|

|

Int. Designation

|

1983-116A

|

|

Launched

|

28 November 1983

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

8 December 1983

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-102 Columbia/ET-11/SRB A55; A60/SSME #1 2011; #2 2018; #3 2019

|

|

Duration

|

10 days 7 hrs 47 min 23 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Columbia

|

|

Objective

|

First flight of European-built Spacelab pressurised scientific laboratory (Spacelab 1)

|

Flight Crew

YOUNG, John Watts Jr., 53, USN, commander, 6th mission Previous missions: Gemini 3 (1965); Gemini 10 (1966); Apollo 10 (1969); Apollo 16 (1972), STS-1 (1981)

SHAW, Brewster Hopkinson Jr., 38, USAF, pilot

GARRIOTT, Owen Kay, 53, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Skylab 3 (1973)

PARKER, Robert Allan Ridley, 46, civilian, mission specialist 2 MERBOLD, Ulf, 42, civilian, payload specialist 1 LICHTENBERG, Byron Kurt, 35, civilian, payload specialist 2

Flight Log

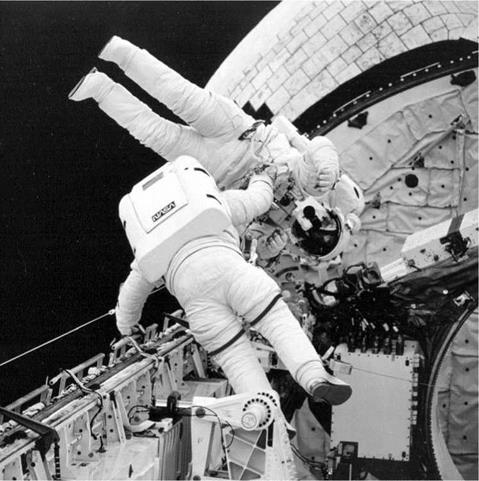

This mission, originally scheduled for 30 September, was delayed for a month to allow time for Columbia’s SRB nozzles to be replaced following the STS-8 launch scare. The Shuttle rose from Pad 39A at 16: 00 hrs local time at the Kennedy Space Center, carrying a unique crew of six, including the apparently ageless veteran of space flight, John Young, in the commander’s seat. Columbia performed a startling 140° roll programme to place it on an azimuth heading for a 57° inclination orbit – the highest achieved on a US manned space flight. As a result, the Shuttle could be seen passing over Britain just after entering its orbit, which would have a maximum altitude of 216 km (134 miles).

On the schedule was a nine-day intensively scientific mission aboard the first Spacelab payload bay-mounted laboratory. This was built by the European Space Agency as a result of an agreement signed with NASA ten years earlier, at a cost of $850 million. The nine-day mission, which featured the first time that the principal investigators could talk directly to experiments in space via the TDRS-1 relay satellite, was judged a phenomenal success. Altogether, 73 separate investigations were

|

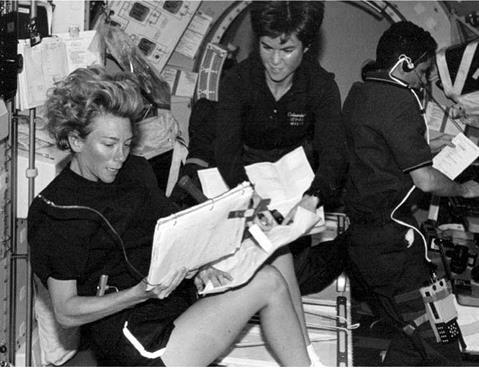

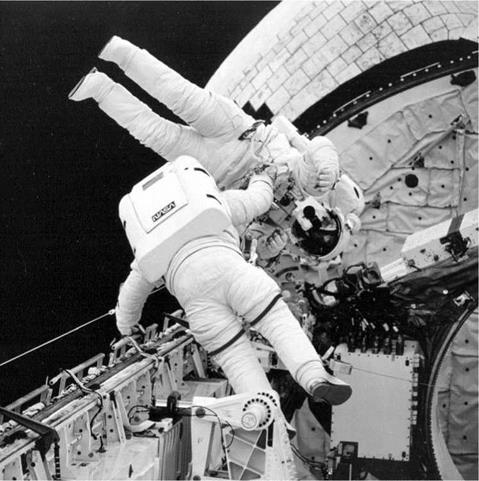

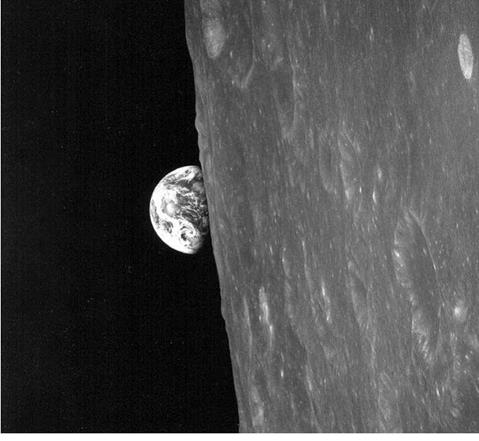

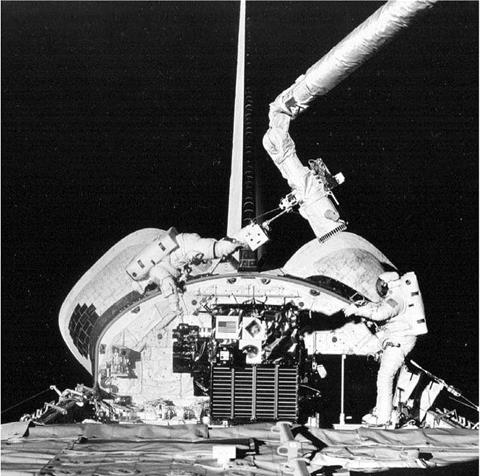

The Spacelab 1 Module in Columbia’s payload bay. In the foreground is the access tunnel from the Shuttle mid-deck

|

completed in the fields of astronomy, physics, atmospheric physics, Earth observations, life sciences, material sciences, space plasma physics and technology. The crew split into two shifts which lasted twelve hours, sometimes more like eighteen hours, so much so that mission controllers extended the mission. The Red Shift comprised Young, Parker and Merbold (representing ESA), while the Blue Shift included Shaw, Garriott and Lichtenberg (representing the American science community).

Strapped in their seats and ready to come home, the crew got an unplanned nine hour flight extension when a major computer failure stopped the OMS retro-burn just before it started. Computer 1 failed, then computer 2, which had taken over operations instantly, also shut down. Young and his pilot Brewster Shaw sweated over troubleshooting the problem, and with everything crossed, fired the OMS engines for another try. The computer fault had been due to contaminated integrated circuits. All went well and Columbia homed in on Edwards Air Force Base’s dry lake bed runway 17, landing at T + 10 days 7 hours 47 minutes 23 seconds, the longest six-crew

mission. Two minutes later, the troubled Columbia caused another scare by catching fire, leaking hydrazine from an APU being the cause. As the pilot and commander winged their way to Houston, the four other crewmen took part in intensive life sciences investigations, which included another dose of zero-G in a KC-135 aircraft.

Milestones

94th manned space flight

40th US manned space flight

9th Shuttle mission

6th flight of Columbia

1st Spacelab Long Module mission

1st flight with six crew members

1st flight to carry a West German

1st flight with crew member on sixth mission

1st US flight with non-American crew member

1st flight with payload specialist crew members

|

Int. Designation

|

1986-003A

|

|

Launched

|

12 January 1986

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

18 January 1986

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 22, Edwards Air Force Base, California

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-102 Columbia/ET-30/SRB BI-024/SSME #1 2015;

|

|

#2 2018; #3 2109

|

|

Duration

|

6 days 2 hrs 3 min 51 sec

|

|

Callsign

|

Columbia

|

|

Objective

|

Satellite deployment mission

|

Flight Crew

GIBSON, Robert Lee “Hoot”, 39, USN, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-B (1984)

BOLDEN, Charles Frank Jr., 39, USMC, pilot

NELSON, George Driver, 35, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-C (1984)

HAWLEY, Steven Alan, 34, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-D (1984)

CHANG-DIAZ, Franklin Ramon, 35, civilian, mission specialist 3 CENKER, Robert J., 37, civilian, payload specialist 1 NELSON, C. William, 43, US Congressman, payload specialist 2

Flight Log

This mission was dubbed “Mission Impossible” by the press and thoroughly earned its nickname, making eight attempts to launch, five of them when the crew was aboard. Columbia, making its first space flight since STS-9 in 1983 and after a planned period of modification, was on the pad on 18 December 1985 for its first attempt, which was routinely postponed for a day because of the longer time it was taking to close out the aft compartment of the orbiter. The launch reached T — 14 seconds on 19 December, when a back-up hydraulic unit on one of the SRBs failed to activate on time.

