A CAPITOL PRESS CONFERENCE

In 1986, Shepard reflected back on that auspicious day. “After the ceremony in the Rose Garden, the president invited the astronauts into the Oval Office to talk about the future of the space program. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson had great political instincts. They knew the country needed a lift, and they saw space flight as a rallying point. We talked at great length about it. The president said he knew I had a parade up Pennsylvania Avenue, but first he wanted me to go with him to a meeting of the National Association of Broadcasters. He just grabbed me, and we got in his car and drove to the meeting. ‘I want you to say a few words to these guys,’ Kennedy said. I forget what I said; it was something like it was nice to be back. Everybody jumped to their feet and cheered. I couldn’t believe the reception there.” [15]

According to the 1994 book, Moon Shot, based on interviews with the astronaut, “Shepard did not like what was happening. His patience was evaporating swiftly. He disliked, intensely, being used. Walking in on the broadcasters’ convention with the president would be showing off a war trophy named Shepard, and it smelled. He mollified himself somewhat by remembering that no matter who he was, Kennedy was also his commander in chief, and you can excuse almost anything if you’re obeying orders. The fact that he and Louise received a standing ovation did diminish his objections to some degree.” [16]

|

Vice President Lyndon Johnson sits between the Shepards as the motorcade prepares to leave the White House. (Photo: Associated Press) |

Further cheers went up as Alan and Louise Shepard, with Vice President Johnson between them, climbed into a limousine which then left the White House for a slow ride along the traditional parade route of American heroes, from the White House out onto Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues to the Capitol, where he was to receive a reception by Congress.

A massive, cheering crowd estimated at around a quarter of a million people lined the sidewalks. There were no military bands playing, no troops, and no spectacular displays of the nation’s might. Government officials had earlier decided that it would be inappropriate to give their official blessing to a star-spangled military parade and organized welcome, so the citizens of Washington took matters into their own hands and by their tumultuous welcome gave the nation’s first spacemen and his fellows in the following limousines a cacophony of unrehearsed affection that made the day’s proceedings all the more memorable.

“I’ll never forget riding to the Capitol in an open convertible with Johnson and Louise,” Shepard later pointed out. “Johnson kept saying, ‘Look at all these people… Shepard, you and Louise get up on top of this thing.’ So we sat up on the back. When we got to the Capitol, Johnson said, ‘Well, Shepard, now that you’re a famous man, let me give you some advice. Never pass up an opportunity for a free lunch or a chance to go to the men’s room.’” [17]

|

The Shepards wave to crowds lining the motorcade route along Washington’s 15th Street. (Photo: Associated Press) |

|

On arrival at the east portico of the Capitol, Shepard alighted along with the other astronauts in front of a massive crowd. All seven would have been stunned by the thousands of excited people who had gathered in the plaza hoping to catch a glimpse of them but held back by police lines and ropes. Led by Vice President Johnson, the party ascended the broad steps of the Capitol to meet House Speaker Sam Rayburn, House Majority Leader John McCormack, and other dignitaries. Shepard expressed his sincere appreciation for the warm welcome by the lawmakers, and indicated he would have far more to say at his later press conference. He seemed quite composed in front of the noisy, jostling crowd, speaking seldom, smiling often, and watching the scene before him with amazement.

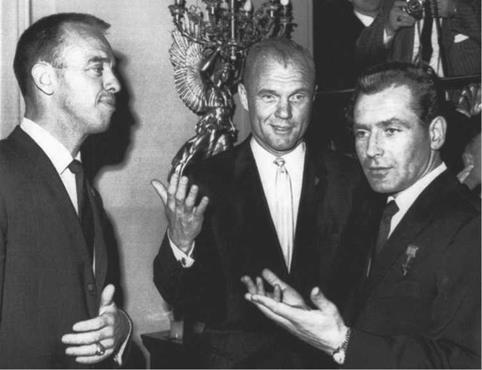

After waving at the crowds and saying a few words, Shepard moved on to the more formal part of the occasion, which was held in the old Supreme Court chamber, just a few steps down from the Senate. Then it was off to the State Department for his press conference, chaired and introduced by NASA Administrator James Webb. As Shepard entered the auditorium, 500 news reporters rose and gave him a standing ovation, something reporters seldom do. With his six fellow astronauts flanking him on his right and James Webb, Robert Gilruth and other NASA officials on his left he gave an account of the flight “we made” the previous Friday. He acknowledged the acclaim, but refused to accept it all for himself.

|

As Vice President Johnson looks on, Shepard prepares to give a news conference at the Capitol Building. (Photo: Associated Press) |

To the President, to the Congress, and to the reporters, Shepard stressed over and over that it was not “he” but “we” who did the thing that they were praising him for. “I am acutely aware,” he said, “of the hundreds of individuals who made this flight possible.” But as Robert Gilruth, director of the Mercury program pointed out at the conference, it was Alan Shepard “who really broke the ice for all of us” and showed America the way into the great new frontier of space [18].

That night, after the glare of the public spotlight, Shepard and his wife and family spent a quiet evening together in the seclusion of Langley Air Force Base, Virginia, talking over recent events.

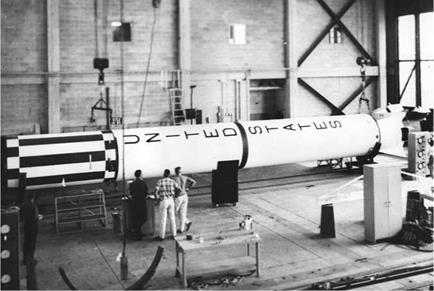

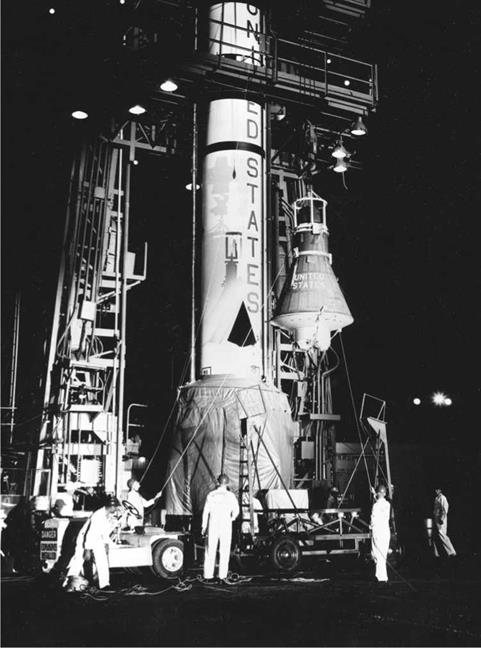

Even as the nation celebrated the successful first American space flight by Alan Shepard, most of the attention at NASA had turned to the future and was focused on the second Mercury flight and those which would follow it. Soon 40-year-old Virgil Grissom, better known as Gus, would step up to the plate to deliver the all-important second suborbital test in the spacecraft he had patriotically named Liberty Bell 7.

|

The NASA medal presented to Shepard earlier that day is proudly worn at the news conference. (Photo: Associated Press) |

|

Next to fly: Mercury astronaut Virgil (‘Gus’) Grissom. (Photo: NASA) |