Performance Goals

When the United States entered the Second World War in December 1941, the venerable twin-engined Douglas DC-3 was standard equipment. On the domestic front, only T. W.A. had a better airliner, the four-engined Boeing 307. It was faster than the DC-3 (220 v. 160 mph) and far more comfortable, flying as it did ‘above the weather’ (20,000 v. 8,000 feet). But its range was not outstanding.

Dramatic Debut

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh’s solo trans-Atlantic flight changed the air-mindedness of an entire nation: the press, the public, the politicians, and the industrialists. In 1944, the airline world was unexpectedly confronted with another record flight, with almost comparable consequences. With one dramatic gesture, Howard Hughes electrified the political scene in Washington, and changed the course of progress in commercial aviation technology.

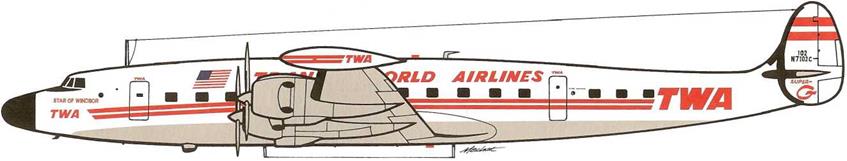

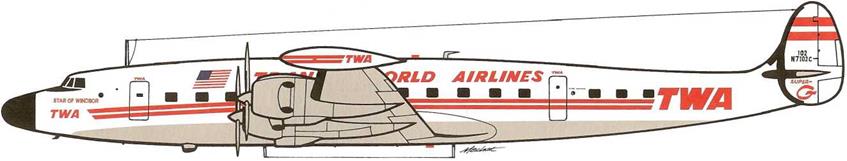

The Lockheed Constellation had been built at Burbank under the direction of designer Hal Hibbard to the precise specifications of Hughes, whose experience as an aviator and industrialist, with instinctive intuition, combined with his extensive financial resources, were injected into the design and construction of an historic prototype.

Moment of Triumph

On 17 April 1944, Howard Hughes and Jack Frye flew the prototype Model 49, soon to be called the Constellation, from Burbank to Washington’s National Airport in the transcontinental record time of 6 hours, 57 minutes. The effect on a skeptical administration and military hierarchy was startling. After flying some congressmen and top military brass on sightseeing flights, Hughes turned the new airplane over to Air Transport Command. T. W.A.’s owner and Lockheed’s design team had ushered in a new era in air transport.

America’s Secret Weapon

The Constellation reinforced the supremacy of United States aeronautics. Peter W. Brooks, distinguished British airline historian, described the aircraft as “the secret weapon of American air transport.” He pointed out that in 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War, the British aircraft industry, whose technical talent was possibly on a par with the American, in quality if not in quantity of production, had regarded the DC-4 as the competitive standard. But when the War was over, the Constellation swept all before it.

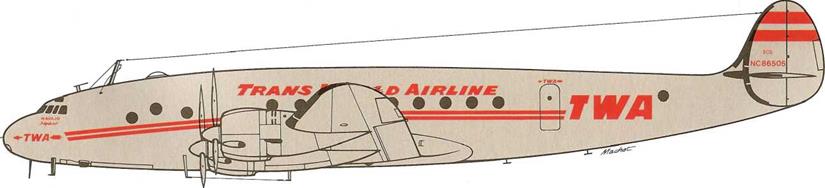

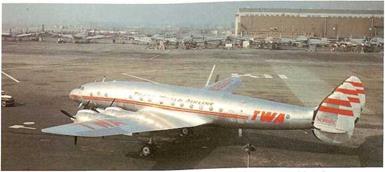

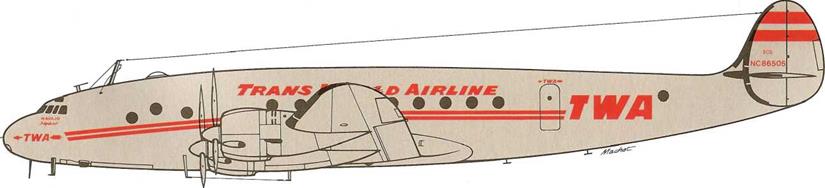

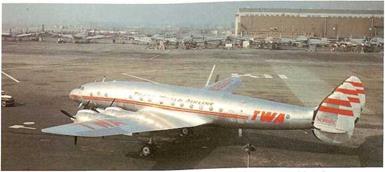

The 049 Constellation was similar in appearance to the later 749 model, differing only in window configuration and engine cowling detail.

Initial Snags

T. W.A. acquired 88 of the standard Constellations. Six were ex-military C-69s; 41 were Model 49s (later amended to 049s); and the remaining 41, with more powerful engines, Model 749s. The inauguration of Atlantic services, on 5 February 1946, is described on page 50. Domestic services with the Connie began ten days later, and after preliminary trial services on shorter routes, coast-to-coast service from New York to Los Angeles began on 1 March. But the satisfaction was short-lived. During the early life of the airplane, several problems had had to be overcome. The substantially increased performance carried with it increased complexity, and the Constellation was not immune from the technical ‘teething troubles.’ Then, from 12 July to 20 September 1946, the fleet was grounded because of a leaking fuel system. No sooner was this fixed when the pilots went on strike, from 21 October to 15 November.

Ambition Fulfilled

By this time, however, T. W.A. was staking its claim to be a fully-fledged international airline. The European routes were extended to Cairo on 1 April 1946, to Lisbon and Madrid on 1 May, and to Bombay on 5 January 1947. All these were inaugurated with the Constellations. This fine airliner, in spite of an initial reputation of unreliability, soon got into its stride. It was 70 mph faster than the DC-4, had 60 seats against 44 at the same seat pitch, and could fly across the Atlantic with only one stop instead of two. It sent the Douglas designers and engineers back to their drawing boards in a hurry, to produce pressurized variants of the old Skymaster.

Many airlines purchased the Constellation, and although the DC-4 filled the bill for a postwar year or two, most of the trans-Atlantic airlines had the Lockheed airliner in service by the late 1940s. The British airline, B. O.A. C., had to have them too, as the home industry’s commercial airliner projects had been cancelled at the outbreak of the War in 1939.

But until the advent of the Jet Age in 1958, the world of airlines watched T. W.A. as it successively introduced newer and faster versions of the classic Constellation series.

Engines Wright R-3350 (2,200 hp) x 4 Length

MGT0W 86,250 lb. Span

Max. Range 3,000 miles Height

‘This aircraft made T. WA.’s inaugural trans-Atlantic flight, New York-Gander-Shannon-Paris (Le Bourget) on 5 Feb 46, in a block-to-block time of 19 hr 46m. NA: Sold to Nevada Airmotive, 31 March 1962

*This aircraft made TWA’s last scheduled commercial Constellation flight, Flight 249, on 6 April 1967. AT: These aircraft sold to Aero-Tech Inc. in May, June, and August 1968.

This is a listing of all the 87 Constellations in T. W.A.’s fleet. From the first famous delivery flight to Washington on 17 April 1944 to the last one by T. W.A. on 6 April 1967, 23 years had elapsed. This was, in the period of the piston- engined airliners, an impressive record. The list does not include the Super Constellations and Starliners, reviewed in the following pages.

|

|

|

Although the 600-gallon tip tanks gave the ‘Super G’a distinctive appearance, not all ofTWA’s 1049Gs were so equipped. Tip tanks were used primarily for international routes.

|

|

|

Fleet

No.

|

Regn.

|

MSN

|

Date into Service

|

Name

|

Disposal and Remarks

|

|

Series 1

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

|

049 (Mode

N6901C N6902C N6903C N6904C N6905C N6906C N6907C N6908C N6909C N6910C

|

1049-54-£

4015

4016

4017

4018

4019

4020

4021

4022

4023

4024

|

0)