With Christmas coming up and with the orbiter Challenger already poised for a lift-off on sister pad 39B, NASA felt comfortable about delaying “Mission Impossible” until 6 January. That launch was scrubbed at T — 31 seconds after 6,350 kg (14,000 lb) of liquid oxygen had been accidentally drained from the external tank by a careless but overworked controller. The following day, the crew climbed aboard resigned to another launch scrub, at T — 9 minutes, such were the appalling weather conditions. Before the crew had got aboard, all seemed to augur well for

|

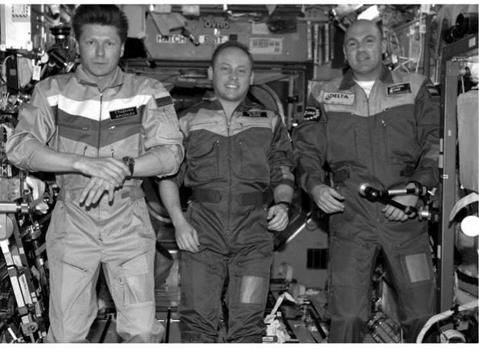

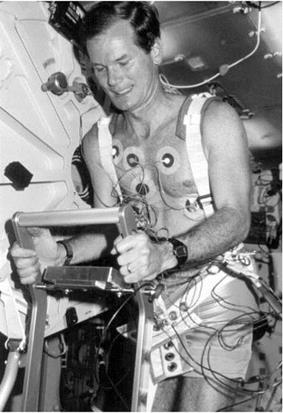

Payload specialist and US Congressman Bill Nelson exercises on the treadmill in the mid-deck of Columbia

|

9 January, but the countdown again reached T — 9 minutes only for a sensor to break on the launch pad and stop the count. After another delay due to bad weather and with the crew on board for the fifth time (and, thanks to his 41-D experience, with Steven Hawley on board a Shuttle poised for lift-off for a record eighth time), Columbia at last made a dramatic dawn exit from the Kennedy Space Center on 12 January, leaving a dark contrail in the dark blue sky with a pinpoint of light at its end as it headed for space. A hydraulic failure on one of the SSMEs just after lift-off momentarily raised fears of an RTLS abort.

With commander Hoot Gibson and his crew of two veterans and four rookies, including Congressman Bill Nelson (who served on a Senate committee which controlled NASA’s purse strings) flying as a political observer, Columbia set to work. This did not seem too hard, since only one satellite, Satcom Ku 1, needed to be deployed. A special camera designed to photograph Halley’s Comet failed, much to the chagrin of astronomer George Nelson (no relation to Bill, on the first flight to include crew members with the same surname). Another passenger was the second industrial payload specialist, RCA’s Robert Cenker. NASA planned to fly several more from other companies, and even a citizen’s representative, a US teacher, during 1986.

The “Mission Impossible” tag stuck until the end of the mission too, since NASA, wanting Columbia home at the Kennedy Space Center for the first landing there since 51-D for a turnaround of the 61-E Shuttle mission to observe Halley’s Comet, delayed the landing twice, by which time the weather was so bad that it was diverted to Edwards. Columbia landed at T + 6 days 2 hours 3 minutes 51 seconds – the shortest seven-crew flight – adding days to the turnaround time. Maximum altitude achieved in the 28° inclination orbit was 296 km (184 miles).

Milestones

114th manned space flight 55th US manned space flight 24th Shuttle flight 7th flight of Columbia

1st manned space flight carrying two crew with same surname

Flight Crew

SCOBEE, Francis Richard “Dick”, 47, USAF, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-C (1984)

SMITH, Michael John, 40, USN, pilot

ONIZUKA, Ellison Shoji, 39, USAF, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 51-C (1985)

RESNIK, Judith Arlene, 40, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-D (1984)

McNAIR, Ronald Erwin, 35, civilian, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 41-B (1984)

JARVIS, Gregory Bruce, 41, civilian, payload specialist 1 McAULIFFE, Sharon Christa Corrigan, 37, civilian, payload specialist 2

Flight Log

The apparently routine nature of Space Shuttle missions and the transportation of industrial payload specialists, foreign passengers and political observers resulted in an inevitable call for a US citizen to fly. At first, a journalist-in-space programme was suggested, but President Reagan decided that the first citizen in space would be a teacher. A nationwide competition resulted in the choice of Christa McAuliffe, while at the same time, a journalist-in-space nationwide competition reached a stage where 100 had been short-listed for a flight to take place later in 1986.

McAuliffe was assigned to Challenger mission STS 51-L, along with an industrial payload specialist from Hughes, Gregory Jarvis, whose bad luck it had been to have already been assigned to and bumped off three missions in 1985. STS 51-L was delayed from December 1985 to 22 January 1986 and was routinely delayed further due to operational difficulties on 23 and 24 January. By 25 January, the launch window was to have been pushed into the morning, requiring reprogramming of computers, so

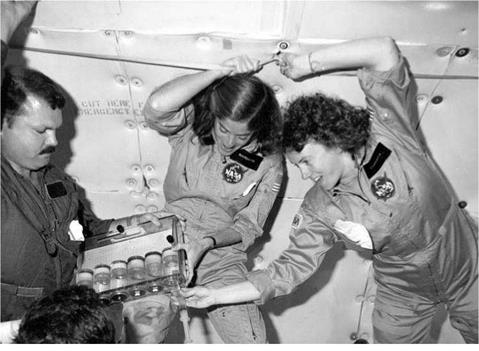

|

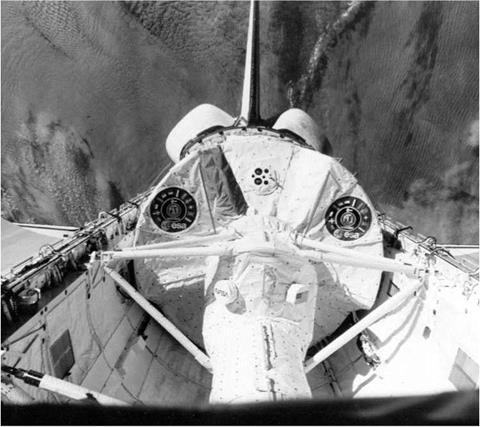

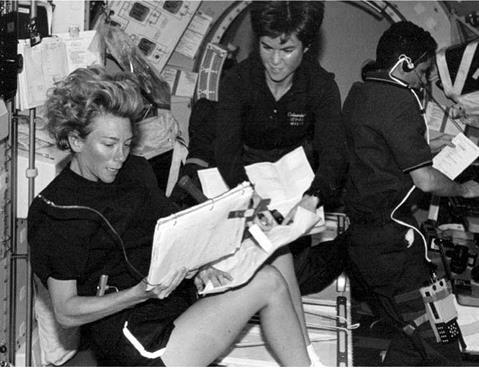

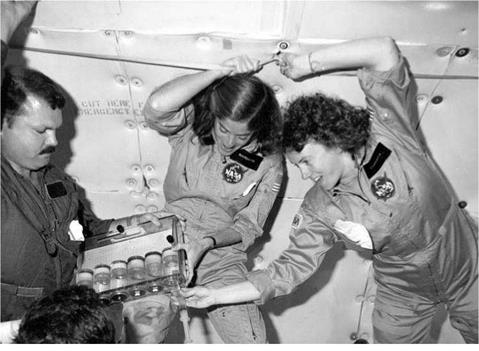

Teachers in Space candidates Barbara Morgan (centre) and Christa McAuliffe (right) practice working on experiments for STS 51-L aboard NASA’s zero-G aircraft

|

another delay ensued. The following day, 26 January, seemed acceptable, but officials decided to cancel the attempt because of predicted bad weather, which actually turned out to be fine. Vice President George Bush had expressed an interest in seeing the Challenger launch but would not have been able to get to the Kennedy Space Center until 27 January (which was also the 19th anniversary of the Apollo 1 fire), he told NASA. In the end, he did not come for the new launch attempt on that date, which was cancelled when the handle of the orbiter hatch would not close properly. When that problem had been fixed, crosswinds at the KSC runway in the event of an RTLS abort were unacceptable.

The crew exited, prepared for an attempt the following day, and were aboard Challenger again at 08: 36 hrs on a bright but very cold day, with ice having been reported on the launch pad. Liquid hydrogen tanking delays caused by hardware interface problems further delayed the launch two hours, until 11 : 38 hrs. As the SSMEs built up to full thrust as usual, the Shuttle “stack” thrusted forward laterally, only to be “twanged” back at SRB ignition. This manoeuvre places an excessive load on the lower attach rings of each booster where they are linked to the external tank. In the case of 51-L, the excessive loads caused a small rupture in the casing of the right – hand SRB, which immediately caused a sideways spurt of flame that could not be spotted within the intense brilliance of the main SRB exhaust at lift-off.

Mission specialist Judy Resnik immediately noticed that the temperature of the liquid hydrogen being fed from the external tank to the SSMEs was high. Commander Dick Scobee tried to look sideways and backwards out of his window to see if he could spot the reason why. As Challenger completed its roll programme, it was obvious to the crew and observers north and south of the pad that the Shuttle was “fishtailing”. Loss of thrust in the right-hand SRB was being compensated for by the thrust vector control in the left-hand booster. Challenger continued its rocky and wild ride upwards, startling the pilot Mike Smith. Scobee and Smith realised that there was a serious problem and called up the pressure reading on the right-hand SRB. Meanwhile, the rupture in the SRB casing, which was shedding debris throughout the launch and causing an extremely messy contrail, in stark contrast to previous launches, caused the double О-rings to fail in one of the joints of the SRB and flame was later seen emanating from it.

