. SOYUZ TM18

Flight Crew

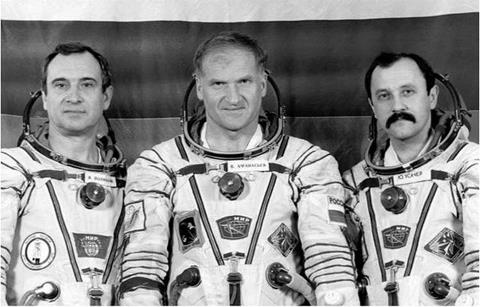

AFANASYEV, Viktor Mikhailovich, 45, Russian Air Force, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM11/Mir EO-8 (1990)

USACHEV, Yuri Vladimirovich, 36, civilian NPO Energiya, flight engineer POLYAKOV, Valery Vladimirovich, 51, civilian, cosmonaut researcher, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz TM6/Mir EO-3/4 (1988)

Flight Log

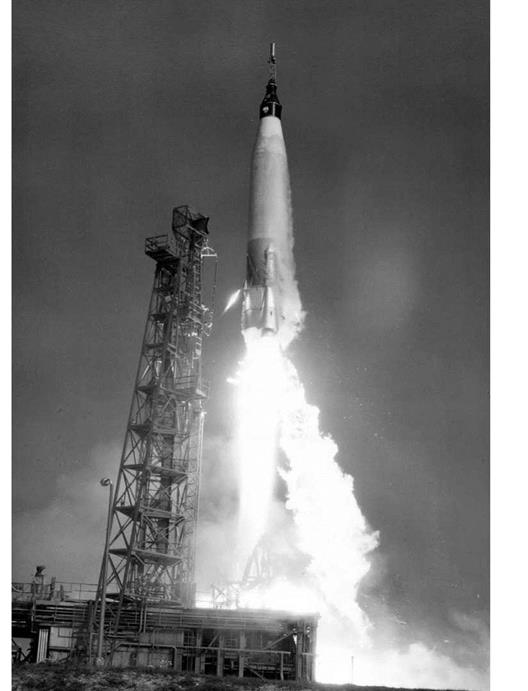

The launch of TM18 had been delayed due to the unavailability of the more powerful Soyuz U launch vehicle to lift the three-man crew. The flight of Polyakov was a logical step in the Russian quest for long-duration space flight experience and medical data. When Polyakov devised the programme for a second space flight, he aimed for an 18-month duration, but delays forced him to curtail the duration to 14 months, as he could not remain aboard Mir when the first NASA astronaut arrived on the station, which at the time was planned for early 1995. Though he carried out his own research programme, Polyakov still participated in other tasks, working with three different resident crews until his return in March 1995.

One of the first tasks on this mission was to relocate the Soyuz TM18 ferry from the aft port to the front port of the base block, which occurred on 24 January. During the short flight, the crew flew past the Kristall module and reported only minor scratches on its hull from where TM17 had struck it. Work for this resident crew was again limited by plans for the upcoming American docking missions, particularly the integration of Soyuz and Progress launches and amendments to subsequent

|

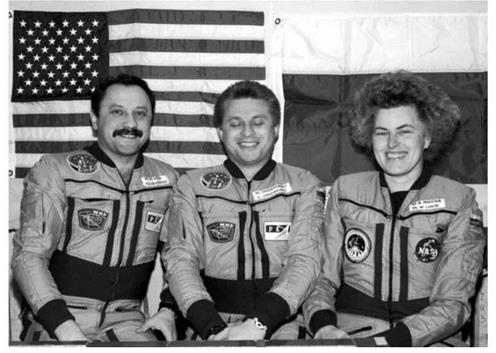

Record-breaker Polyakov (left) with the rest of the Soyuz TM18 crew, Afanasyev (centre) and Usachev |

resident crews to accommodate the joint programme with the Americans. At the time of Afanasyev and Usachev’s flight, this national and international coordination was difficult to implement, mainly due to the lack of funds, and soon the launch of the next resident crew had slipped from April to July. However, the EO-15 crew continued their research along the lines of previous resident crews, but also conducted medical and technical experiments sponsored by German institutes. Polyakov had also supplemented the science payload with smaller items brought up in his personal baggage on TM18.

