When you stop to think about it, the story line of the subject of this book would make a pretty good Hollywood blockbuster. It has at least a few of each of the ingredients – and often a generous helping of some of the tastier items – that make a box-office hit.

This narrative is an epic. It starts with the birth of one of the most exciting, most dynamic, and most important American industries – the airline industry. It spans three-quarters of a century, almost as long as the life span of air transport itself. When critical events occurred, when vital innovations were needed, the subject of this tale was invariably at center stage.

Its characters are larger than life. There was the young air mail pilot whose daring and courage had literally stunned the world. There was the swashbuckling tycoon who built it into an international powerhouse of a company and earned a fortune on top of his fortune; but was finally forced out of the business he loved. There were the airmen and women who performed unrecognized acts of accomplishment, some of them heroic, in the service of what they regarded as a true vocation, not just a job. There were movie stars, celebrities, politicians, presidents, even Popes. There were skillful and daring leaders with a vision of the future and the courage to build it, and there were financial manipulators who almost destroyed it.

It was the first at so many things. It was the first to span the continent, coast-to-coast. It claimed many technological firsts, often initiated in cooperation with the great aircraft manufacturers. As the author has observed, its contribution to launching, with Douglas, the legendary series of modern twin-engined “DC” airliners, was a turning point in air transport history. It worked with Boeing to develop a lesser-known but perhaps no less significant aircraft, the Stratoliner – the world’s first pressurized airliner. Its owner’s perfectionist insistence with Lockheed was the impetus behind the creation of the incomparable Constellation. It was the first airline to turn its back on propellers and boast of an all-jet fleet.

It, of course, is TWA, the transcontinental airline, the trans world airline, the airman’s airline, the airline of the stars, the airline of the Popes, the airline of legend. Howard Hughes, the legendary former owner of TWA, also produced silver-screen epics – but even Hughes’s best screenwriters could not have dreamed up a more exciting saga than the true story of his own airline. This world-wide corporation achieved such cosmopolitan fame that the name TWA became a household word, synonymous with “airline.” Even

though TWA’s globe-girdling days are behind it, the proud TWA name remains even today the best-known in commercial aviation throughout the world, from North America to Europe and through the Middle East to Asia.

As our airline celebrates its 75th birthday, historian Ron Davies and artist Mike Machat, aided and abetted by statistical gums John Wegg and Felix Usis (himself a TWA pilot), have brought into print a new and somewhat different look at our history. As in previous books in this Paladwr Press pictorial series, they focus on the aircraft as a way to tell the airline’s story. It’s a good way to tell the tale because, after all, the airplanes are the visible and publicly recognizable symbols of what we do. The airplanes help to define the personality of the airline and conjure up the images of airline life. Show an old airline hand a picture of an airliner, or an old route map, or even an ancient (and, by definition, rare) timetable, and the stories will flow. The book will start many of them flowing among TWA’ers, not only stories of what was, but also of what will be again.

But the story of an airline — especially this airline — is much more than one of routes and planes. It is very much about people, just as the airline business is a people business. TWA is populated by walking repositories of our history, employees who have given 20, 30, 40, or even more years to TWA. Many are veterans who carried it through 75 years, and who are now supported by younger TWA’ers, who are rebuilding it for 75 years more. Their dedication, their professionalism, and above all, their loyalty — not to mention a few of their good stories – are captured here.

Ron Davies and his Paladwr team have packed an incredible amount of information into the 112 pages of this book. They have incorporated marvelously detailed drawings, a wonderful selection of photographs (some familiar, some rare), informative maps, and meticulously compiled and detailed fleets lists and data tables. It is a wealth of information about TWA but it is nevertheless only a taste of the 75-year saga of Trans World Airlines. The first chapters are here. New chapters are being written every day. There are, and will be, many TWA stories to come. We hope that the Paladwr folks will visit us again in a decade or two to catch up.

Meanwhile. I invite you to enjoy this book, and thank you for flying TWA!