When Scobee and Smith saw the pressure reading on the SRB they must have known that they were in trouble. Meanwhile, Houston had given Challenger the “go at throttle up” call, indicating that all was well, and no doubt a somewhat puzzled Scobee gave the last public utterance from the doomed ship, acknowledging the call. Leaking hydrogen from the now-breached external tank was igniting and a glow could be seen in the TV shots of Challenger, which did not show what was about to happen in a matter of milliseconds on its other side. At T + 73 seconds, pilot Smith uttered the final recorded words, “Uh-oh,” as the right-hand booster broke from its mooring, broke through the wing of Challenger as the upper attachment broke, and ruptured the external tank.

Flying at Mach 1.92 at an altitude of 14,020 m (45,997 ft), Challenger was enveloped in the explosion, and broke apart under severe aerodynamic loads. The cabin section of Challenger emerged intact from the cataclysm, imposing a tolerably brief period of 20-G forces on the crew, as the two SRBs continued their flight independently before being blown up some seconds later. The cabin may have depressurised, rendering the astronauts unconscious in seconds, but there is evidence to suggest that it did not happen immediately, as at some stage, Resnik activated both Scobee and Smith’s emergency compressed air packs. These would not have been much use at high altitude. The crew was alive but not necessarily conscious as the cabin began a two-and-a-half minute plunge into the Atlantic Ocean, breaking up on impact and instantly killing all seven crew members, Scobee, Smith, Resnik and Ellison Onizuka in the flight deck and Ronald McNair, Jarvis and McAuliffe in the mid-deck. Along with several pieces of debris, the shattered crew cabin and parts of the remains of the crew were recovered later, along with the crew cockpit recorder, which revealed the conversation during the launch.

NASA said that the crew was totally unaware that anything was wrong, a conclusion reached by the Rogers commission which investigated the accident and, despite a mountain of evidence, decided that the only cause of the accident was failed О-rings, damaged by the low temperatures before launch. Analyses of the accident by several engineers were refuted by NASA, though many suggestions were later incorporated quietly into the programme, including strengthening the attach ring system and testing it thoroughly during the Shuttle recovery programme. Partly in respect to the crew, STS 51-L is categorised by NASA as a “space mission in progress” when it failed and is counted as a “mission” for the crew with a 1 minute 13 second “duration”, the point when contact was lost with the crew, even though it did not reach the official recognised altitude to be called a true “space flight”.

Several important redesigns were made to the whole system, including the O-rings and seals between the segments of the SRBs, the official cause of the disaster. The spectre of “Challenger” continued to haunt NASA and was brought back to the headlines in February 2003 when a second Shuttle and crew were lost, leading to the decision to finally retire the Shuttle when its obligation to the International Space Station programme had been completed.

Milestones

25th Shuttle mission

10th and final flight of Challenger

2nd (intended) TDRS deployment mission

1st attempted manned space flight to launch and not reach space 1st loss of manned space vehicle during launch 1st US in-flight fatalities in space programme

Flight Crew

KIZIM, Leonid Denisovich, 44, Soviet Air Force, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: Soyuz T3 (1982); Soyuz T10 (1984)

SOLOVYOV, Vladimir Alekseyevich, 39, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz T10 (1984)

Flight Log

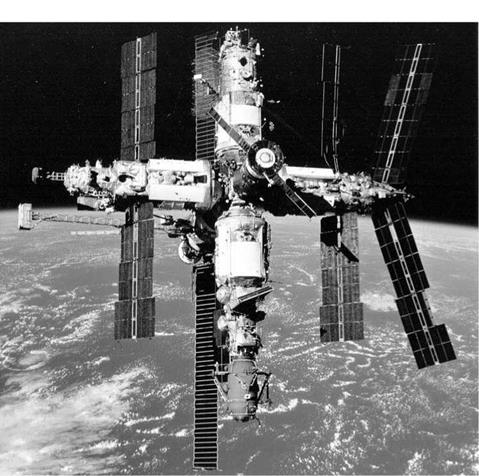

As a result of the evacuation of Salyut 7 by the T14 crew, some of the experiment results had not been returned and some of the research programmes not completed. The sole remaining Soyuz T vehicle was ready to fly to the station (using the refurbished DM from the September 1983 T10-1 pad abort), and as the replacement Soyuz TM was not yet ready, this was the only vehicle available to the Soviets to continue their presence in space during 1986. In addition, the next space station was ready for launch, but its planned add-on modules were not. Therefore, it was decided to send the T15 crew to the core module of the new station first, then revisit Salyut 7 to complete the work there, and finally return to the new station to complete their programme in preparation for fully operational activities from 1987. On 20 February 1986,22 days after the American manned space programme’s tragic Space Shuttle loss and the beginning of what was to be a lengthy period on the ground, the Soviets launched the new space station, called Mir (Peace) and not Salyut 8 as many Western observers had expected. The ballyhoo surrounding the launch seemed to indicate that this was the expected giant station, launched aboard the first heavy lift Saturn V-type booster. In fact, it soon became obvious that Mir (1986-017A/DOS-7) was merely a beefed up Salyut, with one major difference: a docking pod at the front which would take five separate spacecraft. With the rear docking port, a sixth could be added, making it possible to erect the first modular space station.

Mir was to be fully operational by 1990, said the Soviets, with four large add-on modules mounted radially on the front pod. Mir weighed 20.9 tonnes and measured

|

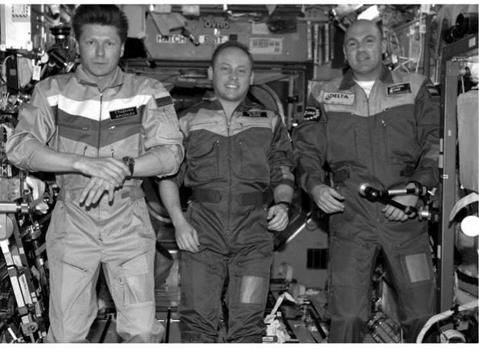

Solovyov (left) and Kizim (entering the rear door of an Orlan suit) during EVA training for their historic dual space station mission

|

13.13 m (43 ft), with a maximum diameter of 4.15 m (13.5 ft), and comprised a transfer compartment and two work compartments, with a service propulsion system at the rear. It had two solar panels with a total span of 29.73 m (97.5 ft). The first crew to visit in space were Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov, who were trained for a mission to Salyut. They were the first all-Soviet crew to fly an exclusively Soviet mission that was named before lift-off, the time of which was also given and seen live on TV, another first for an all-Soviet crew mission. Launch was at 18: 33 hrs local time from Baikonur on 13 March, with docking occurring two days later.

Their basic job was to ready Mir for occupation by Mir-trained crews, when addon modules had been attached. The crew also became the first to use a relay satellite, Cosmos 1700, to conduct real-time conversations with mission control at Kaliningrad. Two Progress tankers, Nos. 25 and 26, arrived in April and May to stock up the station, which the crew then surprisingly left on 5 May. But this was not to return home. Instead, they made a unique rendezvous and docking with Salyut 7. While the cosmonauts were aboard Salyut 7, an unmanned version of the new Soyuz TM spacecraft docked to Mir on 23 May, while Progress 26 was still attached. It returned home on 29 May.

During their stay aboard Salyut 7, the cosmonauts completed much of the work that had been intended for the Soyuz T14 crew, including two EVAs to erect a structure in space 50 m (164 ft) long that resembled the Shuttle 61-B EASE-ACCESS exercises. The walk on 28 May lasted 3 hours 50 minutes and the one on 31 May, 4 hours 40 minutes, making them the first spacemen to make seven and eight EVAs. Kizim and Solovyov ended their second stay aboard Salyut 7 on 25 June when they undocked and, again surprising some observers, returned to Mir rather than coming home, clocking up yet another first in a flight with so many such facts and feats for the statistician to record.

Salyut 7-Cosmos 1686 was placed into a 475 km (295 miles) storage orbit. Salyut 7 remained in space, unoccupied, for the next five years, finally re-entering in February 1991. The cosmonauts, with their spacecraft crammed with as much equipment from Salyut as possible, docked with Mir on 26 June. Work continued aboard Mir before it was announced – again another first – that they were returning home on 16 July and would be covered live on TV. Touchdown came at T + 125 days 0 hours 1 minute. During the mission, Kizim had become the first person to clock up a year’s space experience, bringing his personal total at the end of the mission to 374 days. Maximum altitude achieved during the 51° mission was 349 km (217 miles).

