STS-7

|

Int. Designation |

1983-026A |

|

Launched |

18 June 1983 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

24 June 1983 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 15, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-099 Challenger/ET-7/SRB A51; A52/SSME #1 2017; #2 2015; #3 2012 |

|

Duration |

6 days 2 hrs 23 min 59 sec |

|

Callsign |

Challenger |

|

Objective |

Commercial satellite deployment mission; space adaptation medical investigations |

Flight Crew

CRIPPEN, Robert Laurel, 45, USN, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-1 (1981)

HAUCK, Frederick “Rick” Hamilton, 42, USN, pilot FABIAN, John McCreary, 44, USAF, mission specialist 1 RIDE, Sally Kristen, 32, civilian, mission specialist 2 THAGARD, Norman Earl, 39, civilian, mission specialist 3

Flight Log

By contrast to the Soviet reaction to the flight of Svetlana Savitskaya in 1982, the US launch of Sally Ride was played down as much as possible by NASA and by the lady herself, not with total success. The on-time lift-off occurred at 07: 33 hrs local time and after MECO, two OMS burns were required to carry Challenger to its operational 28.45° orbit with a maximum altitude of 272 km (169 miles). Crippen, the first person to fly the Shuttle for a second time, described the launch as a bit smoother than he remembered on STS-1.

The first commercial satellite payload was delivered into orbit at T + 9 hours 29 minutes, with an accuracy estimated at within 457 m (1,500 ft) of the target point and within 0.085° of the required pointing vector. Canada’s Anik 2C later made its way into geostationary orbit. The following day, satellite number two, India’s Palapa, was safely deployed. With the commercial trucking mission over, the crew got down to the third satellite deployment, that of the West German SPAS free flier, using the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm operated by John Fabian. Almost immediately, Fabian grabbed the satellite, demonstrating the first satellite retrieval. SPAS was released again and Crippen moved Challenger 300 m (984 ft) away and performed a series of station-keeping manoeuvres. Cameras on SPAS, meanwhile, took spec-

|

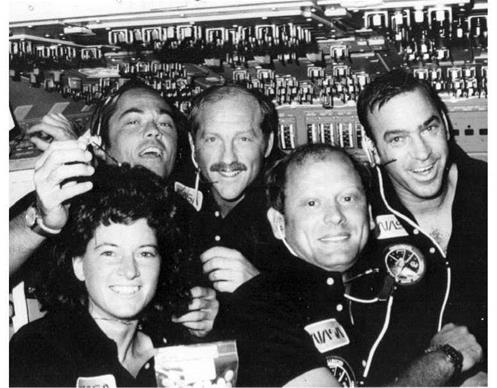

Clockwise from top left: Crippen, Hauck, Fabian, Thagard and Ride, the crew of STS-7 |

tacular photos of Challenger in space, with the RMS arm conveniently cocked in the shape of a number 7.

Six science experiments were on board and these operated for nine-and-a-quarter hours autonomously before the free flier was retrieved, this time by Sally Ride. The third mission specialist, the flight doctor Norman Thagard, who had been added to the crew to study space adaptation syndrome, even had a go at using the RMS. A complement of onboard experiments was operated by the crew, including the first demonstration of the Shuttle’s Ku-band rendezvous radar system and a reduction in cabin pressure from 760 mm (3in) to 527 mm (2 in) for 30 hours to investigate the possibility of eliminating the required three-and-a-half hours pre-breathing period for EVA astronauts.

The high point of the mission was to be Challenger’s return to the Kennedy Space Center, the first such return to launch site in history. Bad weather thwarted the attempt and Crippen was diverted to Edwards Air Force Base to land on runway 15. His request for a two day orbital extension was turned down because of concerns over one of the APUs on Challenger. Mission time was T + 6 days 2 hours 23 minutes 59 seconds.

