ALL ABOARD THE ‘MOLLY BROWN’

Only days after Gemini 2’s splashdown, Charles Mathews revealed that late March seemed the most achievable target to launch Gus Grissom and John Young on the first manned mission. The two men and their backups, Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford, had been training since mid-April 1964; indeed, wrote Stafford, they ‘‘became virtual citizens of St Louis, Missouri. . . flying in on Sunday night or Monday morning in our T-33s and T-38s, spending days at the McDonnell plant at Lambert Field then going back to Houston on Thursday or Friday’’. At St Louis was the Gemini mission simulator, which provided them with the sights, sounds and vibrations that they could expect on a real flight; moreover, it was adaptable for each crew, whose objectives would differ markedly. Grissom, an Air Force officer promoted from captain to major in July 1962, would become the first man to be launched into space twice. He had been one of the earliest astronauts assigned to

|

|

Project Gemini and the spacecraft reflected, among other things, his short stature. Whereas Grissom, at 1.6 m, could comfortably fit the cockpit, the taller Stafford “was jammed in, especially when I had to wear a pressure suit and helmet”.

For Stafford and fellow ‘tall’ astronaut Jim McDivitt, this posed a figurative and literal pain in the neck. “Eventually,” wrote Stafford, ‘‘the McDonnell engineers removed some of the insulation from the inside of the hatch to create a slight bump that gave us room for our helmets’’. First fitted for Gemini VI – which Stafford flew, alongside Schirra, on the first rendezvous mission – it became known, naturally, as ‘The Stafford Bump’. Among the astronauts, Gemini had already earned itself the nickname ‘Gusmobile’, because Grissom was the only man small enough to scrunch himself into his seat and close the hatch without banging his head. The prime and backup crews spent around 35 hours apiece in the St Louis simulator in the late spring and early summer of 1964, learning its quirks and idiosyncrasies, before it was finally dismantled and shipped to MSC in Houston towards the end of July. Another, near-identical simulator was also set up at the Cape in October.

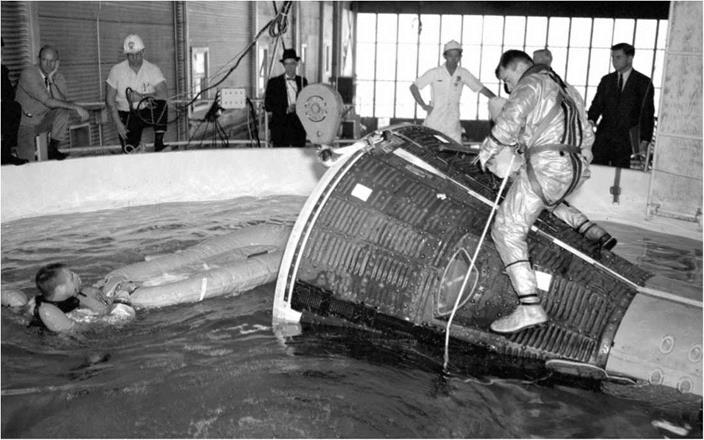

During their early months of training, the four men closely monitored the development of the ‘real’ spacecraft at St Louis, watching as it passed through various systems tests and inspections, then spending many hours in its cockpit. Elsewhere, in Dallas, Texas, they participated in exercises on a Gemini moving-base abort simulator, which projected their ascent profile in striking detail and enabled them to rehearse their responses to malfunctions. At Ellington Air Force Base, not far from MSC, they were dunked in a ‘flotation tank’ to practice getting out of a boilerplate mockup of the Gemini capsule, with and without space suits, both floating and submerged. Only weeks before launch, in February 1965, Grissom and Young rode a boat out into the Gulf of Mexico to a mockup capsule, which they had to board and run through their post-splashdown checklists, their emergency egress procedures and the opening of their one-man liferafts.

Mission planning sessions, centrifuge training at Johnsville in Pennsylvania, space suit fit checks, physical exams and preparation for the Gemini 3 experiments quickly turned their training schedule into an unending marathon. ‘‘The days just seemed to have 48 hours, the weeks 14 days and still there was never enough time,’’ Grissom would recall later. ‘‘We saw our families just enough to reassure our youngsters they still had fathers.’’ By the time the mission simulator had been set up at the recently- renamed ‘Cape Kennedy’ – the old Canaveral – in October 1964, it would become the astronauts’ second home: Grissom would put in more than 77 hours of training in it, rehearsing every phase and every minute of what would be a five-hour mission, with Young slightly eclipsing him at 85 hours. As launch day neared, Grissom had sat through 225 abort scenarios, compared to 154 for his rookie pilot. By February, when queried by journalists, Grissom confirmed that, after nine months of training, he and Young were ready to go. Indeed, even Jim Webb confidently expected a launch as soon as 15 March.