ЛЬачІ £

Vice President-Corporate Communications St. Louis, Missouri — September 2000

Air Express Airline from £J^ to

over Contract Air Лівії Route Ho. 4. ,

Time of Departure^?# Time b&fVj

Time atLas Ve5as 3;/ 0 from L. D. to <3–у*

Time ofArriiai (?■ I ^ Total Flying Time v Maximum АШІлкУ^000- Maximum Speed Airmail Car^o^lA-lbs.

Total weiahtcarrietlSLZS lbs. C/Pilot-Ship hlo._A

This is a reproduction of Mr. Ben Redman’s ticket issued by W. A.E.

It was signed by Charlie “Jimmy" James, seen as the pilot in the

picture above.

Author

Tackling the history of T. W.A. has been a formidable task, not simply to assemble 75 years of glorious history, but to do justice to the illustrious chronicle of achievements within the covers of one of Paladwr Press’s series of Great Airlines of the World. To write a 300-page or 500-page text would be easier than to fashion a concentrated narrative that would complement the 170 photographs, 48 ‘Machats’ (precision drawings), tabulations of more than 1,200 individual aircraft, 25 maps, and other illustrative features of this book. But I have endevoured to encapsulate the essentials: the ancestral anecdotes of Western Air Express and Harris Hanshue’s fight for recognition; the experimental air-rail service of T. A.T.; Jack Frye’s sponsorship of the famous Douglas twins; Howard Hughes’s dramatic initiatives—and his fall from grace; the era of the Constellations; the attainment of leadership across the Atlantic; and the erosion of size and service in more recent times. Each of these historic episodes, and others, would justify a small book. But a comprehensive coverage, with every detail, would need a bigger and more expensive volume, beyond the price range that seems reasonable for most pockets.

Many of T. W.A.’s achievements have been remarkable because they have been of inestimable benefit not just for the St. Louis airline, but for the air transport industry as a whole. The pre-war Douglas airliners that came to dominate the airways would not have been built if the T. W.A. specification for a modern airliner had not been outlined by Jack Frye in 1932. Howard Hughes’s unique combination of record-breaking flying experience and industrial acumen, together with persistence to cross technical thresholds, led to the dramatic delivery of the Constellation in 1944, a triumph both for Hughes and for T. W.A. The manufacturers, Douglas and Lockheed, were tremendously successful with the DC-2/3 and Constellation lines, respectively, and airlines all over the world have been indebted to T. W.A. for its initiatives. In peacetime, the DC-2s and 3s set the pace in airliner technology. The C-47 (military version of the DC-3) was a logistic essential to help win the War, but it would never have been developed had not Jack Frye set down the DC-1 specification in 1933. The Constellation was described by a European historian as “ America’s Secret Weapon;” and in terms of its effect on the dominance of the commercial airline skies, so it was—and again tracable to T. W.A.

Credit for inspiring the Jet Age (with the Boeing 707) must go to Pan American and its leader, Juan Trippe (the subject of the first book in this Paladwr pictorial series). But T. W.A. was not far behind, and had a large fleet of 707s, with which it was, for many years, the most popular airline on the highly competitive North Atlantic route. T. W.A.’s Boeing 747s, now retired, served so well that some of them accumulated an astonishing 100,000 hours of revenue flying service. More recently, T. W.A. has led the way by introducing the efficient ETOPS (Extended Twin-Engine Operations) practice across the Atlantic, an innovation that is now standard.

Times have changed. Intense competition in the 1970s and 1980s, brought on by airline deregulation in 1978, gave T. W.A. no credit for its pioneering that benefitted one and all. With the sale of its routes to London and other depletions, T. W.A. has had to fight for its life. In corporate strength, a proud airline, once one of the ‘Big Four,’ is but a shadow of its former self. But that is a long and distinguished shadow; and with this book, I hope that T. W.A. readers especially will take pride in their heritage, and continue to maintain that esprit de corps and the elan that has enabled them to reach the 75th anniversary of unparalleled development and achievement. Other readers, less familiar with the drama of the past, may enjoy a taste of the adventure and romance that the pioneers and leaders of Trans World Airlines have given to the airline industry, not least to their contribution to the fortunes of United States air transport, in peacetime and in war.