Milestones

91st manned space flight 38th US manned space flight 7th Shuttle flight 2nd flight of Challenger 1st flight with five crew 1st US female in space

|

Flight Crew

LYAKHOV, Vladimir Afanasevich, 42, Soviet Air Force, commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: Soyuz 32 (1979)

ALEKSANDROV, Aleksandr Pavlovich, 40, civilian, flight engineer

Flight Log

Following the docking failure of Soyuz T8, the next crew were assigned to complete most of the tasks planned for the previous one. However, Titov and Strekalov had conducted extensive EVA training which the T9 crew had not, so the plan was to launch Soyuz T10 with Titov and Strekalov aboard to take over from the T9 crew and conduct the extensive EVAs they had trained for.

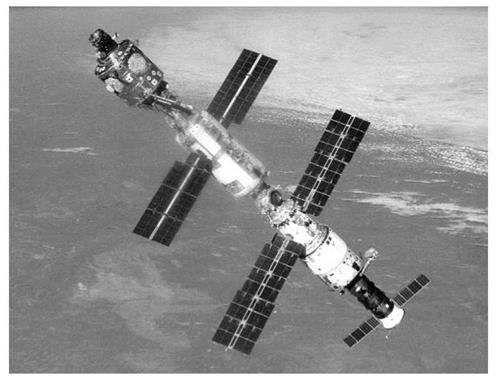

Soyuz T9, with a crew of two rather than the expected three (due to additional propellant load), took off from Baikonur at 15: 12hrs local time, and just over a day later docked at the rear of Salyut 7 to start a mission that would, according to mission controller Valery Ryumin, be shorter than Soyuz T5’s 211 days. They almost did not make it as, for the first time since Soyuz 1, one of the twin solar panels on Soyuz failed to deploy (although this did not prevent the docking with the Salyut), a fact not revealed for 20 years. The crew, Vladimir Lyakhov and rookie flight engineer Aleksandr Aleksandrov, were the first to operate using a Heavy Cosmos module, No.1443, attached to the front of Salyut 7. This two-part spacecraft contained a 1.5 m3 (50 ft3) habitable module, an Instrument Module, and a descent capsule capable of returning 500 kg (1,103 lb) to Earth. The module was equipped with 38 m2 (40 ft2) of solar panels, providing 3 kW of electricity.

Lyakhov and Aleksandrov got down to work producing virus cells and conducting Earth resources surveys, saving Soviet citizens from disaster by warning of the formation of a lake from a melting glacier which threatened to flood several towns beneath. While the crew were inside Soyuz T9 conducting a mock evacuation exercise,

|

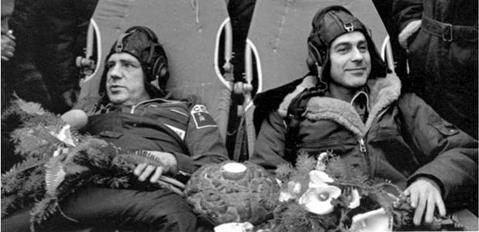

With a traditional traveller’s gift of bread and salt (as well as flowers), the T9 crew relax after their recovery from the mission. Lyakhov is on the left, Alexandrov on the right |

one of Salyut’s 14mm (1 in) thick windows was pitted to a depth of 4mm (0.16 in) by the impact of an unidentified object.

Cosmos 1443 separated from Salyut 7 on 14 August and, while flying autonomously, returned its descent capsule containing film and some equipment. It landed 100 km (62 miles) southeast of Arkalyk on 23 August. The major part of Cosmos was destroyed during re-entry on 19 September. Soyuz T9 had been flown from the back of Salyut to the front to prepare for the arrival of Progress 17 on 19 August. Progress left on 17 September, leaving the port free for the Soyuz T10 crew, who were to have been launched on 27 September to help with repairs, including an EVA to correct solar panel problems and add additional panels to increase the electrical supply on board the station.