In February, Sergei Krikalev was launched on the American Shuttle mission STS – 60, the first time that cosmonauts had been in space at the same time on different missions in spacecraft belonging to different nations. The following month, Progress M22 was also delayed for three days from 19 March when heavy snowfall at the launch site resulted in snow drifts covering the rail network to a depth of up to seven metres, making it impossible to move the spacecraft and its booster from the assembly building to the launch pad.

At the end of March, the cosmonauts on Mir participated in an experiment with a Swedish satellite called Freja, designed to study space plasma and magnetosphere physics in Earth’s magnetosphere and ionosphere. Launched in 1992 by the Chinese, Freja was located 1,770 km above the Alaskan coast when the crew of Mir, situated 383 km above the Pacific south of Alaska, fired an electron beam gun at it. At the time of the experiment, a Canadian ground station monitored the operation. Despite its scientific aim of determining how charged particle beams were scattered in the atmosphere, the media still reported the experiment as a test of Russian “Star Wars” weapons.

The difficulties that the post-Soviet Russia was undergoing were brought home to the cosmonauts aboard Mir in May, during unloading of the Progress M23 re-supply craft. They found that some of the food containers intended for the orbiting crew had been tampered with by ground staff, and items that should have been there were missing.

Milestones

166th manned space flight

77th Russian manned space flight

18th manned Mir mission

15th Mir resident crew

70th manned Soyuz mission

17th manned Soyuz TM mission

1st Mir resident mission without scheduled EVAs

Polyakov sets world endurance record for one flight of 437 days 17hrs, and a career record of 678 days 16hrs on two flights Polyakov celebrates his 52nd birthday in space (27 Apr)

. SOYUZ TM23Flight Crew ONUFRIYENKO, Yuri Ivanovich, 35, Russian Air Force, commander USACHEV, Yuri Vladimirovich, 38, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM18 (1994) Flight Log After taking over from the EO-20 crew, the next resident crew for Mir had a busy programme of activities planned for their mission. They were to perform six EVAs, support the arrival of the final Mir science module (Priroda), and work with the second American to live on Mir, Shannon Lucid. In addition there was a change of cosmonauts in the subsequent resident crew and an extension both to Lucid’s mission and to the cosmonauts’ own stay on Mir. The “two Yuris’’, as the press called them, were expecting to conduct a four-and – a-half month residency, but by July, continued problems over the construction of Soyuz rockets at the Samara factory meant that the next mission would have to slip and the cosmonauts were told they would have to fly a six-month mission. Their first EVA (15 May, 5 hours 52 minutes) featured the installation of a second Strela boom to allow easier movement to the repositioned Kristall module. Other EVAs would be performed after the arrival of STS-76 and the transfer of Shannon Lucid to the station. Shannon Lucid had arrived at Mir on 24 March for what was planned as a 140-day mission but, again in July, following technical problems with the Shuttle SRBs and the decision to replace those assigned to STS-79 (the mission that would bring her home), her own residency was extended, eventually reaching 188 days, and setting a new US endurance record both for a single mission and for a career total. During the other EVAs conducted by the two Russian cosmonauts, Lucid would remain inside the station, monitoring the activities of her two colleagues.

