PROGRESS Ml-11

In the immediate aftermath of the loss of STS-107 in February 2003, NASA had asked the Russians to launch an additional, fourth, Progress in 2003. Despite having requested the extra launch, NASA was unable to offer any payment in support of it, due to the terms of the Iran Non-Proliferation Act, which forbade American companies and government departments from spending their money in countries that supported Iran’s attempts to develop nuclear power and, through that programme, nuclear weapons. The launch of the extra Progress had been delayed from November 2003 to January 29, 2004.

On that date Progress M1-11 was launched at 06: 58, and followed a standard two-day rendezvous trajectory, before docking to Zvezda’s wake at 08: 13, January 31. The Expedition-8 crew spent the next week unpacking the new arrival. Following a test-firing of the Progress’ thrusters, the crew observed a small strip of material drifting away from the station, but noted that it did not appear to represent any danger to ISS. Two weeks later the object was identified as a bolt and washer used to hold the photovoltaic arrays on Progress M1-11 in their folded position during launch. They served no purpose after the spacecraft’s arrays had been deployed. During the week ending January 31, Foale also initiated the ESA PROMISS-3 cell culture growth experiment that had been carried into space on Progress M1-11. It would be run for 30 days and the results would be returned to Earth on Soyuz TMA-3.

February began with a period of silence to mark the first anniversary of the loss of STS-107, and the unloading of Progress M1-11. The crew also began a highly toxic Japanese experiment called the Granada Crystallisation Facility. Kaleri commenced the Russian Mimtec-K protein crystal growth experiment. He also deployed the Russian Brazdoz radiation detectors inside Zvezda. On February 4, Kaleri began repairs of the Elektron oxygen generator and the Vozdukh carbon dioxide remover. A fan in the latter had begun making a loud noise and would be replaced during the following week. The international experiment programme continued throughout the next week alongside routine maintenance and exercise. During the second week of the month the crew completed the ongoing regular collection of air and swab samples from surfaces inside ISS. Progress M1-11 had been emptied by February 11, and the crew began loading the spacecraft with unwanted items. Elektron failed during the day, but Kaleri had it working again within 24 hours. It failed once more on February 16, and it took 3 days of efforts by Kaleri, with Korolev’s assistance, to put it back in action. It failed again the following day and the station’s atmosphere was topped up using oxygen from Progress M1-11.

On February 16, Korolev released details of the problem with the Soyuz TMA-3 spacecraft. It was

“… a minute pressure decay in the two helium systems that pressurise the Soyuz propellant tanks and lines… The pressure decay was first noted on system-2 when the Soyuz arrived at the station in October, and was confirmed on system-1 during a routine thruster test… Flight directors have concluded that the decay poses no concern. The decay was extremely small and there are no plans to change normal entry and landing procedures.”

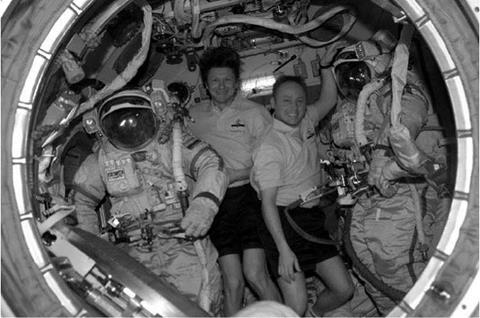

As they approached 4 months (February 18) in their occupation, Foale and Kaleri commenced early preparations for their only Stage EVA, planned for February 26. They shifted their sleep schedule to accommodate the start of the EVA. Foale also positioned the SSRMS so that its cameras and lights could offer maximum coverage of their external activities. The EVA would take place from Pirs, with both men wearing Orlan pressure suits. It would be the first EVA from ISS where all crew members were outside of the station, and no one was inside monitoring the station’s systems and choreographing the EVA against the flight plan, or operating the SSRMS to provide the best possible video coverage. Although NASA was originally unhappy about this arrangement, the Soviets/Russians had used it throughout their Salyut and Mir space station programmes.

The following week was spent preparing for the planned EVA. Both men unpacked their Orlan EVA suits and checked them over, working closely with controllers at Korolev. They also carried out another, successful, exercise that proved they could move between Pirs and Soyuz TMA-3 while wearing Orlan pressure suits, in the event that they had to abandon ISS as a result of an unexpected event occurring during the EVA, which prevented them re-entering the station.

