Initially dubbed ‘Project Astronaut’ – a term later dropped because it placed too much emphasis on ‘the man’, rather than ‘the mission’ – the effort and its search for volunteers was carried out under the auspices of the newly-founded National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), a government body established by President Dwight Eisenhower in the autumn of 1958. It represented the combined parts of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which, since 1915, had employed thousands of personnel at several research centres across the United States to design newer, better and faster aircraft. These included the Bell – built X-1 vehicle, in which Chuck Yeager first broke the sound barrier in 1947. However, in addition to taking NACA’s old resources, the new NASA also assumed control of the United States Army’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, and absorbed its ongoing aeronautical, rocketry and man-in-space projects.

Proposals for a civilian agency of this type had been made in the summer of 1957, during the International Geophysical Year, and led to a formal report, submitted to James Killian, chair of Eisenhower’s Science Advisory Council, that December. At around the same time, NACA Director Hugh Dryden, responding to the Soviet launch of Sputnik 1, also felt that ‘‘an energetic programme of research and development for the conquest of space’’ was acutely needed. In March 1958, Killian added weight to the proposal and suggested that a new agency should be based on a “strengthened and redesignated NACA’’, utilising all of its 7,500 employees, $300 million-worth of research assets and $100 million annual budget, ‘‘with a minimum of delay’’. Later that same month, Eisenhower outlined his administration’s future aims in space: to explore, to support national defences, to bolster the United States’ prestige and to advance scientific achievement. Future projects would begin with preliminary experiments, followed by automated exploration, then limited manned missions, robotic planetary flights and, eventually, journeys to the Moon and Mars.

A civilian space agency had already won the support of Eisenhower, who distrusted the significant role that the military was playing in space affairs, and the bill for its creation was quickly pushed through Congress, thanks to the efforts of Senator Lyndon Johnson. Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act on 29 July 1958 and NASA officially came into being on the first day of October, headquartered at the Dolley Madison House until better facilities could be found. Its first administrator, Keith Glennan, was a former Case Western University president, and one of his earliest official tasks, on 17 December, was to announce America’s man-in-space effort to the nation and publicly give it a name: ‘Project Mercury’. Designed by NACA aerodynamicist Max Faget, the spacecraft would employ a truncated cone, sitting on a dish-shaped heat shield, to be launched on either a suborbital trajectory atop a Redstone missile or an orbital flight aboard an Atlas rocket. Project Mercury, however, was not the only man-in-space effort: for at least two years beforehand, the military had harboured its own plans. One of the most prominent of these, cultivated by the United States Air Force, was dubbed, somewhat unimaginatively, ‘Man In Space Soonest’ (MISS).

In July 1957, the Air Force’s Scientific Advisory Committee arranged through the Los Angeles-based Rand Corporation to hold a two-day conference to discuss state – of-the-art space projects. Six months later, in the wake of Sputnik 1, a panel of scientists led by Edward Teller concluded that there was no technical reason why the Air Force could not launch a man into space within two years and an abbreviated plan was set in motion to explore the feasibility of placing a vehicle into orbit atop a converted Atlas. Contracts to build mockups of the spacecraft were awarded to North American Aviation and General Electric in March 1958 and, with a sense of great urgency, plans were implemented for an effort initially called ‘Man In Space’, then, from June, an accelerated ‘Man In Space Soonest’.

Animal-carrying flights, read the proposal, would be attempted in 1959, followed by a manned mission in October I960 and lunar landings as early as 1964. The five – year project would cost $1.5 billion. MISS, a ballistic capsule measuring 1.8 m in diameter and about 2.4 m long, would be fully automated and capable of supporting a single astronaut for up to 48 hours in orbit. Interestingly, the astronaut would lie supine in a contoured couch which could be rotated according to the direction of the G forces building up during ascent and re-entry.

Two camps existed over which missile – Atlas or Thor – should be used to loft the MISS spacecraft into orbit; the former was considered too unreliable and, moreover, would subject its astronaut to around 20 G, beyond the limits of human tolerance, in an abort situation. A two-stage Atlas, on the other hand, could provide a shallower re-entry flight path and reduce this to a survivable 12 G, but others expressed preference for a modified Thor intermediate-range ballistic missile, fitted with a Nomad fluorine-hydrazine upper stage. Eventually, on 2 May 1958, detailed designs for the MISS spacecraft, its operational procedures and the decision to employ the

Thor missile, were forwarded to Air Force Headquarters, with a first manned launch tentatively scheduled for October I960.

