Orbiter Space Vision System (to be used during ISS assembly for determining precise alignment and pointing capability). Canadian astronaut Bjarni Tryggvason, principle investigator of the Microgravity Vibration Isolation Mount (MIM), had a major role on the flight in evaluating his own equipment, performing fluid physics experiments to determine sensitivity to spacecraft vibrations when using MIM, and its application to ISS and future research facilities. The MIM had been in operation aboard Mir since April 1996 and was first operated by Shannon Lucid, where it supported a number of Canadian and US experiments in materials science and fluid physics.

The 18 August landing opportunities were waived off due to ground fog in the local area, allowing the crew an extra day on orbit.

Milestones

201st manned space flight 116th US manned space flight 86th Shuttle mission 23rd flight of Discovery

Flight Crew

MUSABAYEV, Talgat Amangeldyevich, 50, Russian Air Force, commander, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM19 (1994); Soyuz TM27 (1998)

BATURIN, Yuri Mikhailovich, 51, Russian political aide, flight engineer,

2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM28 (1998)

TITO, Dennis, 60, civilian, US space flight participant

Flight Log

Soyuz TM32 was scheduled to be the mission that exchanged the Soyuz (TM31) that had carried the first resident crew to the station six months before. The mission was also known as Taxi-1. However, just to confuse things, the Russians decided to rename these missions (and the Progress flights) by order of flight sequence to the new station. So Soyuz TM31 became Soyuz 1 (the original of which actually flew in 1967) and the first Progress (M1-3) became Progress 1 (which originally flew in 1978). Soyuz visiting missions had been conducted for some time with their own space stations, with Russian cosmonaut crews exchanging the Soyuz craft every six months at the end of the vehicle’s “shelf-life”. Beginning with ISS-2, main crews for the new station would be launched and landed on the Shuttle, though all crews would be trained on Soyuz entry and landing procedures, at least for the foreseeable future as the station was being constructed. The crew would include one experienced commander, one rookie flight engineer and, since Soyuz carried a third seat, the opportunity to fly a second Russian or international cosmonaut to ISS. Russia also quickly realised that this was a seat worth selling. The idea of flying fare-paying passengers on short visiting missions became a possibility near the end of the Mir programme, but that station was de-orbited before a “space tourist’’, or space flight participant (SFP) had the chance to pay the US$20 million price tag for the privilege. With ISS, the opportunity for such flights was once again available.

|

The first “space tourist”, Dennis Tito (left), is safely back on Earth after his $20 million flight into space. Musabayev (centre) and Baturin are shown with him, having exchanged the TM31 craft for the fresher TM32

|

NASA was not happy about less than fully trained crew members flying to the ISS. As the station was under construction, there was the concern about the tourist endangering the resident crew or affecting the smooth operation of the mission. However, as the Russians were flying the passenger, NASA had no veto over the decision. Instead, they did try to curtail such tourists’ station access to the Russian elements only. The first to fly in this way was American businessman and millionaire Dennis Tito, who had been planning a trip to Mir and was offered a ride to ISS to compensate.

After much media coverage, the TM32 crew arrived at ISS at the nadir port of Zarya. Though TV views of the crew transfer to the station were received, NASA indicated that only Russian-supplied images would be available, not theirs. The short programme of the Kristall crew included Earth observations, a seed and biology experiment, a food digestive experiment, crystal experiments and “commemorative activities”. On board the station, the Taxi crew were called cosmonaut researchers 1 (Musabayev), 2 (Baturin) and 3 (Tito). Tito also used video and still cameras to record activities on board the station. In a Russian press conference, Tito mentioned that he had indeed visited the US segment several times. Despite reports that he suffered from space sickness, Tito indicated that he “liked space.’’ Both Musabayev and Usachev reported that Tito had not hindered the work of the main crew and had assisted in meal preparations. Voss and Helms were advised by NASA to keep their activities with Tito to formal participation. In light of the visit of Tito, NASA amended its procedures for approving visiting “tourists” to ISS. Future visitors would now have to participate in basic safety and awareness training at JSC, and those “tourists” who followed Tito would have to develop a stronger scientific programme to occupy them during their week on the ISS.