(Editorial note: To remind readers that the initials were always separately pronounced, the Paladwr Press house rule of full stops (periods) has been applied to the airline name: T. W.A., which is an abbreviation, not an acronym. This is to ensure that it is never pronounced ‘Twah. ’ The corporate logo omits the stops.)

Artist

Once again the Paladwr team goes into action to document the history of one of the world’s greatest airlines. I was filled with a sense of anticipation approaching excitement when Ron Davies informed me of this book, and I set out with elation to research and produce the 48 profiles of the great T. W.A. aircraft required to do justice to the cavalcade of great airliners in the airline’s history.

Artists usually derive their first inspiration from early exposure to artwork, and for me, the T. W.A. advertisements in Life magazine were among my earliest childhood memories. I would sit transfixed, staring in awe at the almost threedimensional renderings of the sleek and elegant T. W.A. Lockheed Constellations and later the first Boeing jets. They were usually depicted as flying over many of the famous romantic and faraway places that the airline served throughout the world. It was hard to believe that these realistic images were indeed paintings, as they were executed with such precision and accuracy. Even the dramatic cityscapes below were highly detailed, yet still looked correct from altitude. I also remembered seeing the artist’s name written in the background. It read “Ren Wicks.”

Years later, as a new member of the Los Angeles Society of Illustrators, I had the pleasure of meeting Ren, who was one of the founding members. He was the epitome of the classic artists who created America’s ‘Golden Age’ of commercial illustration, starting as an aviation artist for Lockheed during the Second World War. His finest work was executed while Hughes was running T. W.A. and Howard ensured that Ren was given every opportunity to attain perfection, chartering aircraft to fly him over all the cities that needed to be illustrated. He even arranged for helicopters to be assigned to Ren so that he could photograph his aerial scenes: London, Rome, Athens—all to serve as backdrops for countless images used in T. W.A.’s advertising in the 1950s and 1960s.

While in Paris on assignment in January 1998,1 learned of Ren’s passing (in his art studio—where he would have wished) at the age of 86. I was deeply honored when the Wicks family graciously allowed me to have his voluminous aviation scrap files. Upon examining the many boxfulls of photographs, blueprints, brochures, and drawings, I found much of the reference material that Ren had used for all those wonderful T. W.A. paintings that he had produced over the years. I now use this very same material as an aid to the creation of the artwork in this book, a history of the great aircraft and the people who built Trans World Airlines, and who continue the proud tradition of T. W.A. today. It has been a memorable experience, and it has also been a poignant way in which I can pay tribute with my pen and paintbrush to a fine artist whose work transcends the so-called generation gap.

(Artist’s note: in my comparison drawings (which have been a popular feature of the Paladwr pictorial books) I have, for the piston – engined aircraft, used the Constellation as the basic outline; and for the jet airliners, the Boeing 747. Otherwise, the extremes in size would be visually less relevant.)

A Delayed Beginning

The United States airline industry started to take shape only in the mid-1920s, several years after Europe, Australia, and some countries south of the Border. There had been sporadic attempts to establish individual airlines, notably by Aeroma – rine in Florida and the Great Lakes, from 1920 to 1923; but others survived for only a few months. The U. S. Post Office had pioneered a transcontinental route from New York to San Francisco. But no sustained passenger airline existed.

The Kelly Act

Then, on 2 February 1925, the Contract Air Mail Act (known as the “Kelly” Act, after its main Congressional sponsor) transferred the responsibility for carrying the air mail from the Post Office to contracted carriers. On 20 May 1926, President Coolidge signed the Air Commerce Act, which established a regulatory framework within which the airlines could operate.