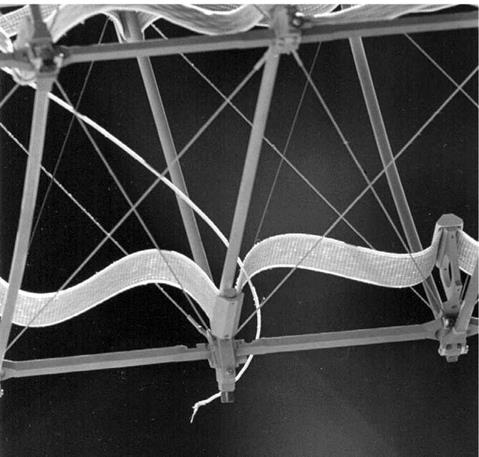

The science module Priroda arrived on 26 April, and the following day was transferred to the left radial (+Z) port, completing the Mir complex. The module contained an array of remote-sensing instruments for ecological and environmental investigations. It also included over 700 kg of NASA equipment and experiments for the American resident crew members to use during their science programmes. Part of the task of the EO-21 resident crew was to begin changing the inside of the new module from its launch configuration to allow it to be used on orbit over the next few years. The two Yuri’s conducted their other five EVAs from mid-May to mid-June (21 May for 5 hours 20 minutes; 24 May for 5 hours 43 minutes; 30 May for 4 hours 20 minutes; 6 Jun for 3 hours 34 minutes; and 14 Jun for 5 hours 42 minutes). Their activities included the installation of the Mir Cooperative Solar Array, the installation of a multi-spectral scanner, retrieval and installation of sample cassettes, the assembly of the Stombus (Ferma-3) 5.9-metre truss, and the deployment of a Symmetric Aperture Radar antenna. They also constructed (over two of the EVAs) a 1.2-m replica Pepsi can from aluminium struts and decorated nylon sheets. They filmed each other near the replica and then disassembled it for return to Earth. The video footage was to be used in a PepsiCo commercial campaign. Towards the end of their mission, the two cosmonauts handed over to the 22nd resident crew, who had arrived on 19 August. Also arriving with the new crew was French cosmonaut Claudie Andre-Deshays, who would return to Earth with the EO-21 cosmonauts two weeks later. For a while, six cosmonauts were on board the station, and Usachev noted the increase in noise levels aboard the station, though it still seemed roomy enough for now. Milestones 186th manned space flight 82nd Russian manned space flight 75th manned Soyuz mission 22nd manned Soyuz TM mission 28th Russian and 61st flight with EVA operations 21st Mir resident crew

Flight Crew ALLEN, Andrew Michael, 40, USMC, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-46 (1992); STS-62 (1994) HOROWITZ, Scott Jay, USAF, pilot HOFFMAN, Jeffrey Alan, civilian, mission specialist 1, 5th mission Previous missions: STS 51-D (1985); STS-35 (1990); STS-46 (1992); STS-61 (1993) CHELI, Maurizio, Italian Air Force, ESA mission specialist 2 NICOLLIER, Claude, Swiss Air Force, ESA, mission specialist 3, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-46 (1992); STS-61 (1993) CHANG-DIAZ, Franklin Ramon, 45, civilian, mission specialist 4, payload commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS 61-C (1986); STS-34 (1989); STS-46 (1992) GUIDONI, Umberto, 41, civilian, Italian payload specialist 1 Flight Log This mission was the re-flight of the US/Italian Tethered Satellite System that was previously flown on STS-46 in 1992. The crew worked a two-shift system. Allen, Horowitz, Cheli and Guidoni worked the Red Shift while Hoffman, Nicollier and Chang-Diaz formed the Blue Shift. Allen and Hoffman were also designated the White Shift, allowing them to work between shifts as necessary. The deployment of TSS-1R was delayed on STS-75 for 24 hours so that the flight crew could troubleshoot problems with the system’s computers. On FD 3, the tether was extended almost to its maximum 20.5 km length and the satellite was sending back excellent data when the tether suddenly snapped (at 19.7 km) without prior warning. Orbital parameters at the time meant that the satellite separated from Columbia and the crew were placed in no danger. The day after the loss of the satellite, the remaining tether was reeled in and