The crew came home in the TM31 spacecraft on 6 May. A faulty infrared vertical sensor reportedly caused them to overshoot their landing site by 56 km. The landing was a hard one, so hard that Musabayev had to check whether his $20 million passenger was still alive! The mission certainly generated further interest in “Soyuz seats for sale” and provided the possibility of short visiting missions to ISS to exchange the Soyuz and, while there, conduct small science programmes that would not interrupt the main work of the resident crew. This was the continuation of the Interkosmos programme that the Russians had developed over 20 years before.

Milestones

225th manned space flight 91st Russian manned space flight 84th manned Soyuz mission 31st manned Soyuz TM mission 2nd Soyuz ISS ferry mission 1st Soyuz visiting mission 1st space flight participant (Tito)

Flight Crew

LINDSEY, Steven Wayne, 40, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-87 (1997); STS-95 (1998)

HOBAUGH, Charles Owen, 39, USMC, pilot

GERNHARDT, Michael Landen, 44, civilian, mission specialist 1, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-69 (1995); STS-83 (1997); STS-94 (1997)

REILLY II, James Francis, 47, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-89 (1998)

KAVANDI, Janet Lynn, 42, civilian, mission specialist 3, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-91 (1998); STS-99 (2000)

Flight Log

This mission completed the second phase of ISS assembly by providing an airlock facility that would allow EVAs to be conducted from the station without the need for a Shuttle to be docked to it. Atlantis docked with ISS on 13 July and would remain there for the next 196 hours. The mission’s three EVAs supported the installation of the Joint Airlock module (called Quest) on the station.

The first EVA (14 Jul for 5 hours 59 minutes) saw Gernhardt (EV1) and Reilly (EV2) remove insulation covers from berthing mechanisms on the airlock and install bars to what would be the attachment points for the four high pressure gas tanks. Using Canadarm2, ISS-2 crew member Susan Helms then lifted the airlock out of the payload bay of Atlantis and installed it on the right side of Unity. The EVA crew then attached heating cables from the station to the airlock and positioned foot restraints to support future EVAs. Three days later (17 Jul for 6 hours 29 minutes), the EVA crew returned to Quest to install the three tank assemblies on the airlock with the help of both the station and Shuttle robotic arm systems. The final EVA four days later (21 Jul for 4 hours 2 minutes) was the first out of the Quest airlock. During the

|

|

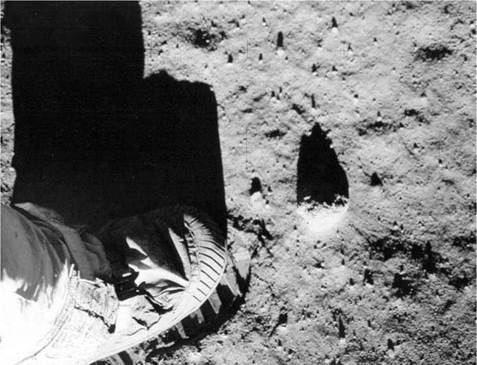

The Quest airlock is in the process of being installed onto the starboard side of Unity Node 1 of ISS. The airlock, delivered by STS-104, is being moved by ISS-2 FE Susan Helms using the SSRMS Canadarm2 from a control panel located in the US Destiny laboratory excursion, the EVA crew installed further tank assemblies on the outside of the station, again with the help of both RMS systems. In the days between each EVA, nitrogen and oxygen lines were tested and valves installed inside the facility to connect Quest to the ISS ECLSS. A computer was also installed to manage the airlock systems. Air bubbles in a coolant line caused a water spill and its clean-up postponed other activities for a day. A leaky air circulation valve was replaced and the hatch was relocated from its initial location between the airlock and the Unity Node hatch to become an inner EVA hatch between the equipment lock (storage and servicing of EVA equipment) and the crew lock (access to open space). A dry run using the Quest systems was performed prior to formal inauguration on 21 July, just hours after the 32nd anniversary of the first lunar EVA on Apollo 11 on 20 July 1969.

