On the subject of the crew’s daily routine Bursch added

“It’ll basically be, wake up, get ready to go have some breakfast, read the morning mail, and have some time together, to talk about the upcoming day, what do we have planned for the day. So regular things like that, whether it’s personal hygiene or reading or getting up-to-date is going to be somewhat normal. And then there’ll be some weeks that I think the pace will definitely change.. .the pace will probably be toughest… when the Shuttle is docked, and we’re doing operations together

|

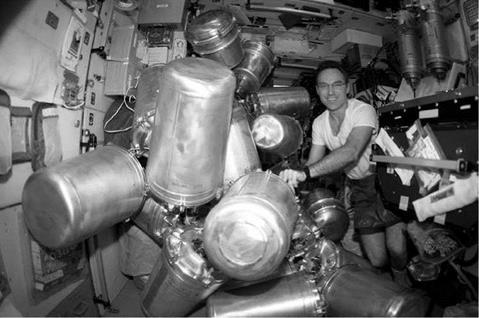

Figure 13. Expedition-4: Carl Walz works with containers of potable water inside Zvezda. |

and involving many different systems. Certainly the pace will be much slower… if the Shuttle isn’t there… So the pace is probably going to be all over the place.”

Onufreinko, Walz, and Bursch settled into their own routines in the third week of December. They activated science experiments and unloaded Progress Ml-7 as well as the equipment carried to ISS on STS-108. The Expedition’s cellular experiments, begun on December 15, were completed after 12 days. On December 19, the crew noticed that despite the installation offered by its insulation blankets the electric motor driving the Beta Gimbal Assembly (BGA) that rotated the Port-6 SAW had experienced a strain and stalled. The motor was restarted and continued to run normally. Engineers at Houston continued to monitor both the Alpha and Beta drive motors.

The crew took a rest day on December 25, and January 1, 2002 to celebrate Christmas and New Year. Although they had to complete their daily exercise regime, they also took time to relax and to talk to their families and friends. On the subject of holidays, Bursch would write,

“The holidays were a nice break from the rapid pace of a Shuttle mission. I kept thinking about what several experienced Expedition crew members had told me; the Shuttle mission is a sprint, and the Station mission is a marathon. Of course, being away from family during the holidays is always tough. It was very hard for me to be away from my family, but I couldn’t help but think of all of the service men and women that were away from their families as well. And I also couldn’t help but think about the tens of thousands of people that were missing friends and family over the holidays because of the terrorist acts of September 11th. And for them there would be no future reunion. I suddenly felt very fortunate to have a healthy family on Earth, knowing that they were sharing the holidays with loved ones.’’

With the holiday period over, the crew returned to their experiments. Both the Active Rack Isolation System ISS Characterisation Experiment (ARIS-ICE) and the Experiment on Physics of Colloids in Space (EXPPCS) were halted on December 21, and resumed on January 2. The Payload Operation Centre (POC) in Huntsville sent commands to activate the experiments and monitored them as the crew went about their daily tasks. All three men completed their Crew Interaction Questionnaires on December 26-27.

Walz and Bursch both participated in the H-Reflex and the Pulmonary Function Facility (PuFF) experiments. The first experiment studied the spinal cord’s adaptation to microgravity. The second studied the effects of spaceflight on lung function. The same pair of astronauts had the opportunity to practise operating the SSRMS on January 3. In moving the SSRMS from one location to another on the exterior of ISS, Walz and Bursch allowed controllers in Houston to record the strains experienced when the arm separated from the fixture holding it to the station. Walz described the crew’s daily participation in the station’s numerous experiments in the following terms:

“We’re like a lab technician: we’ll be performing media exchanges for samples, we’ll be checking to ensure that the samples are growing as planned, we’ll report to the ground if there’re any anomalies, we have status checks to perform every day. So, it’s just, once we get things started, to make sure everything progresses per the timeline, and then at the end to make sure that we terminate the experiment properly so that when we bring the samples home, the scientists will be able to make the proper evaluations.”