However, it was felt in many quarters that development of the Thor-Nomad would take longer than planned, perhaps requiring 30 test launches and causing massive cost overruns. Consequently, the Air Force’s undersecretary was convinced that using a modified Atlas as the launch vehicle could cut the project costs below the $100 million mark. Unfortunately, this would also mean cutting the orbital altitude achievable by MISS from 275 km to just 185 km, essentially putting it out of range of the tracking network for much of its flight. Still, on 15 June 1958, the Atlas was brought on board, the project’s budget descended to $99.3 million and the first manned launch was targeted for April 1960.

Ten days later, the Air Force selected test pilots Robert Walker, Scott Crossfield, Robert Rushworth, William Bridgeman, Alvin White, Iven Kincheloe, Robert White, Jack McKay and – notably – Neil Armstrong as candidates to fly the MISS spacecraft. Arriving on the scene ten months before the Mercury Seven and almost two years before the first Soviet cosmonaut team was chosen they represented the first ‘astronaut’ selection in history. These astronauts would have been little more than passengers, inspiring the denigration of Chuck Yeager and others that the early space fliers were ‘spam in a can’, riding relatively simple ballistic capsules and parachuting to a water landing in the vicinity of the Bahamas.

Within weeks, however, Eisenhower’s plan to create a civilian space agency had developed into legislation and Brigadier-General Homer Boushey of Air Force Headquarters announced that the Bureau of the Budget was blocking the further release of funds for MISS. A chance remained to make the project a reality if its costs could be kept below an impossible $50 million ceiling in 1959, although this would have pushed the first mission into the spring of 1962. Eisenhower’s ingrained distrust of military involvement in the human spaceflight effort, coupled with the fact that the soon-to-be-formed NASA would not be spending more than $40 million on its own man-in-space project for 1959, signalled the final death-knell for MISS. By the third week of August 1958, Eisenhower assigned NASA specific responsibility for developing and carrying out manned space missions and $53.8 million, set aside for Air Force projects, including MISS, was transferred from the Department of Defense to the civilian agency. It has been speculated that, had it gone ahead with the required level of funding, it is quite possible that MISS would have beaten the Soviets into space, orbiting a man sometime in 1960.

At around the same time, the Army was planning its own, simpler, man-in-space effort, initially called ‘Man Very High’ (with Air Force participation, utilising the Manhigh gondola design) and, later, ‘Project Adam’. This had been the brainchild of Wernher von Braun, designer of the V-2 missile and among a handful of German rocketry experts brought to the United States in the wake of the Second World War. Had it gone ahead, its proponents claimed, it would have reached space even ‘sooner’ than the Soonest. Utilising a converted Redstone missile, it would have placed a capsule onto a ballistic, suborbital trajectory, probably similar to that followed by the first two manned Mercury missions. The Army’s astronaut would have been housed inside an ejectable cylinder, 1.2 m wide and 1.8 m long, which itself would have been encased inside the Redstone’s nosecone. The rather tongue-incheek justification for the project was as a step towards improving techniques of troop transportation, although Hugh Dryden scornfully remarked that “tossing a man up in the air and letting him come back. . . is about the same technical value as the circus stunt of shooting a young lady from a cannon’’. By July 1958, the Army was told that Project Adam’s impracticability meant that it would not receive its requested $12 million of funding.

Meanwhile, the Navy, not to be outdone, proposed its own Manned Earth Reconnaissance (MER) initiative. This would have taken the form of a cylindrical spacecraft with a sphere at each end. After launch atop a two-stage booster, the spherical ends of the vehicle would expand laterally along two structural, telescoping beams to form a delta-winged, inflated glider with a rigid nose. The astronaut would then be able to make a controlled re-entry and water landing. Several studies were undertaken, including one jointly between Convair and the Goodyear Aircraft Corporation. By the time the partnership made its report, in December 1958, Project Mercury was already well underway. Although MER was undoubtedly the most ambitious of these early projects, its emphasis on new hardware and cutting-edge techniques led many observers to doubt its chances of approval, with or without the advance of Mercury. Indeed, of all of the military plans, MISS probably came closest to fruition, before the clear direction was taken to place manned spaceflight in the hands of a civilian organisation.