the deployer retracted. Tether Optical Phenomenon operations continued through to FD 14 and there was some consideration given to a rendezvous and possible retrieval of the free-flying satellite. However, there was insufficient propellant aboard and projections precluded any detailed plans for an attempt from being pursued. Despite this loss, the satellite had recorded useful data for five hours up to the point of separation. Analysis of the data revealed that voltages as high as 3,500 volts developed across the tether, and this achieved current levels of 480 milliamps. In addition, scientists received important data on how satellite thruster gas interacted with Earth’s ionosphere, measurements of ionised shock waves around a satellite for the first time, and data on plasma wakes created by the movement of a body through the electrically charged ionosphere. Some experiments were also conducted using the free-flying satellite and its attached tether prior to its re-entry and destruction in the upper atmosphere. Despite the loss, the data gathered during the TSS-1R operation resulted in a number of space physics and plasma theories being revised or overturned. The other major payload of this mission was the USMP-3 package, which included re-flights of US and international experiments. Most of the operation of USMP experiments was via telescience, with principle investigators located at the Marshall Space Flight Center Spacelab Mission Operations Control Center in Huntsville, Alabama. There were five major experiments in materials science and a glove box on the mid-deck was used to perform a series of combustion experiments to better understand combustion processes and improve fire safety for the ISS. Protein crystal growth experiments included processing nine proteins extracted from the tropical rain forests of Costa Rica into crystals to further the understanding of their molecular structures. This was a joint US, Costa Rican and Chilean experiment, with application for the pharmaceutical treatment of Chagas Disease, an incurable ailment that affects over 15 million people in Latin America. The landing of Columbia on 9 March occurred after a 24-hour waive-off due to unfavourable weather conditions. The first attempt on 9 March was also abandoned due to bad weather, but it cleared to allow a landing at the Cape at the second opportunity. On FD 7, Hoffman surpassed Kathy Thornton’s Shuttle space flight record of 978 hours 18 minutes, and by the end of the mission both he and Chang-Diaz had achieved over 1,000 hours cumulative flight time aboard the Shuttle. In June 1996, a joint NASA and ASI (the Italian Space Agency) investigation board report was released, which determined that the tether failed as a result of “arcing and burning of the tether, which led to a tensile failure after a significant portion of the tether had burned away.’’ The board concluded that external penetration (but not space debris or micrometeoroids) or a defect in the tether caused a breach in the layer of insulation surrounding the conductor. This would have allowed a current to jump or arc from the copper wire in the tether to a nearby electrical ground. By examining the data and the frayed end of the tether, the board concluded that there was nothing to preclude any follow-on mission, after sufficient improvements had been made to ensure that the problem would not recur. The data received from the abbreviated experiments indicated that, on the whole, the major objectives had been met, the programme was mostly successful, and it was viable for future development. Milestones 187th manned space flight 105th US manned space flight 75th Shuttle mission 19th flight of Columbia 2nd flight of TSS 7th EDO mission

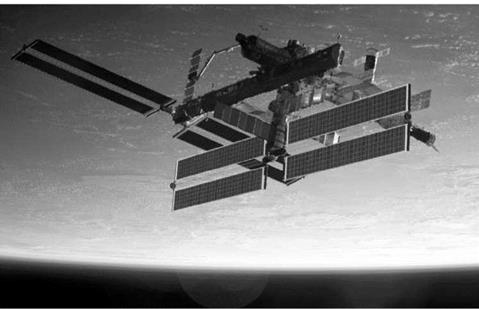

Flight Crew CABANA, Robert Donald, 49, USMC, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-41 (1990); STS-53 (1992); STS-65 (1994) STURCKOW, Frederick Wilford, 37, USMC, pilot ROSS, Jerry Lynn, 50, USAF, mission specialist 1, 6th mission Previous missions: STS 61-C (1985); STS-27 (1988); STS-37 (1997); STS-55 (1993); STS-74 (1995) CURRIE, Nancy Jane, 39, US Army, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-57 (1993); STS-70 (1995) NEWMAN, James Hanson, 42, civilian, mission specialist 3, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-51 (1993); STS-69 (1995) KRIKALEV, Sergei Konstantinovich, 40, civilian, Russian, mission specialist 5, 4th mission Previous missions: Soyuz TM7 (1988); Soyuz TM12 (1991); STS-60 (1994) Flight Log This mission initiated the construction of the International Space Station (ISS), a project which had long been proposed but which so often looked as though it would never become reality. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan had challenged NASA to build a space station within a decade. An international team assembled to accomplish the feat, but an over-complicated and expensive design, coupled with the loss of Challenger and doubts over the reliability of the Shuttle had added years to the project. By 1993, the idea was still only on the drawing board and in mock-ups. After several redesigns, a new partnership with Russia helped put the programme back on track. The series of Shuttle-Mir dockings proved that the Shuttle was perfectly capable of doing what it was originally envisioned for back in 1969 – servicing and supplying a space station. A simplified station design helped focus