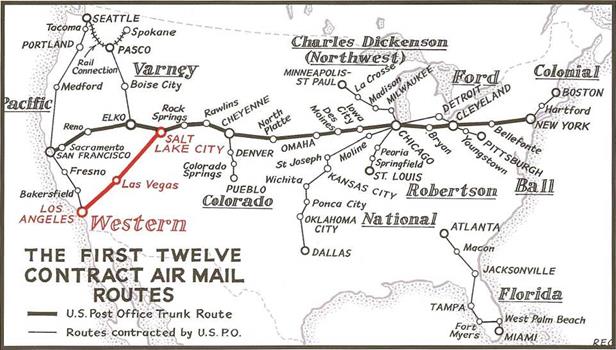

The Post Office’s Air Mail Service had grown to a stage which demanded the talents and experience of a transport organization—attributes that were considered to be outside the field of a governmental agency. The air mail routes were contracted out to private companies or to entrepreneurs who undertook to provide regular and reliable service and were paid for the service rendered. Beginning with twelve contracts let, after open bidding, in 1926, all the main cities of the United States were receiving air mail service by 1933.

T. W.A.’s Pioneering Ancestry

All the major airlines of today can trace their history back to these early beginnings. T. W.A. has a legitimate claim to be one of the true pioneers. Its ancestry began with Western Air Express (W. A.E.) which was founded on 13 July 1925, and began service on 17 April 1926. United Airlines’s ancestor, Varney Air Lines, made a flight on 6 April, but did not fly regularly until 6 June. American’s earliest ancestor, Robertson Aircraft Corporation, carried mail from 15 April, but did not at first carry passengers. Delta, too, by its acquisition of Western Air Lines in 1987, has a legitimate claim to W. A.E. ancestry.

The Innovator

Of the developments that followed the passing of the Kelly Act, T. W.A.’s were the most impressive, in that it first initiated, then sustained, and by subsequent innovations, radically directed the course of the United States airline industry during its vital formative years. And most important, these innovations proved to be of inestimable benefit to all the airlines, including T. W.A.’s competitors.

Western Enterprise

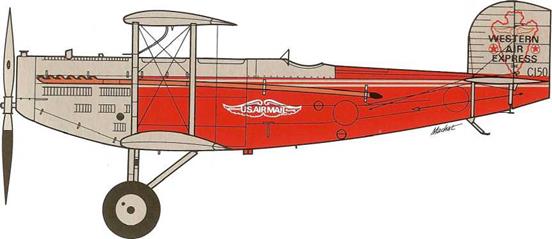

Air Mail Contract No. 4 (CAM 4) was awarded to Western Air Express (W. A.E.) of Los Angeles. Promoted by Harris ‘Pop’ Hanshue, a former racing car driver and car dealer, the airline was founded on 13 July 1925, with the backing of Harry Chandler, of the Los Angeles Times, and James A. Talbot, of Richfield Oil. With such sponsorship, it was a company of substance and enjoyed much local political and corporate influence.

W. A.E. began air mail service on 17 April 1926, from Vail Field, Los Angeles, to Salt Lake City, via Las Vegas. It connected with the established transcontinental route from San Francisco to New York, still operated by the U. S. Post Office. Hanshue aspired to winning that contract too; but lost out to Boeing Air Transport, which received the San Fran- cisco-Chicago contract in 1927.

Passengeiyservice was added on 23 May 1926. During the next seven months, 209 brave travellers paid $90 each to make the journey. They sat in an unheated and only partially protected cockpit, and were regarded as of secondary importance to the mail, which sometimes doubled as seating cushions. With no restrooms onboard, rest stops occasionally were made in the Mojave Desert. The one-way trip took 6-1/2 hours.

A total of 518 flights was scheduled for the seven months of operation in 1926, This was a remarkable record, considering that these were early stages of development of the aircraft and the standards of maintenance, not to mention the trailblazing and pathfinding talents demanded of the pilots. Bernice DeGarmo, daughter-in-law of the youngest of the pilots, neatly summed up the flying conditions: they had “no brakes, no lights, no radios.”