Undocking from ISS occurred in the early hours of 22 July, and after a 24-hour waive-off due to weather conditions in Florida, Atlantis achieved a night time landing back at the Cape the following day. Between July 2000 and the arrival of Quest, over 69,853 kg of hardware had been added to the station. This included the Zvezda module, the Z1 Truss (STS-92), PMA-3 (STS-92), the P6 assembly and solar arrays (STS-97), the US Destiny lab (STS-98), Canadarm2 (STS-100) and now Quest (STS – 104). This would allow the station to conduct independent operations. Though future assembly missions and re-supply missions would still be required, the crews on board the station could now conduct expanded programmes of science and station-based EVAs, as well as routine maintenance and housekeeping duties.

Milestones

226th manned space flight 135th US manned space flight 105th Shuttle mission 24th flight of Atlantis

49th US and 82nd flight with EVA operations 10th Shuttle ISS mission 4th Atlantis ISS mission 1st EVA from Quest airlock

Flight Crew

KRIKALEV, Sergei Konstaninovich, 46, civilian, Russian ISS-11 and Soyuz commander, 6th mission

Previous missions: Soyuz TM7 (1988); Soyuz TM12 (1991); STS-60 (1994); STS-88 (1998); ISS-1 (2000/01)

PHILLIPS, John Lynch, 54, civilian, US ISS-11 science officer, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-100 (2001)

VITTORI, Roberto, 40, Italian Air Force, Soyuz flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM34 (2002)

Flight Log

The eleventh residency aboard ISS would be the first to receive a Shuttle mission since STS-113 in December 2002. The loss of Columbia and her crew had created the need to fly two-man resident crews, termed caretakers, because orbital operations were restricted by the availability of onboard supplies, and station expansion curtailed by the grounding of the Shuttle. This was the fifth such caretaker crew, but the docking of STS-114 in July signified that full station operations could soon be resumed.

Flying to the station with EO-11 was ESA astronaut Vittori, who completed 23 experiments in 91 sessions under the Eneide programme. His research consisted of studies in human physiology, biology, demonstrations of new technology and a programme of education demonstrations. Vittori would also participate in a number of ceremonial and public relations broadcasts, a feature of most crew exchanges and international missions in space. Vittori would return to Earth aboard TMA5 along with the two ISS-10 crew members.

Almost as soon as the new crew were left alone on the station, their time was taken up by problems with the Elektron system, which finally broke down in early May.

|

Change of shift on ISS. The ISS-10 and 11 crews give the thumbs-up to the continuation of manned station operations. L to r John Phillips and Sergey Krikalev (ISS-11), Leroy Chiao (ISS-10), Italian Roberto Vittori (ESA) and Salizhan Sharipov (ISS-10)

|

There were sufficient alternative oxygen supplies aboard the station to keep the crew supplied until the end of the year, with re-supply by the Shuttle and Progress, but it was still disconcerting as troubleshooting on the unit would be added to an already heavy work programme. Other maintenance included work on the treadmill vibration isolation system. The crew received their first re-supply craft (Progress M53) in June, which delivered 2,383 kg of cargo. This included 111 kg of oxygen and 420 kg of water, as well as 40 solid fuel oxygen generation cartridges and spare parts for the Elektron unit.

The crew also completed a range of science studies, including Earth observations, medical experiments, and microgravity research. In addition they tested new software that had been installed to support the Canadarm2 unit on the station and relocated their Soyuz from the Pirs module to the Zarya module on 19 July, freeing the docking compartment for their EVA the following month. The re-docking operation took approximately 30 minutes to complete. During these relocation manoeuvres, the station had to be prepared for autonomous flight, in case the Soyuz failed to re-dock and the crew were forced to return to Earth.