the ISS project to the point where the first element of the station was launched on 20 November 1998. This was not an American element, however, but the Russian FGB Zarya (“Dawn”), designed to provide electrical power, attitude control and computer command and later serve as a fuel depot and storage facility. The next element of the station would be the link between the US and the Russian elements. Known as Node 1 (“Unity”), it featured six docking ports that would enable the facility to be further expanded. Unity was the primary payload of STS-88, the first American ISS Shuttle mission, which would use the RMS to attach the module to the forward docking port of Zarya. The launch of STS-88 was postponed by 24 hours on 3 December due to problems with hydraulic system number 1. By the time the problem was cleared, it was too late in the launch process to initiate the final countdown, so the first American element had to wait until the following day to lift off without further incident. During the approach to Zarya, the crew used their time to prepare Unity by testing the RMS. On 5 December, they attached the end effector to the node, lifting it out of the rear of the payload bay and relocating it in the front of the payload bay along with the Shuttle docking system. This would later allow the crew access through internal hatches from the crew compartment of Endeavour into Unity and on into Zarya. The attachment of Unity to Zarya occurred on 6 December, using the RMS to grasp a grapple feature on Zarya and using the Shuttle’s engines to gently nudge the Unity docking system on to that of Zarya. The embryonic ISS configuration was created. After powering up Unity and checking the integrity of the docking seals and internal atmospheres, the hatches were opened, allowing Cabana and Krikalev to symbolically float into ISS together for the first time. During the three EVAs (7 Dec for 7 hours 21 minutes; 9 Dec for 7 hours 2 minutes; and 12 Dec for 6 hours 59 minutes), Ross (EV1) and Newman (EV2) removed launch restraint pins on the four hatches on Unity that would be used in future operations, nudged two stuck antennas on Zarya into position, installed sunshades over Unity’s data relay boxes, disconnected the umbilicals that were used to mate the units, and installed a handrail, a tool bag and an S-Band communication system. They also tested the SAFER units. Inside Zarya, Krikalev and Currie replaced a faulty unit, inspected the inside of the module and removed some launch bolts and restraints. The undocking from ISS took place on 13 December. After a fly-around photographic inspection, the crew prepared for landing, having completed one of the most important and critical Shuttle flights. One of the largest international construction projects in history – and certainly the largest off the Earth – had begun. The STS crew called themselves “Dog Crew 3’’, since two of them had flown on previous “Dog Crews’’. Thus, the crew were known as “Mighty Dog’’ (Cabana), “Devil Dog’’ (Sturckow), “Hooch” (Ross), “Laika” (Currie), “Pluto’’ (Newman) and “Spotnik” (Krikalev). Milestones 210th manned space flight 123rd US manned space flight 93rd Shuttle mission 41st US and 72nd flight with EVA operations 13th flight of Endeavour 1st Shuttle ISS mission 1st Endeavour ISS mission STS-109 |

|

Int. Designation |

2002-010A |

|

Launched |

1 March 2002 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

12 March 2002 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-102 Columbia/ET-112/SRB BI-111/SSME #1 2056; |

|

#2 2053; #3 2047 |

|

|

Duration |

10 days 22 hrs 11 min 9 sec |

|

Call sign |

Columbia |

|

Objective |

4th Hubble Service Mission (HST SM 3B) |

Flight Crew

ALTMAN, Scott Douglas, 42, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-90 (1998); STS-106 (2000)

