Foreword

I was born during the great American Depression, in 1932, at a time when our telephone had a hand crank to call the operator and there were six other families on the line, the bathroom was outdoors, there was no running water and our drinking water came from a hand-dug well in the front yard. Money was tight, but there was a lot of work and fun on my grandparent’s farm. We lived nicely and I can still hear the rain beating on the tin roof at night.

As I grew up, my parents bought a small farm in Jackson, Michigan, and I, along with my five brothers and sisters, lived there during my teen years. One of the most memorable days during those times was the crash of a small airplane behind our house. I was awed by the laid back spirit of the pilots, and thought that would be a great thing to do sometime. The problem was that I did not see myself living my life on a farm. So, when I graduated from high school I searched for the right college to attend, considering that my parents did not have the money to send me to a good one. I ended up going to the United States Military Academy at West Point, graduating there in 1955. Since there was no Air Force Academy at the time, West Point needed to send a third of each class to the Air Force. I elected to go to the Air Force because I thought promotions would be quicker. I found out that was not going to be true, but in the meantime I discovered that I had a real talent for flying, something with which I had very little prior experience.

I never considered a career in the space program, because the possibility of getting in the program was so remote. I flew fighter aircraft for a number of years, and became my squadron’s armament officer because I spent a lot of time in the hanger learning the maintenance business for high performance fighters. While there I rebuilt the armament shop into a very modern work place to motivate the technicians and increase the quality of work. It was a successful effort and the squadron became the role model for others. In fact, I was asked to go to headquarters to help other squadrons do the same thing. Instead, I asked for and received an assignment back to college to learn about guided missiles. While in college I was the operations officer for

all the Air Force pilots, and that fact helped me to get into the Test Pilot School at Farnborough, England. I was transferred to the RAF for a year while at the school, and I returned to the United States to teach at the USAF Research Pilots School at Edwards AFB in California. I still did not believe I had a chance to become an astronaut, but I wanted to be the best test pilot possible. However, NASA had a selection program, and I applied in late 1965. Because of my academic and flight background, I was lucky enough to be selected in April of 1966.

I found out very quickly that one does not become an astronaut by being selected. You have to make a space flight to really and truly be an astronaut, and there was a long training period to finish before assignment to a flight. After that period, which included all the spacecraft operations and special geology training, I was assigned to the support crew of Apollo 9. My job was to check out the spacecraft at the factory, and to complete the build up and check of the hatch that would be used between the Command Module and the Lunar Module. Subsequently, I was assigned to the Apollo 12 back-up crew as Command Module Pilot (CMP), and then to the Apollo 15 prime crew as CMP. Apollo 15 has been proclaimed the most scientific flight of the Apollo program. We trained hard for the extensive science we would accomplish on the flight, and the results were to confirm our efforts were worthwhile.

During the course of our flight training and preparations it was quite clear to us that a vast amount of data was being accumulated. However, we were focused on the flight and what we had to do to make it successful. Once the flight was under way, we concentrated on the science and experiments we were assigned, and how we would keep on the time line so we would not miss anything. At the same time, Mission Control recorded and maintained the down link data for scientific and post-flight analysis. We kept minimal written data on board because of the crush of schedule and the attempt to get all the data we could from both observations and science equipment.

After the flight, all the data was reduced at Johnson Space Center in the form of written reports and Prime Investigator research papers. This process took many months, and in some cases years before any comprehensive knowledge became clear. Because of this process, our knowledge of the Moon has been enhanced tremendously.

Our business was not record keeping, but completing the mission in a successful fashion. Others were responsible for the data and records of our flight. Today, the records are the most important historical evidence of the flight of Apollo 15.

There have been many flights to near space, almost space, and long distance space. They all require a very high level of competence and extraordinary engineering. The X-15, for example, was a magnificent machine, and it opened the way to space. Yuri Gagarin and Al Shepard started the human space initiative, and since then well over two hundred flights have been launched. Each is unique in its own way, with different mission objectives and goals. Humans are curious about what is over the horizon, and they have been exploring for thousands of years to find new continents, new routes to markets, better places to live and work or to find new riches to take back home. Space is also part of our exploration dream, and has been since Jules Verne opened our minds to the possibility of space flight. He even had his lunar crew of three men launch from a site near Cape Kennedy, go to the Moon and return and land in the ocean.

Maybe fact follows science fiction, but here we are today launching crews from Cape Kennedy, and we will soon be sending them back to the Moon.

My journey to space is pretty typical of the American Astronauts. We all had flight and academic experience, but none of us understood what it would take to go into space until we were actually involved in the program. It turned out that hard work was the key, and that training was non-stop before any flight. We also had to maintain a certain degree of calm and fatalism. I remember thinking, the night before launch, that as I talked to my family it just might be the last conversation I would have with them. But the rewards were worth the risk and we did our jobs gladly and freely.

To really understand how all this came about, this book is essential reading. Starting with Yuri Gagarin and following on through the years, this book will educate you on the fast progression of the space programs of several countries. Understanding where we have been will help you understand where we are going. Enjoy!

Colonel Alfred M. Worden USAF Ret.

NASA Group 5 (1966) Pilot Astronaut Command Module Pilot Apollo 15, 1971

|

Offician portrait of Al Worden for Apollo 15 |

To Fallen Heroes

The crews of Apollo 1, Soyuz 1, Soyuz 11, Challenger and Columbia And all the other space explorers who are gone, but never forgotten.

|

|

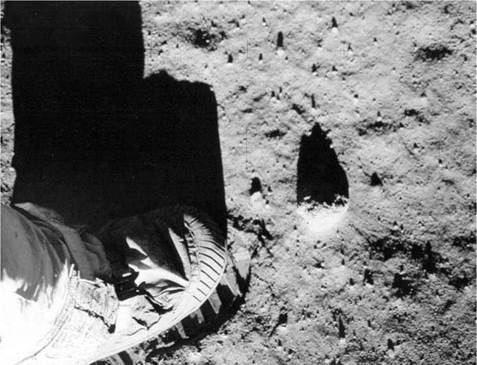

Every journey begins with the first small step. Each small step into space contributes to a larger leap to colonise the cosmos. Each mission’s achievements contribute to the success of the next entry in the world’s manned space flight log book. What started as national rivalry has evolved into international cooperation where each successive space crew can genuinely claim they “came in peace for all mankind.’’