The Four Horsemen

In the beginning, Harris Hanshue had only four pilots to maintain that almost incredible record of regularity. Pictured on this page, they became legendary in the aviation world of California and the West at that time. The exact source of the affectionate title bestowed upon them is not recorded. One reason passed down is that it referred to the then impressive power of the Liberty engines in the Douglas mailplanes. The pilots are said to have given themselves the name, and legend has it that on occasion they backed it up by arriving for work on horseback

|

|

|

Loading the mail onto a Boeing 95 ofW. A.E. (see page 22). The pilot was Jimmy James, whose name was inscribed on his airplane.

|

|

|

Engine

|

Liberty (400 hp)

|

|

MGTOW

|

4,755 lb.

|

|

Max. Range

|

650 miles

|

|

Length

|

29 feet

|

|

Span

|

40 feet

|

|

|

The Western Fleet

The U. S. Post Office had relied upon the de Havilland DH-4B, a British light bomber design, converted to carry a load of mail; but towards the end of its operating period, the Post Office had tried other types, including the German Junkers-F 13, and it operated the Douglas mailplane. No doubt, Donald Douglas’s proximity—at Santa Monica, only just down the highway from Vail Field—had some influence on Harris Hanshue’s choice of steed for his Four Horsemen. Of the 57 Douglas Mail Planes built, W. A.E. had nine, seven of which were M-2s, and two were M-4s.

WESTERN AIR EXPRESS — THE FIRST FLEET

The Douglas M-2 Mailplane

The Douglas machine was probably the best in its day for its designated task. Its mail compartment, in front of the pilot’s cockpit, was sealed off from the engine by a fireproof wall (a practice that quickly became standard) and was lined with reinforced duralumin. The compartment was six feet long, had a capacity of 58 cubic feet, and could accommodate 1,000 lb of mail. Two removable seats could be installed for hardy passengers, or occasionally for reserve pilots.

The M-2 was developed from the M-l prototype, an action that was famously repeated by Douglas and T. W.A. eight years later. The M-2 was later improved, with the M-3, and later the M-4, with five extra feet of wingspan. Six M-2s were built, and ten M-3s. The reminder (except Western’s two) all went to the United States Post Office Department.

Preserved for Posterity

As described on page 12, one of W. A.E.’s M-4s was carefully restored and donated to Washington’s National Air and Space Museum. It was flown from Long Beach to Washington in May 1977, 46 years after it had crashed in 1930, a striking demonstration of the ruggedness and longevity of the Douglas design.

Herbert Hoover, Jr. is flanked by Jimmy James (left) and Fred Kelly (right), two of the Four Horseman. Hoover was the communications specialist for The Model Airway and Fred seems to be suggesting that a bottle opener might be useful. Herbert Hoover, Jr. is flanked by Jimmy James (left) and Fred Kelly (right), two of the Four Horseman. Hoover was the communications specialist for The Model Airway and Fred seems to be suggesting that a bottle opener might be useful.

|

Scene at Vail Field in 1926, with four Douglas M-2s and a U. S. mail truck

|

|

|

Vail Field photographed in the initial period ofW. A.E. ‘s operation, probably as it was being prepared for the opeiation.

|

|

|

|

Western Air Express established its own weather stations along the Los Angeles-San Francisco Model Airway

|

|

|

) Telephone lines (for exchange of data) > Teleprinter lines

|

|

|

|

WESTERN’S FOKKER F-14s (Single Engined)

|

|

|

MSN

|

Regn.

|

Delivery

Date

|

Fleet No.

|

Remarks

|

|

1404

|

NC129M

|

Sep 29

|

400

|

1

|

|

1408

|

NC327N

|

|

|

|

|

1409

|

NC328N

|

Nov 29

|

401

|

> To T. W.A.

|

|

1411

|

NC331N

|

Feb 30

|

402

|

J

|

|

|

12 seats *110 mph

|

Engines

|

Pratt & Whitney

|

|

Wasp (420 hp) x 3

|

|

MGT0W

|

12,500 lb.

|

|

Max. Range

|

300 miles

|

|

Length

|

50 feet

|

|

Span

|

79 feet

|

The Fokker F-10

This was one of the Fokker transport airplanes that were built only in the United States. They can be distinguished from Dutch-built Fokkers in that arabic, not roman, numerals were used for the type designations. Other U. S. Fokker types were the Universal and Super Universal (page 18), the F-32 (page 21) and the F-14 (page 22).