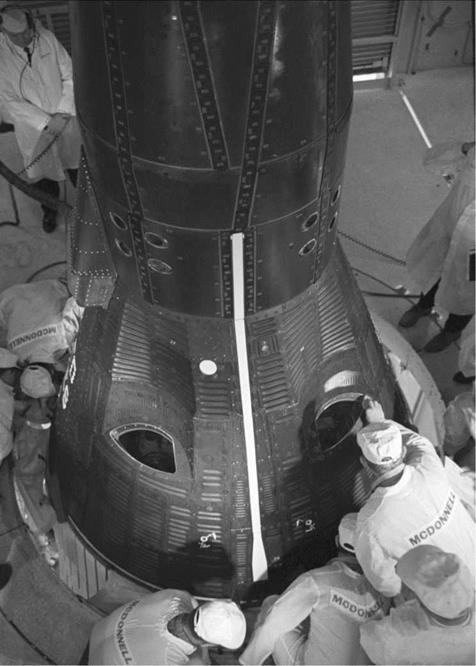

Meanwhile, the development and testing of the Gemini 3 capsule was gathering pace. Its construction had been completed in December 1963 and, following six months of engineering changes and installation of equipment, it began integrated testing in the summer. McDonnell’s ‘in-house’ testing was completed by September and on 27 December, after its own inspections and a simulated flight, NASA accepted the spacecraft for delivery. It arrived at Cape Kennedy aboard a C-124 transport aircraft on 4 January 1965 and was ready for transfer to Pad 19 early the following month. At the same time, its Titan II launch vehicle – GLV-3 – arrived in late January and was mechanically mated with Gemini 3 on 17 February.

The mission itself was too short, many felt, for any meaningful rendezvous data to be gathered. In October 1963, MSC had suggested flying the Rendezvous Evaluation Pod (REP) on Gemini 3 and releasing it into orbit to test the rendezvous radar, although this was cancelled and rescheduled for a later mission. The astronauts themselves soon got in on the act. Word leaked out in the summer of 1964 that Grissom and Young were pushing for an ‘open-ended’ flight, in effect giving them the option to decide how many orbits to fly. ‘‘Gus and John and the rest of us thought a 30-orbit flight, almost two days, was the next logical step after Gordo’s MA-9,’’ recalled Slayton, but on this occasion the astronauts’ judgements were overruled.

The limitations of the existing tracking network and worries about erring on the side of caution on Gemini’s first manned mission won the day and it remained at five hours. Even Grissom acquiesced that he felt sufficient data could be extracted from a three-orbit flight. That ‘data’ would come primarily in the form of demonstrations of the spacecraft’s manoeuvrability, using its OAMS thrusters, and a decision was made to conduct three firings to insert Gemini 3 into a ‘fail-safe’ orbit, from which it could still re-enter in the event of a retrorocket failure. In reality, Grissom and Young would fly in too low an orbit to be permanent, but the fail-safe option at least ensured that the spacecraft could return promptly and, insofar as possible, that the crew would survive.

To achieve it, the aft OAMS would be fired to separate Gemini 3 from the second stage of the Titan. This would insert the spacecraft into an elliptical path of 122-182 km, whilst a second burst about 90 minutes into the mission would slightly cut the velocity and near-circularise the orbit. Then, whilst over the Indian Ocean around two hours and 20 minutes after launch, a series of ‘out-of-plane’ burns would be conducted to thoroughly gauge the performance of the OAMS. Finally, above Hawaii on the third pass, a pre-retrofire burst would insert the spacecraft into an elliptical re-entry orbit with a perigee of just 63 km.

Scientific and technical experiments would consume a small portion of the astronauts’ time. A Panel On In-Flight Scientific Experiments (POISE) had already been established within NASA and proposed a series of investigations which would largely run themselves. Two promising candidates for Gemini 3 were those originally assigned to Al Shepard’s ill-fated MA-10 mission. One explored the combined effects of radiation and microgravity on cells, the other focused on cell growth in space. The former sought to expose human blood samples to a known quantity and quality of radiation, both within the capsule and on Earth, allowing the frequency of chromosomal aberrations in the space-flown and ground-control specimens to be compared. On Gemini 3, it was mounted on the right-hand hatch, inside a halfkilogram hermetically-sealed aluminium box. To activate it, Young had to twist a handle to commence irradiation of the blood samples.

|

A Gemini spacecraft is prepared for launch. |

The second experiment was Grissom’s responsibility and was situated inside his left-side hatch. Since it was considered easier to detect the effects of microgravity in simple cell systems than more complex organisms, it consisted of the eggs of a sea urchin. These were fertilised at the beginning of the experiment and the possible changes observed at several stages of their development. Grissom was required to turn a handle 30 minutes before launch to fertilise the eggs, then four times in flight to fix the dividing cells at specific stages of growth. Each handle turn effected by Grissom would be mirrored in a control experiment on the ground.