9 Oct. 52 16 Aug. 52 16 Aug. 52 27 Aug. 52

2 Oct. 52 27 Sep. 52 18 Oct. 52 27 Sep. 52 26 Oct. 52

3 Nov. 52

|

Star of the Thames Star of the Seine Star of the Tiber Star of the Ganges Star of the Rhone Star of the Rhine Star of Sicily Star of Britain Star of Tipperary Star of Frankfurt

|

Sold to California Hawaiian, 28 Oct. 60 Crashed in the Grand Canyon, 30 Jun. 56 Sold to South Pacific Airlines, 1 Jun. 62

| Sold to Florida State Tours, 7 Aug. 64

Sold to California Airmotive, 15 Feb. 60 Crashed, New York City, 16 Dec. 60

| Sold to Florida State Tours, 7 Aug. 64

|

|

Series 1

|

049G (Mot

|

el 1049G-82-110)

|

|

|

|

101

|

N7101C

|

4582

|

21 Sep. 55

|

Star of Balmoral

|

Crashed at Chicago (Midway), 29 Feb. 60

|

|

102

|

N7102C

|

4583

|

17 Mar. 55

|

Star of Windsor

|

Temporarily named The United States. Flew inaugural Super

|

|

|

|

|

|

G service, 30 March 1955. Scrapped, 4 Feb. 64

|

|

103

|

N7103C

|

4584

|

14 Mar. 55

|

Star of Buckingham

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 3 May 65

|

|

104

|

N7104C

|

4585

|

17 Mar. 55

|

Star of Blarney Castle

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 1 Sep. 65

|

|

105

|

N7105C

|

4586

|

14 Mar. 55

|

Star of Chambord

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 12 Dec. 66

|

|

106

|

N7106C

|

4587

|

23 Apr. 55

|

Star of Ceylon

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 4 Jan. 67

|

|

107

|

N7107C

|

4588

|

1 Apr. 55

|

Star of Carcassome

|

Scrapped 7 Nov. 63

|

|

108

|

N7108C

|

4589

|

31 Mar. 55

|

Star of Segovia

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 25 Jun. 65

|

|

109

|

N7109C

|

4590

|

21 Apr. 55

|

Star of Granada

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 10 Nov. 61

|

|

110

|

N7110C

|

4591

|

8 May 55

|

Star of Escorial

|

Scrapped 14 Apr. 64

|

|

ж

|

N7111C

|

4592

|

10 May 55

|

Star of Toledo

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 4 Jan. 67

|

|

112

|

N7112C

|

4593

|

11 May 55

|

Star of Versailles

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 5 Dec. 66

|

|

113

|

N7113C

|

4594

|

11 May 55

|

Star of Fontainebleau

|

Sold to California Airmotive, 15 Feb. 67

|

|

114

|

N7114C

|

4595

|

2 Jun. 55

|

Star of Mont St. Michael

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 13 Jul. 65

|

|

115

|

N7115C

|

4596

|

29 May 55

|

Star of Chilton

|

Crashed at New York (JFK) 26 Jan. 66

|

|

116

|

N7116C

|

4597

|

4 Jun; 55

|

Star of Heidelberg

|

Scrapped 8 Apr. 64

|

|

117

|

N7117C

|

4598

|

5 Jun. 55

|

Star of Kenilworth

|

Sold to Aaron Ferer & Sons, 1 Oct. 65

|

|

118

|

N7118C

|

4599

|

9 Jun. 55

|

Star of Capri

|

Scrapped, 11 Jan. 64

|

|

119

|

N7119C

|

4600

|

1 Jul 55

|

Star of Rialto

|

Scrapped 10 Jun. 64

|

The aircraft said to Aaron Ferer & Sons were resold and scrapped at Tucson. The aircraft sold ta California Airmotive were scrapped at Fox Field, Lancaster.

|

|

|

Engines Wright 972TC Turbo-compounds (3,250 hp) x 4 Length 114 feet MGTOW 137,5001b. Span 123 feet

Max. Range 3,500 miles Height 25 feet

|

|

|

Engine Problems

Elegant though the Constellation was, and impressive though its performance, this fine airliner did have its problems, not least because its designers were always trying to advance the levels of technology. One of the main problems was the Wright R-3350 turbo-compound engines, which consistently gave trouble, to the extent that Claude Girard, the senior pilot of the relief truck, described on this page, claimed that the crews “logged more flying time on three engines than four.” At first, a C-47 was based in Paris to ship the piston engines to distant points, as T. W.A. had spread its wings to the far comers of Europe and southern Asia. But with the Jet Age approaching, with much larger engines, the decision was made to base a specialized engine-carrier in Paris.

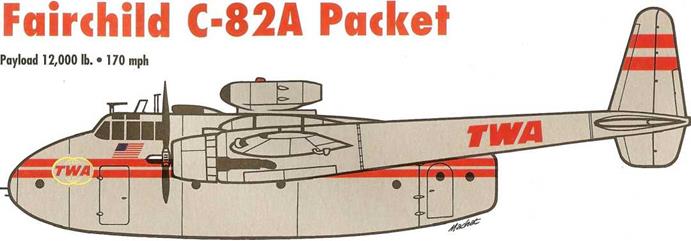

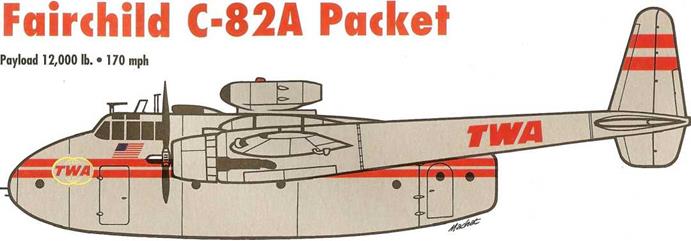

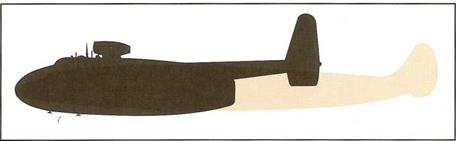

The C-82

Larry Trimble, T. W.A.’s operational chief in Paris, found the answer in a twin-boomed Fairchild C-82 Packet which he discovered in Tel Aviv in 1956. It took eight months of work, with much overtime, totalling 10,000 man-hours, to ‘civilianize’ the C-82. To increase the loadcarrying capability and airfield performance, a Westinghouse 3,250-lb- thrust J-34 jet engine was installed on top of the fuselage for auxiliary power, and to raise the take-off weight to 54,000 lb. A Volkswagen engine APU (auxiliary power unit) was also installed to power an electric windlass to haul aboard the disabled engines.

The Thing

The C-82’s performance was sluggish and the airplane was not easy to handle. Compared to the elegant Constellations, it was distinctly unhandsome. The crews named it Ontos, which is the Greek word for “Thing.” Ugly duckling it may have been; but it did its job well, entering service with T. W.A. In 1957, it was registered, as a matter of local convenience, ET-T-12, which had been the Ethiopian number for the displaced C-47. Ethiopian was one of the airlines that T. W.A. was closely associated with, either as part-owner or as technical and operational adviser. Eventually, Ontos was certificated by the F. A.A. on 1 March 1960, and registered as N9701F. It carried engines everywhere throughout the eastern hemisphere, flying regularly to Manila, Bombay, and Nairobi, with Constellation replacement engines. In 1968 alone, now hauling Boeing 707 engines too, there were 68 unscheduled overseas engine replacements

Artist’s Note

T. W.A. ’s C-82 was substantially modified fi-om its original post-World War Two configuration. Note the modern avionics antennae and J-34 jet engine pod mounted above the fiiselage.

|

Engines

|

Pratt & Whitney R2-800-85 (2,100 hp) x 2

|

Length

|

77 feet

|

|

NIGTOW

|

54,000 lb.

|

Span

|

107 feet

|

|

Range

|

500 miles

|

Height

|

26 feet

|

After twelve years of faithful service, un-noticed by the media as the Jet Age was augmented by the 747s and other more publicity-worthy wide-bodied giants, the “Thing” was retired on 13 January 1972, and sold the following year to an American airborne delivery firm, Briles Rotor & Wings.

|

I Photo courtesy Roger Bentley collection)

|

|

(picture courtesy Richard and Bernice DeGarmo, Al’s son, and daughter-in-law)

|

Air Mail Special

One of the more unusual of T. W.A.’s “firsts”is that, of all the airlines established in 1925 as the result of the Kelly Air Mail Act, it carried the first passenger. He was not even the official recipient of Western Air Express’s ticket No. 1 (see page 6) but he did precede Mr. Ben Redman, who had that privilege. Not only was Will Rogers the first passenger in T. W.A.’s 75-year history, he was the first famous personality of the dozens of celebrities who were later to make Howard Hughes’s company the Airline of the Stars.

The civil air mail regulations required that, before an airline could carry passengers, it had to carry the mail for 90 days, or at least for a trial period (see page 9). A1 DeGarmo, one of the Western’s legendary Four Horsemen (see page 10), was a friend of Will Rogers, then a vaudeville entertainer, noted for his prowess with rope tricks, later to become famous for his droll commentaries on the human condition. In a conspiracy that evaded the law — the lawyers would have had a lovely time in the courts — Will stuck a quantity of stamps on the back of his jacket and mailed himself to Salt Lake City and back.

In 1926, the pilots were not noted for their sartorial elegance, as they are today. But their attire was practical, and included a side-arm. This was to guard the mail, and in this case, presumably, to guard Will Rogers as well.