Milestones

115th manned space flight

60th Soviet manned space flight

53rd Soyuz manned space flight

14th Soyuz T manned space flight

14th and last Soyuz T mission

1st flight by crew making seventh and eighth EVAs

1st manned docking with two separate vehicles

1st manned visit to two space stations

1st manned re-visit to space station

1st crewman to amass one year of space experience

1st Soviet use of a data relay satellite on manned space flight

11th Soviet and 34th flight with EVA operations

Flight Crew

ROMANENKO, Yuri Viktorovich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz 26 (1977); Soyuz 38 (1980)

LAVEIKIN, Aleksandr Ivanovich, 36, civilian, flight engineer

Flight Log

The first crew to be fully operational aboard Mir was due to be Vladimir Titov and Aleksandr Serebrov, but their places aboard Soyuz TM2 were taken by the veteran Yuri Romanenko and rookie Aleksandr Laveikin, apparently days before the launch and possibly due to illness. The spectacular night launch was shown live on TV from Baikonur, at 01: 38 hrs local time. The new spacecraft, Soyuz TM2 (Soyuz TM, the first of the series, was an unmanned test flight that docked to Mir in May 1986) took two days to reach Mir. The crew docked safely at the front and their first job was to unload Progress 27 from the rear port, which had docked on 18 January in preparation for their mission.

Laveikin became one of the few space explorers whose adaptation to weightlessness is “painful”, as it was described by officials. Another Progress, No.28, arrived on 5 March, armed to the hilt with an array of scientific instruments to make the crew as busy and productive as possible. The equipment included the Korund crystal growth machine which was ultimately used to make useful electronic crystals, and the KATE 140 remote-sensing camera. Another device already aboard Mir, called Pion M, was used for extensive materials processing experiments.

The first add-on module was expected to be launched, and to prepare for it, Progress 28 undocked. Kvant, a module armed with an array of astrophysics experiments and with an externally mounted electrophoresis device attached, was launched by a Proton on 1 April, at 05 : 06 hrs local time. It weighed as much as Mir but after its planned docking it was to shed its propulsion module and would weigh 11 tonnes. Its

|

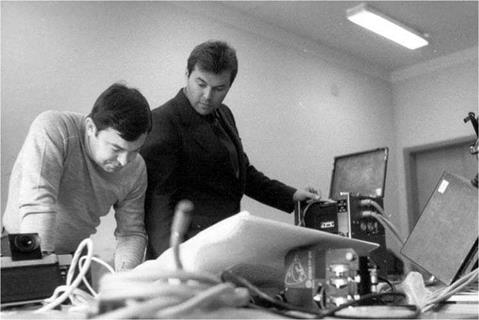

Romanenko and Laveikin review training plans for their residency on the Mir station

|

docking was a dramatic affair to say the least. On 5 April, Kvant failed to brake at a distance of200 m (656 ft) and, according to Romanenko, sped dangerously by Mir at a distance of just 30 m (98 ft). Another docking attempt was made on 9 April, with Mir aiding the manoeuvres, but Kvant’s probe got stuck and a hard-dock was not achieved. Something was blocking the docking port.

What that something was would be discovered during an unscheduled EVA by Romanenko and Laveikin on 11 April, during which they had to crawl through a tightly fitting hatch at the front of Mir and then scramble over the station to get to the rear. The cosmonauts saw that a white sheet of plastic was blocking the port, having been left there by Progress 28 which had inadvertently been launched with it attached after a technician failed to remove it. It was removed from the docking port and the hard docking was completed. The cosmonauts ended a highly successful 3 hour 40 minute EVA. They later entered Kvant to place it in operational status while its propulsion module was jettisoned – but not de-orbited due to lack of fuel – to expose a docking port for new Progress tankers, the next of which arrived on 21 April.

Progress 29, the third craft attached to the Mir core, was primarily used to load propellant into Mir’s propulsion system, ingeniously through lines in Kvant. Another Progress was to arrive on 21 May, while Kvant was being used to make the first of its extremely useful observations of the Universe using telescopes, one of which was provided by the UK. A second EVA, lasting 1 hour 53 minutes, was made on 12 June, to begin the erection outside Mir of a two-part array of solar panels, 10 m (33 ft) high, which would increase Mir’s electrical power. The second EVA, on June 16, lasted 3 hours 5 minutes.

The first international and visiting mission to Mir, Soyuz TM3, docked on 24 July, carrying a rookie commander, a Syrian pilot and a veteran, Aleksandr Aleksandrov, who was told a month before his scheduled eight-day trip that he was to replace Laveikin, whose heart was giving doctors cause for concern. Soyuz TM2 returned with Laveikin, having clocked up 174 days, leaving Aleksandrov with Romanenko, who exceeded the Soyuz T10 endurance record on 30 September. During their residency, Progress 31 (5 August) and 32 (26 September) were used to replenish the station with fuel, propellant and supplies, while on 31 August the crew were ordered to don their suits and get into the fresh TM3 for an emergency return to Earth. This exercise was not completed since it was, unbeknown to the crew at that time, a safety test.

During another unique test on 10 November, Progress 32 was undocked and redocked to the rear of Kvant, perhaps to prepare for the introduction in later Mir operations of free-flying materials processing labs, conducting experiments autonomously of the type that Romanenko and Aleksandrov were in Mir. Yet another Progress, No. 33, replaced No. 32 on 23 November, with more esoteric processing equipment to test. Maximum altitude achieved during the 51° mission was 370 km (230 miles). On 23 December, Soyuz TM4 arrived, with the next long duration duo, Vladimir Titov and rookie Musa Manarov, as well as a Shuttle test pilot whom Romanenko had never met, called Anatoly Levchenko.

TM3 returned to Earth, with Romanenko, Aleksandrov and Levchenko all having clocked up different flight times and all of whom had been launched separately in the first landing of its kind in space history. Romanenko’s condition after the 326 day 11 hour 37 minute mission originally launched in TM2 was remarkably good, although for precautionary reasons he was stretchered from the spacecraft. Ridiculous rumours persisted in some popular western newspapers that he was a “wreck’’.

Milestones

116th manned space flight

61st Soviet manned space flight

54th Soyuz manned space flight

1st Soyuz TM manned space flight

1st manned space flight over 300 days

1st landing with three crewmen launched separately

1st flight with crew members meeting for the first time

12th Soviet and 35th flight with EVA operations

Romanenko sets new space endurance record 326 days 11 hours

Laveikin celebrates his 36th birthday in space (21 Apr)

Romanenko celebrates his 43rd birthday in space (1 Aug)

Flight Crew

VIKTORENKO, Aleksandr Stepanovich, 40, Soviet Air Force, commander ALEKSANDROV, Aleksandr Pavlovich, 44, civilian, flight engineer,

2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz T9 (1983)

FARIS, Mohammed, 36, Syrian Air Force, cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

Accompanied by the now customary live television coverage, Soyuz TM3 blasted of from Baikonur at 07: 59 hrs local time into clear blue skies en route for the Mir space station, carrying the first visiting crew to see the new complex in which Yuri Romanenko and Aleksandr Laveikin had been residing since the previous February. TM3 carried a cosmonaut from Syria, the nineteenth nation to have a man in space, plus commander Aleksandr Viktorenko and flight engineer Aleksandr Aleksandrov. The latter was told a month before lift-off that he was to remain aboard Mir until the end of the year, replacing Laveikin whose electrocardiograph readings were causing some concern.

Two days later, TM3 docked at the rear of Mir at the Kvant port, and soon five people were floating around inside. The Syrian, Mohammed Faris, had the usual complement of national experiments to conduct, including electrophoresis, crystal growth, remote sensing – during rare passes over Syria – and an ionospheric monitoring programme. The first international mission to return with a replacement crewman, Faris and Viktorenko entered the old TM2 with Laveikin and landed at T + 7 days 23 hours 4 minutes 5 seconds, 140 km (87 miles) northeast of Arkalyk, just 2 km (1 mile) from some settlement buildings, much to the relief of observers.

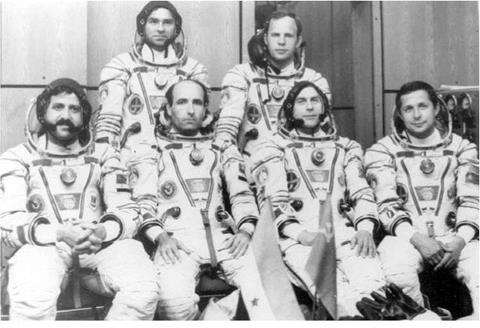

|

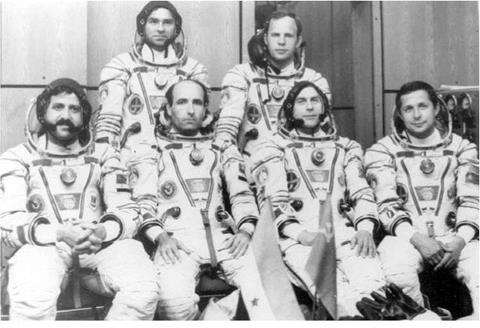

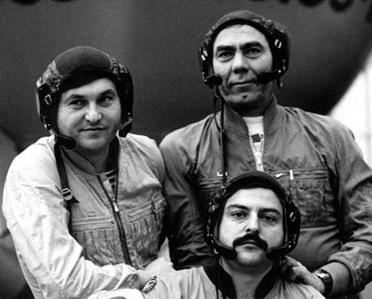

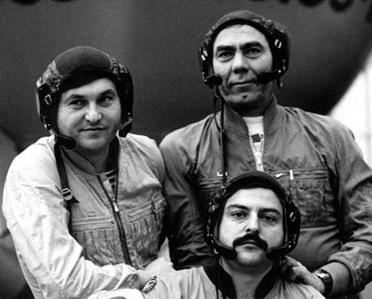

The prime and back-up crews of Soyuz TM3. At rear (1 to r) Viktorenko and A. Solovyov. At front (1 to r) Faris, Habib, Aleksandrov and Savinykh

|

Laveikin seemed pale but cheerful after his 174-day flight and doctors later declared him fit for another flight, while Syria celebrated. Maximum altitude during the 51° mission was 359 km (223 miles).

