Epilogue

From the outset, the Freedom 7 spacecraft was never intended to serve any practical purpose after its history-making flight, let alone fly into space again. Instead, it was gifted to the American people by NASA, to be preserved in a museum environment and openly exhibited for everyone to visit.

Sadly, the Soviet Union was not quite as kind to its flown manned spacecraft. In one instance the Vostok 2 capsule, flown by Gherman Titov in making history’s first day-long space flight, was converted and used as a training vessel for the upcoming Voskhod human space flight program. During a failed test for a new soft-landing parachute system, the capsule struck the ground so hard that it was crushed beyond repair. There would appear to be no indication of what happened to the remains, but there are lingering fears that it may have been unceremoniously scrapped.

Unlike his pioneering spacecraft, Alan Shepard would eventually fly into space a second time. In 1971 he commanded the Apollo 14 mission, fulfilling his long-held dream of walking on the surface of the Moon.

More than five decades on, the smaller spacecraft and the man who flew in it have both entered the history books for what they accomplished on 5 May 1961.

THE SPACECRAFT

Following its return by helicopter to Cape Canaveral, the Freedom 7 spacecraft was subjected to several days of minute examination by engineers and technicians. It was then released for a pre-scheduled tour abroad, ahead of being placed on permanent display in the United States. On 25 May, just three weeks after it had been recovered from the Atlantic, Freedom 7 went on display at the 24th International Aeronautical Show in Paris, France. By the end of the show on 4 June, some 650,000 fascinated attendees had taken the opportunity to view the spacecraft up close.

C. Burgess, Freedom 7: The Historic Flight of Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Springer Praxis Books, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-01156-1_8, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014

|

From Paris Freedom 7 was shipped to Italy, where it was on display from 13-25 June at the Rassegna International Electronic and Nuclear Fair in Rome. Amazingly, it drew more visitors than in Paris, with around 750,000 people lining up to inspect it. The spacecraft was then returned to the United States to undergo intensive study at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. After that it was returned to its maker, the McDonnell Aircraft Company in St. Louis, Missouri, to be taken apart, inspected, reconstructed, and prepared for public exhibition in the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C.

Four months later, on 23 October 1961, Freedom 7 was officially presented to the Smithsonian by NASA Administrator James Webb. In his presentation speech, Webb declared, “To Americans seeking answers, proof that man can survive in the hostile realms of space is not enough. A solid and meaningful foundation for public support and the basis for our Apollo man-in-space effort is that U. S. astronauts are going into space to do useful work in the cause of all their fellow men.” [1] Freedom 7 was placed on public display in the Quonset Hut – or Air Museum Building – in the South Yard Restrictions of the National Air and Space Museum.

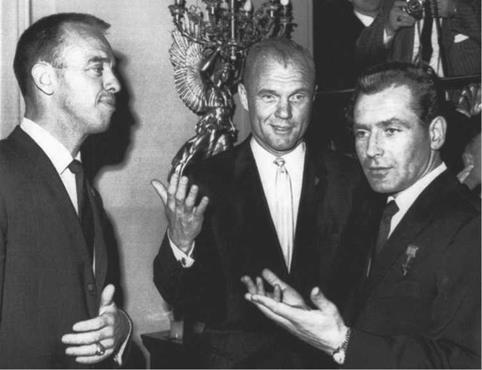

East met West in May 1962 when Vostok 2 cosmonaut Gherman Titov paid an official visit to the United States. Accompanied by Mercury astronaut John Glenn, who had by then accomplished America’s first manned orbital flight, and a veritable cavalcade of official vehicles and press photographers, Titov was shown some of the sights around the nation’s capital, one highlight being a brief visit to the National Air and Space Museum where the cosmonaut inspected the Freedom 7 spacecraft.

In 1965, due to keen interest abroad and through the courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution, the Freedom 7 spacecraft was temporarily loaned to the Science Museum in Kensington, London, for a five-month exhibition. It was shipped from New York to London on the Cunard-Anchor liner Sidonia and delivered amid great fanfare on 17 September. The exhibition (which was advertised as lasting from 5 October 1965 to 28 February 1966) proved to be extremely popular. By the end of February it had been visited by 110,000 people. Among the visitors were Her Majesty the Queen and H. R.H. the Duke of Edinburgh, who viewed Freedom 7 on 10 November [2].

Within the spacecraft was a lifelike model of Alan Shepard lying on his back as if preparing for liftoff, his left hand grasping the abort handle ready to fire the escape tower in the event of a mishap.

Due to great public interest, the Smithsonian agreed to an extension of the loan, allowing the exhibition to remain open until 1 May 1966. Eventually, the spacecraft was viewed by 356,000 visitors. On 18 May it was transferred to the Royal Scottish Museum in Edinburgh, where it was exhibited for several weeks in conjunction with a public talk by John Glenn on 3 June. After the exhibit was closed on 11 September, the spacecraft remained in the museum out of public view for a further three weeks to accommodate a visiting Smithsonian dignitary. Overall, the Edinburgh exhibition was seen by in excess of 200,000 visitors, this number having been collected by the “electric eye” of the museum [3].

Following its overseas sojourn, Freedom 7 was returned to the United States and placed back on public display at the Smithsonian, where it would remain for the next 32 years.

In December 1998 the spacecraft was out on lengthy loan once again, this time to the U. S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The exhibition had been mounted

|

|

America’s first manned spacecraft held a great fascination for young and old alike. (Photo: Smithsonian Institution) |

to honor the memory of pilot Alan Shepard, who died earlier that year. Shepard had graduated from the Academy in 1945. Freedom 7 would remain on public display at the Armel-Leftwich Visitor Center for 14 years, honored with a place in the rotunda leading to the exhibit area. During this time, it was encased in acrylic Plexiglas and had its periscope deployed.

On 18 January 2012 the Naval Academy announced that Freedom 7 would soon be moved from Maryland to Massachusetts and placed on temporary exhibition until December 2015 in a space gallery at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Columbus Point, Boston. The spacecraft’s public debut on 12 September 2012 was to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the “We choose to go to the Moon” speech that Kennedy famously delivered at Rice University in Houston in 1962.

Prior to the spacecraft taking up temporary residence in Boston, there was a major problem to resolve. This fell to experts at the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Center in Hutchinson, Kansas, which, in consultation with the Smithsonian, developed and

|

Alan Shepard and John Glenn with cosmonaut Gherman Titov at the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D. C. (Photo: United Press International) |

built a special cradle for exhibiting Freedom 7 in Boston. The cradle was constructed using steel that had been washed and sandblasted in order to remove any corrosion. It was then covered with a clear protectant and painted with rubber padding where it would support the spacecraft. Jim Remar, president and chief operating officer at the Cosmosphere, said the discarded acrylic cover had been a less than ideal means of preserving the historic artifact. “The acrylic prevented the spacecraft from breathing. As materials deteriorate, they emit gas. The acrylic trapped the off-gassing in the spacecraft and [this] could accelerate or increase the rate of deterioration. With the removal of the acrylic, it is now able to breathe and the off-gas is exhausted out.” [4] However, Freedom 7’sjourney will not end there. In 2016 the Smithsonian plans to display it as part of a major, brand new Apollo-themed gallery that tells through displays the monumental story of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs.