MR-1 LAUNCH FAILURE

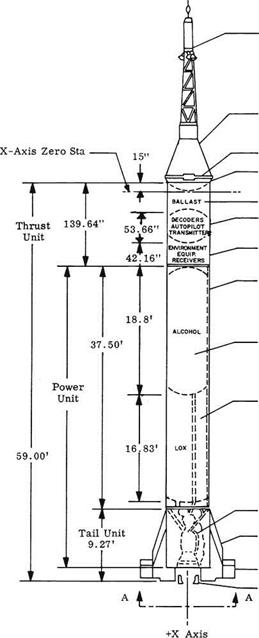

Mercury-Redstone 1 (MR-1) was to be the first qualifying flight of an unmanned Mercury capsule mated with a Redstone rocket. The launch, set to take place from Pad 5 of Cape Canaveral’s Air Force Launch Complex 56, was to be a full test of the spacecraft’s automated flight controls, as well as the launch, tracking and recovery operations on the ground. It was also intended to provide a test of the Mercury – Redstone’s automatic in-flight abort sensing system, which would be operating in an “open loop” mode. Basically, this meant that because it was an unmanned test of the system and there were no real safety issues, an abort signal would simply be ignored in order to prevent a false signal from terminating the flight needlessly.

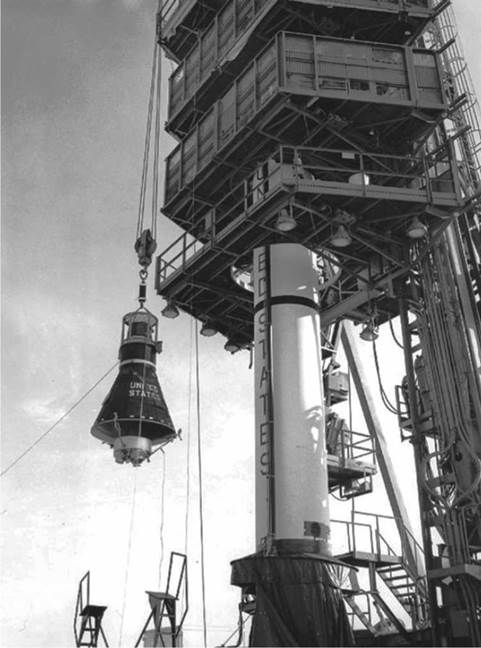

On 22 July 1960, after the capsule systems tests in St. Louis, Missouri, Mercury Capsule No. 2 was shipped to Huntsville, where the one-ton capsule was mated with its Redstone. Both then underwent a series of checks to ensure their compatibility. Next, the total assembly, now some 83 feet long, was shipped to Cape Canaveral, arriving on 24 July. The escape tower was then prepared, and hangar activities such as the installation of parachutes and pyrotechnics were completed in time to transport the spacecraft to the launch pad on 26 September, where the rocket, enclosed by the service structure gantry, was waiting.

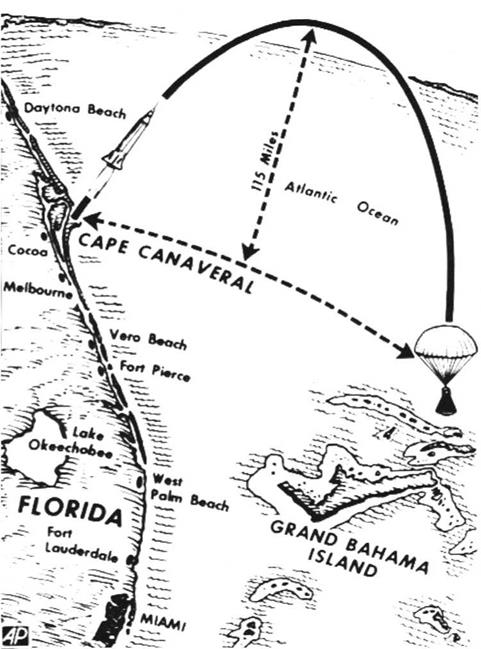

The first launch attempt was set for 7 November, with the intent of hurling the capsule about 220 miles over the Atlantic into a target area northwest of Grand Bahama Island. Things went smoothly until a problem caused the test to be canceled 22 minutes prior to the planned time of liftoff. According to ‘Luge’ Luetjen from the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, who was then serving as the company’s Redstone Mission Capsule Controller, “It was noted that the helium pressure in the spacecraft control systems had dropped below the acceptable level. A leak in the system, unfortunately under the heat shield, was obvious, and as a result the launch was scrubbed. The spacecraft was removed from the booster and the heat shield dropped to expose the culprit, a leaky relief valve. It, and a toroidal hydrogen peroxide tank were replaced, plus a minor wiring change was made as the result of an earlier test at Wallops Island, Virginia. The spacecraft was reassembled, remated to the booster, and appropriate tests rerun in order to confirm the spacecraft’s integrity and that the problem had indeed been fixed.” [5]

A second launch attempt was scheduled for 21 November. Two days after the 7 November launch scrub, Senator John F. Kennedy narrowly beat Richard M. Nixon, the incumbent vice president, in the election to become the 35th President of the United States. It would prove a momentous victory in terms of space flight history.