Los Conquistadores del Cielo

Another of T. W.A.’s lesser-known “firsts’ is that it inspired the foundation of that exclusive aviation club. The idea originated when in 1937 the airline obtained widespread support among political and business circles for its cut-off route to San Francisco, branching off northwestwards from Winslow, thus avoiding the circuitous route via Los Angeles and a connection on to Western Air Lines, via Las Vegas (see page 38).

President Jack Frye wanted to make a token reward to all the influential supporters who had enabled him to win approval for this important access to San Francisco. John Walker, Frye’s vice-president, suggested a weekend celebration in September 1937 for 60 guests at the Forked Lightning Ranch in Albuquerque. A great time was had by all, including horseback riding, fishing, and a dude rodeo — at which Jack Frye showed that he was no mean hand at roping steers, at least small steers.

The general consensus was “let’s do it again.” and John Walker once again came up with the idea of linking an annual event with the Spanish tradition of the south-western states, the locale of the cut-off route. And so was bom Los Conquistadores del Cielo, named after Francisco de Coronado, the Spanish conquistador who had annexed the whole area for Spain.

Jack Frye was elected president and 91 senior aviation aficionados were inducted on 16-18 September 1938 in a colorful initiation ceremony. This has been enhanced by a dress code, introduced by Walker in 1951: replicas of the raiment worn by Hernan Cortes and the original conquistadores. The Conquerors of the Skies meet every year, at different venues, in an elite association that owes its origins to a T. W.A. route extension.

|

(courtesy: Constance Walker)

|

|

(courtesy: Ona Gieschen)

|

Flooded Out

In July 1951, there was a great flood in the Missouri River valley, covering an extensive area of low-lying land around Kansas City, where the confluence with the Kansas River exacerbated the disaster. T. W.A.’s engineering base was then at the Fairfax airport (see page 107) which was vulnerable to flooding. In this picture a lone DC-3 can be seen stranded in the waters, but T. W.A. flew the other resident aircraft to higher ground.

|

(courtesy: Ona Gieschen)

|

Historic Greeting

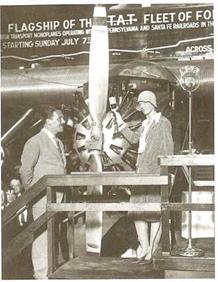

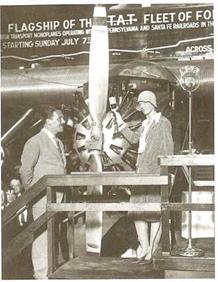

As narrated on page 52, one of the pivotal events in air transport history was the dramatic flight in 1944 of the first Lockheed Constellation, when Howard Hughes and Jack Frye delivered the prototype from Burbank to Washington in a transcontinental record time, (see page 52) They are pictured here on arrival at Washington’s National Airport with (left) William A. M.Burden, Assistant Secretary of Commerce; and Jesse Jones, Secretary of Commerce.

Jack Maddux

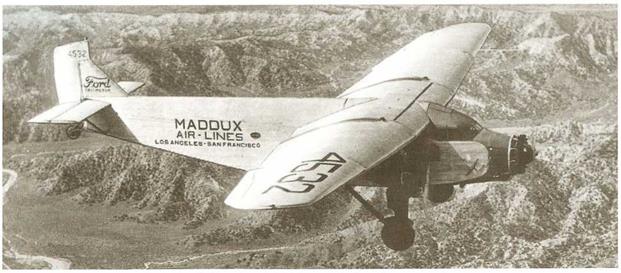

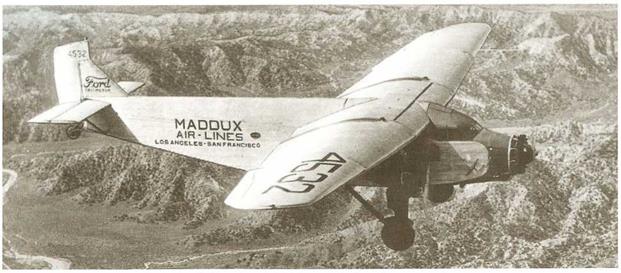

Harris Hanshue’s Western Air Express and Jack Frye’s Standard Airlines were not the only airlines of substance among the many which recognized the possible potential for airline operations in the booming California of the late 1920s. Jack L. Maddux, a Los Angeles Lincoln car dealer, took delivery of a Ford 4-AT Tri-Motor and incorporated Maddux Air Lines on 9 September 1927. His activities were overshadowed by other events, not least by Charles Lindbergh’s historic trans-Atlantic flight in May of that year and the Goodwill Tour of the 48 States that followed. Maddux’s contribution to the development of the airline business in the West has long been under-recognized, except by historians such as Ed Betts and Bill Larkins, whose research has preserved the memory of the Maddux operation.

Service Begins

Maddux began airline service on 1 November 1929 from Rogers Field, Los Angeles, to San Diego. He did it in style. For the occasion, Lindbergh was the honorary chief pilot. But like most of the aspirant airlines in California, he had no mail contract to supplement the passenger revenues. Nevertheless, he was very successful and popular. On 15 November, he added service to Agua Caliente, just across the Mexican

MADDUX AIR ONES FORD TRI-MOTORS

|

One of Maddux Air-Line’s Ford 4-ATs flying near the Tejon Pass, north of Los Angeles.

|

|

|

Maddux was one of the earliest airlines to cooperate with United Parcel Sendee (UPS) in carrying goods by air.

|

|

|

|

Artwork size does not allow accurate scale representation of the Tri-Motor’s corrugated aluminum skin.

|

|

|

Jack Maddux is seen here with Charles Lindbergh, who flew the inaugural flight, (photo courtesy Bill Larkins)

|

|

|

Engines

|

Wright R-975 Whirlwind (220 hp) x 3

|

Length

|

50 feet

|

|

MGT0W

|

10,130 lb

|

Span

|

74 feet

|

|

Range

|

500 miles

|

Height

|

12 feet

|

|

|

border, for thirsty Prohibition sufferers and for clients of the race-track and casinos there. On 14 April 1928, he started a twice-daily service from Los Angeles to San Francisco (Oakland), with optional stops at Bakersfield, Visalia, and Fresno. By the end of the year, his fleet comprised eight Fords, two Lockheed Vegas, and two Travel Airs.

Ford Promotion

Maddux began 1929 in style, adding a daily service to Phoenix (paralleling Standard), together with some local routes in California. Early in the year, the San Francisco terminus was transferred to Alameda, and the Los Angeles terminus to Glendale. Jack Maddux had assembled the largest fleet of Ford Tri-Motors, eight 4-ATs and eight 5-ATs plus two Lockheed Vegas. The only loss was when an Army pilot, doing some stunt flying, hit a 5-AT in mid-air. Maddux had not apparently sought an air mail contract, but his 16 pilots carried 40,000 passengers in 1929.

Historic Merger

In the summer, he started to negotiate with the new well-capitalized T. A.T., which began its highly-publicized coast-to-coast air-rail service on 7 July. Charles Lindbergh flew the inaugural flights for both airlines. Another important Maddux employee was Vice-president of Operations Lt. D. W. ‘Tommy’ Tomlinson, an ex-Navy pilot, and who was to play a key role in subsequent developments, when on 16 November 1929, Jack Maddux merged with T. A.T. and became president of the combined airline. T. A.T.-Maddux. Through this merger, T. A.T. was able to serve the two big Californian cities. Los Angeles and San Francisco, both growing quickly in population, wealth, and consequent travel potential.

The Ford Tri-Motors Compared

Consolidation of a Great Airline

Postmaster General Brown’s analytical planning had produced a fine transcontinental route. The Maddux merger had given T. A.T. direct service to all three of the large urban concentrations in California. But the formation of T. W.A. had been a complicated affair, because Pittsburgh Aviation Industries Corporation (P. A.I. C.) had started service from Pittsburgh to New York, via Philadelphia, with two Travel Airs, in December 1929, and had staked its claim. The threat to Brown’s master plan was neatly solved by dividing the stock of the merged company in the ratio 47.5% T. A.T., 47.5% W. A.E., and 5% P. A.I. C. After a legal delicacy, with the formation of the Eton Corporation on 19 July 1930, Transcontinental & Western Air (T. W.A.) was formed five days later. The coveted mail contract was awarded on 25 August. Although Harris Hanshue was made president of the new company, he quickly became disillusioned. R. W. Robbins, of P. A.I. C., took over the presidency in September 1931. Another contender, a group called United Avigation, was disposed of by the offer of a lucrative mail contract on a route sub-leased from American Airways.

