SOYUZ 6, 7 AND 8

![]()

1969-085A (Soyuz 6), 086A (Soyuz 7), 087A (Soyuz 8)

1969-085A (Soyuz 6), 086A (Soyuz 7), 087A (Soyuz 8)

11 (Soyuz 6), 12 (Soyuz 7) and 13 (Soyuz 8) October 1969 Pad 1, Site 5 (Soyuz 7); Pad 31, Site 6 (Soyuz 6, Soyuz 8), Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan 16 (Soyuz 6), 17 (Soyuz 7) and 18 (Soyuz 8) October 1969 Soyuz 6 – 179.2 km (111 miles) northwest, Soyuz 7 – 153.6 km (95 miles) northwest and Soyuz 8 – 144 km (89 miles) north of Karaganda R7 (11A511) for all three launches; spacecraft serial numbers (7K-0K) #14 (Soyuz 4); #15 (Soyuz 5);

#16 (Soyuz 8)

4 days 22hrs 42 min 47 sec (Soyuz 6); 4 days 22hrs 40 min 23 sec (Soyuz 7); 4 days 22hrs 50 min 49 sec (Soyuz 8) Soyuz 6 – Antey (Antaeus); Soyuz 7 – Buran (Snowstorm); Soyuz 8 – Granit (Granite)

Soyuz “troika” group flight; rendezvous and docking between Soyuz 7 and 8; space welding experiments on Soyuz 6

Flight Crew

SHONIN, Georgy Stepanovich, 34, Soviet Air Force, commander Soyuz 6 KUBASOV, Valery Nikoleyevich, 34, civilian, flight engineer Soyuz 6 FILIPCHENKO, Anatoly Vasilyevich, 41, Soviet Air Force, commander, Soyuz 7

VOLKOV, Vladislav Nikoleyevich, 33, civilian, flight engineer Soyuz 7 GORBATKO, Viktor Vasilyevich, 34, Soviet Air Force, research engineer, Soyuz 7

SHATALOV, Vladimir Aleksandrovich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander Soyuz 8 and group commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: Soyuz 4 (1969)

YELISEYEV, Aleksey Stanislovich, 35, civilian, flight engineer Soyuz 8, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz 5 (1969)

Flight Log

Soyuz 6 was to have been a solo mission but was flown together with Soyuz 7 and 8 which were to perform a Soyuz 4/5-type rendezvous, docking and transfer mission. Soyuz 6 – without a docking probe – set off first at 16: 10 hrs local time on 11 October. It carried two cosmonauts, Shonin and Kubasov, and entered a 51.7° inclination

|

The Soyuz 6 crew of Kubasov (left) and Shonin |

orbit, which would, after four manoeuvres, reach a maximum altitude of 242 km (150 miles). Their objectives were the usual Soviet ones of “testing, checking, perfecting and conducting” plus a unique experiment called Vulcan, in which automatic welding would be attempted inside the unpressurised Orbital Module. On the 77th orbit of Soyuz 6, three processes were attempted: electron beam, fusible electrode and compressed arc welding, under the control of Kubasov. The samples were returned to Earth. In 1990, some 21 years later, it was revealed that the low-pressure compressed arc had inadvertently almost burned a hole right through the inner compartment flooring and damaged the hull of the Orbital Module. The crew were at first unaware of this as they were sealed in the DM during the welding operation, but found the damage when they entered the OM towards the end of their mission.

When Soyuz 7 was launched at 15: 45 hrs local time from Baikonur the day after, most observers felt that a docking was likely since, at the time, it was not known that

|

The crews of Soyuz 6-8 pose for a “group shot”. Back row from left: Gorbatko, Filipchenko and Volkov (Soyuz 7). Front row from left: Kubasov and Shonin (Soyuz 6), Shatalov and Yeliseyev (Soyuz 8) |

Soyuz 6 could not do so. Indeed, one of Soyuz 7’s stated objectives was “manoeuvring and navigation tests” with Soyuz 6. But Filipchenko, Gorbatko and Volkov were supposed to dock not with Soyuz 6 but with Soyuz 8, which was duly launched at 15: 19 hrs local time on 13 October, with Shatalov and Yeliseyev, the first Soviet space – experienced crew.

Problems with the Igla rendezvous system were experienced, and a manual attempt at docking was not successful. The nearest the two craft came to one another was 487m (1,600ft), observed for 4 hours 24 minutes by Soyuz 6 from about 1.6km (1 mile) away. Maximum altitudes achieved by Soyuz 7 and 8 were 244 and 235 km (152 and 146 miles) respectively during their missions which, with Soyuz 6, entailed detailed Earth and celestial observations under the group command of Shatalov.

The “mystery missions”, which in total involved 31 orbital change manoeuvres, ended on 17, 18 and 19 October, 179.2km (111 miles) northwest, 153.6km (95 miles) northwest and 144 km (89 miles) north of Karaganda respectively.

