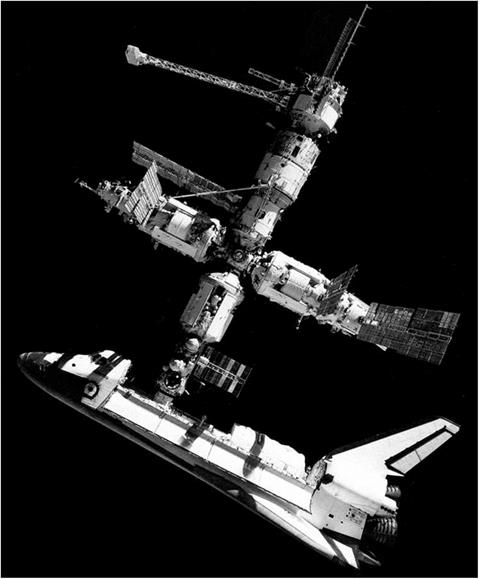

Freedom: The U. S. strikes back

NASA had desired a space station since the demise of Skylab in 1979, but the financial and technical constraints of the space shuttle program had made such an undertaking impossible. As we have already seen, the Soviet Union had made great strides in space technology and usability, and were far ahead of the Americans in this area of manned spaceflight. NASA was eager to use the space shuttle to gain back some of the ground that had been lost.

Many attempts had been made by the then NASA Administrator James Beggs to persuade the President and Congress to fund development of a new space station but he had always been unsuccessful. Despite this fact, in 1982 NASA went ahead and obtained eight different designs from the big aerospace contractors of the time, hoping that one of them would finally convince Congress of the value of a new station. Most of the contractors, however, came up with designs geared toward servicing and launching spacecraft rather than purely scientific research stations.

Finally, in January 1984, despite great opposition from some of his advisors, President Ronald Reagan announced the new space station in his State of the Union address, and directed NASA to assemble it within a decade. International partners such as Canada, Japan, and the European Space Agency (ESA) would provide hardware for the station, as well as technical support. NASA was to keep the first two years as a low-key definitions program in order not to incite the many scientists and military leaders who were against the project.

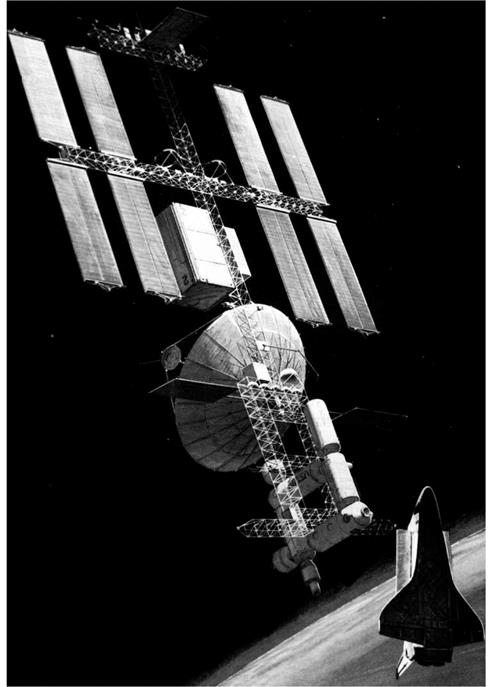

NASA had narrowed down the design options to four by March 1984, and the main baseline configuration chosen was the “Power Tower” design which had been submitted by Boeing/Grumman. The main reason for this choice was that it allowed the most flexibility for future expansion without adversely changing the stations overall mass; it kept NASA’s options open. The Power Tower provided a clear area for shuttle dockings, as well as predefined attachments for specific temporary payloads. It was thought that the entire assembly could be carried out by 12 shuttle launches over a З-year period, but other contractors doubted this. In late 1985 NASA

"We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful, economic and scientific gain. Tonight, / am directing NASA to develop a permanently manned space station and to do it within a decade."

President Ronald Rengnn State of the Union Message January 25. 1984

President Ronald Rengnn State of the Union Message January 25. 1984

Reagan gives state of the union message

|

|

|

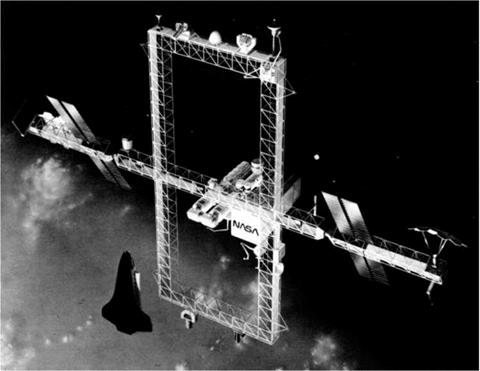

Rockwell “Dual Keel” design 1985 |

changed its baseline configuration, and abandoned the “Power Tower” concept that it had already spent a considerable amount of money on due to complaints from potential crews and engineers who felt that the design would not prove stable enough for scientific experiments. The “Dual Keel” design became the new baseline. It was based on Lockheed and McDonnell-Douglas designs, and was chosen because it was felt that it would provide a much stiffer structure, and therefore a better microgravity environment for experimentation. The crew complement was increased to eight to allow more scientific work to be carried out.

In 1988, space station Freedom, as it was now officially known, was going to cost at least $14.5 billion and would require 10 or 11 shuttle launches to complete. And it was felt by many that NASA was playing down the true cost by not including all shuttle launch costs. In addition, there were doubts that the space shuttle could reliably service such a station. The space shuttle was, of course, central to the plans to construct the space station. Its unique capability to carry large payloads into orbit and have a crew on board capable of joining the pieces together meant that literally nothing else could do the job. The United States was seriously lacking an unmanned heavy lift launch vehicle; the shuttle had been imposed on all commercial and military customers as the only game in town. Consequently, the space station and all other launch customers were left in disarray by the disaster that befell the space shuttle Challenger on 28 January 1986. The fact that the accident had largely been caused by NASA’s own mismanagement, as well as a flawed booster design, eroded confidence in NASA in other areas, and that included designing, building, launching, assembling, and maintaining a manned space station.