End of the Air-Rail

With the completion of the Lighted Airway, and the improvement of aircraft reliability, the pioneering air-rail service came to an end. On 25 October 1930, the train connections were dropped and the Fords flew the whole route, coast-to-coast, in 36 hours, with an overnight stop at Kansas City. On 5 November 1932, even the overnight stop was dropped and the Fords flew by day and by night. Nevertheless the journey must have been arduous. The Ford’s engines were noisy, and passengers were issued ear plugs and chewing gum. Another development had been the shipment of livestock on 6 August 1931, one of the first examples of air freighting in the United States.

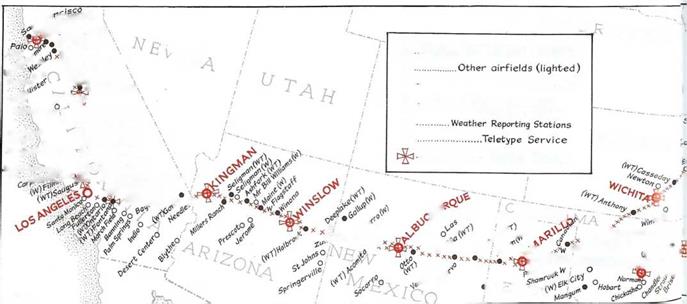

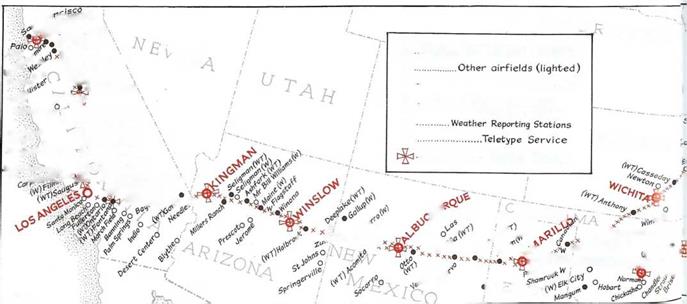

Superb Planning

All this was achieved only by some masterly planning. This is well illustrated by the map on this double-page spread, based on an original blueprint, signed by Jack Frye, but undoubtedly the work of T. W.A.’s technical consultant, Charles Lindbergh, who carried out the detailed surveys. He had a personal aircraft for the arduous travelling involved, and was paid $10,000 per year (a tidy sum in those days) plus 25,000 shares of T. W.A. stock, sold at well below market value.

|

Transcontinental

&

Western Air, inc.

America’s First 36-Hour

Transcontinental Passenger Service

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

jf^ ,v0 x x wWoynoka (WT)

* * Fargo (WT) x* .

uA „ьТ Gia*ier(wT) J? ,*r,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The final development of the famous Constellation series of airliners was the Model 1649A, introduced by T. W.A. on 1 OJune 1952. At first it was called the Super Star Constellation (by Lockheed). T. W.A. called it the “Jetstream Starliner”, possibly to try to persuade passengers that this aircraft was as good as any of the jets that were about to enter service in 1958, or the long-range turboprop Bristol Britannia that was outpacing the piston-engined airliners in speed, comfort, and low noise level. But this name gave way to the Starliner, which fitted neatly with the names of the individual aircraft in T. W.A.’s fleet. It was a fine performer, able to cross the Atlantic from New York to Paris or London nonstop in both directions. It was the

Lockheed 1649Д Starliner (Model 1649A-98-20 except as noted)_____________________

|

|

|

Engines Wright 998TC (3,400 hp) x 4 Length 116 feet

MGTOW 156,000-160,000 lb. Span 150 feet

Range 4,000 miles Height 25 feet

ultimate piston-engined airline flagship, and, as shown in the following pages, was roomy enough to offer several classes of service, and able to compete with Pan American’s first-class – only Stratocruisers.

|

|

|

Fleet

No.

|

Regn.

|

MSN

|

Date into Service

|

Name

|

Disposal and Remarsk

|

|

316

|

N7316C

|

1018

|

28 Jun 58

|

Star of the Tigris

|

Converted to freighter, Nov. 60. Sold to Alaska Airlines, 31 Dec 62

|

|

317

|

N7317C

|

1019

|

1 Jul 57

|

Star of the Clyde

|

Converted to freighter, Oct 60. Sold to California Airmotive, 11 Aug 67

|

|

318

|

N7318C

|

1021

|

30Jul57

|

Star of the Arno

|

Sold to Bush Aviation, 27 Dec 65

|

|

319

|

N7319C

|

1022

|

26 Jul57

|

Star of the Loire

|

Converted to freighter, Nov 60. Sold to Bush Aviation, 10 May 66.

|

|

320

|

N7320C

|

1023

|

27 Jul 57

|

Star of the Avon

|

Sold to Transatlantica (Argentina), 11 Aug 61. Reclaimed and sold to Bush Aviation, 15 Dec 65

|

|

321

|

N7321C

|

1024

|

2 Aug 57

|

Star of the Euphrates

|

Sold to Bush Aviation, 8 Oct 65

|

|

322

|

N7322C

|

1025

|

30 Jul 57

|

Star of the Po

|

Converted to freighter, Dec 60. Sold to California Airmotive, 29 Aug 67

|

|

323

|

N7323C

|

1029

|

16 Aug 57

|

Star of the Aegean

|

Converted to freighter, Apr 61. Sold to Bush Aviation, 9 Dec 65

|

|

324

|

N7324C

|

1030

|

24 Aug 57

|

Star of the Danube

|

Converted to freighter, Apr 61. Sold to Aero-Tech, 24 May 68

|

|

325

|

N7325C

|

1035

|

17 Sep 57

|

Star of the Meuse

|

Sold to Arizona Aircraft & Parts, 30 Sep 66

|

|

326

|

N8083H

|

1038

|

18 May 58

|

Model-98-16. Built for

|

, Sold to Alaska Airlines, 31 Dec 62

|

|

327

|

N8082H

|

1037

|

1 May 58

|

Linee Aeree Italiane

|

1 Sold to Bush Aviation, 26 Oct 65

|

|

328

|

N8084H

|

1039

|

4 May 58

|

(L. AI.) but not deliv-

|

| Sold to Aero-Tech, 13 Jun 68

|

|

329

|

N8081H

|

1026

|

30Jun 58

|

ered. Converted to freighters, Mar 61.

|

1 Used as engine carrier Jun 62-Dec 66. Sold to California Airmotive, 6 Sep 67

|

The names allocated to Fleet Nos. 310 onwards were not displayed on the aircraft.

|

|

|

Fleet

No.

|

Regn.

|

MSN

|

Date into Service

|

Name

|

Disposal and Remarks

|

|

301

|

N7301C

|

1002

|

8 Sep 57

|

Star of Wyoming

|

Model-98-11. Sold to Bush Aviation, 14 Oct 63

|

|

302

|

N7302C

|

1003

|

2 Jun 57

|

Star of Utah

|

Model-98-09. Sold to Bush Aviation, 21 Oct 65

|

|

303

|

N7303C

|

1004

|

1 Jun 57

|

Star of Vermont

|

Model-98-23. Scrapped 24 Sep 62

|

|

304

|

N7304C

|

1005

|

14Jun 57

|

Star of Rhode Island

|

Model-98-03. Sold to Bush Aviation, 28 Oct 65

|

|

305

|

N7305C

|

1006

|

1 Jun 57

|

Star of Idaho

|

Model-98-09. Sold to Transatlantica (Argentina) 12 Sep 60

|

|

306

|

N7306C

|

1007

|

1 Jun 57

|

Star of Maryland

|

Model-98-09. Temporarily named Spirit of St. Louis. Scrapped 26 Ap. 62

|

|

307

|

N7307C

|

1008

|

3 Jun 57

|

Star of Montana

|

Model-98-09. Sold to Transatlantica (Argentina) 3 Oct 60. Reclaimed by T. W.A. Nov 61. Sold to F. A.A.12 Feb 64

|

|

308

|

N7308C

|

1009

|

2 Jun 57

|

Star of Oklahoma

|

Model-98-22. Sold to Transatlantica. 30 Aug 61. Reclaimed Nov 61. Sold for scrap to Arizona Parts & Spares 30 Sep 66

|

|

309

|

N7309C

|

1010

|

3 Jun 57

|

Star of Maine

|

Model-98-22. Sold to Arizona Parts & Spars, 30 Sep 66

|

|

310

|

N7310C

|

1012

|

21 Dec 57

|

Star of Kansas

|

Model-98-22. Sold to Delta Aircraft & Equipment 29 Apr 64

|

|

311

|

N7311C

|

1013

|

4 Jun 57

|

Star of the Ebro

|

Converted to freighter, Oct 60. Sold to California Airmotive, 20 Sep 67

|

|

312

|

N7312C

|

1014

|

17 Jun 57

|

Star of the Elbe

|

Sold to Arizona Aircraft 8, Parts, 30 Sep 66

|

|

313

|

N7313C

|

1015

|

1 Jun 57

|

Star of the Severn

|

Crashed at Milan, Italy, 26 Jun 59

|

|

314

|

N7314C

|

1016

|

1 Jul 57

|

Star of the Shannon

|

Sold to Moral Rearmament Corp. 10 Dec 65

|

|

315

|

N7315C

|

1017

|

27 Jun 57

|

Star of the Tagus

|

Converted to freighter, Dec 60. Sold to California Airmotive, 22 Aug 67

|

|

|

|

This early Model 049 in 1945, carried the words Trans World Airline.