The urgency with which NASA addressed the need to launch an astronaut was heightened by the fact that, within four months of Glennan’s announcement, the Mercury Seven were in place. ft was already known that the Soviet lead on space achievement was strong and that they were surely planning their own man-in-space effort, with I960 or shortly thereafter considered the most likely timeframe for a human launch. fndeed, Time magazine told its readers in September of that year that the long-awaited Soviet shot “could happen tomorrow’’, adding that “few of the world’s scientists doubted. . . that man at last was nearly ready to launch himself boldly and bodily into space’’. Eighteen bold bodies survived the punishing tests at Lovelace and Wright-Patterson and their names were forwarded to a NASA selection committee, with the original intent to choose six astronauts. However, after firmly picking five names, officials and physicians could not agree between two competing volunteers and ended up selecting both of them.

fn many ways, the Mercury Seven were quite distinct from their counterparts in the Soviet cosmonaut team. For a start, their ages were somewhat higher. According to Neal Thompson, in his 2004 biography of Al Shepard, NASA had opted for “steely, technology-savvy test pilots’’, who were “mature… who’d been around, been tested and stuck it out’’, rather than inexperienced, wet-behind-the-ears young bloods for whom the fascination might lose its lustre when faced with the prospect of long hours and extremely hard work. As a result, Glennan’s agency stipulated that the astronauts had to be 25-40 years old at the time of selection, around 1.8 m tall and no heavier than 80 kg, to ensure that they could fit comfortably inside the tiny, conical Mercury capsule. They were also required to possess degrees in medicine, physical science or engineering, together with several years of professional expertise, including test piloting credentials, and at least 1,500 hours in their flight logbooks. Interestingly, this eliminated some of the most famous names in American experimental aviation – Chuck Yeager did not hold the required academic qualifications and Scott Crossfield, the first man to fly at twice the speed of sound, was a civilian – although the former at least would publicly ridicule Project Mercury, believing that it did not require the talents or merits of a test pilot.

The choice of combat and test pilots seemed logical, but had actually come about after lengthy debate: submariners, high-altitude balloonists and even mountaineers were considered in the early days and original plans advocated a public call for volunteers, after which perhaps 150 might be chosen for testing and around a dozen finally selected. In fact, a notice to this effect, with an annual salary of between $8,330 and $12,770, had appeared in the Federal Register on 9 December 1958. Nowadays, of course, astronauts are chosen from both the military and civilian sectors, but the sheer unknowns surrounding space travel at the close of the Fifties prompted the selection committee and, in particular, Navy psychologist Bob Voas, to favour test fliers from the armed forces. It also did not hurt, wrote Deke Slayton, that “you wouldn’t have to be negotiating salaries with active-duty officers who volunteered”. Moreover, none of the Mercury Seven was obliged to resign their military commissions in order to work for a civilian agency and, indeed, continued Slayton, given the state of NASA in late 1958, “you’d have had to be an idiot to give up your Air Force or Navy career to join them’’. For his part, President Eisenhower heartily endorsed the idea of selecting purely from the military, effectively ending the national call for volunteers.

“The astronaut training programme,’’ Glennan told the Dolley Madison audience that April afternoon in 1959, “will last probably two years. During this time, our urgent goal is to subject these gentlemen to every stress, each unusual environment they will experience in that flight.’’ That training programme had scarcely begun and according to Chris Kraft, a legendary NASA flight director from those early days, “we were inundated with the newness of everything”. The astronauts expected their preparation to include many hours in the cockpits of jet aircraft – “we didn’t know what else to train on,’’ Gordo Cooper remarked – but their actual training for one of the most audacious feats in human history would encompass much more: physical and psychological conditioning, together with intense, PhD-level technical, scientific and medical instruction, to enable them to understand the intricacies of the spacecraft and rockets upon which their lives would depend. Spaceflight training had never been attempted and, in many ways, NASA and its first seven astronauts were forced to make it up as they went along. Indeed, Bob Gilruth, head of the Space Task Group, which included Project Mercury, stressed that they were not merely ‘hired guns’ and that, unlike the military, “where direction comes from the top’’, their direct input with respect to spacecraft design was expected and desired.