By far the biggest problem, however, was that NASA was trying to please everybody with the space station design. It was trying to offer a garage for assembly of interplanetary spacecraft, a massive variety of scientific laboratory facilities, including animal research, variable gravity, materials processing, life sciences and the like. The power requirements for all of these capabilities were massive, and would need solar arrays of the greatest quality. One station simply could not carry out all of these contradictory requirements; not without being a massively expensive leviathan, which is what it had become. The program was far too large for its own good, and NASA seemed more concerned with pushing the frontiers of technology instead of designing a station that they could actually launch and maintain within a reasonable budget. NASA needed to decide on the station’s primary use. Contradictions were caused because, for instance, animal research or spacecraft assembly would adversely affect the microgravity environment needed for materials processing or other scientific experiments.

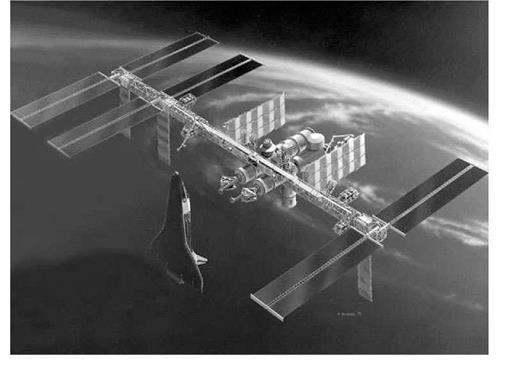

The situation was not improved by the Department of Defense, which in 1987 demanded full access to the station to carry out military research. NASA’s partners were incensed, and the situation had to be quickly resolved to ensure continued involvement. By 1989 the estimated cost had grown again, to $19 billion; and this was after NASA had deleted some capabilities from the station and reduced its power requirements. In addition, a new program to improve the performance of the space shuttles solid rocket motors was required to launch the ever-increasing weight of the station, which increased the overall cost even further. This trend was to continue until 1990, when Congress demanded a major rethink. The existing design, as well as being overweight and a long way over budget, was also going to require far more maintenance once it was built than NASA had planned for. It was estimated that around 3,000 hours of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) work would need to be carried out per year in contrast to NASA’s target of around 500 hours. The redesigned station, now nicknamed “Fred” by critics (to indicate that it was a cut down Freedom), was unveiled in March 1991, would cost around $16.9 billion and would take 23 shuttle launches to complete.

By the time the Freedom project was canceled in 1991, NASA had redesigned the station at least six times and spent over $11 billion without building a single piece of flight capable hardware. Valery Ryumin of Energia was heard to comment, “They’ve spent 10 years and $11 billion; if only we’d had a bit of that money. $11 billion and they haven’t done a thing; everything they’ve done in that decade was useless, none of it worked. Ten years and all they built was a wooden model.’’

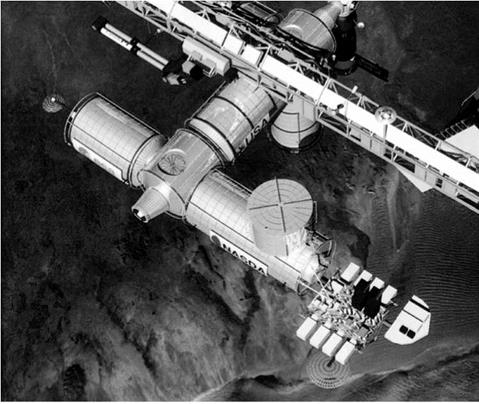

Although canceled in May 1991, the space station plan was quickly revived only one month later; but with a dramatically cut budget. It was not until 1993 that President Bill Clinton really tackled the problem directly. He demanded three new station designs, options A, B, and C, costing $5 billion, $7 billion, and $9 billion

|

Space station Fred—March 1991 |

respectively. Option A, which was based on a 1991 Freedom design, was chosen as the best compromise, and would cost $6 billion, but this would be without a habitation module that would be added later at additional cost. Nevertheless, the station’s critics in Congress remained skeptical, and a move to kill the entire project failed by a single vote. At this point, NASA introduced a new partner—Russia. Using Russian modules and technology would make the assembly of the station more efficient. Clinton saw an opportunity to tie the Russians into a program that would keep its engineers busy, and therefore less likely to get involved with other countries more questionable activities. It was only when this agreement was reached (Chapter 11) that things began to move forward; mostly because the station now had an acceptable political face.

In reality, the same problems that had plagued Freedom would continue into the ISS. It was never very clear what Freedom or the ISS was actually for. What goals did it set? The Soviets had always had the goal during the many iterations of Salyut to make each station more independent, more self-sustaining, than its predecessor. This kind of technology and operational capability would be necessary for the longer, far – reaching space flights of the future, like a manned mission to Mars. With Mir, Russia had almost achieved the ultimate goal of a “closed loop’’ spacecraft. However, Freedom and later the ISS would not have the same goal; there was nothing “closed

|

First ISS design—1993 |

loop” about the design, and this did not appear to be the goal in the future. When Ronald Reagan made his speech in 1984, he said, “America has always been greatest when we dared to be great. We can reach for greatness again. We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful, economic, and scientific gain.” This was not really the clear goal that NASA was looking for or needed, and it was not long before the old engineering maxim, “the better is the enemy of the good”, showed itself to be true.

The space station became far too big and complicated; NASA had designed a Rolls Royce when it only really needed a Mini.

|

|