CAREY, Duane Gene, 44, USAF, pilot

GRUNSFELD, John Mace, 43, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander, 4th mission

Previous missions: STS-67 (1995); STS-81 (1997); STS-103 (1999)

CURRIE, Nancy Jane, 43, US Army, mission specialist 2, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-57 (1993); STS-70 (1995); STS-88 (1998) LINNEHAN, Richard Michael, 44, civilian, mission specialist 3, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-78 (1996); STS-90 (1998)

NEWMAN, James Hansen, 45, civilian, mission specialist 4, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-51 (1993); STS-69 (1995); STS-88 (1998) MASSIMINO, Michael James, 39, civilian, mission specialist 5

Flight Log

The scheduled launch on 28 February was postponed 24 hours before tanking operations commenced when adverse weather conditions threatened launch criteria. Waiting 24 hours also gave the launch team the option of back-to-back launch opportunities, but they did not need them as launch occurred without delay on 1 March. Following the launch, controllers noted a degradation of the flow rate in one of two freon coolant loops which help dissipate heat from the orbiter. After a management review, the mission was given a “go” for its full duration. The problem had no impact on the crew’s activities and the vehicle de-orbited nominally.

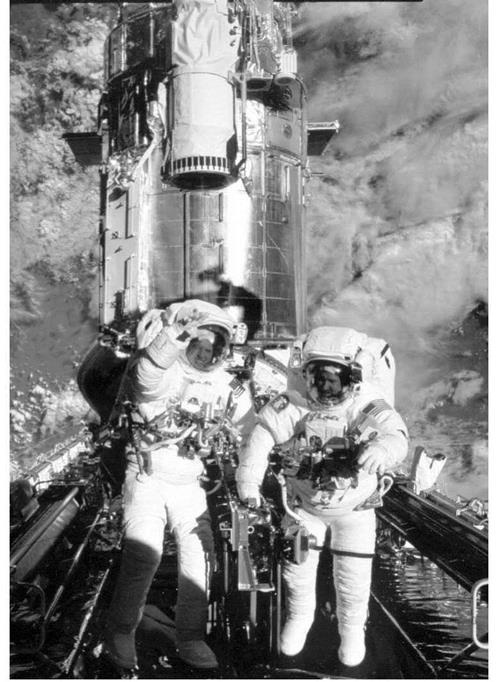

Hubble was grappled and secured in the payload bay by the RMS on 2 March (FD 2). A series of five EVAs were completed by the crew, working in pairs. Grunsfeld (EV1) and Linnehan (EV2) completed EVAs 1, 3 and 5, while Newman (EV3) and Massimino (EV4) completed EVAs 2 and 4. When not performing an EVA, the resting

|

team also acted as IV crew for those who were outside, and serviced, cleaned and prepared their own equipment ready for their next excursion. Each EVA was supported by Nancy Currie operating the RMS, with Altman and Carey photo – documenting the activities.

During the first EVA (4 Mar for 7 hours 1 minute), the astronauts removed the older starboard solar array from the telescope (attached during STS-61 in December 1993) and installed a new third-generation array. The old (retracted) array was then stowed in Columbia’s payload bay for return to Earth for analysis of its condition after nine years in space. During EVA 2 (5 Mar for 7 hours 16 minutes), the new port array was installed, together with a new Reaction Wheel Assembly after the removal of the older array. The astronauts also installed thermal blankets on Bay 6, door stop extensions on Bay 5 and foot restraints to assist with the next EVA. EVA 2 also included a test of bolts located on the aft shroud doors. The lower two bolts were found to need replacing, which they accomplished successfully. EVA 3 (6 Mar for 6 hours 48 minutes) was delayed by a fault in Grunsfeld’s suit, but after changing the HUT, they continued with the EVA programme. This included replacing the Power Control Unit (PCU) with a new unit capable of handling 20 per cent of power output generated from the new arrays. The extracted PCU was the original launched on the telescope in 1990, and this operation required the telescope to be powered down. This was the first time since its launch that Hubble had been turned off. The astronauts removed all 36 connectors to the old PCU and stowed it in the payload bay before attaching the new unit within 90 minutes. One hour later, the new unit passed its tests and Hubble came back to life. EVA 4 (7 Mar for 7 hours 18 minutes) completed the first science instrument upgrade of the mission by removing the last original instrument on the telescope, the Faint Object Camera, and installing the Advanced Camera for Surveys. They also installed the first element of an environmental cooling system, called the Electronics Support Module (ESM). The rest of the system would be installed the following day. The final EVA (8 Mar for 7 hours 32 minutes) saw the installation of the Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS) in the aft shroud and the connection of cables to the ESM. They also installed the Cooling System Radiator on the outside of Hubble and fed radiator wires through the bottom of the telescope to connections on NICMOS.