Additionally, a third investigation, originally envisaged for MA-10, was a re-entry communications demonstration. It had been theoretically shown that by adding fluid to ionised plasma during the period of re-entry blackout, communications could be restored by lowering the plasma’s frequency sufficiently to allow UHF transmissions to get through. The lengthy blackout during John Glenn’s fiery plunge to Earth and Scott Carpenter’s heart-stopping overshoot may have benefitted from such an experiment, despite its $500,000 price tag. It involved the fitment of a water – expulsion system, whose starter switch would be thrown by Young when the capsule descended below 90 km. Water would be automatically injected into the plasma sheath around the spacecraft in timed pulses for two and a half minutes, while ground stations monitored and recorded UHF radio reception.

Early in March 1965, a flight readiness review confirmed that, with the exception of several minor problems, Gemini 3 was ready to fly. The Titan II passed its final test on the 18th and launch was scheduled for 9:00 am on the 23rd. The countdown commenced at 2:00 am on launch morning, which dawned dull and overcast, but the decision was taken to proceed. Three hours later, Grissom and Young were awakened, sat down to the traditional low-residue breakfast of tomato juice, half a cantaloupe melon, porterhouse steaks and scrambled eggs. Young received a long good-luck telegram signed by 2,400 Orlando residents, from whose high school he had graduated years before. The two men then donned their space suits. Unlike Project Mercury, the Gemini ensembles were white, not silver, and comprised a nylon material overlaying a rubberised inner lining. The gloves were removable and were attached to rotating wrist joints, permitting full movement, and learning from the experiences of the Mercury pilots, included ‘fingertip lights’ to help read cockpit instruments.

The prime and backup crews had all spent the past several days in the new quarters at the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building, whose accommodations, wrote Ray Boomhower, ‘‘were a far cry from the ones the astronauts were used to at Hangar S in their Mercury days’’. They were comfortably furnished, quiet and even boasted a gym with exercise bicycles and punch bags. Shortly after 7:00 am on launch morning, the astronauts headed for Pad 19, where technicians inserted them into their couches in the capsule which Grissom had light-heartedly dubbed ‘Molly Brown’. The name came from the unsinkable Titanic survivor popularised in the 1960 Broadway musical and 1964 movie.

Grissom hoped, it seemed, that borrowing Brown’s name for Gemini 3 would ward off the demons of watery bad luck which had hit him at the end of his Liberty Bell 7 mission. ‘‘I’ve been accused of being more than a little sensitive about the loss

of my Liberty Bell 7,” he explained before launch, “and it struck me that the best way to squelch this idea would be to kid it.” Kidding or not, NASA officials doubted that the name conveyed the right message, but when offered either Molly Brown or Grissom’s other choice – Titanic – they quietly backed off. However, they never named it as such in official documents. In fact, at an earlier stage, Grissom had suggested the name ‘Wapasha’, after a Native American tribe from his home state of Indiana, although the risk of the media renaming it ‘The Wabash Cannonball’ meant that was also removed from the list.

Inside the spacegoing Molly Brown, a near-flawless countdown proceeded smoothly, leaving them 20 minutes ahead of schedule and giving Young reason to complain about the extra time spent lying flat on his back in his uncomfortable space suit. The overcast weather refused to lift and the clock was halted at T-30 minutes when a first-stage oxidiser line in the Titan sprang a leak. Although this problem was quickly resolved, the countdown had to be held for 24 minutes to ensure that the leak had stopped. Thankfully, by this point, the grey clouds had cleared, and at 9:24 am the Titan II took flight. ‘‘You’re on your way, Molly Brown!’’ yelled Capcom Gordo Cooper. Liftoff, the two astronauts recalled later, was so smooth that they felt nothing; their only real cues were the startup of the mission clock on Gemini 3’s instrument panel and hearing Cooper’s words. In fact, the early stages of the ride were smoother than they had experienced in the moving-base simulator in Dallas.

For the first 50 seconds, Grissom kept both hands firmly on the ring which would trigger Molly Brown’s ejection seats in the event of a booster malfunction. Young, wrote Ray Boomhower, also had such a ring on his side of the cabin, but, looking over, Grissom noted that the unflappable rookie had his hands calmly folded in his lap. ‘‘During this time,’’ Young recalled later, ‘‘we didn’t say a word to each other because there was so much to do so fast.’’

The Titan’s first stage was exhaused two and a half minutes into the climb and second-stage ignition bathed the entire cabin with a flood of eerie orange-yellow light which surprised Young. The rocket, Cooper told them, had slightly exceeded its predicted thrust and the astronauts could expect a larger-than-predicted pitchdown after second-stage ignition as it began to steer a course for orbit. Five and a half minutes after launch, the second phase of the ascent was over and, with a bark like a howitzer, pyrotechnics severed Gemini 3 from the Titan. Grissom fired Molly Brown’s aft OAMS thrusters to pull away from the booster. The Titan overperformed slightly, but Gemini 3 still ended up in a close-to-expected orbit of 122175 km. For his part, Young, who was making the first flight of what would turn into a six-mission career, was simply astounded by the sense of speed and the stunning view of Earth.