|

|

The Model 1049’s fuselage was lengthened, to become the Super Constellation.

|

|

This Model 1049G "Super G" at Kansas City in lwa. It Has been restorea by the Save A Connie group of devotees, (courtesy Pete Barrett)

|

|

Ultimate development was the Model 1649, Starliner called the “Jetstream Startiner” by T. W.A.

|

|

This Model 749A (N6019C Star of Minnesota,) at Taif, Saudi Arabia (where T. W.A. was advising the national airline) on the high desert sand, (courtesy Stephen Geronimo)

|

|

Engines

|

Pratt & Whitney JT8D-9 (14,000 lb) x 3

|

Length

|

153 feet

|

|

MGT0W

|

165,000-185,000 lb

|

Span

|

108 feet

|

|

Range

|

1,700 miles

|

Height

|

34 feet

|

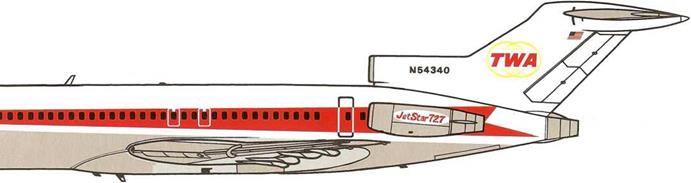

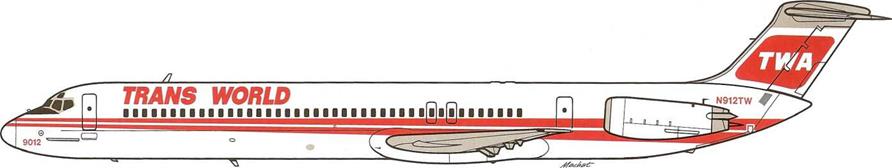

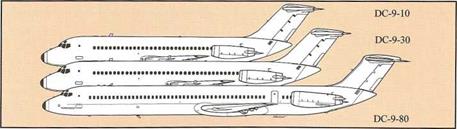

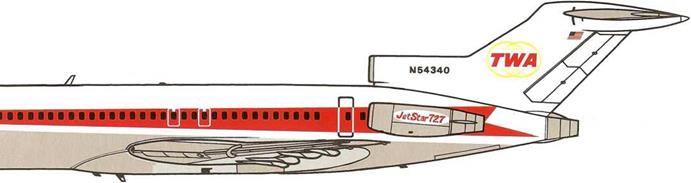

Tri-Jet Development Tri-Jet Development

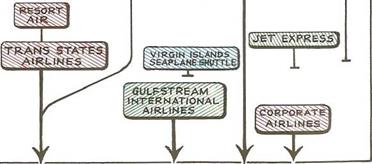

Continuing its competitive efforts over the more densely travelled domestic air routes, T. W.A. augmented its fleet of Boeing 727 tri-jets, as well as increasing its fleet of DC-9 twins. Its first 727s had started service in 1964 (see page 75) and in March 1968 the fleet was augmented by a further consignment of “stretched” versions, the Boeing 727-200 series. The inaugural -200 service had been made over the 1,100-mile New York-Miami route by a Northeast Airlines “Yellowbird.” While lacking the range of the 707, it was about the same size, and, short of nonstop coast-to-coast routes, could operate between almost any city pair in the United States.

For many years, the Boeing 727 was the most successful commercial jet airliner on the market. A total of 1,832 Boeing 727s of all types was built, a record that stood until the Boeing 737 twin-jet series overhauled it. T. W.A. had 92 of both 727 series, but showed a preference for the Douglas twins, augmenting its fleet especially when it absorbed Ozark Air Lines (page 91).

|

|

|

|

|

Technical Notes

The sub-title of this book emphasizes that this story of T. W. A. places much importance on the aircraft that it flew. As the final text went to the printer, there have been more than 1,250 of them. The Paladwr team has tried to identify and document every single one, with all the necessary details that constitute an accurate fleet record.

One of T. W.A.’s own pilots, Felix Usis ПІ, whose interests include photography and the study of ancient history (thanks partly to layovers in Cairo), devoted many hours of computer time into the preparation of the lists, drawing upon the airline’s own engineering records and, for the earlier aircraft types (long before his time) the results of research done by such historians as Ed Betts, Bill Larkins, Richard Allen, and Edward Peck. Felix supplemented his official records with additional data gleaned from various sources, including some that were not entered into the ledgers at Kansas City and St. Louis.

These lists were then meticulously checked and carefully edited by John Wegg, author and editor-publisher of Airways magazine. John is one of the world’s leading authorities on such data, and (as the saying goes) “the editor’s decision is final.” If such a presumption can be forgiven, we hope that this book will serve as a permanent and definitive reference source of all the aircraft that have flown the routes of one of the world’s great airlines.

The fleet listings are supplemented, where appropriate, with tabulations that could answer readers’ questions about the subtler differences between the variants and sub-types of some airliners. The manufacturer’s serial number (MSN) is preferred to the term constructor’s number (c/n), as in previous Paladwr Press books. Before 1949, registration numbers were NC or NX for commercial or experimental aircraft, respectively. The single N was used thereafter, and airliners already registered were re-registered when time and opportunity permitted.

Complementing the listings and data blocks with some technical observations, artist Mike Machat has added some useful “artist’s notes” — commentaries on special features, in those cases where T. W.A.’s aircraft may have differed slightly from others of the same family.

Acknowledgements

1 hope that readers will excuse any inadvertent omissions in this customary tribute to all the folks, most of them T. W. A. veterans, who have helped me to write this book. The personal recollections of old-timers have fitted in neatly with the other inputs from various sources, official and otherwise. They have added life to the factual record, and have helped this author to reflect the personality of the airline and to appreciate the tremendous depth of loyalty that has carried them through thick and thin.

Among the printed sources, pride of place must go to Legacy of Leadership, which appears at a quick glance to be another pilots’ album of nostalgia; but on closer inspection reveals a great deal more. This is because it was compiled by a great team: Ed Betts, Dan McGrogan, and Syd Albright. I first met Syd in 1965, when visiting Western Air Lines, and he will be pleased to know that the photographs that he dug up, and the reminiscences he shared, have been recalled 35 years later. To all T. W.A. pilots, Ed is almost legendary as their historian, while Dan edited that book into shape. Ozark Airlines — Contrails was a similar compilation, obviously a labor of love by an anonymous group of Ozarkians. TWA by George Cearley, an admirable scrapbook of airline memorabilia, has also been most useful.

Most of the T. W.A. collection of photographs evaporated during the troubled times of Chapter 11-threatened 1980s, but many were either rescued or duplicated by collectors and employees. Roger Bentley’s and Jon Proctor’s collections were especially valuable, and complemented my own. They were punctuated by key contributions from Felix Usis III (including the eye-catcher on the back dust-jacket), Roger Bentley, John Malandro (master navigator), Pete Barrett and Ona Gieschen (Save-A-Connie), Bernice de Garmo (daughter-inlaw of one of the Four Horsemen), Steve Geronimo, Constance Walker, and Terry Van Dyke.

As mentioned above, countless T. W.A.-ers have been kind enough to offer contributions, and I have included as many of them as possible. They have included Andy Anderson (who flew the Stratoliner, unheated and unpressurized, during the War), Barry Craig (who tried to sponsor this very book 12 years ago), Bernice and Richard deGarmo, Tom Donahue, Lawrence Dooling, Clark Fisher, Bill Halliday, Chris Hargreaves, Gordon Hargis, F. A.Harland, Russ Hazelton, Myra Hendricks, Keith Horton, John Leamon, Henry Lotito (who flew The Thing), the aforesaid navigator, John Malandro, T. W. Meredith, John Morelli, Orville Olson, Norman Parmet, Neil Poppe, Tom Roberts, Frank Smith, Marc Spiegel, Michael Swift, Тепу Van Dyke (who helped the cows on their way), Constance Walker (whose late husband founded the Conquistadores), Susan. Warren, and Claudia Woeber.

