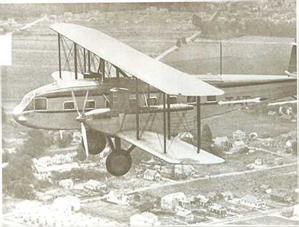

Curtiss Condor CO

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

![]()

The Condor

The Curtiss Condor was the last large biplane built in the United States. T. A.T. put it into service early in 1929, and until the Douglas DC-2 came along, it supplemented the Fords on routes where the traffic demand was high. It was much bigger, weighing nine tons against the Ford’s six, and could carry more people with a more attractive cabin. But it was not much faster, and its life span with the United States airlines was only about three years. T. AT.’s Condor COs (also designated the Condor 18, the B-18 or the B-20) were N185H, N725K, and N726K (manufacturer’s serial numbers G-l, G-2, and G-4, respectively).

A later version, the T-32, went into service with American Airlines and Eastern Air Lines in 1934 as a much-publicized sleeper transport; but by all accounts, the passengers did not get much sleep. The low-altitude flying tended to be a little rocky, and the segments were too short. In any case, the modern airliners would soon be outlasting the obsolescent Condor design. Biplanes were becoming a thing of the past.

|

The NlcNary-Watres Act

The spur to the spectacular growth of air transport in the United States in the early 1930s was the result of imaginative legislation, enacted after substantial persuasion by the Postmaster General, Walter F. Brown. The Third Amendment to the Air Mail Act, named after its Congressional sponsors, was approved on 29 April 1930. Its far-reaching provisions gave permanence to the contracted operators, paid them according to space offered, not by the weight of mail carried, and gave Brown powers to extend or consolidate routes to improve the system. This encouraged the airlines to invest in larger aircraft, which were more economical to operate; and gave Brown almost unlimited authority to draw the airline map as he pleased.

The "Spoils Conferences"

Things went mainly according to Brown’s plan, which was to fashion a rational system of air routes that would not suffer from the excessive fragmentation he had observed in the railroad system. No single railroad, for example, ran from coast to coast. Brown’s pressure and advice to the incumbent air mail carriers resulted in three transcontinental airlines that followed different routes, but offered opportunities for competition between the main traffic-generating areas: California and the Northeast.

But to do this, he sometimes overstepped the mark in what was perceived to be selective manipulation of the exact intentions of the Air Mail Act, and even, it was alleged, a certain degree of favoritism. This led to an investigation of the circumstances of a series of meetings that he had held with the airlines between 15 May and 9 June 1930, and which became known as the Spoils Conferences.

The Air Mail Scandal

Many of the small airlines felt that they had been by-passed deliberately; and although their case was not well documented and of doubtful legality, it was intensively publicized—so effectively, in fact, that, responding to political pressure, the Senate set up a Special Committee. Its adverse report resulted in President Roosevelt taking the unprecedented step, on 9 February 1934, of cancelling all the air mail contracts and asking the Army Air Corps to carry the mail. This it did, with remarkable success, bearing in mind the extreme difficulties of weather and inexperience with which it was faced. But some pilots were killed, mostly in training, and this led to a national outrage that forced Roosevelt to retract his decision.

A New Life

On 30 March 1934, the Post Office Department invited the airlines to submit new bids, and these were duly accepted by the new Postmaster General, James A. Farley, on 20 April. During the two months during which the Army carried the mail, the airlines struggled on the best they could. Drastic measures had to be taken, as the revenues from passengers and express were insignificant compared with the mail payments—effectively a life-sustaining subsidy. In the case of T. W.A., President Richard W. Robbins sent a letter to all the staff, which began: “Effective February 28th, 1934, the entire personnel of T.& W. A. is furloughed.”

On 30 March 1934, the Post Office Department invited the airlines to submit new bids, and these were duly accepted by the new Postmaster General, James A. Farley, on 20 April. During the two months during which the Army carried the mail, the airlines struggled on the best they could. Drastic measures had to be taken, as the revenues from passengers and express were insignificant compared with the mail payments—effectively a life-sustaining subsidy. In the case of T. W.A., President Richard W. Robbins sent a letter to all the staff, which began: “Effective February 28th, 1934, the entire personnel of T.& W. A. is furloughed.”

|

|

|

Postmaster-General Walter Folger Brown was the czar of the U. S. air transport industry in the early 1930s. By awarding air mail contracts for specific routes (without which no airline could operate profitably), he laid the foundation for a nationwide airline network. |

|

|