On 28 July, the STS-114 crew docked Discovery with the station, bringing much – welcomed supplies and visitors to the crew, and confidence in the resumption of Shuttle ISS assembly flights. In August, the Russian Vodzukh carbon dioxide removal system failed and while the Russian ground controllers investigated the problem and came up with a repair plan, the American unit in Destiny was activated to take over the operation. On 16 August Krikalev surpassed Sergei Avdeyev’s career record of time logged in space (747 days 14 hours 14 minutes 11 seconds).

The two men performed their only EVA on 17 August (4 hours 57 minutes). For Phillips, it was the first excursion outside a spacecraft in space, but for veteran Krikalev, this was his eighth EVA. Their tasks included retrieving exterior sample cassettes, installing a new reserve TV camera for ATV dockings, and photographing exterior experiments and surfaces. Some of the activities planned for the EVA could not be accomplished due to lack of time and would be rescheduled for later crews. Following their EVA, the crew cleaned their equipment and resumed their scientific and maintenance work in preparation for their next visitors, the crew of Soyuz TMA7 and the third space flight participant. In their final days in orbit, the two men began packing up their research results, increased their exercise programme in preparation for the return to gravity and checked the systems of Soyuz TMA6. They would return to Earth with space flight participant Greg Olsen after he completed his week aboard the station.

During the descent of TMA6, there was a small pressure leak from the DM, which was noted before the undocking from ISS. An obstruction of some kind seemed to have prevented the air tight seal of the forward DM hatch into the OM. On module separation the leak continued to vent, although the crew were protected in their Sokol suits. The landing occurred successfully but Phillips had to be given smelling salts to prevent him drifting into unconsciousness. The astronaut later explained that he was far more uncomfortable in the DM than he had been in the Shuttle he had returned on in 2001. He was not sure if he became unconscious for a short time, but he knew his head was spinning. In images from the recovery operation, he certainly looked weak and pale.

Milestones

243rd manned space flight

99th Russian manned space flight

92nd manned Soyuz mission

6th manned Soyuz TMA mission

39th Russian and 93rd flight with EVA operations

10th ISS Soyuz mission (9S)

8th visiting mission (VC-7)

5th resident caretaker ISS crew (2 person)

Phillips is launched on his 54th birthday (15 Apr)

Krikalev celebrates his 47th birthday in space (27 Aug)

Krikalev sets a new cumulative record of 803 days 9hrs 39 mins in space, on six missions

1st cosmonaut to fly six missions (Krikalev)

1st person to conduct a second residence aboard ISS (Krikalev)

One of the most frustrating and time consuming chores to do with collating data on each manned space flight is in finding original source material that is consistent. Questions are constantly being raised that require a definitive answer, or at least standard application, if you want to make sense of it all. To give you some examples: “Where does ‘space’ begin?” “What distinguishes a high-altitude research pilot from a space explorer or a ‘tourist’?’’ ‘‘Are the recent ‘X-Plane’ flights really sub-orbital space-flights?’’ ‘‘In multi-person crews, which one enters ‘space’ first?’’ ‘‘Upon landing, does a Shuttle mission end when the wheels touch the runway, or when they come to a stop?’’ ‘‘Does an EVA start from when the space walker puts a suit on, or when they step out of the airlock?’’ All of these questions find different answers even in official data and this can make a space author’s job that much harder.

What is clear is that when a spacecraft enters orbit, it is assigned a specific orbital object catalogue number. Therefore, one can follow these orbital flights in chronological order, even if the details are open to interpretation. To most crews, ‘‘the mission’’ is one of the most important objectives for their flight and their future careers, and they are assessed by their performance and achievements on ‘‘the mission’’ and its specific objectives or tasks. Usually, records, milestones and ceremonies are not as important to the flight crew as they are to watchers on the ground.

This book, therefore, is not (nor intends to try to be), a definitive record of all manned space flight aspects. Indeed, it is doubtful that such a tome could actually be written, and certainly not in the tight confines of 900 pages. What we have tried to do instead is to present is a single, handy, quick reference source of who did what on which mission, and when they accomplished it, in the 45 years between 1961 and 2006. For more detailed information, other books in this Springer-Praxis series can be referred to, as can those cited in the bibliography of this or other books in the series.