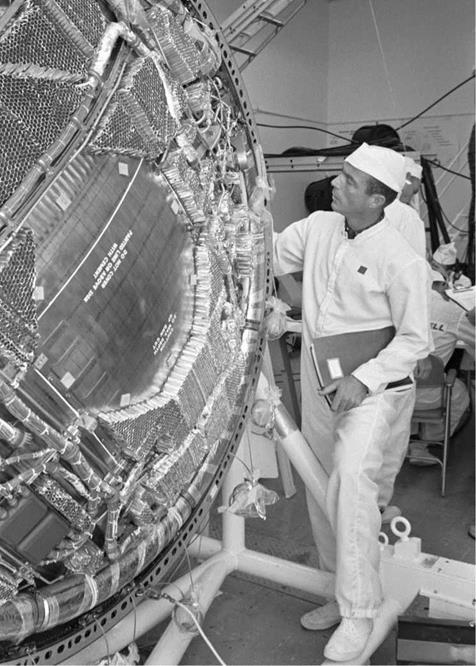

One particular training contraption, known as the Multiple-Axis Space Test Inertia Facility (MASTIF), was used to simulate the motions of the Mercury capsule in orbital flight conditions. Located at the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, it comprised a system of three interlocking concentric ‘cages’, one inside the next, with the innermost resembling the spacecraft itself. The cages could be

Described as one of the most sadistic trainers ever created, the Multiple-Axis Space Test Inertia Facility (MASTIF) comprised three interlocking cages to simulate motions about roll, pitch and yaw axes.

programmed to spin, sometimes simultaneously, about all three axes – roll, pitch and yaw – at up to 30 revolutions per minute. Nitrogen-gas jets attached to the cages created these motions, which were intended to precisely mimic the worse-than-worst – case scenario of a complete loss of control of the capsule whilst in space. As the simulator tumbled, the astronaut, with all but his arms held firmly in place, had to read eye-level instruments and actuate the jets by means of a control stick to somehow interpret the motions and correct and steady the capsule accordingly. For three weeks in February and March I960, all seven Mercury astronauts were wrung through the MASTIF, which often left them nauseous and vomiting and which all would agree was one of the most sadistic trainers they had ever ridden.

Elsewhere, punishing centrifuge runs at the Naval Air Development Center in Johnsville, Pennsylvania, subjected their bodies to forces as high as 16 G – enough to smooth back the skin on their faces and break blood vessels in their backs – in recognition of the fact that so little was known about deceleration during descent. Nicknamed, rather innocuously, ‘the wheel’, the centrifuge “took every bit of strength and technique you could muster to retain consciousness,” according to John Glenn. These exercises were perverted yet further by so-called ‘eyeballs-in, eyeballs – out’ testing, where the forces were extended by simulating another worse-than-worst – case eventuality that the Mercury capsule could splashdown in the sea on its nose, rather than its base; the astronauts were rotated 180 degrees and thrown violently against their restraining straps, which Al Shepard sarcastically called ‘‘a real pleasure’’. Indeed, one NASA physician who underwent the test could not properly catch his breath for some time afterwards. It later became clear that his heart had slammed into one of his lungs and deflated it. . .

The eyeballs-in, eyeballs-out testing eventually led to recommendations for more durable shoulder harnesses inside the capsules and, after their first visit to prime contractor McDonnell Aircraft Corporation’s St Louis plant in Missouri, the astronauts realised to their surprise that no window – only a blurry periscope – existed for them to see outside. Although their suggestion to include a viewing window was implemented, the first three Mercury spacecraft had already been built and outfitted, meaning that at least the first American in space would have to rely instead on two small portholes and the fisheye view transmitted through the periscope lens onto a circular screen in front of his face. The astronauts’ ability to apply their technical prowess and implement practical changes proved quite at odds with the experiences of Yuri Gagarin and his comrades, who had little or no input into the Vostok design process. In fact, with each of the Mercury Seven assigned a responsibility – Carpenter focused on communications and navigation, Cooper on Redstone rockets and trajectories, Glenn on cockpit layout, Grissom on controls, Schirra on environmental systems and space suits, Shepard on recovery equipment and Slayton on the Atlas booster – questions of whether to include aircraft-like rudder pedals or a control stick, whether to use gauges or easier-to-read tape-line instruments, where to position certain switches or handles to make them easily reachable or how best to remove the capsule’s hatch in an emergency were encountered on a regular basis.