On hand to observe the second attempt to launch MR-1 – as indeed for the first – were the seven Mercury astronauts. That morning there was only a minor one-hour delay to enable technicians to fix a leak in the capsule’s hydrogen peroxide system, which slipped the time of liftoff to 9.00 a. m. (EST). There were no further delays. Right on the hour the firing command was issued from the Mercury Control Center. The booster ignited, then one second later the Rocketdyne A-7 engine unexpectedly shut down. During that interval, the booster had actually lifted a little less than four inches off its pedestal. After the engine cut off, the vehicle settled back down onto its

|

|

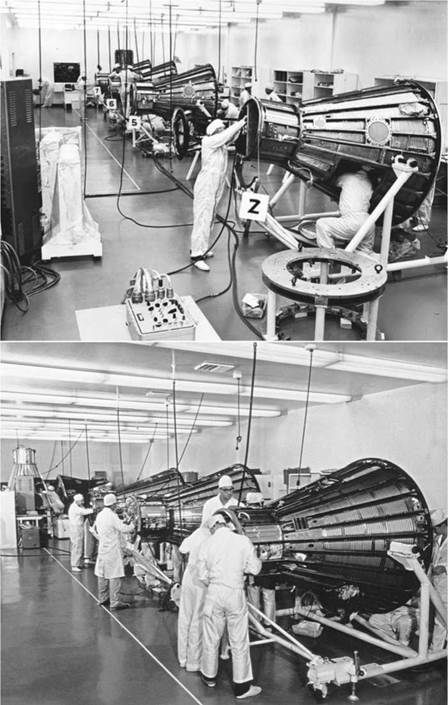

The “clean room” at the McDonnell Aircraft plant in St. Louis, Missouri, where the Mercury capsules took shape. Extreme precautions were taken to prevent dust and metal particles infiltrating sensitive areas. In the upper photo, Spacecraft No. 2 is to the fore; it would be utilized on two Mercury-Redstone flights. (Photo: McDonnell Aircraft Corporation).

|

•r

•r

""

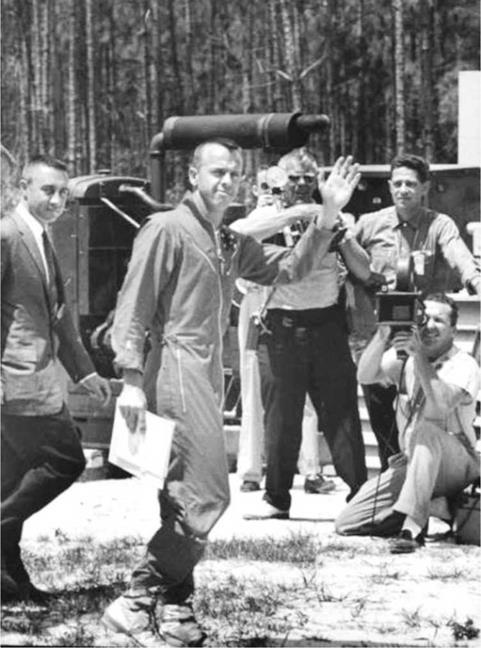

On 21 November 1960 preparations continue for launching the MR-1 mission from Cape Canaveral. (Photo: NASA)

fins, slightly deforming their frames. Incredulous controllers in the blockhouse could only watch as the Redstone wobbled after the set-down impact, still venting liquid oxygen. Fortunately the 66,000-pound assembly managed to remain upright and did not explode.

Compounding the problem, the engine cutoff had initiated the emergency escape system, which activated the escape tower and recovery sequence. The escape tower’s engine suddenly ignited, releasing it from the Mercury capsule and sending it soaring over 4,000 feet into the air. Eventually, it crashed down on a beach 400 yards from the pad. As stated by NASA in This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury, three seconds after the escape rocket separated, “the drogue parachute shot upward, and then the main chute spurted out of the top of the capsule, followed by the reserve, and both fluttered down alongside the Redstone.” [6] The radio antenna fairing was also ejected in the process.

Clearly, the only thing that would launch that day was the escape tower. One can only imagine the feelings of the astronauts as they witnessed the entire mishap.

Securing the slightly wrinkled booster and the still firmly attached capsule had to be carried out with the utmost caution, as the booster’s destruct system could not be disarmed until the battery that powered it had fully depleted, which was not until the next morning. Also, the spacecraft was still on internal power and its pyrotechnics – including the posigrade and retrograde rockets – were still armed. Furthermore, it was not possible to open the vent valves and undertake the defueling process. It was therefore necessary to wait until the Redstone’s liquid oxygen had fully evaporated, which would take 24 hours. The other worrying safety issue was the main parachute, which was dangling from the top of the capsule. Any strong gust of wind could cause the canopy to billow and topple the vehicle off its pedestal. Fortunately, the weather remained calm.