By this time, Salyut 7 was in pretty bad shape, propellant leaks leaving the station with little manoeuvrability. Salyut’s back-up main engine was also crippled and a solar panel failure had reduced solar power. A major incident occurred on 9 September during the refuelling operations by Progress 17. A Salyut fuelling line used to feed oxidiser from the Progress to the Salyut ruptured. With only half of the 32 thrusters working, it seemed likely Salyut would have to be abandoned, but a decision was made to work around the problem and let the current mission continue while options for repair were evaluated. After the Soyuz T10 crew failed to reach orbit following the first on-the-pad launch abort in history, rumours spread in the west that Lyakhov and Aleksandrov were stranded in space, particularly as the Soyuz T9 ferry was exceeding its 115-day lifetime, according to the rumours, which created sensational press stories.

The flight continued, and a Progress ferry craft was launched to Salyut, on 21 October, carrying new solar panels, fuel and equipment. It also provided a means of propulsion for the crippled station. The crew even made two spacewalks on 1 and 3 November, lasting 2 hours 50 minutes and 2 hours 55 minutes respectively, to erect new solar panels, while cosmonauts Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov carried out a simulated EVA at the same time in the neutral buoyancy tank at Star City. The two cosmonauts on Salyut had not trained to perform such complicated EVAs and struggled to complete the tasks, as reflected in the durations of each spacewalk. The tasks had originally been planned to be completed during one EVA, but were spread over two EVAs due to the cosmonauts’ inexperience. First-time space explorer Alexandrov was amazed by the whole experience of EVA and at one point casually discarded a small unwanted item into space to see what happened. This earned him a rebuke from Mission Control, who feared confusing the station’s stellar orientation system into “thinking” that the light refection from the object might be a star. Progress separated on 13 November and the so-called doomed cosmonauts made an unheralded landing on 23 November, at T + 149 days 10 hours 46 minutes. Maximum altitude reached in the 51.6° orbit was 354 km (220 miles). The unexpected extension to the mission had gave rise to concerns over the reliability of Soyuz T in supporting a crew after such a long time in space. Soyuz T9 proved such fears were unfounded, however, and the recovery occurred without incident, giving great confidence for longer Soyuz T-supported station residences.

Milestones

92nd manned space flight

54th Soviet manned space flight

47th manned Soyuz space flight

8th manned Soyuz T space flight

7th Soviet and 23rd flight with EVA operations

Lyakhov celebrates his 42nd birthday in space (20 July)

STS 61-A |

|

Int. Designation |

1985-104A |

|

Launched |

30 October 1985 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

6 November 1985 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 17, Edwards Air Force Base, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-099 Challenger/ET-24/SRB BI-022/SSME #1 2023; |

|

#2 2020; #3 2021 |

|

|

Duration |

7 days 0 hrs 44 min 53 sec |

|

Callsign |

Challenger |

|

Objective |

Spacelab D1 research programme |

Flight Crew

HARTSFIELD, Henry Warren “Hank”, 51, USAF, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-4 (1982); STS 41-D (1984)

NAGEL, Steven Ray, 39, USAF, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS 51-D (1985)

DUNBAR, Bonnie Jean, 36, civilian, mission specialist 1

BUCHLI, James Frederick, 40, USMC, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission

Previous mission: STS 51-C (1985)

BLUFORD, Guion Stewart, 41, USAF, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-8 (1983)

MESSERSCHMID, Ernst Willi, civilian, payload specialist 1 FURRER, Reinhard, 44, civilian, payload specialist 2 OCKELS, Wubbo, 39, civilian, payload specialist 3

Flight Log

The STS 61-A mission carrying a Spacelab Long Module was chartered by West Germany for $175 million, contributing most of the 76 scientific experiments and two payload specialists – who preferred to be called payload scientists – to the seven-day expedition. The first flight by eight crew members included five NASA astronauts, two Germans and the first space-flying Dutchman, Wubbo Ockels. Pilot Steve Nagel, former mission specialist of 51-G, was flying again after only 128 days since his previous mission, a record turnaround. The Spacelab experiment operations were controlled by the West German DFVLR centre, near Munich, via the TDRS 1 and Intelsat satellites. Lift-off came at 12:00 hrs from Pad 39A and Challenger rolled on to its launch azimuth in dramatic fashion, heading towards its 57° inclination orbit, which would have a highest point of 288 km (179 miles).