Milestones

117th manned space flight 62nd Soviet manned space flight 55th Soyuz manned space flight 2nd Soyuz TM manned space flight 3rd Soyuz international mission 1st flight by a Syrian

Flight Crew

TITOV, Vladimir Georgyevich, 41, Soviet Air Force, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: Soyuz T8 (1983); Soyuz T10-1 (1983)

MANAROV, Musa Khriramovich, 36, civilian, flight engineer LEVCHENKO, Anatoly Semenovich, 46, civilian, cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

In September 1985, the initial Mir resident crews were formed. The first crew would be Vladimir Titov and Alexander Serebrov; the second, Romanenko and Manarov; and the third, Alexander Volkov and Sergei Yemelyonov. When the Soyuz T15 crew were launched to Mir, the training of these crews was extended, and delays in the construction of modules also delayed their missions into 1987/1988. Then Manarov became ill and was replaced by Laveikin. Serebrov also fell ill and so Crew 2 replaced Crew 1 for the Soyuz TM2 mission flown in 1987. Manarov was restored to flight status and replaced Serebrov, joining Titov to form a new Crew 3. Yemelyanov was also removed from flight status during 1987 for medical reasons and was replaced first by Alexander Kaleri, then Sergei Krikalev, who was paired with Volkov as crew 4.

The Soyuz TM4/EO-3 crew would remain in space for a year, and would be joined for the ascent to Mir by one of the Buran shuttle pilots, who would return with the EO-2 crew after about a week in space. Like Igor Volk, a crewman on Soyuz T12 in 1984, another of this band of future shuttle pilots, Anatoly Levchenko, was to be given eight days space experience, at the end of which he would immediately get aboard a shuttle training aircraft to make simulated landings, to ensure that weightlessness did not impair his faculties. The first flight of the Soviet shuttle was clearly quite close, observers thought.

The new TM4 trio were launched from Baikonur at 17: 18 hrs local time on 21 December and within two days were aboard Mir, with Romanenko and

|

The Soyuz TM4 crew of Titov, Levchenko (standing) and Manarov (front)

|

Aleksandrov, who were meeting Levchenko for the first time. Five days later, Romanenko, Aleksandrov and Levchenko were landing aboard Soyuz TM3, a unique crew indeed, having each been launched separately and each having clocked up different flight times. With the changeover complete, Titov and the rookie flight engineer Manarov began their long, historic, but quietly received mission by placing Soyuz TM4 at the front of Mir to prepare for the arrival of their first Progress support ship, No.34. This duly arrived on 23 January 1988 with two tonnes of scientific and other equipment. Progress also transferred propellant into Mir’s depleting tanks.

Titov and Manarov took 4 hours 25 minutes exercise outside Mir on 26 February, when they replaced a faulty part of the new solar panel that had been erected by Romanenko and Laveikin. Progress 34 was replaced by No.35 on 25 March and then No.36 on 15 May, as the mission proceeded routinely, unheralded and unwatched by most of the world.

The cosmonauts were due to make an EVA in late May to repair faulty instruments on the Kvant astrophysics laboratory, but their work was delayed until after the departure of a new visiting crew aboard Soyuz TM5. Bulgaria’s second cosmonaut (confusingly also called Aleksandr Aleksandrov) arrived with commander Anatoly Solovyov and flight engineer Viktor Savinykh on 9 June and remained for eight days, rather than the usual six for a Mir visiting mission. When they had left, Titov and Manarov moved the fresh TM5 craft to the front of Mir, making room for another Progress, and prepared for their next spacewalk which they made on 30 June.

During the 5 hour EVA, the cosmonauts struggled to replace a detector unit on Kvant because of a faulty tool, and had to be recalled while new tools were prepared

and launched on the next Progress, No.37, which arrived on 20 July. The EVA, however, was delayed until after the departure of the next visiting crew aboard Soyuz TM6, which replaced Progress 37. This arrived at Mir on 31 August, carrying Vladimir Lyakhov, an Afghan cosmonaut researcher and, getting a taste of space at last, Doctor Valery Polyakov, who was to stay with Titov and Manarov throughout the remainder of their stay to monitor the medical condition of the core crew as they approached the end of their long pioneering mission, and then remain himself with the next resident crew. Lyakhov and the Afghan, Abdul Mohmand, left in Soyuz TM5 on 5 September, straight into a one-day drama which could have ended with them being stranded in orbit. Progress 38 duly arrived at Mir on 12 September.

On 20 October, the cosmonauts made their much-delayed EVA, after as much preparation and discussion from the ground as possible. The 4 hour 20 minute effort was a success, with Kvant’s TTM telescope fully operational again. Titov and Manarov broke Romanenko’s duration record on 11 November. By this time it had been announced that French cosmonaut Jean-Loup Chretien would be launched on 21 November with two Soviets, on a longer than usual visiting mission, returning with Titov and Manarov on their 365th day in space. This launch of Soyuz TM7 was delayed to 26 November and reached Mir two days later.

With Chretien were Aleksandr Volkov, with whom he made an EVA, and flight engineer Sergei Krikalev. He and Volkov were to be Polyakov’s new companions until the following April, said the Soviets. The comings and goings from Mir were by now getting rather complicated to follow.

The long awaited return of the new space record holders, Titov and Manarov, with Chretien, took place aboard Soyuz TM6 on 21 December after a one-orbit delay before retro-fire because of a computer software problem. The Orbital Module remained with the craft until after retro-fire to avoid problems that were experienced with TM5. The crew flew straight to Star City rather than to Baikonur because of an outbreak of hepatitis at the launch facility. Both cosmonauts recovered well after their 365 day 22 hour 39 minute mission, the longest manned space flight to that point. Chretien clocked up 25 days. The Soviets then announced that, for the time being, long duration flights would be restricted to about five months.

Milestones

118th manned space flight 63rd Soviet manned space flight 56th Soyuz manned space flight 3rd Soyuz TM manned space flight 1st manned space flight to last one year

Titov and Manarov set new endurance record of 365 days 22 hours 13th Soviet and 36th flight with EVA operations Titov celebrates his 41st birthday in space (1 Jan)

Manarov celebrates his 37th birthday in space (22 Mar)

Flight Crew

SOLOVYOV, Anatoly Yakovlovich, 40, Soviet Air Force, commander SAVINYKH, Viktor Petrovich, 48, civilian, flight engineer, 3rd mission Previous missions: Soyuz T4 (1981); Soyuz T13 (1985)

ALEKSANDROV, Aleksandr Panayatov, 37, Bulgarian Air Force, cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

Bulgaria’s first cosmonaut, Georgy Ivanov, became the only international space traveller not to reach a Soviet space station when Soyuz 33 malfunctioned in 1979. To make amends, the Soviets offered Bulgaria another try, even flying Ivanov’s back-up, Aleksandr Aleksandrov. This caused confusion among the non-specialist press covering the mission because the other, Soviet, Aleksandr Aleksandrov had recently returned from Mir himself. The Soviets also provided a flight of ten days to make up for the five days that Ivanov lost when he had to come home early.

The Bulgarian flight was well prepared and packed with 40 science experiments, many of which were left on Mir for further use. Of all the international missions thus far, this seemed to be the most fruitful nationally. Launch in Soyuz TM5, with rookie commander Anatoly Solovyov and veteran flight engineer Viktor Savinykh, came at 20:03 hrs local time, and the docking followed smoothly on 9 June. Aleksandrov’s array of experiments included eight for Earth remote sensing and manufacturing units to produce composite alloys in weightlessness. The mission ended inside Soyuz TM4 at T + 9 days 20 hours 10 minutes in a lake bed – fortunately bone dry – in 42° temperatures.

Milestones

119th manned space flight 64th Soviet manned space flight

57th Soyuz manned space flight 4th Soyuz TM manned space flight 4th Soyuz international space flight

1st Soviet flight carrying second foreign crewman from the same country (Bulgaria)

Flight Crew

LYAKHOV, Vladimir Afanasyevich, 47, Soviet Air Force, commander, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz 32 (1979); Soyuz T9 (1983)

POLYAKOV, Valery, 46, civilian, flight engineer

MOHMAND, Abdul Ahad, 29, Afghan Air Force, cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

Soyuz TM6 was launched routinely from Baikonur at 07: 23 hrs local time, watched live on television. Inside the spacecraft were commander Vladimir Lyakhov, Doctor Valery Polyakov and Afghan pilot, Abdul Mohmand who, considering the Soviet – Afghan war at the time, featured in the most incongruous and unabashed political Soviet international mission, the last “free” ride for a foreigner. After Mohmand’s statutory six-day stay aboard Mir, he left the space station aboard TM5, with his commander, leaving Polyakov to ride out Titov and Manarov’s marathon stay.