After configuring the station for a period of non-occupation, Foale and Kaleri locked themselves inside Pirs. At 16: 17, February 26, they opened the hatch and made their way into open space, leaving ISS unoccupied. They collected their tools, secured their tethers, and made their way to the exterior of Zvezda. There, they replaced one of two cassettes of long-duration material exposure samples that were part of the Japanese Micro-Particle Capture and Space Environment Exposure Devices (MPAC/SEEDs) experiment that had been put in place, to measure micrometeoroid impacts, in October 2001. Next they installed the Russian “Matryoshka” experiment on handrails on Zvezda’s exterior. The experiment housed simulated human tissue samples, which would be used to study radiation absorption. As they completed this work Kaleri reported water droplets forming on the inside of his visor and a rise in the temperature inside his suit. It was approximately 18: 00. A few minutes later, engineers at Korolev reported problems with the cooling system in Kaleri’s suit, leading to a build-up of condensation on the inside of his helmet.

Kaleri returned to Pirs, while Foale replaced one of two cassettes of long – duration exposure material samples on Zvezda’s wake airlock housing before joining his colleague in Pirs. The hatch was closed at 20: 12, after an EVA lasting 3 hours 55 minutes. After pressurising the airlock Foale climbed out of his suit, so that he could carry out an inspection of Kaleri’s suit. During the inspection he discovered a kink in a cooling water tube. When the kink was straightened out the water began flowing freely once more. The two men re-entered ISS, which had performed flawlessly in autonomous mode throughout the EVA. American fears of leaving the station unoccupied had proved groundless. The week following the EVA began with light duties, but the crew also worked on their experiments and routine housekeeping tasks.

Progress M1-11’s thrusters were used to raise the station’s altitude on March 2. During preparations for the burn a momentary spike was observed in the electrical current reaching CMG-3. After the spike all readings returned to normal and CMG-3 continued to operate as planned. Foale had prepared Destiny’s window for the replacement of the jumper hose that had been identified as the source of the pressure leak earlier in the month. The gaps between the various panes of glass in the window were vented over the weekend to disperse condensation that had built up. On Friday March 5, a vacuum was re-established between the panes of glass in the window in advance of replacing the jumper hose. Once installed the new jumper hose was fitted with a new cover, to prevent it being knocked accidentally.

The week ending March 12 began with a three-day weekend off, after which the crew spent three days working closely with Houston to disassemble their exercise treadmill and remove the gyroscope that had malfunctioned in November 2003. They then replaced a bearing within the gyroscope before replacing the gyroscope and reassembling the treadmill. Houston monitored the first few days of treadmill use with the Vibration Isolation System re-activated, to ensure it was functioning correctly. NASA reported:

“The crew heard noises coming from the treadmill in November, which engineers determined was a failed bearing in the gyroscope that stabilises movement in the roll direction. A repair kit was sent to the station in January [on Progress M1-11] … After this week’s repair work, Foale reported the noises had stopped.”

Kaleri continued to work on the Elektron oxygen generator in Zvezda. On March 12, he began a total review of the system, to identify what items needed replacing. Following a final replenishment of oxygen from Progress M1-11, two Russian SFOG oxygen candles were burned each day in Zvezda, commencing on March 13, to supplement the oxygen supply while the Elektron repairs continued. At the end of the week Foale performed further activities while wearing the FOOT experiment to record how he used his limbs in microgravity. He also used a computer training package to familiarise himself with the Advanced Diagnostic Ultrasound in Microgravity (ADUM) experiment. Later in the flight, Foale would use the experiment to make an ultrasound examination of Kaleri. On March 14, CMG-2 in the Z-1 Truss fell off-line for 2 minutes before the emergency system restored it to correct operation. Similar failures and recoveries would occur over the next several days.