Chosen Instrument

Western spent its entire $ 180,000 from the Guggenheim Fund to purchase three Fokker F-10 tri-motors. The Fokker had three Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines; it could maintain altitude with only one, and could climb to 7,000 feet with two. The F-10 had wheel brakes, a lavatory, a lighted instrument panel, and “full cabin-length windows” that could be opened in flight to let in the fresh air. Fokker built 65 of these early ‘airliners’ of which 58 were F-lOAs. Until the highly publicized T. A.T. disaster of March 1931—the notorious Knute Rockne crash—the Fokker was considered to be as good as the Ford Tri-Motor. Western spent its entire $ 180,000 from the Guggenheim Fund to purchase three Fokker F-10 tri-motors. The Fokker had three Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines; it could maintain altitude with only one, and could climb to 7,000 feet with two. The F-10 had wheel brakes, a lavatory, a lighted instrument panel, and “full cabin-length windows” that could be opened in flight to let in the fresh air. Fokker built 65 of these early ‘airliners’ of which 58 were F-lOAs. Until the highly publicized T. A.T. disaster of March 1931—the notorious Knute Rockne crash—the Fokker was considered to be as good as the Ford Tri-Motor.

|

View of the Fokker F-10, showing the characteristic thick-chonl Fokker wooden wing.

|

|

|

AIRCRAFT ON THE ROUTE TO AVALON

|

|

|

MSN

|

Regn.

|

Remarks

|

|

Curtiss HS-2L

A-1373

A-1981

111

|

NC652

NC2420

NC5419

|

I Operated by Pacific wfu Jul 29 l Marine, 1922-28 wfu May 29 J Fleet Numbers 225-227

|

|

Loening C-2H

220

230

|

NC9773

NC135H

|

1 Ordered by Pacific Marine, delivered to W. A.E., Mar/Jun 29; і Fleet Numbers 301-302; sold May 31

|

|

Sikorsky S-3J

14-5

|

A

NC8031

|

Flying Fish, Fleet Number 300; delivered to W. A.E., Oct 28; written off, Avalon, 5 Jun 29

|

|

Boeing 204

1076

|

NC874E

|

Delivered May 1929, Fleet Number 228; sold to Gorst Air Tpt., 7 Jen 31

|

|

|

|

|

|

Airofher Passenger Airline

While Western Air Express had introduced passenger service along the California corridor, another enterprising company was doing the same (also without a mail contract) in the south. The Aero Corporation of California, an aircraft dealership and flying school, had formed a subsidiary, Standard Airlines, on 3 February 1926, incorporating it (as a Nevada Corporation) on 1 May 1928.

Creature Comforts

The Fokker Universals and a F-VIIa which at first comprised Standard’s fleet were adequate to fly from Los Angeles to Tucson; but the journey was quite long when service started on 28 November 1927. Recognizing a need, it provided onboard “comfort facilities limited to men.’’ But a brief stop was made for women at Desert Center, where “a solitary filling station boasted two crude outhouses.”

Transcontinental Ambitions

Standard’s officers included Lieut. Jack Frye, president; Paul Richter, Jr., treasurer; and Walter Hamilton, 2nd vice-president. As early as 4 February 1929, Frye announced the inauguration of “America’s First Transcontinental Air-Rail Travel Route.” This claim was made by extending its route beyond Tucson to El Paso, where it connected with the Texas and Pacific Railroad. The claim became more legitimate, albeit still stretching the definition a little, when the coast-to-coast linkage was completed on 4 August of that year by an alliance with Southwest Air Fast Express and the New York Central Railroad.

STANDARD AIR LINES

Purchased by Western Air Express, 1 May 1930

Los Angeles. —*3^ p El Paso

Service opened Phoenix

28 Nov. 1927 Tucson’ __

Douglas

Harris Hanshue expanded Western Air Express’s network considerably during 1929 and 1930, as shown in the map on page 20. The purchase of Standard Air Lines consolidated W. A.E. ’a grip on the airways west of the Rockies, but the T. A.T. merger reduced Hanshue’s influence and he sold this southern transcontinental link to American Airways in October 1930, to complete the latter’s coast-to-coast link-up.

| |