Carl Takes Over

On 14 June 1985, one of T. W.A.’s Boeing 727s was hijacked en route from Athens to Rome. Three months later, on 26 September, many T. W.A. veterans felt that their entire airline had been hijacked by Carl Icahn. On that day, he took over control (see page 91), accepted wage concessions already agreed by the unions, and appeared to compensate them in a profit-sharing plan, with the promise of setting up an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP). Though he seemed optimistic about the airline’s prospects under his control, there was a catch: there were few profits to share.

A Promising Start

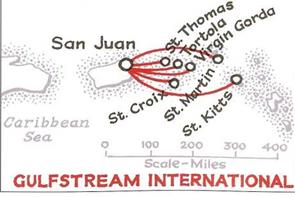

Carl seemed to start well. T. W.A. moved strongly into the Caribbean, expanding service from New York and St. Louis to several resort destinations; and in the New Year, reaching agreement for a Piedmont Airlines feed into New York. On 26 February 1985, he asserted “to combine two losers, we hope to create one profitable carrier.” On 11 March 1986, he won a victory in the courts, when Judge Howard F. Sachs ordered the machinists back to work during a strike by 5,700 flight attendants who had walked off the job less than a week earlier.

The Clouds Darken

But T. W.A.’s problems went deeper, and were exacerbated in the months to come. In April 1986 a terrorist bomb exploded in mid-air on an Athens-bound flight, killing 4 and wounding 9 passengers. Remembering the incident less than a year previously, the European-bound travelling public edged away from, rather than up-and-awayed with T. W.A. With diminishing returns, Icahn extracted further concessions from the pilots. The 1987 figures were no better, and the October “Black Monday” stock market mini-crash led Icahn (who held 70 percent of the stock) to delay all the previous plans for privatization by a year.

This was eventually spelled out in September 1988. Icahn and other shareholders received $20 in cash per share. Carl’s amounted to $469 million, which was $25 million more than his original investment. He also received some preferred stock. The stock had previously been held by A. C.F. Industries, described as the cornerstone of Icahn’s empire. One description of this financial juggling was very simple; “a leveraged buyout that added $1 billion in debt.” Icahn himself described T. W.A. as “not one of my most stellar investments,” a statement that strongly suggested that his interest in becoming an airline emperor like Howard Hughes was waning. He proceeded to sell off much of the airline’s assets of equipment and routes.

In 1989, he sold eleven jet aircraft and five gates at Kansas City. Early in 1990 he agreed to sell the Chicago-London route to American Airlines for $ 195 million. He threatened to sell the domestic route system if the pilots did not agree to more concessions. He sold and then leased back ten more aircraft. By the summer of 1990, the situation had reached crisis level — $3 billion debt, no less. The unions proposed a restructuring plan, for Icahn to swap most of his now 90 percent stake for money owed, and thus reduce the debt. He responded by proposing the termination of unprofitable routes (this could have been most of the system at that time) and announced a two-tier salaries plan. In October, 450 staff were furloughed, and service terminated at many points in the system.

Selling The Farm

Worse was yet to come. It was a time when other airlines were also facing disaster. On 11 November 1990, Icahn offered to buy Pan American — an almost ludicrous proposal. On 12 December, American Airlines offered $445 million for all T. W.A.’s routes to London. On 21 January 1991, Icahn announced the halving of all services to Europe and furloughed 2,500 employees. Some palliatives were derived from a longterm contract with Military Airlift Command (MAC) and the D. O.T. award of a route to Moscow and Leningrad. But this was immediately offset by the effect of the Gulf War, which seriously eroded txrans-Atlantic traffic for all airlines. T. W.A. had always depended upon European and Middle Eastern routes as its best money-earner. Now the political fates were weighted heavily against them.

“Cheer up” they said, “things could be worse. So I cheered up. And they were worse.” And so it went with T. W.A. On 14 March 1991, the blow came. The D. O.T. approved the sale of routes to American, but restricted the sale to New York-London, Los Angeles-London, and Boston-London. Icahn protested strongly: “This order could well become a disaster for T. W.A.”

This inspired financier Kirk Kerkorian to step into the ring; but his intervention only led to American agreeing to buy the three routes for the full price for the five that had been included in the original offer.

Goodbye to Heathrow

No single event in T. W.A.’s history could have epitomised its decline and fall from the heights of the world airline hierarchy than its departure from London’s Heathrow Airport, the busiest international airport in the world, the biggest gateway to Europe, the jewel in every trans-Atlantic airline’s crown.

On 1 July 1991, the last T. W.A. flight, a Boeing 747, took off, accompanied by a multiple fire-truck hose salute. As the aircraft was permitted a sentimental fly-by, the Heathrow tower called “it was nice knowing you.” T. W.A. transferred its London terminus to Gatwick. The effect was a reprieve from imminent bankruptcy, but this was a case of merely putting off the evil day.