The following week Foale and Kaleri spent two days replacing a liquids unit and a water flow system in the Elektron oxygen generator. Following earlier repairs, Russian engineers had decided that air bubbles in the liquids unit had repeatedly caused the Elektron unit to shut down after only a few minutes of operation. The work on Elektron necessitated the re-scheduling of other, lower priority tasks. Following the repair the Elektron unit was activated on Saturday March 20, and performed well. It was left running and the crew stopped burning SFOGs. NASA was at pains to point out that over 100 SFOG candles remained in storage on ISS, along with two tanks of high-pressure oxygen in the Quest airlock, which could supply the crew with breathable oxygen for several months if required. On March 22 and 23, both men participated in noise level measurements. The working week ended on March 26, when Foale carried out a regular inspection of one of the two American EMUs held on the station.

As March turned to April the Expedition-8 crew began their final month onboard ISS. They completed an initial maintenance of the two Russian Orlan suits delivered to the station on Progress M1-11 in January, to replace three older Orlan suits that had been used by earlier Expedition crews. Foale completed a final session of training on the SSRMS on April 2. He used the arm’s cameras to complete an external inspection of the station. He also noted that the noise that the crew had reported earlier in the flight was repeated each time he commanded Destiny’s external

camera to pan up and down. In Russia, controllers were considering having the crew replace the fan in the Soyuz TMA-3 descent module that had failed during the journey up to the station in October. The fan assisted in maintaining the humidity inside the cabin.

American controllers successfully completed tests of the software that would control the Thermal Rotary Radiator Joints on the ITS when its installation continued, following the Shuttle’s Return to Flight. The software would be used to automatically position the cooling radiators mounted on the Truss once the station’s cooling system was activated, following the flight of STS-116.

Foale spent the last two weeks of his occupation completing the FOOT and PFMI experiments, and Kaleri changed a set of two ventilation and humidity fans in Soyuz TMA-3. They also began preparing the items that they would take back to Earth with them. During the week ending April 16, both men participated in a test of Soyuz TMA-3’s thrusters, during which controllers in Korolev noticed the same helium leak that had been monitored during the rendezvous with ISS. Korolev conducted additional tests of the helium system, which was used to pressurise the spacecraft’s propellant tanks, to time the leak rate. The crew also completed environmental sampling at various points inside ISS for return to Earth for investigation. Foale also set up the ESA HEAT experiment in the MSG in anticipation of the arrival of Soyuz TMA-4 with Dutch astronaut Andre Kuipers, who would use the experiment to see if a grooved heat pipe can be used to transfer heat from hot surfaces, such as electronics, to cold surfaces, such as radiators, in microgravity.

|

SOYUZ TMA-4 DELIVERS THE EXPEDITION-9 CREW

|

The Soyuz TMA-4/Expedition-9 crew was originally named as Commander Valeri Tokarev and Flight Engineer William McArthur. On January 12, 2004 NASA announced that McArthur had been removed from the crew for “unspecified medical reasons’’ and replaced by Leroy Chiao. Tokarev and Chiao subsequently proved incompatible as a crew, and in February 2004 they were replaced by the original Soyuz TMA-5 prime crew of Gennady Padalka and Michael Fincke, the original Expedition-10 crew. Andre Kuipers, a Dutch ESA astronaut, would continue to fly to ISS with the new crew. By the time the crew change was announced McArthur had already recovered his health, but he and Tokarev had lost too much time training, so they were named as the new Soyuz TMA-7/Expedition-12 crew.

Soyuz TMA-4 was launched at 23: 19, April 18, 2004. Docking with the nadir port on Zarya occurred at 01: 01, April 21, and following pressure checks the hatches were opened at 14:00. The three newcomers entered the station and were given a safety briefing. Padalka and Fincke would spend 6 months on the station as the Expedition-9 crew and make two Stage EVAs from Pirs. Kuipers, the second Dutch national to fly in space, would return to Earth with the Expedition-8 crew, after spending 9 days in flight. While the Expedition-9 crew began their familiarisation and hand-over period, the Expedition-8 crew exercised rigorously prior to their return to Earth. After his recovery, Kuipers would describe his feelings:

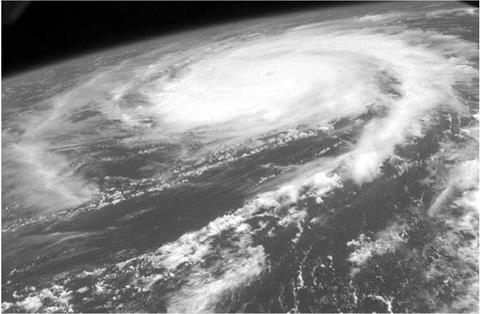

“It was amazing, better than I had ever expected. All the different colours of

Earth; such brilliance… Gliding past huge clouds, and vast expanses of water.