Milestones

34th, 35th and 36th manned space flights 13th, 14th and 15th Soviet manned space flights 1st three-manned-spacecraft mission 1st time with seven people in space at once

Shortest turnaround between missions – ten months, for Shatalov and Yeliseyev

|

Flight Crew

CONRAD, Charles “Pete” Jr., 39, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: Gemini 5 (1965); Gemini 11 (1966)

GORDON, Richard Francis Jr., 40, USN, command module pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: Gemini 11 (1966)

BEAN, Alan LaVern, 37, USN, lunar module pilot

Flight Log

Flying to the Moon a second time wasn’t any easier, but it seemed that way after the euphoria of Apollo 11. Indeed, Apollo 12 had two particular hazards, one deliberate and one unpredictable but none the less avoidable. The deliberate hazard was to be the hybrid trajectory to the Moon, which did not guarantee Apollo 12 a “free return’’ by lunar loop if there was a major systems failure en route. The second hazard could have been avoided had NASA not decided to launch the mighty Saturn V in heavy rain and dark storm clouds, seemingly to please the space budget-cutter, President Richard Nixon, who had come to the KSC to watch.

About 36 seconds after 11: 22 hrs local time, with the Saturn already out of view, Pad 39A was hit by lightning. So was Apollo 12. Commander Conrad saw the multicoloured control panel displaying systems shorts and said that it seemed that “everything in the world had dropped out.’’ LMP Bean restored systems as the second and third stages proceeded effortlessly into 199 km (124 miles) 32° orbit. All the electrical circuits were checked and the go for the Moon was given. The S-IVB burned for 5 minutes 45 seconds and the transposition and docking manoeuvre was successful, but the S-IVB was placed into an unusual and highly elliptical orbit of the Earth, rather than into solar orbit, due to a malfunction.

The TV shows were jocular and informative. Conrad and Bean checked out the Lunar Module, and one mid-course correction was made to place Apollo out of the free return and on course for a lunar orbit with desirable lighting conditions at the landing point. Apollo 12’s SPS lit up on the lunar far side and placed the spacecraft

|

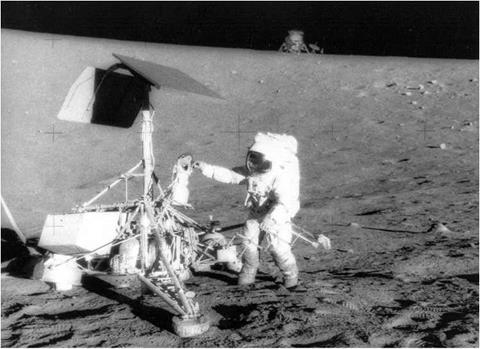

Pete Conrad examines the Surveyor 3 spacecraft. The Apollo 12 Lunar Module can be seen on the horizon. |

into a 110 by 312 km (68 x 194 miles) orbit, which was adjusted two orbits later to an eventual 110 km (68 miles). At T + 107 hours 54 minutes, the Lunar Module became Intrepid and the Command Module Yankee Clipper, illustrating that this was an allNavy crew. DOI began at T + 109 hours 23 minutes with a 29-second firing placing Intrepid at a perilune of 14.4 km (9 miles) for the PDI. Before this, there was hectic activity between the ground and the crew to update the LM’s navigation programme, which continued two minutes into the burn that began at T + 110 hours 20 minutes.

The high-spirited crew came into their Ocean of Storms landing site, close to the unmanned Surveyor 3 spacecraft which had landed there in 1967. Conrad landed Intrepid about 856 m (2,808 ft) northwest of Surveyor at T + 110 hours 32 minutes at 3°11’51" south 23°23’7.5" west. CMP Gordon spotted both Intrepid and Surveyor from orbit in Yankee Clipper. The first moonwalk began at T + 115 hours 10 minutes when the jocular Conrad hopped, skipped and hummed across the surface. After joining him, Bean took the colour television camera to place it on a tripod, but the camera was pointed at the Sun and blacked out. The by now dwindling TV audiences switched off.

The first 3 hour 56 minute EVA on 19 November involved erecting the US flag and deploying the first ALSEP array of lunar experiments, one of which was powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator with a radioactive fuel source. The second

EVA on 20 November, lasting 3 hours 49 minutes, was highlighted by the visit to Surveyor, bits of which were cut off to be taken home for analysis. Conrad’s fall in the lunar dust caused a “spacesuit might leak’’ scare, but from the antics of later moon – walkers, one wonders what the fuss was about.

The highly successful moonwalks over, after 31 hours 31 minutes on the Moon, Intrepid sailed for Yankee Clipper. The rendezvous and docking 3 hours 30 minutes later was watched live by TV audiences, who could even see Intrepid’s crew in the windows of the LM and the little spurts of the RCS jets. Conrad and Bean removed their dusty spacesuits and crossed into Yankee Clipper naked, except for their headsets. Intrepid was sent crashing into the Moon and the reverberations from the impact were picked up by the ALSEP seismometer now on the surface.

Yankee Clipper broke anchor after 45 orbits and 88 hours 56 minutes over the Moon. The crew witnessed a spectacular solar eclipse on the way home and splashed down near USS Hornet at 15° south 165° west at T + 10 days 4 hours 36 minutes 25 seconds. Like the Apollo 11 crew, Conrad, Gordon and Bean had to live in the Apollo quarantine container for three weeks to ensure that no “moon bugs’’ came home with them.