A few technical problems, including communications, RCS thruster and fuel cell anomalies, delayed the entry into Spacelab by over three hours, but soon a 24-hour

|

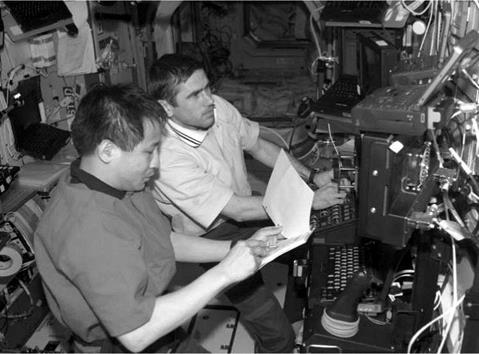

Payload Specialist Reinhard Furrer participates in medical experiments during Spacelab D1 |

round-the-clock regime of experimental work began, with the crew split into two shifts. They were aided when required by commander Hank Hartsfield and payload specialist Ockels, who overworked early in the mission and was ordered to rest. A unique experiment was the Space Sled, which was designed to investigate the reactions and adaptation of the human balance and orientation functions. It was moved backwards and forwards along a 7 m (23 ft) long track in the module. The Spacelab D1 programme included experiments in basic and applied microgravity research in materials science, life sciences and technology, communications and navigation.

Another first was achieved at the end of the 7 day 0 hour 44 minute 51 second mission, on runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base, when Hartsfield conducted a computer-controlled nosewheel steering test, deliberately steering up to 10 m (33 ft) off the centre line, to gain data on ways of eliminating excessive brake and tyre wear, such as that suffered by Discovery at the end of the 51-D Kennedy landing the previous April. The Spacelab D1 mission was considered a great success, so much so that West Germany booked a repeat mission for five years time (which actually flew eight years later).

Milestones

112th manned space flight

53rd US manned space flight

22nd Shuttle flight

9th flight of Challenger

3rd Spacelab Long Module mission

1st flight with eight crew members

1st flight by a Dutchman

1st commercially leased manned space flight

1st flight by two West Germans

1st US flight to be controlled outside the USA

STS-35 |

STS-52 |

|

Int. Designation |

1992-071A |

|

Launched |

22 October 1992 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39B, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

1 November 1992 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 33, Shuttle Landing Facility, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-102 Columbia/ET-55/SRB BI-054/SSME #1 2030; #2 2015; #3 2034 |

|

Duration |

9 days 20hrs 56 min 13 sec |

|

Call sign |

Columbia |

|

Objective |

Deployment of Laser Geodynamic Satellite II (LAGEOS II) and operation of US Microgravity Payload 1 (USMP-1) |

Flight Crew

WETHERBEE, James D., 39, USN, commander, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-32 (1990)

BAKER, Michael A., 38, USN, pilot, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-43 (1991)

VEACH, Lacy, 49, civilian, mission specialist 1, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-39 (1991)

SHEPHERD, William Michael, 43, USN, mission specialist 2, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-27 (1988); STS-41 (1990)

JERNIGAN, Tamara E., 32, civilian, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-40 (1991)

MACLEAN, Steven Glenwood, 37, civilian, Canadian payload specialist 1

Flight Log

The original mid-October launch date for STS-52 slipped when it was decided to exchange No. 3 SSME over concerns about possible cracks in the LH coolant manifold on the engine nozzle. The revised launch on 22 October was delayed by two hours due to crosswinds at the Shuttle Landing Facility, violating the Return-To – Launch-Site criteria. There were also heavy clouds at the Banjul trans-oceanic abort landing site. Despite concerns about the weather, the decision was made to proceed with the launch, in spite of higher than permitted wind speeds at launch. This caused some controversy at the time, but NASA stated that they felt the launch was safe and was performed within the intent of the rule.