I must not forget Jim Brown, who was the initial catalyst between T. W.A. and Paladwr Press, and Donna Knobbe, who took care of many of my needs. Above all, I thank Mark Abels, who was most generous in his Foreword, assisted tremendously in the review and fact-checking processes, and opened the doors to many valuable sources of T. W.A. lore. Together we share a respect for the English language which I hope has survived my efforts and his scrutiny without leaving too many scars.

Index

Notes: P = photograph;

T = tabulation; FL = fleet list;

N1 = map; MM = Machat drawing Major entries and "Machats" are in bold type

The maps and Machat drawings are also listed in the Contents, page 5

Adamson, Gary, founds Midwest Airlines, 100 ADF (Automatic Direction Finder), ploce in history, 49 Aero-car, used on TAT. air-rail service, 24, 24P, 25P Aero Corporation of Californio, 18,18P Aeromorine, pioneer airline, 8 Aerovias Brasil, T. WA affiliation, 59T Aigle Azur, French airline, buys Stratoliners, 47 Airbus A318, ordered, 104 Air Commerce Act, 1926,8 Air Express, Inc, flies express services, 37 Air Midwest, purchased by Trans State, 100 Airline Deregulation Act, 82,90 Alderman, Ralph, navigator, 49P Alexander Eaglerock, Standard Air Lines aircraft, 18P "Ambassador" service, 64 American Airlines Claim as first airline, 8 Formation, ЗО, 30M Orders Convairliner, 60

American Export Airlines, formation, Atlantic competitor, 50

American Overseas Airlines (A. O.A.), first trans-Atlantic postwar

commercial flight, 50

Army Air Corps, carries the mail, 32

Arnold, General "Hap," greets Hughes 1944,52

Atlantic Service, 50

ATR-42, commuter airline, 101ММ, 101P

ВАС – One-Eleven, competitor to DC-9,75

Bach tii-motor, West Coast aircraft, 19P

Ball, Clifford, CAM 11,8T,8M

"Bamboo Bomber," Ozark Airlines (1943), 92

Bonk of America, lends to Hughes, 73

Beech 17D Staggerwing, Ozark Airlines (1943), 92,92P, 92FL

Betts, Ed, airline historian, 26

Black-McKellor Air Mail Act, 1934,33

Boeing Air Transport, Wins air mail contract, 9,30

Boeing 40, W. A.E. aircraft, 20P,22P,22FL

Boeing 80A, United Air Unes, 30P

Boeing 95, W. A.E. aircraft, 1 IP, 20R 22P, 22FL

Boeing 204, W. A.E. aircraft, 16,16FL

Boeing 247, worid’s first modern airliner, 32,32P

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, Tested by T. W.A. 46,46FL

Boeing 2707 SST, 74,74MM

Boeing 307 Stratoliner

First pressurized airliner, 44-45, 44P, 45MM, 45FL war effort, 46,46P, 47,47P Retired, sold, used in Vietnam,47 Compared to DC-4, Constellation, 51T Boeing 367-80,65 Boeing 707

Dominates air routes, 1958, 59 T. W.A. order, Entry into service with one aircraft, 64 Full description (-100), 65,65MM, 65P, 66P, 66FL Full description (-300), 69,69MM, 68 FL Symbolizes new его, 67P, Last T. WA. flight, 89 Boeing 717, Ordered, 104 Full description, 105,105MM, 105FL, 105P Boeing 720,69,64P, 68FL Boeing 727

Full description (-100), 75, 75MM, 75P, 76FL Full description (-200), 81,81MM, 80P, 81P, 8)FL Boeing 747

Project launched, T. WA service, 82 Full description (-100 series) 83,83MM, 83P,84P, 82FL

Index

De Havilland DH-4B, W. A.E. aircraft, 11,11FL De Havillond Comet 4 First jet airliner, 1958, 59,65 De Havilland DH-121 Trident, 75 De Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter With Ozark Air Ones, 98 Delta Air Ones Claim as first airline, 8 First order for DC-9,77 Denver Case, CAB. Route case, 64 Dickenson, Diaries, CAM 9,8T,8M Doolittle, Jimmy, returns home with T. WA Douglas M-2 (and ЛИ), WAE. aircraft, 11,11MM, 11 FI, 12P, 13P.20P

Douglas 0-38, flies Army Air Corps moil sendee, 32P Douglas B-7 bomber, flies Army Air Corps mail service, 32P Douglas DC-1

Historic prototype, 32P, 33, ЗЗР, 34P Brief history, 35 Brief description, 41

Comparison with other Douglas twins, 41MM Douglas DC-2,34P

Full description, 35, 35MM, 35FL, 35P,

Fuselage comparison with DC-3 (chart), 39 Comparison with other Douglas twins, 4ШМ Douglas DC-3

Development from DC-2,38 T. W.A. introduction (DST), 38,39MM, 39-40FL Fuselage comparison with DC-2 (chart), 39 Comparison with other Douglas twins, 4ШМ End of service, 60 Compared to post-wor airliners, 63T Ozork Air Lines (Challenger 250), 93,93MM, 93FL, 92P Freighter services, inc. wartime, 106,106P Douglas DST First version of DC-3,38 T. WA. introduction, 38,38-39FL Comparison with other Douglas twins, 41 MM Airport scene, 1930s, 42P Douglas C-47, military variant of the DC-3 Used by T. WA 38,40FL Comparison with other Douglas twins, 41 MM Douglas C-49 and C-53, military DC-3, used by T. WA, 40FL Douglas C-54

Introduction and testing, 46,46FI Delivery to T. WA, 50 Opens post-war Atlantic services, 106 First international height service, 106, 106P Douglas DC-4

Design specified by airlines, 46 Fleet list, 50T First alkargo service, 50 Entry into T. WA service, 50,51P Full description, 51,51MM Compared to Boeing 307, Constellation, 51T Douglas DC-9,76P(-31)

Ordered, 75

Fleet lists (-51,-14,-32), 76-77 DC-9-14, full description, 77,77MM, 77P DC-9-80 (see MD-80)

DC-9-30 (Ozork), 96-97,97MM, 97P, 98FL Eagle Nest Flight Center, Albuquerque, 46 Earhort, christens Ford Tr-Motor, 109P Eastern Airlines

Operates Curtiss Condor T-32,31 Chooses Martin 404,61 Economy Class, service introduced, 64 Embraer EMB145, commuter airliner, 100P Engineers

Maintain first Boeing 707,64 England-Australia Air Race, publicizes DC-2.38 Equitable Life, insurance giant Finances Boeing 707, 64 Lends to Hughes, sets up voting trust, 73 Erickson, Jeffrey, president of T. WA, 104

Ethiopian Airlines, T. W.A. affiliation, 59T

Eton Corporation, formation of T. W.A., 28

ETOPS, operations approved, 88

Fairbanks, Douglas, Jr., at T. A.T. inaugural, 24P

Fairchild C-82, full description, 56,56MM, 56P

Fairchild FH-227B (Ozark), 95,95MM, 95P, 95FL

Fairchild Metro III, with Midway/Ozark, 98,98P, 100MM

Farley, James A., Postmaster Gen, restores air mail contracts, 32

"Fashion archive," uniform collection by Clipped Wings, 48

Firestone, Harvey, at TAT. inaugural, 24

Fischer, Gerhardt, develops first radio compass, 14

Fitzgerald, Joseph, president, Ozork, 94

Flight Engineers, overtaken by technology, 49

Flint, Perry, comments on T. WA’s survival, 104

Florida Airways Corp., CAM 10,8T, 8M

Fokker F-7A (F-VII)

WAE. Aircraft, 14FL Standard Air lines, 18P West Coast Air Transport, 19P

Fokker F-10/10A, WAE. aircraft, 15,14FL, 15MM, 15P, 20P

Fokker F-14, WAE. aircraft, 20P, 22P

Fokker F-32,21,21FL, 21P,21MM

Fokker Universal, Standard Air Lines aircraft, 18P

Fokker F-27 (Ozark), 94-95,95P,95Fl

Ford, Edsel

Takes interest in Stout aircraft, 23 At TAT. inaugural, 24 Ford, Henry, at T. A.T. inaugural, 24P Ford Motor Company CAM 6 and 7,8T,8M Establishes airline, 23 Ford 4-AT Tri-Motor Maddux Air Lines, 26,26P, 26FL Full description, 27, 27MM Comparison with 5-AT, 27T Ford 5-AT Tri-Motor Full description, 23,23MM, 23FL T. A.T. transcontinental inaugural, 24-25,109P Maddux Air Lines, 26FL Master plan for T. WA, 28,29P Floatplane, 44P Comparison with 4-AT, 27T Used for freight services, 106P Fortune, magazine, comments on Hughes departure, 73 "Four Horsemen," Western’s pioneer pilots, 10,1 OP Freight services, reviewed, 106 Frye, Jock