The Orbital Module was jettisoned and TM5’s computer began the retro-fire sequence. The prime infra horizon sensors attempted to orientate the spacecraft correctly, but because the Sun had just set, became confused. The retro-engine was primed and ready to ignite when, just 30 seconds before ignition, the confused computer vetoed the firing. The puzzled Lyakhov was reporting the incident and musing over what to do next when the sensors suddenly indicated that orientation was indeed correct and fired the engines, seven minutes later than planned. This would have resulted in a landing far off course, possibly in Manchuria. Lyakhov routinely shut the engine down after six seconds.

Reasonably unconcerned, Soviet officials decided to attempt the retro-fire two orbits later using the back-up flight computer, thus plunging the mission into dangerous chaos. TM5 was the back-up spacecraft for the Bulgarian mission and the back-up computer still held the software for it. TM5’s inertial measurement unit was being

|

Portrait of the Soyuz TM6 crew. L to r: Mohmand, Lyakhov and Polyakov

|

used to orbit the spacecraft this time when suddenly the computer, programmed to perform a rendezvous manoeuvre burn instead, lit the engine for six seconds and shut it down, as programmed. Lyakhov, anxious to get home and unaware of the cause of the problem, manually re-ignited the engine and it fired for sixty seconds before the navigation computer sensed an attitude error and shut it down again.

In a normal retro-burn, the engine should have fired for 230 seconds and the crew was extremely fortunate that the engine shut down when it did and not later because it would have placed TM5 into an extremely low orbit. Had they been unable to orientate TM5 and get the confused computer to fire the engine, the cosmonauts would have been forced to separate the descent craft in preparation for a natural reentry which would have imposed abnormal loads on it. The crew would have burned up. Officials delayed the retro-fire for 24 hours and there was a danger that the crew could be stranded in space, to die when the limited environmental control system of the descent capsule ceased to work. There were emergency rations, but Lyakhov was more concerned about the rather basic lavatorial facilities. The toilet had been discarded with the OM, so they had to rely on plastic sleeves of the sleeping bag Mohmand had brought from Mir.

The back-up computer was reprogrammed with the correct retro-fire data to attempt a re-entry towards the prime recovery zone, and everything worked perfectly. Mission time was 8 days 20 hours 27 minutes. The extremely relieved Lyakhov suggested that in future the OM should not be jettisoned until after retro-fire, even though this would be costly in propellant, while the extremely unruffled Mohmand took it all in his stride, stating the crew were more tense than afraid. The Soviets admitted a lack of vigilance which had resulted from a sequence of successes. Lyakhov and Mohmand got away with it and the relatively good safety record for manned space flight remained.

Milestones

120th manned space flight

65th Soviet manned space flight

58th Soyuz manned space flight

5th Soyuz TM manned space flight

5th Soyuz international space flight

1st flight of an Afghan

1st failure of retro-rocket during burn

|

Int. Designation

|

1991-034A

|

|

Launched

|

18 May 1991

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 1, Site 5, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan

|

|

Landed

|

10 October 1991 (Artsebarsky on TM12);

25 March 1992 (Krikalev on TM13);

26 May 1991 (Sharman on TM11)

|

|

Landing Site

|

67 km southeast of Arkalyk

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

R7 (11A511U2); spacecraft serial number (7K-M) 062

|

|

Duration

|

144 days 15hrs 21 min 50 sec (Artsebarsky); 311 days 20 hrs 1 min 54 sec (Krikalev);

7 days 21 hrs 14min 20 sec (Sharman)

|

|

Call sign

|

Ozon (Ozone)

|

|

Objective

|

Delivery of the 9th main crew to Mir and operation of UK Juno programme by Sharman

|

Flight Crew

ARTSEBARSKY, Anatoly Pavolich, 34, Soviet Air Force, commander KRIKALEV, Sergei Konstantinovich. 32, civilian, flight engineer, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM7 (1988)

SHARMAN, Helen Patricia, 27, civilian, UK cosmonaut researcher

Flight Log

The agreement to fly a UK citizen to a Soviet space station originated in 1986, but was not signed until 1989. Financial problems dogged the project but in November 1989, four finalists were named. Sharman was named as primary candidate in February 1991, with Major Tim Mace of the British Army as her back-up. During the docking with the Mir complex, erroneous readings were produced by the rendezvous equipment. Artsebarsky had to dock manually, while Sharman operated cameras from the Descent Module and Krikalev observed the docking from the forward window in the Orbital Module. After performing a week of experiments focusing on medical tests, physical and chemical research, as well as contacting nine British schools by radio, Sharman returned to Earth with the Mir EO-8 crew on TM11. The landing on TM11 was very hard, with the capsule rolling several times and resulting in disorientation and bruising to the crew inside.

The primary objective of the ninth main Mir crew (EO-9) involved a construction programme, with up to eight EVAs planned for their five-month tour aboard the station. Their first task, however, was to relocate TM12 from the front to the aft port to permit the arrival of Progress M8. This was followed by the release of a small minisatellite, MAK-1, from the experiment airlock in the base block. MAK-1 was designed

|

The Soyuz TM12 prime crew of Artsebarsky (left), Sharman and Krikalev

|

to study Earth’s ionosphere, but a system failure rendered the satellite inoperable. The first of what turned out to be six EVAs by this crew (24 June, 4 hours 53 minutes) involved the removal and replacement of the failed Kurs approach system. EVA 2 (28 June, 3 hours 24 minutes) involved the deployment of the US-developed TREK device for studying cosmic rays. The other four EVAs (15 July, 5 hours 56 minutes; 19 July, 5 hours 28 minutes; 23 July, 5 hours 34 minutes and 27 July, 6 hours 49 minutes) focused on the construction of the Sofora girder structure. The crew deployed the Hammer and Sickle national flag of the USSR atop the girder during the sixth EVA, but Artsebarsky’s visor fogged up from his excursions during this EVA, requiring Krikalev to help him back to the hatch. The crew also continued space physics investigations, astrophysical observations, a range of technological experiments and observations of the Earth and its weather phenomena.

This five-month mission was flown at the time of the failed Soviet coup of August 1991 and the demise of the Soviet Union in the following months. Despite media reports suggesting he would be stranded alone in space, Krikalev was never “alone”. He was asked to remain on board the station when funding difficulties affected the flights of TM13 and TM14 later in the year. When the original crews of these two missions were merged into one new crew, only Alexander Volkov was qualified to remain on the station. Krikalev was asked to extend his mission until March when the next scheduled Russian resident crew would arrive. He agreed, and completed an unplanned nine-month stay in space as part of the EO-10 crew.

Milestones

141st manned space flight 71st Soviet manned space flight 64th Soyuz manned space flight 11th Soyuz TM flight 12th manned Mir mission 9th main crew

19th Soviet and 43rd flight with EVA operations 1st UK citizen (Sharman) in space 1st woman to visit Mir (Sharman)

Krikalev celebrates his 33rd birthday in space (27 Aug) Artsebarsky celebrates his 35th birthday in space (9 Sep)

1993-003A 13 January 1993 1993-003A 13 January 1993

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 19 January 1993

Runway 33, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

OV-105 Endeavour/ET-51/SRB BI-056/SSME #1 2019;

#2 2033; #3 2018

5 days 23hrs 38 min 19 sec

Endeavour

Deployment of TDRS-F by IUS-13; EVA operations, procedures and training exercise

Flight Crew

CASPER, John Howard, 48, USAF, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-36 (1990)

McMONAGLE, Donald Ray, 38, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-39 (1991)

RUNCO Jr., Mario, 39, USN, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-44 (1991)

HARBAUGH, Gregory Jordan, 35, civilian, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-39 (1991)

HELMS, Susan Jane, 33, USAF, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

The launch of STS-54 was delayed by just seven minutes over concerns about upper – atmospheric wind levels. The primary objective of the mission was the deployment of the sixth Tracking and Data Relay Satellite by IUS, which was accomplished on FD 1.This was the fifth successful deployment, with TDRS-B having been lost in the January 1986 Challenger accident.