Once in orbit, the crew activated the USMP-1 payload, which contained three experiments mounted on two MPESS structures in the payload bay. The Lambda Point Experiment studied the properties of liquid helium in microgravity, while the

|

|

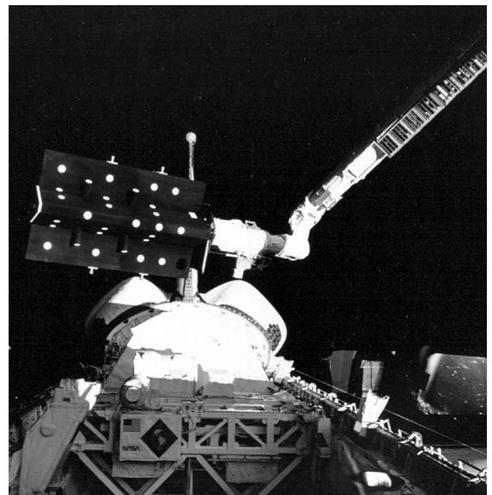

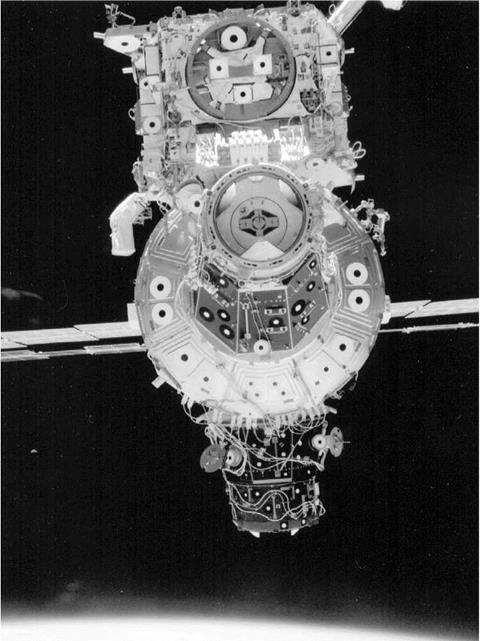

The Space Vision System (SVS) experiment is seen in the grasp of the RMS above the payload bay. Target spots placed on the Canadian Target Assembly (CTA) satellite were photographed and monitored as the arm moved around the payload bay holding the satellite. Computers measured the changing position of the dot pattern and provided real-time TV display of location and orientation of the CTA. This was an evaluation to aide future RMS operations in guiding the RMS more precisely during berthing and deployment activities

French Space Agency (CNES) and French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA)- sponsored Material pour L’Etude des Phenomenes Interessant la Solidification sur Terre et en Orbite (MEPHISTO) included crystal growth experiments. The Space Acceleration Measurement System (SAMS) had flown on previous Shuttle missions to measure and record accelerations which could affect onboard experiments. Located in the payload bay of the orbiter and operated by ground-based science teams independently of the flight crew, these experiments were a “dress rehearsal” for telescience operations on space station and other free-flying satellites.

The LAGEOS II satellite was successfully deployed at the end of FD 1 by spin stabilisation. Two subsequent firings of the solid rocket stages placed the geodynamics satellite in its 5,900 km orbit inclined at 52° to the equator. The previous satellite, LAGEOS I, which had been launched on a Delta expendable launch vehicle in 1976, was located at 110° inclination. The 426 laser reflectors on LAGEOS II provided accurate mapping of the Earth’s surface by using ground-based laser ranging systems and ground-based tracking stations worldwide. The possible applications for data collected by LAGEOS included calculations of the shifting of crustal plates, as well as rotation rates, tides and polar motion of the Earth. This data was also beneficial for global monitoring of regional fault movements in earthquake-prone areas of the Earth. By having two satellites in orbit, the data could be cross-referenced for confirmation and greater accuracy. The satellite was a joint project between NASA and the Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI), the Italian Space Agency. The upper stage used for deployment of the satellite was the Italian Research Interim Stage (IRIS), also built by ASI and being evaluated on this flight for the first time for potential use on future Shuttle missions as an operational upper stage.