On January 7, the EXPPCS began a 120-hour run, the longest yet. On the same date the ARIS-ICE science team began a series of one-minute isolation tests of their equipment using new control software. The crew also checked the individual radiation badges and the monitoring equipment connected with the Extravehicular Activity Radiation Monitoring experiment (EVARM). The radiation badges would be placed inside the cooling garments of pressure suits during future EVAs to monitor radiation reaching the wearer’s skin, eyes, and internal organs. Their first use would be on the STS-110 Shuttle flight when it visited ISS later in the year. Walz and Bursch completed the first session of the Renal Stone Experiment, a study of the risk of astronauts developing kidney stones during long-duration flights. Over one 24-hour period the two men monitored their diet and collected samples for return to Earth each time they urinated. They also had to keep logbooks throughout the period of the experiment.

Also on January 7, Bursch removed the hard drive from the Command & Control-2 (C&C-2) computer and replaced it with a new solid-state mass memory card, with three times the memory of the old drive. The computer was located in Avionics Rack-3 in Destiny, from where it processed all commands from Huntsville to the experiments and the flow of telemetry from the experiments back to Huntsville. The new memory card had been delivered to ISS on STS-108.

During the week the crew began preparations for their first EVA, which Walz described in his pre-flight interview published on the NASA Human Spaceflight website,

“Well, the spacewalk that Yuri and I will do is to move the first Strela cargo boom, which came up during the 2A.2a flight, and we’re going to move that from the PMA to the Docking Compartment. And so, we will use the Strela that comes up in the Docking Compartment to drive us over from the Docking Compartment to the PMA, sort of lash the second Strela on, and then bring it over. So it should be a very visually interesting EVA because I’ll be hanging at the end of the Strela … being transferred in free space, with this other large structure. So I think it’s going to be very exciting.’’

That EVA began at 15:59 January 14, when Onufrienko and Walz left Pirs wearing Russian Orlan pressure suits. They assembled and installed an extension to the Strela-1 crane mounted on the exterior of Pirs. Their main task was use the Strela-1 crane to position themselves so that they could detach and reposition the Strela-2 crane from PMA-1 to the base plate on the opposite side of the exterior of Pirs to the Strela-1 crane. Strela-2 was relocated at 19: 31. With the relocation complete the two cranes would be able to work in tandem during future EVAs and construction of ISS. The two men also deployed an amateur radio antenna on an EVA handrail at the end of Zarya. They returned to Pirs and prepressurised the airlock at 22: 02, after an EVA lasting 6 hours 3 minutes. Immediately after the EVA all three crewmen completed a turn on the PuFF experiment, to study the evenness of gas exchange in their lungs.

On the ground the Active Rack Isolation System (ARIS) control team in Huntsville down-linked data from their experiment and sent new software commands to their equipment in order to maintain good housekeeping on the data storage disk. The EXPPCS completed the 120-hour run begun on January 7. The experiment then began a new 24-hour run, on January 21. This was the last run before a new set of fractal gel tests that would last approximately five weeks and would prevent the crew from examining other samples held within the experiment. All three men completed their Crew Interactions Questionnaire and received new Crew Earth Observations targets, which they would photograph if the opportunity arose.

During the week following the EVA, Walz worked with controllers on the ground to remove the hard drive from the C&C-1 computer and replace it with a solid-state mass memory unit. The task took over four hours, but C&C-1 was brought on-line as the ISS back-up computer on January 23. Meanwhile, Onufrienko and Bursch replenished the two Orlan EVA suits worn on January 14, and prepared the equipment that they would install on the exterior of ISS during their second EVA. Of the 25 experiments planned for Expedition-4, 15 were in progress at this time. During his sleep period on January 24, Bursch was disturbed by a noise. Investigation revealed that one of the push-rods on the ARIS-ICE experiment was broken.

Onufrienko and Bursch began the Expedition’s second EVA at 09: 19, January 25, when they left Pirs dressed in Orlan pressure suits to mount deflectors behind six of Zvezda’s manoeuvring thrusters. They also recovered the Kroma-1-0 experiment package, which had been collecting samples of the thruster effluent deposited on the side of Zvezda when the thrusters fired. They then installed the fresh Kroma-1 collector package in its place. A second ham radio antenna was placed on the exterior of Zvezda along with the Plantan-M package, which was an experiment designed to detect neutral low-energy nuclei both from the Sun and from outside the Solar System. They also installed three materials exposure experiments on the exterior of Zvezda. Finally, they installed fairleads on Zvezda’s EVA handrails, guides to prevent an EVA astronaut’s safety tether from fouling equipment mounted on the exterior of the module. The EVA ended at 15: 18, after 5 hours 59 minutes. On January 26, Onufrienko and Bursch completed their post-EVA PuFF experiments.