The objective of this book was to keep things simple, so we have therefore focused mostly on orbital missions (or in a few cases, those which were intended for orbital

flight and had left the pad, but never made it into space). The other “sub-orbital”-type missions are listed in context, but are detailed in the opening sections.

By way of introduction, an overview of the methods used to reach space or fly particular types of mission is presented. This is followed by a look at those missions which essentially bridged the gap between aeronautical flight and space flight. Finally, the programmes that have actually been conducted are overviewed, before each orbital space flight is addressed, starting with Yuri Gagarin aboard Vostok 1 in April 1961 and ending with the launch of the 14th resident crew to ISS in September 2006, a span of 45 years. We have also started recording the missions leading towards the 50th anniversary of Gagarin’s flight with the currently manifested missions of 2006-2011, reminding us all that the log is an ever-expanding account of the human exploration of space. As one mission ends, another is being prepared for flight.

In the detail of the main log entries, we have focused on the highlights and achievements for each mission, as this book was always intended to supplement the more in-depth volumes in the Praxis series, as well as other works. It is also intended as a useful starting volume for those who are just becoming interested in human space flight activities and who have not had the opportunity to collect the information from past missions or completed programmes. We also hope that this work will help to generate other, more detailed works on past and current programmes, and in time on those programmes that are even now being planned and will write the future pages of space history – and further entries in the Praxis Log of Manned Space Flight.

Tim Furniss Dave Shayler Mike Shayler September 2006

Assembling a book of this nature would be impossible without a network of fellow space sleuths and journalists. In particular, the assistance over many years of the following friends and colleagues is much appreciated:

• Australia: Colin Burgess

• Europe: Brian Harvey (Ireland), Bart Hendrickx (Belgium) and Bert Vis (The Netherlands)

• UK: Phil Clark, Rex Hall, David Harland, Gordon Hooper, Neville Kidger, Andy Salmon

• USA: Michael Cassutt, John Charles, James Oberg and Asif Siddiqi.

The authors also wish to express their appreciation for the on-going help and support of the various Public Affairs departments of NASA, ESA, and the Russian Space Agency.

The assistance of the Novosti Press Agency and US Information Service was of great help in detailing the pioneering years of human space flight.

Various national and international news organisations were also often consulted, including the publications, Flight International, Aviation Week and Space Technology, and Soviet Weekly.

The staff of the British Interplanetary Society (with its publication Spaceflight) have continued to support our research for many years. We have fond memories of Ken Gatland, past President of the BIS and space flight author, who was an inspiration to many with his documentation of various missions and space activities.

We must express our thanks to Colonel Al Worden (CMP Apollo 15) for his generous foreword.

We also appreciate the help and support of our families during the time it took to compile and prepare this book from its original idea to the finished format.

Last but not least, we appreciate the support and understanding of Clive Hor – wood, Publisher of Praxis, with a project that took a lot out of all of us. Thanks to the staff of Springer-Verlag in both London and New York for post production support; to Neil Shuttlewood and staff at Originator Books for their typesetting skills; to Jim Wilkie for his continued skills in preparing the cover for the project, and to the book printer for the final result.

I was born during the great American Depression, in 1932, at a time when our telephone had a hand crank to call the operator and there were six other families on the line, the bathroom was outdoors, there was no running water and our drinking water came from a hand-dug well in the front yard. Money was tight, but there was a lot of work and fun on my grandparent’s farm. We lived nicely and I can still hear the rain beating on the tin roof at night.

As I grew up, my parents bought a small farm in Jackson, Michigan, and I, along with my five brothers and sisters, lived there during my teen years. One of the most memorable days during those times was the crash of a small airplane behind our house. I was awed by the laid back spirit of the pilots, and thought that would be a great thing to do sometime. The problem was that I did not see myself living my life on a farm. So, when I graduated from high school I searched for the right college to attend, considering that my parents did not have the money to send me to a good one. I ended up going to the United States Military Academy at West Point, graduating there in 1955. Since there was no Air Force Academy at the time, West Point needed to send a third of each class to the Air Force. I elected to go to the Air Force because I thought promotions would be quicker. I found out that was not going to be true, but in the meantime I discovered that I had a real talent for flying, something with which I had very little prior experience.