Canadian PS MacLean was responsible for the Canadian Experiments-2 (CANEX-2) programme of seven experiments, located both in the cargo bay and on the mid-deck of Columbia. His programme continued and expanded upon the work begun by Canadian astronauts aboard STS 41-G (Garneau) and STS-42 (Bondar), as part of Canadian involvement in Shuttle and Space Station operations. The primary experiment in the CANEX-2 package was the Space Vision System (SVS), in which a computerised “eye’’ would assist an astronaut in operating the RMS in situations where light or field of vision was restricted. The remaining CANEX-2 experiments included research into materials exposure (sample plates attached to the Canadian-built RMS), liquid-metal diffusion, phase partitioning in liquids, measurements of the Sun, photo-spectrometer in the atmosphere, the orbiter glow phenomena and space adaptation tests and observations.

The crew also worked with a number of mid-deck and payload bay secondary experiments, including the ESA-supplied ASP, a three-independent-sensor package that was designed to determine spacecraft orientation. There was also an experiment to control pressure in cryogenic fuel tanks in low gravity (which would have application to Space Station and long-duration space systems operations), protein crystal growth experiments, fluid mixing in microgravity, heat pipe performance in space, an experiment to study the proprietary protein molecule on twelve rodents, and an investigation into Shuttle RCS plume burn contamination.

One of the more challenging aspects of this mission regarding the payload was whether the capability of the Shuttle was being fully utilised on this flight. Commander Wetherbee commented from space that the experiment package his crew were dealing with was imposing time and power constraints on the mission, and that the crew were having a tough time staying out of each other’s way while performing the mid-deck experiments. That the mission was so successful was made possible by very good pre-flight planning of both crew and experiment time.

Milestones

155th manned space flight

81st US manned space flight

51st Shuttle mission

13th flight of Columbia

1st flight of USMP payload

1st flight of Italian IRIS upper stage on Shuttle

Baker celebrates his 39th birthday in space (27 Oct)

STS-68 |

|

Int. Designation |

1994-062A |

|

Launched |

30 September 1994 |

|

Launch Site |

Pad 39A, Kennedy Space Center, Florida |

|

Landed |

11 October 1994 |

|

Landing Site |

Runway 22, Edwards AFB, California |

|

Launch Vehicle |

OV-105 Endeavour/ET-65/SRB BI-067; SSME #1 2028; #2 2033; #3 2026 |

|

Duration |

11 days 5 hrs 46 min 8 sec |

|

Call sign |

Endeavour |

|

Objective |

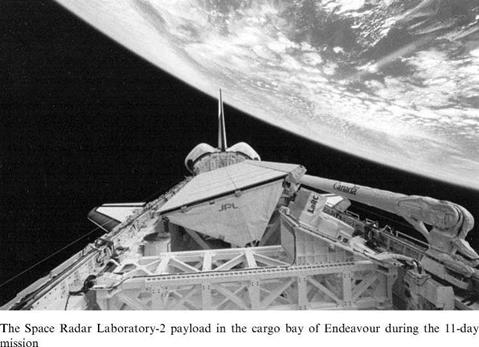

Operation of the Space Radar Laboratory (SRL)-2 in the payload bay |

Flight Crew

BAKER, Michael Allen, 40, USN, commander, 3rd mission Previous missions: STS-43 (1991); STS-52 (1992)