In spite of the intense preparation, some psychologists remained fearful that the two-year wait for the first manned mission could lead to ‘over-training’ and staleness, although Shepard and others would strongly disagree and remark that the similarity of training with actual flight conditions was a key factor in making the real thing feel ‘routine’. The choice of Shepard as the first American in space was delivered on 19 January 1961 – the eve of John Kennedy’s presidential inauguration – when Bob Gilruth personally visited the astronauts at their headquarters at Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. After 20 months of training, it did not come as a great surprise. Gilruth had already asked them, weeks earlier, to write the name of the astronaut, excepting themselves, that they would like to fly first. ‘‘We all intuitively felt that Bob had to make a decision as to who was going to make the first flight,’’ Shepard said, ‘‘and when we received word that Bob wanted to see us at five o’clock in the afternoon in our office, we sort of felt that perhaps he had decided.’’

Gilruth wasted little time and got straight to the point. Revealing that it was the hardest decision he had ever made, he announced that Shepard would fly first, Gus Grissom would fly second and John Glenn would support both missions. Years later, strong suspicions would abound that the choice of naval aviator Shepard had much to do with President Kennedy’s own nautical background and more than one member of the Mercury Seven would attribute the decision purely to politics. Indeed, even the Shepard-Grissom-Glenn trinity neatly represented the United States Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. (Army pilots had not been selected, on the basis that they lacked the required expertise in high-performance jets.)

No further public decisions on subsequent missions would be made, Gilruth told them, and, in fact, the three men’s names as mere ‘candidates’ for the first flight would not be announced to the world for another five weeks. Shepard’s selection as America’s first astronaut would not be revealed publicly until 2 May, as his first launch attempt was in the process of being scrubbed. Until then, the trio had to run through their own training facade of ‘not knowing’ which of them was to fly – ‘‘a ruse,’’ wrote Neal Thompson, ‘‘that all the astronauts thought was ridiculous and annoying’’. Oblivious, the media’s favourite had always been John Glenn, whose appearance, eloquence and warm demeanour typified the ‘all-American’ hero, and much surprise abounded when he, in fact, was not picked. Some newspapers even implied that inter-service rivalry was so strong that the Air Force may have deliberately leaked Glenn’s name to embarrass NASA and reduce his chances. Others supported Grissom, since his parent service – the Air Force – was already in the process of developing its own winged spacecraft called ‘Dyna-Soar’, together with an Earth-circling space station.

Glenn was the first to offer his hand to Shepard in congratulation, but others, including Wally Schirra, were ‘‘really deflated’’ by the decision. Deke Slayton, although he had privately ranked Shepard as the best in terms of piloting skills and general ‘smartness’, felt humiliated and could scarcely believe that he had not even made the cut of the final three. Gilruth’s choice did not surprise Scott Carpenter, though, who had been aware for two years that Shepard was ‘‘single-minded in his pursuit of the first flight’’. Moreover, according to Walt Williams, NASA’s director of operations for Project Mercury, Glenn’s image-consciousness, his untiring effort to perfect his ‘boy-next-door’ image and his currying of favour with top brass, led some officials to consider Shepard the best. His intense focus on the mission, his desire to know every aspect of the engineering and capsule design and his superb flying skills left him the obvious choice.

Admittedly, all seven knew that only one of them could make the coveted first flight, even though it would amount to little more than a 15-minute suborbital lob into the heavens atop a converted Redstone, but the disappointment was tangible. ‘‘I think Life magazine got into the act with some horseshit about the Gold Team (Glenn, Grissom and Shepard) and Red Team (the rest of us),’’ wrote Deke Slayton, ‘‘and I even had to have a press conference. . . a couple of days after the announcement to reassure everybody that we weren’t depressed.’’ In a situation once described as seven pilots all trying to fly the same aircraft, each man had been chosen at the very pinnacle of his profession; each was hyper-competitive and in their time together each had set himself the personal goal of ensuring that ‘the other guy’ never got so much as half a step ahead in ‘the game’. That game, and that intense competitiveness, ran from flying jets to mastering the MASTIF to winning a dispute over an aspect of Mercury design to racing the fastest in their flashy sports cars.

With the exception that all were military pilots and all would someday be flying into space, little commonality existed between them and their Soviet counterparts. The former were screened from the world and venerated only after their missions. The Mercury Seven, on the other hand, were placed on a pedestal of hero-worship from the day of their selection. They were, in a sense, ‘premature heroes’, with their personal stories sold by their lawyer Leo D’Orsey to Life magazine for $500,000 and a variety of perks – from sleek Corvettes on one-dollar-a-year leases from General Motors to the choicest picks of real estate – headed their way. They would battle the evil Soviet empire, take democracy to the new ‘high ground’ of space, and Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr, it was hoped, would be the first man to do it.