. Fokker F-32

|

Engines |

Pratt & Whitney |

Range |

400 miles |

|

Hornet В (575 hp) x 4 |

Length |

70 feet |

|

|

MGTOW |

24,250 lb. |

Span |

99 feet |

![]()

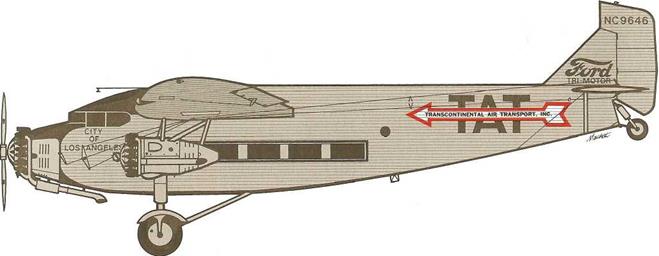

A Giant Before its Time

The Fokker F-32 was the largest aircraft to enter airline service—briefly—until the introduction of the Douglas DC-3 in 1936. It had four engines, mounted in tandem, suspended from the typical Fokker thick-aerofoil wooden wing. Western introduced it on 17 April 1930, and it provided hitherto unprecedented service between Alhambra and Oakland. It had four plush compartments, with well-upholstered reclining seats. There were call-buttons for a steward—a Western innovation—lavatories, folding tables, galleys, and reading lights.

Hour of Glory

There were some technical features of note. The instrument panels were better than those in any previous aircraft. The fuel tanks were kept well away from the passengers, in the wings, which was another innovation. Each engine had its own fire-extinguishing system; but unfortunately this had to be used too often. Western operated two aircraft for several months in the summer of 1930. But after the much-publicized Fokker F-10 crash in March 1931, its wooden construction came into disrepute, and the type was grounded. Nevertheless, Western Air Express had had the honor of operating their first four-engined transport airplane in the United States; and although Universal Air Line System ordered the F-32, Western was the only one to operate it.

WESTERN’S FOKKER F-32 (Model 12) FLEET

|

![]()

The Master Plan

President Hoover’s Postmaster-General, Walter Folger Brown, was the architect of the system of air transport routes that became the foundation of the United States airline industry as we know it today. Having studied the multiplicity of railroads, numbering close to 300, none of which spanned the continent, he devised a plan that was based on three or four coast-to-coast trunk routes, connected by several north-south routes to form a consolidated grid pattern. This required the amalgamation of some of the initial contracts granted from 1926 to 1929. and most of the airlines, realizing the potential, complied with Brown’s wishes. One outcome was the emergence of transcontinental giants such as United Air Lines and American Airlines.

Conflicting Claims

Brown did not approve of the idea of two operators on the same route, both claiming air mail payments. The United, American, and Northwest transcontinental routes emerged without much trouble; but for the south central route, serving many important cities, Western Air Express and the newly – formed Transcontinental Air Transport (T. A.T.) both wanted the coveted CAM 34 contract.

Both had good claims. Western was operating from California to several mid-western cities (see page 20). T. A.T. spanned the continent with a well-promoted air-rail service. But Brown was not going to break his own rales, and open the floodgates for other disputes and claimants. What became known as the Shotgun Marriage was solemnized by Brown on 16 July 1930. The two names were merged on 24 July 1930, to become Transcontinental & Western Air (T. W.A.), with Han – shue as its first president.

Curious Precedent

As it enters the 21st century, air transport throughout the world is improving inter-modal connections between airline service and high-speed rail. Methods of passenger transfer today could learn lessons from the amenities offered by T. A.T. in 1930. Cooperation, rather than competition between the different modes, could have advantages today—as it did then.

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

![]()