The following day, Walter F. Burke of McDonnell volunteered to lead a squad of men to disarm the pyrotechnics and other immediate problems [7]. The liquid oxygen tank was vented, as were the high-pressure nitrogen spheres in the pneumatic system of the engine. The fuel and hydrogen peroxide tanks were then emptied. All circuits were deactivated, the service structure was rolled back in, and finally the booster and capsule disarming was finished. The next afternoon NASA’s Chief of Manned Space Flight, George M. Low, said that the MR-1 failure was believed to have been caused by the premature disconnection of a booster tail plug.

According to The Mercury-Redstone Project issued by the Marshall Space Flight Center in September 1961:

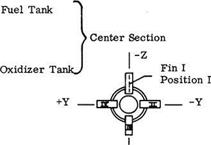

The investigation which followed found the cause of the engine shutdown to be due to a “sneak” circuit created when the two electrical connectors in Fin II disconnected in the reverse order. Normally the 60-pin control connector separates before the 4-pin power connector. However, during vehicle erection and alignment on the launch pedestal, a tactical Redstone control cable was substituted for the specially shortened Mercury cable. The cable clamping block was then adjusted, but apparently not enough to fully compensate for the longer Redstone cable.

|

|

The escape tower plowed into beach sand some 400 yards from the pad. (Photo: NASA) |

Because of the improper mechanical adjustments, the power plug disconnected 29 milliseconds prior to the control plug. This permitted part of a three-amp current, which would have normally returned to ground through the power plug, to pass through the “normal cutoff’ relay and its ground diode. The cutoff terminated thrust and jettisoned the escape tower [8].

Project Mercury Director Robert R. Gilruth added that a faulty electrical circuit between the ground apparatus and the booster had simulated a normal booster cutoff signal. Ordinarily, this would be given in flight, after the booster had been taken to its designed speed and altitude of about 40 miles. The normal sequence was then for the escape-rocket tower to separate; the recovery devices such as parachutes to be armed ready for deployment; and, when the booster’s thrust tailed off, the booster/capsule securing ring to be released. The separation of the escape tower took place normally, but the sea level atmospheric pressure led to the deployment of the drogue and main parachutes, and the weight of the capsule on the booster prevented its separation [9].

The late Guenter Wendt was a German-American engineer who had emigrated to the United States in 1949. He found ready employment with the McDonnell Aircraft

Corporation, and later became well known for his work in America’s space program. As the man in charge of the spacecraft close-out crew on the pad, he soon gained the respect of the astronauts. To the company his title was Pad Leader, but the astronauts jokingly (and affectionately) enjoyed referring to him as their “Pad Fuhrer,” and he fell in with their humor. Wendt had been at the Cape for the failed MR-1 launch, and described the follow-on events as he saw them during a 2001 interview with Francis French.

“When we started off, we had one Redstone that lifted off about four inches and set back down. It had a little kink in it, and we could not depressurize the tank – the tank was building up pressure. I go back to the blockhouse, and the next thing I hear are [Kurt] Debus and John Yardley discussing it. Debus tells the pad safety officer to call the base and get some guns, [because] he is going to shoot holes in the oxygen tank to relieve the pressure! John Yardley says, ‘Like hell you do! I have a perfect, safe spacecraft out there, it’s the only one I have right now. If you shoot holes, the thing is going to blow up and I’ll have no spacecraft!’

“So, what do we do? We get our engineers together to see what we could do to disarm the rocket. The first thing is, we have to get rid of the pressure in the oxygen tank. How can we do that? One of the ways is to send a mechanic out there, into the tail end of the rocket, to hook up a quarter-inch nitrogen line, then open up a hand valve. However, we don’t know what will happen, so when we open it, we run like hell back to the blockhouse! A guy by the name of Sonny came, he went out, opened it, ran like hell, and just about hit the blockhouse when a big stream of gas, tens of feet long, came out. But nothing blew up.

“Next, Yardley called me and said, ‘We’ve determined that, due to the sequencing – the main chute came out, the tower had left – the sequencer is looking at a half-G switch. When that thing activates, it will fire the retrorockets into the oxygen tank!’ So now, we are looking for someone to go out there and deactivate the circuitry. However, since the periscope had retracted, you have to drill out a bunch of rivets and open the periscope door, because the electrical umbilical plug is under it. Then four jumper wires have to be plugged in. So we were looking for people with no dependents to volunteer. If the retrorocket had fired, that would be it.

“After a long discussion, some of us volunteered to go out and do it. Before we did, we had Pad Safety set up a movie camera next to the blockhouse. If it blew, at least we’d know where the pieces went! We went up there. On the Mercury capsule, the hatch was bolted down with screws – you could move the washer, but the screws had to be tight. They had to be just matched. They needed to expand on the outside, because of the heat. I had a guy who had meticulously matched each screw to a perfect hole, and stored them on foam. We got up there, got the screws out and pitched them behind us. I will never forget that. We thought, he will kill us when he finds out what happened to his matched screws! We got the hatch open, found the two switches: click, click, and we were safe. We saved the spacecraft, though we needed a new booster.

“The people who made the decisions were right there, and they made the decisions. That’s what we got paid for!” [10]

|

McDonnell Aircraft Corporation’s Pad Leader, Guenter Wendt. (Photo: NASA) |

Ballast Section

Ballast Section

– f

– f