Also located in the payload bay was the “hitchhiker experiment”, the Diffuse X-ray Spectrometer (DXS), which was designed to collect X-ray radiation data from diffuse sources in deep space. Despite some difficulties in operating this experiment, it did return good science data. Additional experiments included one to record microgravity acceleration, and a solid surface combustion experiment that recorded the rate of flame spread and the temperature of burning filter paper. A UV Plume Imager, mounted on a free-flying satellite, observed the orbiter and obtained data on the vehicle during controlled conditions. The crew also continued the long programme of photography of the Earth surface begun in the 1960s. This was catalogued at JSC as the Earth Observation Project, and liaised with various global scientific research

|

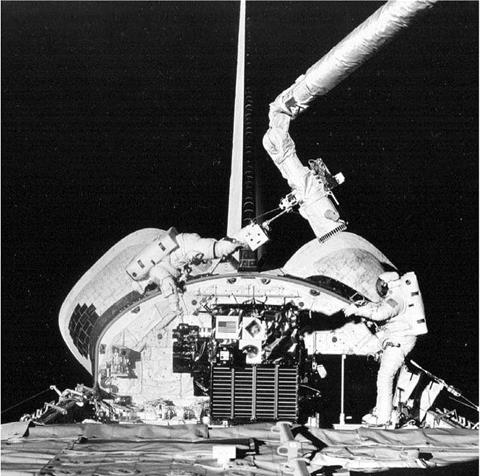

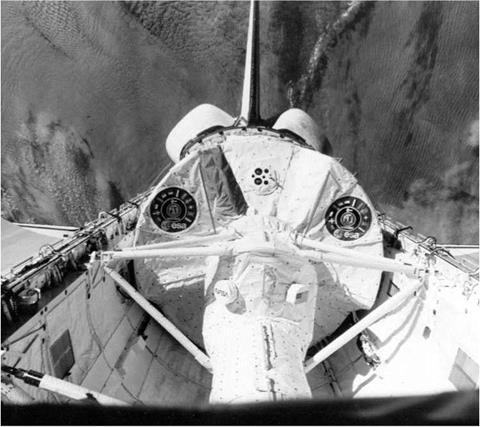

Harbaugh (back to camera) carries Runco along the starboard side of Endeavour’s payload bay during the 17 January EVA. He is evaluating the ability of astronauts to move a “bulky” object about in space by hand

|

efforts, allowing Shuttle crews to document specific features and phenomena of interest.

The FD 5 EVA (17 Jan, 4 hours 28 minutes) was the first of a series of EVAs planned for the next three years, leading up to start of space station construction (planned at that time to be 1996). With only two missions having included EVA operations since the return to flight in 1988, there was an urgent need to develop experience, techniques and procedures on extensive EVA operations prior to constructing the space station. On STS-54, the two EVA astronauts (Harbaugh EV1 and Runco EV2) tested their ability to freely move around the payload bay, to climb into the foot restraints without using their hands, and to simulate carrying large objects in the microgravity environment. This was also useful in evaluating the possibility of rescuing an incapacitated crew member during an EVA. They also evaluated the differences and similarities in these tasks between training simulations and actual orbital operations. After the EVA, they answered detailed questions on their experiences and, following the mission’s return to Earth (which was delayed by one orbit due to ground fog at the Cape), went back into the WETF to evaluate the tasks again, for comparison with the actual EVA and to help improve future training procedures.

The crew also participated in the Physics of Toys experiment during a 45-minute live TV transmission. Staff at the Museum of Natural Science helped to develop the course, which was designed to generate interest in science at schools. The toys were selected by a team of physicists. The Physics of Toys experiment was a follow-on to the Toys in Space package flown on STS 51-D in 1985.

Milestones

157th manned space flight

83rd US manned space flight

26th US and 48th flight with EVA operations

53rd Shuttle mission

3rd flight of Endeavour

6th TDRS deployment mission

|

|

|

Int. Designation

|

1995-004A

|

|

Launched

|

3 February 1995

|

|

Launch Site

|

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida

|

|

Landed

|

11 February 1995

|

|

Landing Site

|

Runway 15, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida

|

|

Launch Vehicle

|

OV-103 Discovery/ET-68/SRB BI-070/SSME #1 2035; #2 2109; #3 2029

|

|

Duration

|

8 days 6 hrs 28 min 15 sec

|

|

Call sign

|

Discovery

|

|

Objective

|

Mir Rendezvous (near-Mir) mission; SpaceHab 3; EVA Development Flight Test

|

Flight Crew

WETHERBEE, James Donald, 42, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-32 (1990); STS-52 (1992)

COLLINS, Eileen Marie, 38, USAF, pilot

HARRIS Jr., Bernard Anthony, 38, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-55 (1993)

FOALE, Colin Michael, 38, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-45 (1992); STS-56 (1993)

VOSS, Janice Elaine, 38, civilian, mission specialist, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-57 (1993)

TITOV, Vladimir Georgievich, 48, Russian Air Force, Russian mission specialist 4, 3rd mission

Previous missions: Soyuz T8 (1983); Soyuz T10 launch pad abort (1983); Soyuz TM4 (1987)

Flight Log

As originally planned, Mir should have been visited by the Soviet Space Shuttle Buran but when the first Shuttle finally reached the space complex, it was an American, not a Russian one. The STS-63 mission achieved a number of milestones in space history for both the US and the Russian space programmes, and was another significant step towards cooperative efforts for the forthcoming ISS. With only a five-minute window to rendezvous with Mir, Discovery’s countdown was refined to include additional holding time at the T — 6 hour and T — 9 minute points. The 2 February launch was postponed at T — 1 day when one of the three IMUs on Discovery failed.

Starting on FD 1, a series of thruster burns brought Discovery to a rendezvous with Mir on FD 4. The approach was expected to be as close as 10 metres, but with three of the Shuttle’s 44 RCS thrusters used for small manoeuvres leaking prior to

|

Astronaut Foale (on the RMS) attempts to grab the SPARTAN 204 as Harris looks on during the first EDFT EVA. The roof of the SpaceHab module is in foreground

|

rendezvous, the Russians voiced some concerns and it took some considerable discussions and exchange of technical information to convince them that it was safe to proceed. Wetherbee brought the Shuttle to a station-keeping distance of 122 metres, then closed to about 11.2 metres with the crews excitedly talking to each other. Cosmonaut Titov, who was aboard Discovery, had spent over a year on Mir in the late 1980s and talked extensively with his colleagues on the station. This was the first time American and Russian spacecraft had been this close for almost 20 years and the next step in the schedule was the planned docking of STS-71 in June. For now, the close approach was a useful demonstration of a skill that American astronauts had not used in conjunction with another manned spacecraft since the Apollo era – proximity operations. Discovery was eventually withdrawn back to 122 metres and Wetherbee executed a one-and-a-quarter orbit loop around Mir as the astronauts conducted a detailed photographic survey of the station. On board Mir, the EO-17 crew reported no vibrations or movement of the station’s solar array panels during the manoeuvres. This was an excellent start to Shuttle-Mir operations and is often termed the near-Mir mission.

In addition to the Mir rendezvous, STS-63 featured the usual complement of middeck and payload bay secondary experiments, plus the third flight of SpaceHab. This flight of the commercially-developed augmentation module included 20 experiments, with 11 biotechnology experiments, three advanced materials development experiments, four demonstrations of technology and a pair of hardware experiments supporting acceleration technology. In past flights, crew time was taken up with caretaking the experiments but on this flight, developments in remote monitoring and data transfer reduced direct crew involvement and allowed principle investigators to monitor and control their own experiments. A new robotic device to change samples, called Charlotte, was also flown as an evaluation of automated systems that would allow the crew to focus their efforts on other areas of the flight plan. SPARTAN-204 was lifted out of the cargo bay on FD 2 by the RMS and would study the orbiter glow phenomena and firings of the jet thrusters on the Shuttle. It was later released for a 40-hour free-flight, during which time its Far UV Imaging Spectrograph studied a range of celestial targets in interstellar space.

The SPARTAN was also planned to be used during the EVA towards the end of the mission. The EVA (9 Feb, 4 hours 39 minutes) was the first in a series of EVA Development Flight Test objectives designed to prepare NASA for ISS assembly activities. Harris (EV1) and Foale (EV2) were meant to handle the 1,134kg SPARTAN payload to rehearse ISS assembly techniques for translating large masses, but both astronauts reported feeling cold while at the end of the RMS, despite modifications in their suits to keep them warm when away from the somewhat protected environment of the payload bay. One of the final objectives of STS-63 was to test the revised landing surface at the Shuttle Landing Facility. This was expected to decrease wear on the tyres and give the orbiters a better chance of landing in crosswinds, thus offering a greater range of landing opportunities at the Cape to help maintain processing schedules and to meet the launch windows of a tight manifest. Upon landing, the crew received congratulations from the cosmonauts on Mir. The once-independent US and Russian manned space programmes were beginning to merge into one international programme for ISS and this mission was an important step towards that goal.