Chapter Eleven

The acquisition of Pan Ant Express on 4 December 1991 (see page 101) was a momentary diversion from far more serious considerations for T. W.A. On 31 January 1992, the airline filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Carl Icahn called it “pre-planned,” a euphemism that can be compared with second-hand cars being called “pre-owned.” T. W.A. was in a bad way. Its total debt of $1.7 billion was more than its net worth. By the summer it was losing $2 million a day. Opening a New York-Moscow service on 17 March did not exactly reverse the balance sheet.

For the employees, the month of August was Make or Break. On 14 August, the flight attendants agreed to take pay cuts; on 24 August (at 5 a. m.) the Machinists’ Union followed suit. On 26 August, the pilots agreed, with the condition that Icahn would lend the airline $200 million and forgive $170 million owed. In exchange for the collective concessions, amounting to about 15% in value, all workers had 45% of the equity of a reorganized T. W.A.

On 15 November 1992, Carl Icahn agreed to the terms, and in a key decision, on 6 December, the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation, the largest creditor, agreed also. Missouri Senator Jack Danforth described the events thus: “I don’t believe in my lifetime that I have seen people who believe so strongly in their company.” The confirmation and justification for all their sacrifices came on 8 January 1993, when Carl Icahn relinquished all control, interest, and direction of T. W.A. Ten months later, on 3 November, T. W.A. emerged from bankruptcy.

This was a triumph for unqualified loyalty and dedication. It was in striking contrast with what happened at Eastern Air Lines in Miami in 1990. When Eastern’s union leaders learned that Frank Lorenzo had finally said “enough is enough,” and closed down the airline, they celebrated with champagne and shouts of “we’ve won.” And 30,000 employees lost their jobs and their living. In T. W.A.’s case, the employees remained loyal, made a deal, and kept their jobs. They made a major contribution towards the survival of one of the world’s great airlines. They really did win.

BOEIMIS 757 FLEET LIST

BOEIMIS 757 FLEET LIST

All aircraft listed are Boeing 757-231s, except the leased

aircraft (lessors indicated), which are 757-2Q8s

Boeing Takes Another Gamble

When Boeing announced the Boeing 757, almost simultaneously announcing the 767, many airline observers thought that the Seattle manufacturer, already noted for its readiness to take chances (albeit successfully) had this time gone too far. The two aircraft appeared to be aimed at markets which, if not identical, seemed to overlap. Yet there was a method in their apparent madness. When the announcements were made, in the late 1970s, the airline industry was booming, world-wide. Airlines were being selective, with many choices available, and there was an advantage in having a range of types that could meet every particular need.

The 767 was a completely new design, but the 757, originally to be a refined 727-300, was built on the same fuselage jigs as on those of previous Boeing winners, from the first 707, then the 727, and the 737. Certainly the wings and empennage

were new; but there were economies in the construction, and that permitted Boeing to sell at a very competitive price. Most important, the 757 and 767 had almost identical cockpits, which allowed a common pilot rating.

|

|

Perhaps the best application of this airliner to T. W.A.’s network was on 10 September 2000, when it opened nonstop service from Los Angeles to Washington’s downtown airport, Reagan National (formerly National). Wide-bodied aircraft (such as the Boeing 767 or the Airbuses) are not allowed there. But the airport is only ten minutes on the local subway from the business district and political quarters of the nation’s capital, a huge advantage over service to Dulles International, which is at least an hour’s taxi ride from the center, and where public transport is usually conspicuous by its absence. With its narrow-bodied 757, T. W.A. has effectively cut an hour off the Los Angeles-Washington journey.

Time to Move On

Time to Move On

33 seats • 220 mph

33 seats • 220 mph

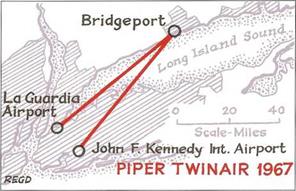

The New York Connection

The New York Connection

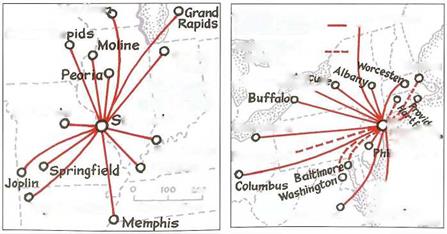

Today, T. W.A. offers many “best connections” to many more places with larger aircraft through its Express Connections throughout the northeastern States, (see also page 99)

Today, T. W.A. offers many “best connections” to many more places with larger aircraft through its Express Connections throughout the northeastern States, (see also page 99)

BOEIMIS 757 FLEET LIST

BOEIMIS 757 FLEET LIST