President of Standard Airlines, 18,18P

Pictured with Fokker F-32,21P

At TAT. inaugural, 24P, At Port Columbus, 25P

Career with T. WA, ЗО, 29P

Sponsors Douglas DC-1,32, ("Jock Frye letter") 33

Breaks transcontinental speed record, 33P

Partner with Howard Hughes, 42P

Flies prototype Constellation, Burbank-New York, 1944, 52,

52P, 108P

Problems with Hughes, resigns, 64 First president of los Conquistodores del Cielo, 108 Gabor, Eva and Zso Zsa, fly by T. W.A., 109P Gann, Harry, ace photographer, 12 General Ait Freight, Ford Motor, 106 Gitner, Gerald, chairman of T. WA, 104 Global affiliations, 59

GPS (Global Positioning System), aid to navigation, 49 Grace, Thomas L., president, Ozork Air Lines, 94, 94P Graham, Maurie, one of Four Horsemen, 10P Grand Canyon Airlines (1935), 98,98M Grant, Cary, flies with T. W.A., 109P Gregory, T. E.C., pictured with Fokker F-32,21P Guggenheim, Daniel, promotes Model Airway, 14 Guggenheim Fund, 14,15

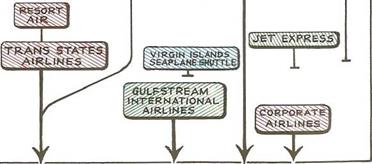

Gulfstream International, commuter airline, 100,101M Hall, Joel, founds Chautauqua Airlines, 100 Holliday, Bill, comments on post-war DC-3 services, 60 Hamilton, Laddie

Founds Ozark Airlines (1943), 92 Resigns, 94

Hamilton, Walter, Standard Air Unes, 18 Hanshue, Harris ‘Pop’

Promotes Western Air Express, 9,9P

Acquires Pacific Marine Airways, 16 Acquires Colorado Airways, 17 Acquires Standard Air Lines, 18,20 Builds W. A.E. network, 20,20M Founds Mid-Continent Air Express, 20 Pictured with Fokker F-32,21P First president of T. WA, 22,22R 28 Harland, Francis, navigator, 49 Harmon Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Hart, George, navigator, tragic death, 49 Hawaii Route Case, 82 Hawaiian Airlines, T. WA. affiliation, 59T Heathrow Airport, London, last T. WA. flight, 102 Hepburn, Audrey, flies by T. WA, 109P Hertz, John, part-owner of T. W.A., 42 Hicks, HA, member of Ford design team, 23 Hilton Hotels, purchased by T. WA, 82,90 Hiscock, Thorp, communications specialist, 14 Hoover, Herbert, Jr., WAE. communications specialist, 13P, 14 Hope, Bob, flies with T. WA, 109P Hostesses, memories, 48 Howard, William, chairman of T. WA, 104 Howell IV, Charles, founds Corporate Airlines, 100 Hughes, Howard

Brief biography, 42,42P; Buys T. WA stock 42

Break transcontinental speed record,42

Role in Atlantic service development, 50

Flies prototype Constellation, Burbank-New York, 1944,52,

52P, 108P

Interest in Bristol Britannia, 59 Prefers Martin 202 v. Convair 240, 61 Problems with Jack Frye, 64 Orders Boeing 707s and Convair 880s, 64 Problems with Convair 880,71 Surrenders ownership, 73 Icahn, Carl

Career background, takes over T. WA, 91,91P Purchases Ozark Air Ones, 91 Establishes Trans World Express, 101 Career with T. WA, and departure, 102 Agrees to method of debt payment, 104 In-Flight Movies, T. WA first, 91 INS (Inertial Navigation System) death-knell for navigators, 49 Interconf. Division (ICD), T. WA wortime operation, 46, 46M Intercontinental Hotels, acquired by T. WA, 90 Inter Urban Groin Belt Route, Parks Air Transport, 92 Iranian Airways, T. WA affiliation, 59T Irving trust, lends to Hughes, 90 James, Charles "Jimmy"

One of Four Horsemen, 1 OP, 11P With Hoover, Jr., 13P Jet Express, commuter airiine,100 Jetstream, commuter airline (see BAe Jetstream)

Jetstream, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57 Jones, Floyd, founds Ozark Airlines, 92 Jones, Jesse, Sea. of Commerce, greets Hughes and Frye, 108 Joseph, Anthony F., founds Colorado Airways, 17 Kansas Gly Overhaul and Maintenance Bose, 107, 107P Fairfax airport flooded, 108P Kellett, autogyro, 1938,101 "Kelly" Air Mail Act, 1925,8 Kelly, Fred

One of Four Horsemen, 9P, 10P With Hoover, Jr., 13P

Kerkorian, Kirk, intervenes in bid for routes, 102 Keys, Clement, defines importance of ground service, 107 K. L.M. Dutch airline, DC-2 in England-Australia Air Race, 38 Koppen, Otto, member of Ford design team, 23 Kreusi, Geoffrey, develops first radio compass, 14 Larkins, Bill, airline historian, 26 Lee, John, member of Ford design team, 23 Lehman Brothers, part-owner of T. W.A., 42 Ughted Airway Ends rail-air service, 28 Place in history, 49 Lindbergh, Charles Promotes aviation, 14,107 Technical adviser to TAT., 24,24P Flies first Maddux flight, 26, 27,27P

Plans Т. А.Т. route, 28-29,29P Approves Douglas DC-1 design, 32 Influence of 1927 flight, 52 Linee Aeree Italians (L. A.I.), T. W.A. affiliation, 59T Uttlewood, Bill, recommends DC-3 design, 38 Lockheed Air Express, W. A.E. aircraft, 22 Lockheed Altair, 37FL Lockheed Vega, 37,37MM, 37FL, 37P Lockheed Orion, 37,37MM, 37FL, 37P Lockheed 14, Hughes’s round-the-wodd flight, 42 Lockheed 18 Lodestar, 50FL Lock^.,4 (Si? ..onsteiiation (and 749), 58P Compared to Boeing 307, DC-4,51T Over New York, 52P Full description, 53,53MM.53P Full fleet list, 54FL

Commentary, 59, models compared, 59T Compared to post-war airliners, 63T Lockheed 649, T. W.A. order cancelled, 59T Lockheed Super-Constellation 1049G (and 1049H), 58P Full fleet list, 55, 55AAM Commentary, 59, models compared, 59T Lockheed L-l 649A Starliner Full description, fleet list, 57, 57ЛШ, 57FL Commentary, 59, models compared, 59T Lockheed L-l Oil TriStar Full description, 87,87MM, 87P, 86P Fleet list, 86FL

L-l 011 variants compared, 87T Loening C2H Air Yacht, W. A.E. aircraft, 16P, 16FL Loewy, Raymond, designs new cheatline, 65 Lorenzo, Frank, offeers to buy T. WA, 91 Lykins, Don, flies Douglas M-2 to Washington, 12 McDonnell Douglas DC-9-82 (ММ2)

Full description, 79,79MM, 79,78R 79P, 78FL Enters T. W.A. service, 89 Ozark Air Lines, 96,97P,97FL McDonnell Douglas MD-95 (see Boeing 717)

McNary-Watres Act, 1930, 32

Maddux, Jack L., founds Maddux Air Lines, 26-27, 26P, 27P

Maddux Air Lines, 26-27

Maiden Dearborn, Stout 2-АЇ aircraft, 23

Molandro, John, navigator, 49

Marquette Air Lines, 43, 43M

Martin 202 (and 202A)

Replaces pre-war types, 47, 60, 60P Problems, 61 Preferred by Hughes, 61 Fleet list, 62FL

Compared to post-war airliners, 63T Martin 404

Full description, 63,63MM, 60P Chosen by Hughes and Rickenbacker, 61,61P Fleet list, 62-63FL Compared to post-war aidiners, 63T Ozark Air Unes, 94,94MM, 94P, 94FL Mayo, William B., directs design of Ford Tri-Motor, 23 Metro Airlines Northeast, commuter airline, 100 Metropolitan Life, sets up voting trust, 73 Mid-Continent Air Express, founded by Honshue, 20,20M Midwest Airlines

Associtoted with Ozark Air lines, 98.98P Model Airway, The, 14,14M Mohawk Airlines, trades planes with Ozork, 94 Monroe, Marilyn, flies by T. WA, 109P Moseley, Major C. C, V. P. Operations, WAE., 10P National Air and Space Museum Preserves Douglas M-4,11,12 Receives Northrop Alpha, 36 Will have Boeing 307,45 National Air Transport CAM 3,8T, 8M