January ended with a quiet week during which the crew changed the hard drive in the C&C-3 computer for a solid-state mass memory unit. The crew tested the station’s communication systems in an attempt to eradicate an echo that was degrading audio communications. The KURS rendezvous equipment was removed from Progress M1-7 for return to Earth, where it would be refurbished and reused. They also installed a laptop computer in the Quest airlock. On January 29, they withdrew the EVARM radiation badges from the pockets of their liquid-cooled EVA undergarments and recorded the dosages for transmission to the ground. Bursch also logged his dietary data as part of the Renal Stone Experiment. The broken push – rod on the ARIS-ICE experiment was removed and replaced on January 30.

At 08: 00, February 4, the Expedition-4 crew’s 60th day in space, the main computer in Zvezda crashed, disrupting the station’s attitude control. The crew began powering down back-up systems and all experiments in case of a decrease in electrical power caused by the station’s SAWs losing their lock on the sun. Controllers in Houston and Korolev worked together to restart the computer, which was achieved at 10: 30. One hour later the station’s attitude control system was back on line. Power was restored to sensitive experiments within 6 hours and everything was back to normal 24 hours after the computer crash. EXPRESS Rack 4, in Destiny, was the first to be powered on, as it held the Bio-technology Refrigerator and the PCG-STES which both contained biological samples. The MAMS had undergone a period of maintenance prior to the computer crash and was powered on the day after the crash. EXPRESS Racks 1 and 2, and the Space Acceleration Measurement System (SAMS) experiment were powered on during February 5, and the crew began preparations for a 72-hour run of the EXPPCS. EarthKAM was re-instated in Zvezda’s window, one week early. The experiment allowed Middle School children to command cameras on ISS to expose photographs of Earth’s surface. NASA subsequently published the photographs on the Internet. Additional schools, including one in Germany, had joined the experiment since it was shut down by the Expedition-3 crew in anticipation

|

Figure 14. Expedition-4: Yuri Onufrienko works with equipment in Zvezda. In the top right – hand corner of the view is an American-Russian dictionary. |

of the school holiday period. Fifty images had been downloaded since the cameras were reinstalled following the school holiday. Activities related to the Education Payload Operation-4 (EPO), which included the crew setting up and video taping a series of simple experiments, was rescheduled from February 4-5.

Onufrienko celebrated his 41st birthday on February 6. Two days later, the crew began to take an inventory of the equipment and food onboard to help planners work towards re-stocking ISS for the Expedition-5 crew. On February 13, they began a Human Research Facility (HRF) workstation test. The following day they carried out testing of the ultrasound life science equipment. The day after that they were familiarising themselves with the Zeolite Crystal Growth furnace before commencing that experiment programme. They also activated one of the cylinders in the PCG-STES Unit 7, which would be used to grow mustard seeds harvested on ISS by the Expedition-2 crew and the Advanced Culture (ADVASC) plant growth experiment.

On the same day a Remote Power Conversion Module (RPCM) failed. The RPCM distributed electricity to the station’s systems. The crew worked with engineers in Houston to repair the RPCM over the next few days. Bursch and Walz replaced a circuit breaker box using a spare held on ISS and thereby restored power to the non-essential equipment in Destiny. The repair required Bursch’s sleep station in the laboratory module to be removed. Before it was re-established they took the opportunity to install additional high-density radiation protection bricks behind it.

On February 15, the EXPPCS began a 120-hour run. A planned update of the station’s computer software, to prepare the computer system for the installation of the Starboard-0 (S-0) ITS during the flight of STS-110, in April 2002, was delayed until after the EVA planned for February 20.