Hubble was released by the RMS on 9 March (FD 9) and the next day was a rest day for the astronauts. During the day, they took the opportunity to speak with the ISS-4 crew (Yuri Onufriyenko, Carl Walz and Dan Bursch). FD 11 saw a full systems check before landing at the first opportunity at the Cape on FD 12, rounding out a highly successful mission. At this time, there was a further Hubble service mission on the manifest (HST SM #4) in 2004 or 2005, with a close-out mission in 2010. The options of either bringing the telescope back to Earth for eventual display in a museum or leaving it in orbit, boosted to a higher apogee to reduce atmospheric drag, were still being considered when Columbia was lost in February 2003. It looked as though Hubble was likely be abandoned when its systems eventually failed, but there was also growing support both inside and outside of NASA to devote one Shuttle mission to revisit the telescope before the Shuttle fleet is retired in 2010. In

October 2006, a return to Hubble was authorised for 2008 due to public and scientific demand for keeping the telescope working for as long as possible.

Milestones

230th manned space flight

138th US manned space flight

108th Shuttle mission

27th flight of Columbia

52nd US and 85th flight with EVA operations

4th Hubble service mission (3B)

EVA duration record for single Shuttle mission (35hrs 55 min)

STS-115 |

|

Int. Designation |

2006-036A |

|

Launched |

9 September 2006 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

21 September 2006 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-104 Atlantis/ET-118/SRB BI-127/SSME: #1 2044, #2 2048; #3 2047 |

|

Duration |

11 days 19 hrs 7 min 24 sec |

|

Call sign |

Atlantis |

|

Objective |

ISS assembly mission 12A; delivery and installation of P3/P4 Truss |

Flight Crew

JETT, Brent, 47, USN, commander, 4th mission

Previous missions: STS-72 (1996); STS-81 (1997); STS-97 (2000)

FERGUSON, Chris, 44, USN, pilot

TANNER, Joe, 56, civilian, mission specialist 1, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-66 (1994); STS-82 (1997); STS-97 (2000) BURBANK, Dan, 45, USCG, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-106 (2000)

STEFANYSHYN-PIPER, Heidemarie, 43, USN, mission specialist 3 MACLEAN, Steve, 51, civilian, Canadian mission specialist 4

Flight Log

Set for a 29 August launch, the lift-off for the STS-115 mission to resume space station construction was postponed due to the proximity of tropical storm Ernesto. A decision was then made to roll back the STS-115 stack into the protection of the VAB for the duration of the storm as it passed KSC. This had a scheduling impact for the Russian launch of Soyuz TMA9 in September, but later the same day, NASA managers decided to reverse the decision and began moving the Shuttle back to the pad as weather predictions improved. On 6 September, a problem with Fuel Cell #1 in Atlantis was noted when a voltage spike in the coolant pump was recorded, threatening the planned 8 September launch. Analysis indicated that this was not a problem that would prevent the launch, but when a fuel cut-off sensor in the ET caused concern during the final minutes of the count, the mission was postponed 24 hours at the T — 9 minute mark. After a nominal performance during tests, the launch was given the all clear to proceed, which it did without further incident.