Milestones

176th manned space flight 97th US manned space flight 67th Shuttle mission 20th flight of Discovery

31st US and 56th flight with EVA operations

1st orbiter to complete 20 missions

1st approach/fly-around with Mir by US Shuttle

1st female Shuttle pilot

2nd Russian cosmonaut on Shuttle

1st EDFT excursion

3rd SpaceHab mission

1st African American to perform EVA (Harris)

1997-032A 1 July 1997 1997-032A 1 July 1997

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida 17 July 1997

Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, KSC, Florida OV-102 Columbia/ET-86/SRB BI-088/SSME #1 2037; #2 2034; #3 2033 15 days 16hrs 34 min 4 sec

Columbia Objective Material Science Laboratory 1 (Re-flight)

Flight Crew

HALSELL Jr., James Donald, 40, USAF, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-65 (1994); STS-74 (1995); STS-83 (1997)

STILL, Susan Leigh, 35, USN, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-83 (1997)

VOSS, Janice Elaine, 40, civilian, mission specialist 1, payload commander,

4th mission

Previous missions: STS-57 (1993); STS-63 (1995); STS-83 (1997) GERNHARDT, Michael Landen, 40, civilian, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-69 (1995); STS-83 (1997)

THOMAS, Donald Alan, 41, civilian, mission specialist 3, 4th mission Previous missions: STS-65 (1994); STS-70 (1995); STS-83 (1997)

CROUCH, Roger Keith, 57, civilian, payload specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-83 (1997)

LINTERIS, Gregory Thomas, 39, civilian, payload specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-83 (1997)

Flight Log

The 84-day turnaround from the landing of STS-83 to the launch of the re-flight mission, designated STS-94, was a new record and an impressive demonstration of the ability and skills of the processing team. The quick turnaround was in part facilitated by servicing the MSL payloads while still in the payload bay of Columbia. The original STS-94 mission was manifested as a “flight opportunity” by Discovery in October 1998, but as no payload had been assigned to that flight, it was the first available flight number to assign the MSL administration and planning documents to. As the same vehicle, crew and payload would be flying, it was in effect a “paper change” to the flight designation, although a new ET, SRBs and different SSMEs were

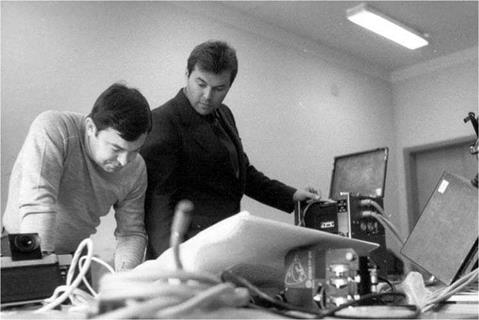

|

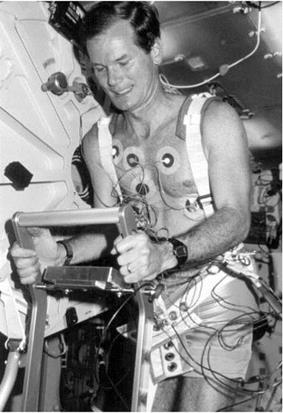

Susan Still (left) and Janice Voss review In-flight Maintenance (IFM) procedures during one of the daily planning sessions in the Spacelab Science Module in support of the MSL mission. Meanwhile Greg Linteris works at a laptop computer in the background

|

assigned to support the new mission. There was a delay to the launch due to unacceptable weather around the SLF.

With the crew operating the familiar Red and Blue two-shift system, 33 investigations were completed in the fields of combustion, biotechnology and materials processing. There were 25 primary investigations, four glove box investigations and four accelerometer studies on MSL-1. Some of this work involved evaluating hardware, facilities and procedures in preparation for similar hardware and research programmes that were due to be carried out on ISS. Within the combustion investigations, 144 experiments were planned, and over 200 were actually completed. The TEMPUS electromagnetic containerless processing facility completed over 120 melting cycles of zirconium at temperatures ranging between 340 and 2,000° C. In the “ignition of large fuel droplets” experiment, conducted in the glove box, only 52 test runs were planned, but the crew managed to complete 125 by the end of the mission. There were in excess of 700 crystals of various proteins grown during the 16-day mission and a record number of commands (over 35,000) were sent from the Spacelab Mission Operations Control Center at Marshall Space Flight Center to the MSL-1 experiments.

On 2 July, Don Thomas reported sighting the Mir space station as it passed within 100 km of Columbia. Two days later, as America celebrated Independence Day, the crew sent messages of congratulations to the JPL Pathfinder team in California on the successful landing of the Mars Pathfinder spacecraft on the Red Planet. Three days later, the crew were informed of the successful docking of a Russian Progress (M35) re-supply vehicle with Mir and the following day, Halsell, Gernhardt and Voss used the SAREX equipment aboard Columbia to talk with Mike Foale aboard the Mir space station. On 14 July, the crew reported a minute debris impact with one of the overhead windows, a familiar occurrence which again was no cause for concern over safety. Shuttle windows are often hit by small pieces of space debris during orbital flight. Being multi-layer panels, such small impacts are highly unlikely to jeopardise the integrity of the window or the safety of the crew and vehicle.

Milestones

199th manned space flight 115th US manned space flight 85th Shuttle mission 23rd flight of Columbia

1st re-flight of same vehicle, payload and crew 15th flight of Spacelab Long Module 11th EDO mission

Flight Crew

PADALKA, Gennady Ivanovich, 40, Russian Air Force, Russian ISS-9 and Soyuz commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz TM28 (1998)

FINCKE, Edward Michael, 37, USAF, ISS-9 science officer KUIPERS, Andre, 45, civilian, ESA Soyuz flight engineer

Flight Log

For the ninth main expedition to the ISS, the crew would conduct a programme of 24 US and 42 Russian experiments. Many of these were continuations of experiments delivered before the loss of Columbia, but there were four new investigations. The crew’s flight plan envisaged 130 sessions, or over 200 hours, focusing on science on the station, in addition to the routine housekeeping and maintenance chores. During the first week aboard the station, the new resident crew worked with the outgoing ISS-8 crew and with Dutch astronaut Andre Kuipers, who had a package of ESA experiments under the Dutch Expedition for Life sciences, Technology and Atmospheric (DELTA) research programme. His research included five physiological experiments, five biology experiments, single investigations in microbiology, physical sciences, and Earth observations, three technology demonstrations and five educational projects. Kuipers completed his programme and returned to Earth with the ISS-8 crew on 30 April aboard TMA3.

Settling down to their own programme, the ISS-9 crew received no visiting crews but did receive the payloads delivered on Progress M1-11, M49 and M50. All the EVAs from this expedition were conducted from the Pirs module using Russian Orlan M suits. After working on suit repairs and servicing for over a month, their first EVA (24 Jun) was abandoned after 14 minutes because of a pressure drop in the main oxygen bottle of the Orlan M suit. Following successful repairs, the crew conducted

|

The TMA4/ISS-9 crew inside the ISS; 1 to r Padalka, Fincke and Kuipers

|

their first full EVA on 30 June (5 hours 40 minutes), during which a new circuit breaker was installed on the S0 Truss to power one of the four CMG. During the next excursion (3 Aug for 4 hours 30 minutes), the crew installed reflectors and communication units ready for the first ESA Automatic Transfer Vehicle (ATV, named “Jules Verne”), which is designed to carry seven tons of supplies to the station, boost the station’s orbit, and remove waste materials for atmospheric burn-up. The first flight was planned for 2006 but was subsequently delayed to 2007 or 2008. The final ISS-9 excursion (3 Sep for 5 hours 21 minutes) saw the crew install three antennas to support the ATV docking on the rear port of the Zvezda module, and fit further handrails and tether guides for future EVAs.

On 18 June, Michael Fincke made space history by becoming the first US astronaut to become a father while in space. In Houston, his wife gave birth to their second daughter, with the astronaut listening to the delivery via his wife’s cell phone and a relayed radio link through MCC-Houston. A video of the event was later sent up to the proud father.

The crew spent a significant amount of time in repairing onboard equipment, and Fincke also conducted troubleshooting diagnostics on the American EMU units after the previously reported cooling problems had been traced to water circulation pumps located inside the suits’ integrated backpacks. Fincke removed the pump and videoed it for ground specialists to analyse the problem, but the pictures failed to reveal any

obvious causes of the malfunction. Two new pumps were manifested for delivery on the next Progress mission (M50).

The crew also had ongoing problems with the Elektron oxygen generator that had been playing up for some time. Earlier in the ISS-9 residency, it briefly shut down twice, and by late August it would fail every three days or so and require a manual restart. These shutdowns were found to be centred on the liquid units (BZh in Russian) that held trapped gas inside micro-pumps, despite using purified water. The unit was put into a mode to increase oxygen production, which would raise the internal pressure of the station so that, should the unit need repairing, a lengthy shut-down would be possible without too much risk to the crew. These extensive repairs were conducted during September, with the crew installing an older unused unit, before eventually replacing the units to improve the performance of the Elektron system (although problems still remained as their residency drew to a close).

The crew completed their programme with several other maintenance tasks and returned to Earth with Russian test cosmonaut Yuri Shargin in October.

Milestones

241st manned space flight

97th Russian manned space flight

90th manned Soyuz mission

4th manned Soyuz TMA mission

37th Russian and 91st flight with EVA operations

8th ISS Soyuz mission (8S)

6th visiting mission (VC-6)

3rd resident caretaker ISS crew (2 person)

Before the next exchange of ISS resident crews occurred in October 2004, the first privately funded, non-government manned space flight took place – the sub-orbital flights of Spaceship One that won the Ansari X-Prize. These flights are covered in the Quest for Space chapter (Chapter 2).

| |

1993-003A 13 January 1993

1993-003A 13 January 1993

1997-032A 1 July 1997

1997-032A 1 July 1997