SPACELAB

Having deciding to concentrate on the space shuttle program after the three visits to Skylab NASA lacked a space station of its own. However, in collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA), NASA developed the Spacelab. This made available a pick and mix of a pressurized module and open pallets that sat in the shuttle payload bay to allow scientific experiments for the duration of a shuttle mission. It was obviously nowhere near as good as the long-duration experiments that could be carried out aboard the Salyut stations, but it was the closest thing possible with the space shuttle. Critics pointed out that it was impossible to make the shuttle a completely gravity-free environment, as the movements of the relatively large crew, plus thrusters firings, would interfere with the results of many experiments. The project began in 1973 when NASA and ESA signed an agreement that outlined the components and responsibilities of the Spacelab project. The first engineering model of a pallet arrived at NASA in 1980, and went on to be used on the shuttle’s second flight in 1981. Most Spacelab missions could only last up to 10 days, but NASA added the Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) pallet to the shuttle and in 1992 STS-50, a Space – lab mission on Columbia, flew a 13-day mission. The longest shuttle mission, STS-80

|

STS-9 crew |

lasted for almost 18 days, and this represented the limit of the shuttle’s duration. In total twenty-four Spacelab missions would be flown on the shuttle, seventeen of them with the pressurized lab module, the first of which, STS-9, was launched on 28 November 1983 and lasted for 10 days.

Whilst not strictly speaking a space station component, Spacelab did shape the way NASA planned and undertook its science based missions. The crew’s schedule for these missions was extremely tight, with not a minute wasted; of course on a short mission with around the clock shifts of crew members it is acceptable and sensible to plan this way, but it would do nothing to help NASA plan for future space station operations, when it simply would not be possible to plan every last minute of the day.

The Soviets made maximum use of their new ferry craft capabilities on the 8 February 1984 with the launch of Soyuz-T 10. This time the crew numbered three due to the inclusion of a physician, Dr. Oleg Atkov, who would monitor the long – duration crew (EO-3) of Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov during their record attempt. Kizim and Solovyov had been trained for several EVAs to attempt to fix the leaking fuel tanks. Eventually they would carry out a record six spacewalks in their efforts to fix the leaks and add solar arrays to the station. Salyut 7’s future had been assured by the skillful efforts of the cosmonauts and wisdom of the planners on the ground. Two crews of visiting cosmonauts included the first Indian in space Rakesh Sharma, and the return of Svetlana Savitskaya who would make a spacewalk this

|

Soyuz-T 13, Salyut 7 repair crew |

time. Savitskaya was accompanied by Buran chief test pilot Igor Volk, who was using this flight to test a home coming Buran pilot’s ability to land his craft on a runway at the end of a long flight. Upon landing on 29 July, Volk immediately flew a MiG fighter to 21 km before landing with dead engines to simulate a Buran landing. The three-man EO-3 crew landed on the 2 October having set a new duration record of 237 days in space, which would be the longest single-crew stay aboard Salyut 7. Vladimir Dzhanibekov, who had commanded the Soyuz-T 12 mission with Savitskaya and Volk, could not have had any idea that he would be returning to the station in less than a year, or why.

The year 1985 was to be a somewhat more complicated and dramatic year for Salyut 7 and its crews. It began when Mission Control lost all contact with the station on 11 February; it had lost all attitude control and had gone into free drift mode, making it impossible for a Soyuz ferry to automatically dock with the station. The crew of Soyuz-T 13 were dispatched on 6 June with Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Viktor Savinykh to try and determine what had gone wrong. When they rendezvoused, the station appeared to be undamaged, although it was clearly without power, there being no lights, and the solar arrays pointing in differing directions. The station was slowly rolling around its long axis, but Dzhanibekov was able to line up the Soyuz with the aid of docking controls that had been installed in the orbital module for just such a purpose. They managed to dock, and entered the dead station; it was dark and cold as it had been completely powered off. By the crews own crude estimate, the interior temperature was about — 10°C, an estimate reached by spitting on the bulkhead and timing how long it took to freeze! Clearly, they would have to wrap up to work in these conditions, and return intermittently to the Soyuz to warm up. To attempt to bring the station back to life, the crew fitted spare batteries, replacing the existing ones that would not charge back up. In the process of this work they discovered a faulty charge sensor. This sensor determined if a battery was full or in need of charging, and it had failed in such a way that the computer thought that all of the batteries were fully charged and stopped trying to charge them; as a result all of the batteries went flat, and the station died. If a crew had been on board, the faulty sensor would have been immediately detected, and replaced well before the station lost all power. Once this sensor was replaced, the task of recharging the batteries began, and the station slowly came back to life. The crew had saved the station, once again proving the value of humans in space, and proving that the Soviets were now very comfortable with repairing their spacecraft, rather than just launching new ones when something went wrong. A fact that they would be keen to underline when failures began to undermine the fledgling partnership with NASA.