The delay had resulted in a short postponement of the launch of Soyuz TMA9 to the station and the shortening of the STS-115 mission by a day.

|

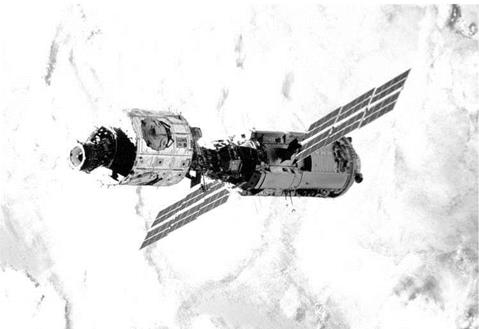

Displaying a new set of wings, this photograph of ISS taken from the departing Shuttle reveals the newly-installed solar arrays delivered and installed by the crew of STS-115 |

The first day in orbit found the crew preparing equipment for the docking and EVA activities, as well as inspecting the thermal protection system on the orbiter. After analysis on the ground, no significant damage was found. Prior to docking on 11 September, the orbiter was flipped to allow the ISS-13 crew to observe and photodocument the TPS. Less than two hours after docking, the crew entered the station for the first time. At the end of the day, the first EVA crew of Tanner (EV1) and Stefanyshyn-Piper (EV2) “camped-out” for the night in the Quest airlock to purge their bloodstreams of nitrogen, which would shorten EVA preparations the next day. This pair completed the first and third EVAs of the mission, with Burbank (EV3) and Canadian Steve MacLean (EV4) completing the second EVA. All three EVAs (12 Sep for 6 hours 26 minutes; 13 Sep for 7 hours 11 minutes; and 15 Sep for 6 hours 42 minutes) were associated with the installation of the P3/P4 Truss and the deployment of the solar arrays and radiators.

No focused inspection of the Atlantis TPS was required after detailed analysis of the images from the crew, RMS and station inspections, so after the first two EVAs were completed, the crew rested for a couple of days and turned their attention to the transfer of logistics to and from the station. Such was the success of the first two EVAs, the crew managed to complete several get-ahead tasks along with their primary objectives.

On 17 September, Atlantis undocked from ISS after a visit lasting six days. Early the next morning, as the Shuttle began preparations for the return to Earth, Soyuz TMA9 was launched from Baikonur. With 12 space explorers in orbit at the same time

on three different vehicles (six astronauts on board Atlantis, three on Soyuz and three on ISS), it was the most people in space at the same time since April 2001, when the ISS-2, STS-100 and Soyuz TM32 crews (totalling 13 crew members) were all aloft. The hatches were open for 5 days 21 hours and 57 minutes and during this time, the two crews transferred 362.88 kg of hardware and 473 kg of water into the station and returned 491 kg of unwanted hardware and trash. In addition, 90.72 kg of launch lock restraints and unnecessary hardware was placed in Progress M56 for disposal.

Another inspection of the TPS of Atlantis was completed the day after undocking and the following day, the Shuttle crew spoke with both the crew on ISS and the crew on the approaching Soyuz TMA9 craft in a three-way link up. On 19 September the mission was extended in order to re-check some of the TPS areas of Atlantis after small unidentified particles were found floating near the Shuttle. There were sufficient supplies to allow the mission to be extended until 22 September or for them to return to ISS for a possible rescue mission if anything untoward been found. However, analysis revealed no significant problems and Atlantis was cleared for landing on 21 September (the previous day had been ruled out due to weather concerns). In the event all went well, and Atlantis made a textbook landing at night at the SLF at the Cape.

During homecoming events in Houston on 21 September, Stefanyshyn-Piper collapsed twice and had to be assisted by officials and crew members. She was not taken to hospital and the effects were attributed to her adjustment to gravity after her first 12-day flight into space.

Milestones

249th manned space flight

146th US manned space flight

116th Shuttle mission

27th flight of Atlantis

19th Shuttle ISS mission

7th Atlantis ISS mission

59th US and 98th flight with EVA operations

1963-015A

1963-015A