I never considered a career in the space program, because the possibility of getting in the program was so remote. I flew fighter aircraft for a number of years, and became my squadron’s armament officer because I spent a lot of time in the hanger learning the maintenance business for high performance fighters. While there I rebuilt the armament shop into a very modern work place to motivate the technicians and increase the quality of work. It was a successful effort and the squadron became the role model for others. In fact, I was asked to go to headquarters to help other squadrons do the same thing. Instead, I asked for and received an assignment back to college to learn about guided missiles. While in college I was the operations officer for

all the Air Force pilots, and that fact helped me to get into the Test Pilot School at Farnborough, England. I was transferred to the RAF for a year while at the school, and I returned to the United States to teach at the USAF Research Pilots School at Edwards AFB in California. I still did not believe I had a chance to become an astronaut, but I wanted to be the best test pilot possible. However, NASA had a selection program, and I applied in late 1965. Because of my academic and flight background, I was lucky enough to be selected in April of 1966.

I found out very quickly that one does not become an astronaut by being selected. You have to make a space flight to really and truly be an astronaut, and there was a long training period to finish before assignment to a flight. After that period, which included all the spacecraft operations and special geology training, I was assigned to the support crew of Apollo 9. My job was to check out the spacecraft at the factory, and to complete the build up and check of the hatch that would be used between the Command Module and the Lunar Module. Subsequently, I was assigned to the Apollo 12 back-up crew as Command Module Pilot (CMP), and then to the Apollo 15 prime crew as CMP. Apollo 15 has been proclaimed the most scientific flight of the Apollo program. We trained hard for the extensive science we would accomplish on the flight, and the results were to confirm our efforts were worthwhile.

During the course of our flight training and preparations it was quite clear to us that a vast amount of data was being accumulated. However, we were focused on the flight and what we had to do to make it successful. Once the flight was under way, we concentrated on the science and experiments we were assigned, and how we would keep on the time line so we would not miss anything. At the same time, Mission Control recorded and maintained the down link data for scientific and post-flight analysis. We kept minimal written data on board because of the crush of schedule and the attempt to get all the data we could from both observations and science equipment.

After the flight, all the data was reduced at Johnson Space Center in the form of written reports and Prime Investigator research papers. This process took many months, and in some cases years before any comprehensive knowledge became clear. Because of this process, our knowledge of the Moon has been enhanced tremendously.

Our business was not record keeping, but completing the mission in a successful fashion. Others were responsible for the data and records of our flight. Today, the records are the most important historical evidence of the flight of Apollo 15.

There have been many flights to near space, almost space, and long distance space. They all require a very high level of competence and extraordinary engineering. The X-15, for example, was a magnificent machine, and it opened the way to space. Yuri Gagarin and Al Shepard started the human space initiative, and since then well over two hundred flights have been launched. Each is unique in its own way, with different mission objectives and goals. Humans are curious about what is over the horizon, and they have been exploring for thousands of years to find new continents, new routes to markets, better places to live and work or to find new riches to take back home. Space is also part of our exploration dream, and has been since Jules Verne opened our minds to the possibility of space flight. He even had his lunar crew of three men launch from a site near Cape Kennedy, go to the Moon and return and land in the ocean.

Maybe fact follows science fiction, but here we are today launching crews from Cape Kennedy, and we will soon be sending them back to the Moon.

My journey to space is pretty typical of the American Astronauts. We all had flight and academic experience, but none of us understood what it would take to go into space until we were actually involved in the program. It turned out that hard work was the key, and that training was non-stop before any flight. We also had to maintain a certain degree of calm and fatalism. I remember thinking, the night before launch, that as I talked to my family it just might be the last conversation I would have with them. But the rewards were worth the risk and we did our jobs gladly and freely.