You see cities from above and lightning on top of clouds instead of underneath.

At times like that it hits you that you really are in space.”

Kuipers had begun his Dutch Expedition for Life Siences, Technology and Atmospheric Research (DELTA) experiment programme during the solo portion of Soyuz TMA-4’s flight, performing a package of 21 ESA experiments. He commenced his programme on ISS almost as soon as the hatches were open between the two spacecraft. On April 21, two runs of the HEAT experiment in the MGS were terminated automatically when the upper temperature limit was reached, and a third

|

Figure 44. Expedition-9: ESA astronaut, Dutchman Andre Kuipers participated in every astronaut’s favourite off-duty pastime, watching the Earth turn outside the window, during his short stay on ISS. Arriving with the Expedition-9 crew, he returned to Earth with the Expedition-8 crew. |

run of the experiment was cancelled. After troubleshooting of the experimental hardware the following day, a further four runs of shorter duration were completed before the experiment was stored in Zvezda. Kuipers suffered continual problems with some of his experiments’ hardware, including a centrifuge. Throughout the remainder of the week the Dutchman became a human subject for a number of microgravity and life science experiments. He also assisted Foale and Kaleri to prepare Soyuz TMA-3 for their return to Earth.

On April 21 the Expedition-9 crew were informed that CMG-2 had gone off-line at 16: 20, after the RPCM, a circuit breaker mounted on the S-0 ITS, had malfunctioned and cut power to the CMG. CMG-1 and CMG-2 continued to perform flawlessly and were sufficient to control the station’s attitude. Controllers in Houston began planning an unscheduled third Stage EVA, on June 10, to replace CMG-2 with a CMG held in storage on the station.

The official hand-over ceremony between the Expedition-8 and Expedition-9 crews took place in Destiny on April 26. On the same day Foale, Kaleri, and Kuipers spent several hours in Soyuz TMA-3, rehearsing their undocking and re-entry procedures. Two days later propellant was transferred from Progress M1-11 while the crew slept.

After a week-long hand-over, Foale, Kaleri, and Kuipers said farewell to Padalka and Fincke and sealed themselves in Soyuz TMA-3, preparing to return to Earth. Soyuz TMA-3 undocked at 16:52, April 28, retrofire occurred at 18: 20, with no difficulties, and the re-entry module landed at 20: 12 the same day. The Expedition-8 crew had spent 194 days 18 hours 35 minutes in space. They were just one day behind the Expedition-4 crew. Foale’s personal accumulative record stood at 374 days 11 hours 19 minutes, including his Shuttle flights and his stay on Mir. He was the first American astronaut to spend a total of over one year in space. All three men were in good health and excellent spirits following their landing. As usual, the returning Expedition crew members underwent a 45-day rehabilitation programme.

Meanwhile, NASA admitted that they would be unlikely to meet the March 6, 2005 target date for STS-114, the Return to Flight mission. One of the limiting factors remained the development of the OBSS. The OBSS would give access to most of the Shuttle’s TPS, but not all of it. It would also be strong enough to support an EVA astronaut if any repairs had to be made to a Shuttle’s damaged TPS. It was not even guaranteed that STS-114 would carry the OBSS. If it did not, then the TPS inspection would have to be made by astronauts on an EVA to inspect those areas of the orbiter that could not be seen from the flight deck windows, or with the cameras on the Shuttle’s standard RMS.

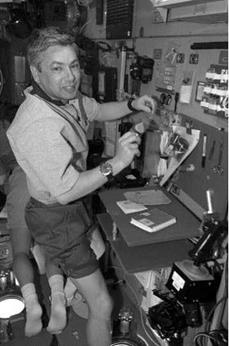

Figure 49. Expedition-10: having arrived with the Expedition-10 crew, Yuri Shargin worked on his experiment programme before returning to Earth with the Expedition-9 crew. The individual behind him is not identified.

Figure 49. Expedition-10: having arrived with the Expedition-10 crew, Yuri Shargin worked on his experiment programme before returning to Earth with the Expedition-9 crew. The individual behind him is not identified.