Milestones

37th manned space flight

22nd US manned space flight

6th manned Apollo flight

6th Apollo CSM manned flight

4th Apollo LM manned flight

4th manned flight to and orbit of the Moon

2nd manned lunar landing and moonwalk

1st manned mission with two EVAs

1st manned spacecraft to spend a day on the Moon

1st manned mission to use radioisotope thermoelectric generators

8th US and 10th flight with EVA operations

|

Flight Crew

LOVELL, James Arthur Jr., 42, USN, commander, 4th mission Previous missions: Gemini 7 (1965); Gemini 12 (1966); Apollo 8 (1968) SWIGERT, John Leonard “Jack” Jr., 39, command module pilot HAISE, Fred Wallace Jr., 36, lunar module pilot

Flight Log

Command module pilot Thomas “Ken” Mattingly had the bad luck, two days before the flight of Apollo 13, to be declared not immune to the German measles that he had been exposed to by back-up LMP Charlie Duke. He was dropped and replaced by back-up Jack Swigert, who was put through his paces in the simulator to ensure his readiness and compatibility with the remaining prime crew members, James Lovell and Fred Haise. Lift-off seemed routine at 14: 32hrs local time, but the Saturn V burn lasted 44 seconds longer, because the four remaining engines of the S-II had to burn for an extra 34 seconds to make up for the loss of the fifth one, and the S-IVB had to burn for an additional ten seconds.

Initial orbit of 33.5° and 156 km (97 miles) apogee was achieved. The S-IVB ignited, the transposition and docking was successful and the stage was sent towards an impact on the Moon, big enough to be detected by the Apollo 12 seismometer. The television pictures were of high quality, but were not shown live by any network. Apollo 13 indeed seemed a milk run to the Moon, targeted for the Fra Mauro highlands. Then, at T + 55 hours 55 minutes 20 seconds on 13 April, oxygen tank No. 2 in the Service Module, which had undetected heater switches welded together due to an electrical malfunction in a pre-launch test, exploded 328,000 km (222,461 miles) from Earth.

The reaction of the crew was calm and stoic as they faced a lingering death in space. Power was going down fast in the Command Module. The only hope was to use the LM Aquarius, thankfully still attached, as it was the trans-lunar coast rather than

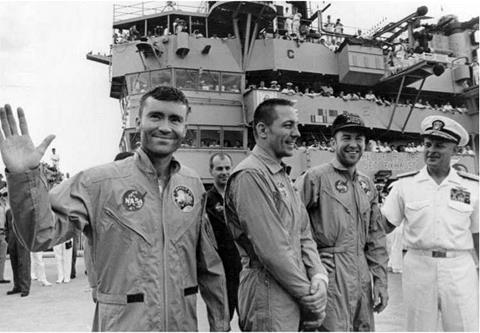

|

Apollo 13 crew (1 to r) Haise, Swigert and Lovell, relieved to be back on Earth after a trying mission |

the return journey. Aquarius’s descent engine was used three times, T + 61 hours 30 minutes, for 30 seconds, to get Apollo 13 back on a lunar looping “free return’’ trajectory which would at least guarantee making landfall on Earth – somewhere, hopefully in the Indian Ocean: for 4 minutes 28 seconds to speed the return journey, at T + 142 hours 53 minutes; and for 15.4 seconds to fine-tune the trajectory. Rookies Haise and Swigert had strained at their windows to get a peek at the lunar far side during the lunar loop, which made them and Lovell the farthest travellers from Earth, at a distance of 397,848 km (247,223 miles).

Conditions on board were pitiful. It was extremely cold and the spacecraft was operating on the power equivalent of a single light bulb by the end of the mission. The crew, ably supported by thousands of engineers, scientists and fellow astronauts on the ground, even had to jury-rig an air conditioning unit to get rid of carbon dioxide. Aquarius was separated just before re-entry, followed by the Service Module, giving the incredulous crew their first view of the devastation that had been below them. Left with a little battery power, the Command Module Odyssey limped home to a splashdown at T + 5 days 22 hours 54 minutes 41 seconds, close to the USS Iwo Jima at 21° south 165°west. The shortest US three-person flight in history had captured the hearts of the world, and ended with a service of thanksgiving on the recovery ship.

The events of Apollo 13, as well as a tightening of the NASA budget, helped to seal the fate of future missions. Apollo 20 had already been axed in January 1970, and

by September, Apollo 15 and 19 had been cancelled and the remaining missions renumbered to end with Apollo 17. The fear of losing a crew in space, or of their being stranded on the Moon with no hope of rescue, and the desire to move on to new programmes closer to Earth, together with the escalating cost of the war in southeast Asia and social unrest in the United States, all contributed to the end of the Apollo lunar programme.

Milestones

38th manned space flight

23rd US manned space flight

7th Apollo manned space flight

7th Apollo CSM manned flight

5th Apollo LM manned flight (docked only)

5th manned flight to the Moon

1st manned lunar loop flight

1st aborted lunar landing mission

1st flight by crewman on fourth mission

1st flight by crewman on second Moon mission