To really understand how all this came about, this book is essential reading. Starting with Yuri Gagarin and following on through the years, this book will educate you on the fast progression of the space programs of several countries. Understanding where we have been will help you understand where we are going. Enjoy!

Colonel Alfred M. Worden USAF Ret.

NASA Group 5 (1966) Pilot Astronaut Command Module Pilot Apollo 15, 1971

|

Offician portrait of Al Worden for Apollo 15

|

To Fallen Heroes

The crews of Apollo 1, Soyuz 1, Soyuz 11, Challenger and Columbia And all the other space explorers who are gone, but never forgotten.

Every journey begins with the first small step. Each small step into space contributes to a larger leap to colonise the cosmos. Each mission’s achievements contribute to the success of the next entry in the world’s manned space flight log book. What started as national rivalry has evolved into international cooperation where each successive space crew can genuinely claim they “came in peace for all mankind.’’

Each log entry was compiled to the same basic layout. The missions are given their official designation but are not numbered chronologically. With variations in defining exactly what constitutes a space flight, and with the increasing tendency for international crews to launch and/or land on separate missions, we have found it far simpler to list the missions in launch sequence and to describe their achievements, than to say superficially which world mission or national mission it was.

The International Designation is the official orbital identification number issued by the International Committee on Space Research (COSPAR). COSPAR gives all satellites and fragments an international designation, based on the year of the launch and the number of successful orbital launches in that calendar year (1 Jan-31 Dec). For example, Apollo 11 received the designation 1969-59A, indicating that it was the 59th orbital launch during the year 1969. The letter code at the end of the designation refers to the type of vehicle launched. Normally, the letter “A” is given to the main instrumented spacecraft; “B” to the rocket; and “C”, “D,” “E” and so on assigned to fragments or ejections. Letters “I” and “O” are not used. If there are more than 24 pieces (such as debris from an explosion), the sequence after “Z” becomes “AA, AB and so on up to “AZ”, and then “BA”, “BB”, etc. For this volume, we have listed only the “A” designations. These items are tracked by the North American Aerospace Defense command (NORAD) which supplies orbital data elements (via NASA) on all traceable satellites – very useful in the identification of potential space debris impacts. In the years 1957-1962, a different system was used, with designations utilising the symbols of the 24 letters of the Greek alphabet. For the years 1961-1962 in this volume, we iterate these Greek letters in full for clarity.

The launch date, launch site and landing date and site are given as local time; we have not tried to convert to GMT or UT. We have omitted local times for clarity wherever possible, although for some of the more historic missions in the days before

data was accessible at the click of a mouse button, we have kept some of this data in as a useful reference point. The launch vehicle details have been included where known. It is likely that further data will come to light in future years that will enable us to give a more complete picture of such information.

Durations are given from official sources (NASA or Soviet/Russian) and for Shuttle missions, this is from lift-off to wheel stop at the end of its runway landing. Callsigns (when used) and mission objectives are also presented for information.

Crew details are for the PRIME, or flight, crew only and are presented in the order commander; pilot; then specialists in numerical sequence. Each crew entry lists their full name, age at time of launch, military affiliation or civilian, position on this crew, the number of times they have flown into space, and their previous missions for quick cross-reference. All crew members are either American (astronauts) or Soviet (cosmonauts) unless their nationality is noted.

The flight log records key mission events and, where necessary, pre- and postflight operations. When an X-15, sub-orbital or X-prize flight occurred, it is mentioned briefly for continuity in the main text. The details of such missions are included in the opening sections.

When a crew is launched on one mission and returns on another, their whole flight is reported under their launch mission and only briefly mentioned under their landing mission. Therefore, when a space station crew is launched with a core crew of two with a third passenger, the passenger’s activities are recorded along with that of the core space station crew in the same “mission log.’’ This process evolved during the Mir programme, in which guest cosmonauts would fly with an expedition crew who remained on the station, while the guest returned home after about a week in the older spacecraft and with the previous core crew.