That EVA began at 06:38, when Walz and Bursch made the first egress from Quest without a Shuttle docked to the station. Both men employed a new combination of pure oxygen and exercise to purge the nitrogen from their bloodstream. They wore American EMUs and for the first time the Intravehicular Officer, responsible for supporting the EVA astronauts, Joe Tanner, himself an astronaut, was based in the control room at Houston, rather than in orbit. Throughout the EVA Onufrienko used the video cameras on the SSRMS to view his colleagues’ activities. The Americans designated this Stage EVA, “US EVA-1’’. The two astronauts removed two power cables from their stowage area on the exterior of Destiny and plugged them in to a cable near the base of the Z-1 Truss. Plans to disconnect the cables and return them to storage at the end of the test were cancelled when plugging them in caused unpredicted power readings in the current conversion unit in the circuit that they completed. Working separately, Walz removed four thermal blankets from the Z-1 Truss and stowed them within the truss, while Bursch retrieved tools that would be used during the four EVAs planned during STS-110 and carried them to the Quest airlock. They then joined together to secure the locks holding oxygen tanks to the exterior of Quest that were looser than required following their original installation. They removed two adapters that had been used to hold the Russian Strela cranes on the exterior of the station. One was relocated to the exterior of Zarya, while the other was placed inside the Quest airlock. Finally, they inspected external cable connectors and the Materials on International Space Station Experiment (MISSE), where they found that some of the exposure samples had peeled back from their mounts. Walz and Bursch returned to Quest at the end of their planned activities. The hatch was closed and the EVA ended at 12: 25, after 5 hours 47 minutes. Throughout the EVA the MAMS and SAMS equipment recorded the vibrations associated with the external activities. Both EVA astronauts participated in PuFF and EVARM experiments prior to, during, and following their activities.

They were two hours late going to bed at the end of the day. The delay was caused when an unpleasant odour began emanating from the equipment used to clean the air scrubbers in the EMUs that they had used during their EVA. On instruction from Houston the equipment was powered off and the Quest airlock internal hatch was closed to prevent the odour prevailing further into the station. Some of the station’s ventilation fans were powered off, while the system used to scrub the station’s air was powered on in Destiny. All three men slept in Zvezda that night. On February 21, controllers at Korolev used the rocket motors in the Progress M1-7 spacecraft docked to ISS to raise the station’s orbit.

The crew completed their first activities as part of the Education Payload 4 experiment on February 25. During the activities they used a series of small toys to demonstrate basic principles of physics and the microgravity environment. Three days later they activated Cylinder 8 of the PCG-STES experiment. In Destiny, EXPRESS Racks 1, 2, and 4 continued to function normally.

At the beginning of March, STS-109 was launched on a solo flight to repair the Hubble Space Telescope. On ISS the crew spent the first week of the month repairing a shock absorber in the ARIS-ICE and then bringing the experiment back on-line. They also recovered air and water samples from the ADVASC experiment. The samples would be stored before being returned to Earth for study.

Earthkam’s cameras were once again made available to schoolchildren. To prepare the Earthkam experiment the astronauts needed to move the SSRMS, which was partially blocking the window in Destiny through which the cameras exposed their images. The primary avionics system failed to release the brakes on the SSRMS, requiring the crew to use the secondary avionics system in order to complete the move. An investigation into the failure began immediately on the ground in Houston. On March 7 the crew began a training run, putting the SSRMS through the series of manoeuvres that it would be required to perform when STS-110 delivered the S-0 Truss in April. During the same day, software tests were sent up to the primary and secondary computer workstations used to control the SSRMS, but the secondary station failed to boot up. When that happened the SSRMS was left parked in a safe position while another investigation began, to identify why the boot-up had failed. During the following week the SSRMS was used to carry out a video review of the station’s radiators and SAWs. The secondary software was used to drive the arm. Also at that time, the crew completed an inventory of items on ISS, stowing equipment and preparing items for return to Earth in advance of STS-110’s visit, when there would be a total of ten people living and working on the station. On March 19, the rubbish-filled Progress M1-7 was sealed and manoeuvred away from Zvezda’s wake, at 12:43. It re-entered the atmosphere and burned up a few hours later, after releasing the short-lived Kolibiri-2000 sub-satellite into orbit.