WILCUTT, Terrence Wade, 44, USMC, pilot SMITH, Steven Lee, 35, civilian, mission specialist 1 BURSCH, Daniel Wheeler, 37, USN, mission specialist 2, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-51 (1993)

WISOFF, Peter Jeffrey Karl, 36, civilian, mission specialist 3, 2nd mission Previous mission: STS-57 (1993)

JONES, Thomas David, 39, civilian, mission specialist 4, payload commander, 2nd mission

Previous mission: STS-59 (1994)

Flight Log

After the success of SRL-1, it was hoped that the second mission in the series would be equally rewarding. In order to ensure a smooth (and shorter) flow between the missions, it was decided to place the payload in the same orbiter (Endeavour) and to assign MS Tom Jones from the STS-59 crew as payload commander for STS-68. Endeavour returned from Edwards on 2 May and the SRL payload was removed from the vehicle in the Orbiter Processing Facility on 8 May for inspection, cleaning and maintenance. It was returned to the payload bay on 21 June and by 27 July, Endeavour was back on the pad, ready to support a planned 18 August launch. That attempt was scrubbed at T — 1.9 seconds, when the orbiter’s computers shut down the three SSMEs after they had detected unacceptably high discharge temperatures in the high-pressure oxidiser turbine for SSME #3. This required a return to the VAB to replace all three engines. The launch was rescheduled for 30 September.

|

|

Following the format of SRL-1, the crew of STS-68, working a single-shift system, soon settled down to operate their main payload and host of other mid-deck and secondary experiments once on orbit. The same 400 sites and 19 “super-sites” were targeted as on SRL-1 to provide comparison data during a different season. Unfortunately, there would be no SRL-3 mission to provide a third set of data from a different time of the year (December or January). In addition to the programme’s scheduled activities, the crew took the opportunity to record other images and impressions of Earth’s weather and environmental conditions, including the eruption of the Kliuchevskoi volcano in Kamchatka. They also studied fires in British Columbia, Canada (which had been set for forest management purposes) and used the MAPS equipment to take readings to better understand the carbon monoxide emissions from burning fires.

As well as flying over the same places as on the STS-59 mission (at one point flying the Endeavour just nine metres from where it had flown the previous April), by making small changes to their orbit, the STS-68 crew could take images of areas they had flown over just 24 or 48 hours previously. These interferometric passes were made over central North America, the Amazonian rain forests of Brazil in South America, and the volcanoes in the Kamchatka peninsula in Russia. Images like these taken over long periods of time could provide important data on the movements of the Earth’s surface – of even a few centimetres – that could be invaluable in detecting the preemptive changes in volcanoes or movements in major fault lines prior to earthquakes.

One of the radar observations was of a man-made phenomenon, a deliberate and controlled spillage of oil in the North Sea. This was designed to see if the radar could determine the difference between oil spills and naturally produced fish and plankton oils. Four hundred litres of diesel oil and 100 litres of algae-produced natural oil were dumped into the water for comparison. After the data was collected, it took just two hours for the stand-by recovery vessels to clean up the spillages.

After a one-day extension to the mission, STS-68 was diverted to Edwards from KSC because of bad weather in the vicinity of the Cape. Post-flight evaluation of the mission revealed that there had been 923 attempted data sweeps, of which 910 were successful (98.59%). Of the 292 “super-site” data-gathering attempts, the crew achieved 289 takes (98.97%) and from the 724 X-SAR attempts, 719 were acquired (99.31%). The volume of data collected equated to approximately 25,000 encyclopaedic volumes worth. STS-68 had gathered data from 83 million km2, or about nine per cent of the total Earth surface. Though SRL-3 was not flown, the data from the first two missions would help in planning the SRTM mission flown in 2000.

Milestones

173rd manned space flight

95th US manned space flight

65th Shuttle mission

7th flight of Endeavour

2nd flight of SRL payload combination

October 2003

October 2003