On ISS, there have been several occurrences of a complete ISS core crew being launched as “passengers’’ on a Shuttle mission, and landing “as passengers” on a separate Shuttle mission. Here, we have covered the launch of the Shuttle mission separately, followed by the resident crew’s activities as second entry and the landing mission as a third.

Milestones are significant events, achievements and celebrations relating to that crew or mission’s flight into space.

We have not provided references as there are just so many to collate all this data from. The most referred to sources are listed in the bibliography and further details of sources of information can be obtained from the authors if so desired.

Following these guidelines, the Quest for Space section covers those missions that did not reach orbital flight but are part of the story of human space exploration: the 13 launches between 1962 and 1968 of the X-15 that exceeded the then-designated 50 mile (80 km) limit; the two Mercury Redstone sub-orbital missions in 1961; the Apollo 1 pad fire that claimed the lives of three American astronauts on 27 January 1967 just two weeks prior to their planned mission; the Soyuz T10-1 pad abort which occurred just seconds prior to the planned lift-off; and the recent X-Prize flights of Spaceship 1 in 2004.

The launch abort of the Soyuz 18-1 mission in April 1975 is included in the log entries, as is the loss of Challenger during the STS 51-L mission in January 1986. Both of these missions had launched and were “missions in progress” when they encountered their specific difficulties. Had they continued in their planned trajectory, both would have reached orbit.

Wherever possible, we have followed the metric system of weights and distances.

The Appendices review orbital space flight between 1961 and 2006; the cumulative time that astronauts and cosmonauts have spent in space in the order of most experienced; and a brief timeline of historic and key missions in the exploration of space.

Call signs: In the early days of manned space flight, there was no requirement to identify one spacecraft from another because there was never more than one in orbit at a time. Mercury astronauts, however, following the tradition of pilots naming their aircraft, assigned names to their Mercury capsules, adding the number 7 to signify the seven original Mercury astronauts. Thus, the Mercury missions were also known as Friendship 7, Sigma 7, Aurora 7 etc. Had Deke Slayton flown, he would have used the call sign Delta 7

The Gemini spacecraft used the spacecraft’s number as a call sign (though for a while the Gemini 4 astronauts tried to assign the name “American Eagle’’ to the flight and it was also known as “Little Eva’’ – for the EVA or spacewalk). The early Apollo missions also did not require a call sign but by now, distinctive mission emblems were being worn by the crews (from Gemini 5). These have become a traditional part of any manned space flight and are descriptive and colourful. The names of the crew are usually displayed on the emblem, though not always. Programme emblems, activity emblems (such as the EVA badge), payload and support teams emblems and (from 1978) Astronaut Group selection emblems have evolved from these. Russian cosmonauts and Chinese yuhangyuans have displayed similar types of emblems.

From Apollo 9 and the first manned flight test of the Lunar Module, it was necessary to be able to clearly identify both the Command and Lunar modules during radio conversations as both would be flying separately at some stage during the mission, with members of the crew aboard each module. Thus, the Command Module became “Gumdrop” and the Lunar Module “Spider.” This practice continued throughout Apollo up to Apollo 17. For Skylab and the American Apollo spacecraft used during the ASTP flight, the crews used the call signs “Skylab” or “Apollo”. When the Americans began to fly the Space Shuttle in 1981, the call sign became the name of the individual orbiter that was being used, as each has its own moniker.

For the Soviet and Russian missions, each pilot cosmonaut chose their own call sign. When in command of a mission, they adopted that call sign for the flight, with other crewmembers appending “2” or “3” to it to identify themselves individually during the mission. When engineer cosmonauts began to fly as mission commanders in 1978, they too were assigned personal call signs, and resident Soviet/Russian space station crews were also known by the call sign of the commander. For ISS missions, it appears that cosmonaut Soyuz TMA commander call signs are used for contact over Russian ground stations and during flights of the Soyuz spacecraft independent of the ISS. It is unclear if Chinese Shenzhou missions or yuhangyuans have adapted a call sign.

| | | | |

1997-039A 7 August 1997

1997-039A 7 August 1997