Soyuz-T 14 arrived on 18 September with Georgi Grechko, Vladimir Vasyutin, and Aleksandr Volkov aboard. Vasyutin and Volkov had trained with Savinykh as the original long-duration (EO-4) crew, so when Soyuz-T 13 landed on 26 September it left behind the EO-4 crew to begin their mission. Unfortunately, during October Vasyutin became very ill; his temperature was very high (about 40°C), and the ground advised him to rest in the hope that the fever would pass. It did not get any better; in fact he seemed to get worse, and Valeriy Ryumin ordered an immediate end to the mission. In actual fact, it took the crew about a week to prepare the station for autonomous flight and return to Earth, by which time Vasyutin had become very ill indeed. Upon his return he was immediately taken to hospital, where he took a month to recover from what turned out to be a prostate infection. It was an unfortunate end to a promising long-duration mission by Savinykh, who was very disappointed to have missed the duration record. It was also unfortunate for the future of Salyut 7, which had clearly reached the end of its useful life. The rescue mission had also used a Soyuz that was to have been utilized by an all female crew commanded by Svetlana Savitskaya with two flight engineers Yekaterina Ivanova and Yelena Dobrokvashina. After the cancelation of their flight it was hoped that they might fly to Mir, but Savitskaya became pregnant in 1986, and the idea was abandoned. Ivanova and Dobrokvashina were never assigned to another mission, and both left the cosmonaut corps in 1993.

The EO-4 mission was to be the last planned long-duration flight to Salyut 7; its successor Mir had been launched on the 19 February 1986, and it seemed as if Salyut 7’s operational life was over. However, a unique mission was planned that would see the crew of Soyuz-T 15, Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov, activating the new Mir station, and then flying their Soyuz to dock with Salyut 7 to complete and collect the work not finished by the EO-4 crew. So on 5 May they undocked from Mir after six weeks aboard and transferred to Salyut 7 the next day. After 50 days aboard Salyut 7 they returned to Mir for a further 25 days before returning to Earth on the 16 July after a truly unique mission.

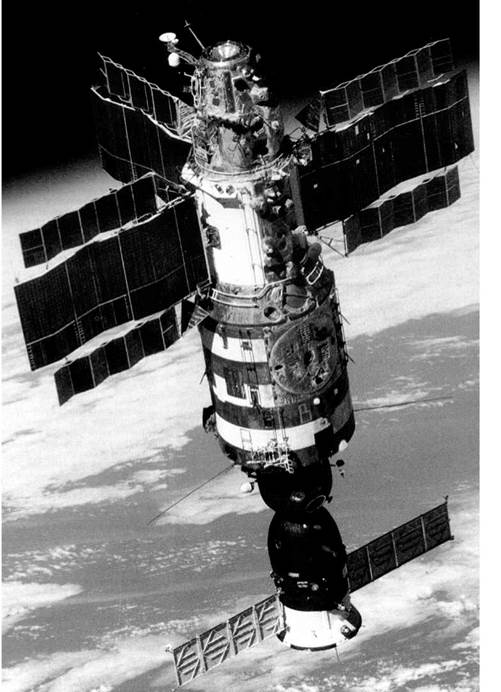

|

Salyut 7 in orbit |

Salyut 7 stayed in orbit until 7 February 1991 when it re-entered the atmosphere and was destroyed. The stage, however, had been set, for Mir was now operational and offered much more flexibility than the previous Salyut stations. The best was yet to come.