Component of United Air Unes formation, 30 Navigation, history reviewed, 49 New England and Western Tpt, flies Ford floatplane, 44P New York Airways, 101 New York Helicopter, 101,101P Northrop Alpha, 36,36P.36FL Northrop Delta, 36

Northrop Gamma

Used by Tommy Tomlinson for high-altitude research, 36P, 36FL, 38,44 Northwest Airways CAM 9,8T,8M

Problems with Martin 202,61 "Ontos," (Fairchild C-82), 56 Ozork Airlines (1943), 92 Ozark Air Unes, 92-97

Begins operations, 92,92P; Map series, 96M Twin Otter service to Meigs Field, 98 Pacific Air Transport CAM 8Д8М

Component of United Air Unes formation, 30 Pacific Marine Airways, route to Avalon, 16,16M, 20M Pacific Route Case, 82 Pon American Airways Use of flying boats, 49 First Constellation service, 50 Challenged on round-theworid service, 64 Orders 707s and DC-8s, 64, Orders 747,82 Requires more range, 84 Porks Air Transport, 92

Parks, Oliver L., founds Porks Air Transport, 92

Patterson, W. R. Pat," president, United Air Unes, 30

Pennsylvania Railroad, participates in formation of T. A.T. 24-25

Philippine Air Unes, T. W.A. affiliation, 59T

Pickford, Mary, at T. A.T. inaugural, 24P

Pierson, Warren Lee, president, 1948, and 1957,64,73, 90P

Pilgrim 100A, American Airlines, 30P

Piper Twinair, 98,98M

Pittsburgh Aviation Industries Corp. (P. A.I. C.), participant in formation of T. W.A., 28

Pogue, L. Welch, chairman, C. A.B., initiates local service, 92 Polar Service, 64

Port Columbus, transfer station on T. A.T. transcontinental, 25 Portair, T. A.T. air-rail transfer station, 24,24P Ransome, J. Dawson, founds airline 101 Raymond, Arthur, designs Douglas DC-1,32 Redman, Ben, first possenger, 6P Resort Air, first name of Trans State, 99 Rhodes, Kathryn, first chief hostess, 48P Richter, Paul, Jr.

Treasurer, Standord Air Unes, 18 With TAT., 29P, Resigns, with Frye, 64 Rickenbacker, Eddie, joins Hughes in choosing Martin 404,61 Robbins, R. W.

President of T. WA, 28.29P Furloughs T. WA staff, 32 Robertson Aircraft Corp.

CAM 2,8T, 8M

Rockne, Knute, crash victim, 15 Rogers, Will, first passenger, 108,108P Roshkind, Allan, designs Martin 202,60 Roosevelt, President Cancels oir mail contracts, 32 Flies with T. WA during v/or, 46P Round-the-wodd service, 50M, 64 Rummel, Bob, tests Martin 202 ond Convair 240,61 Russell, Jane, flies with T. WA, 109P SAAB 340, commuter airliner, 99MM Ryan №1, Colorado Airways aircraft, 17P, 17FL Saudi Arabian Airlines, T. WA affiliation, 59T "SavetfConnie" organization, preserves Constellation, 59 Scheduled Air Taxi service, 98 "Secret Weapon," Constellation description, 52 Seven States Area Case, 94 "Shotgun Marriage," merger of WAE. ond T. A.T., 22 Shroeder, Major, Ford test pilot, 23 Sikorsky S-38A, W. A.E. Aircraft, 16P, 16FL Silver Wings, hostess retirement group, 48 Smith, C. R.

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57

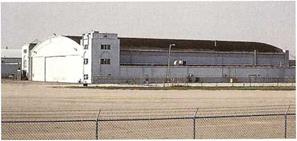

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.

Ray Dunn presides over a morning hour-long briefing in 1962 at the Mid Continent International Airport, where trouble-shooting was refined by long distance telephonic communication throughout the TWA system.

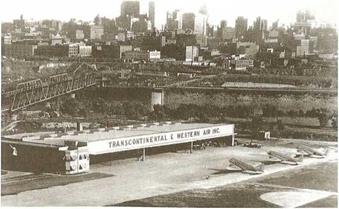

The building is still there. As one of the very few—and undoubtedly one of the most historically significant— 70-year-old architectural survivals of the formative years of air transport in the United States, it should be listed as an Historic Monument.

The building is still there. As one of the very few—and undoubtedly one of the most historically significant— 70-year-old architectural survivals of the formative years of air transport in the United States, it should be listed as an Historic Monument.

![Secret Weapon Подпись: Fleet No. Regn. MSN Delivery Date Name Disposal and Remarks Model 749A (Delivery 749A-79-52) 801 N6001C 2633 24 Mar 50 Star of New Jersey AT 802 N6002C 2634 11 Apr 50 Star of Kansas Renamed Star of Crete. Sold to C.E.Bush Aviation, 10 Dec 65 803 N6003C 2635 24 Apr 50 Star of Texas Renamed Star of America, AT 804 N6004C 2636 2 May 50 Star of Maryland Crashed and destroyed by fire near Wadi Natrun (50 miles north of Cairo, Egypt), 31 Aug 50 805 N6005C 2637 19 May 50 Star of New York AT 806 N6006C 2639 29 Jun 50 Star of Pennsylvania AT 807 N6007C 2643 18 Aug 50 Star of Ohio AT 808 N6008C 2644 7 Sep 50 Star of Indiana AT 809 N6009C 2645 11 Sep 50 Star of Michigan Sold lo AVIANCA, 10 Осі 59 810 N6010C 2646 20 Sep 50 Star of Illinois Renamed Star of Germany, AT 811 N6011C 2647 10 0(150 Star of Missouri AT 812 N6012C 2648 13 Oct 50 Star of Massachusetts Renamed Star of Spain, Sold to Federal Administration, 20 Jul 62 813 N6013C 2649 24 Oct 50 Star of New Mexico Renamed Star of Majorca, AT 814 N6014C 2650 3 Nov 50 Star of Delaware Sold to Central American Airways, 5 Oct 67 815 N6015C 2651 17 Nov 50 Star of Arizona Sold to C.E.Bush, 23 Mar 66. Repossessed 1967. AT [6 May 63] 816 N6016C 2654 12 Dec 50 Star of California Sold to Federal Aviation Administration 817 N6017C 2655 21 Dec 50 Star of the District of Columbia Leased to Pacific Northern Airlines, 17 Aug 61. Sold to Connie Air Leasing, 24 Nov 61 818 N6018C 2656 29 Dec 50 Star of Nevada AT 819 N6019C 2657 17 Jan 51 Star of Minnesota AT 820 N6020C 2658 25 Jan 51 Star of Kentucky AT* 821 N6021C 2667 17 Apr 51 Star of West Virginia AT 822 N6022C 2668 30 Apr 51 Star of Virginia Sold to Pacific Northern Airlines, 30 Jun 66 823 N6023C 2669 8 May 51 Star of Iowa AT 824 N6024C 2670 29 May 51 Star of Nebraska AT 825 N6025C 2671 Star of Colorado Fleet number and name allocated, but aircraft delivered to Hughes Tool Company. Sold to B.O.A.C, U.K.,23 Sep 54 826 N6026C 2672 29 Jun 51 Star of Connecticut AT 827 N86521 2642 1 Apr 54 Star of Oregon Delivered 12 Aug 50 to Chicago & Southern Airlines as City of Houston, then Cindad Trujillo. To Delta Air Lines, 1 May 53, with merger. Converted from Model 649A to 749A. Name later changed to Star of Colombo. AT 828 N86535 2673 20 Apr 54 Star of Wisconsin Delivered 18 May 51 to Chicago & Southern Airlines. To Della Air Lines, 1 May 53, with merger. Converted from Model 649A to 749A. Renamed Star of Corsica, then Star of Basra. AT 829 N86552 2653 1 Jun 54 Star of Washington Delivered 27 Sep 50 to Chicago & Southern Airlines. To Delta Air Lines, 1 May 53, with merger. Converted from Model 649A to 749A. Renamed Star of Madeira, then Star of Dhahran. AT](/img/1243/image238_0.gif)

Tri-Jet Development

Tri-Jet Development

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57

President, American Aidines, 30 Claims for DC-3 profitability, 38 Southern Air Transport, component of American Airways, 30 "Spoils Conferences," 32 Sportsman’s Trophy, won by Howard Hughes, 42 Standard Air Unes, pioneer airline in the v/esxt, 18,18M, 20M Stadiner, name for Lockheed L-1649A, 57