1971: Salyut 1—triumph and disaster

The successful launch of Salyut 1 on 19 April 1971 was a truly historic event. Salyut had not always been its name, indeed the word Zarya was written on the side of the station. Just before launch the official name became Salyut, apparently to prevent confusion with a ground station already named Zarya. After so many years of dreams and plans, humankind had an orbiting space station, and it was ready to accept its first crew. The launch was particularly noteworthy for the Soviets as it came a full two years before America could launch its planned Skylab. This had been one of the main motivations behind combining the Almaz design with Korolev’s Soyuz ferry vehicle. As with many of the Soviet’s spaceflight achievements, political considerations had pushed the space station program forward faster than it might have on its own. This first station was not huge, weighing about 18 tonnes and measuring 20 m in length, and certainly not luxurious, but it represented a milestone in manned space exploration.

The crew of Soyuz 10 would be the first to inhabit this new outpost in orbit. The crew comprised commander Vladimir Shatalov, flight engineer Aleksei Yeliseyez, and researcher Nikolai Rukavishnikov. They were launched four days after Salyut 1 had successfully made orbit, and rendezvoused with the station shortly after. The docking was carried out without any problems, Shatalov having exploited his previous experience of docking Soyuz 4 and 5. Unfortunately, despite a hard docking having been achieved, the crew were unable to swing back the Soyuz docking probe that had to be removed before the crew could access the tunnel that joined the two craft. It was later determined that a failure in the Soyuz docking port’s electrical system had caused the problem. The crew of Soyuz 10 had no choice but to undock from the station and return home, having filmed the Salyut docking port for later analysis on the ground.

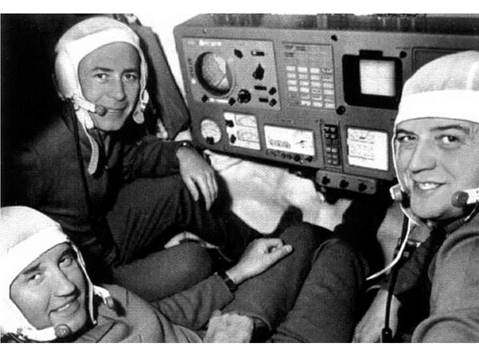

The back-up crew for Soyuz 10 consisted of commander Alexei Leonov, with flight engineers Valeri Kubasov and Pyotr Kolodin, and they were now advanced to the prime crew for Soyuz 11. For Leonov this was a significant event. In the three

|

Soyuz 10 back-up crew |

|

Soyuz 11 crew |

years following the historic Voskhod 2 flight that had made him the first human to walk in space, he had been training for a flight around the moon in a Zond spacecraft. The flight of Apollo 8 in lunar orbit in December 1968 and a less than successful unmanned test of Zond, had led to his flight being canceled. Ultimately, the entire Soviet manned lunar program was canceled, and Leonov was promoted to lead the training of cosmonauts for the Salyut program. However, fate was to intervene in Leonov’s career once more when Kubasov developed a lung infection shortly before launch. This was later determined to simply be an allergic reaction, but that did not help Kubasov at the time; he was removed from the Soyuz 11 crew and replaced with Vladimir Volkov, his back-up. Then, just eleven hours before launch, it was decided to replace the entire Soyuz 11 crew as a precaution against Kubasov’s lung infection having been passed on to the rest of the them. Leonov was replaced by Gyorgy Dobrovolsky, and Kolodin by Viktor Patsayev. Volkov remained on the crew. The replacement crew for Soyuz 11 were as shocked as Leonov by the decision. They had only been training together for a few months, and had not expected to be launched on an actual mission for several more months, and were concerned that they were not ready. Leonov’s crew were sent away for a holiday before they began training for a flight to Salyut 1 upon the return of Soyuz 11.

The launch, rendezvous, and docking of Soyuz 11 all went smoothly, and the crew were able to enter the station with none of the problems that had affected the previous flight. Despite their concerns and relative lack of training, the flight proceeded well for 12 days until 18 June when the smell of burning was detected and a small electrical fire was found. The crew were very alarmed by this and urged the ground controllers to let them evacuate the station and return to Earth. In preparation, they powered up the Soyuz ferry vehicle, but returned to the station when it was realized that the danger had passed. Nevertheless, this incident had badly dented their morale, and although they continued their work, it was with less passion and drive than before. After a week, the ground controllers decided to let the crew come home early, and on 29 June they packed the Soyuz for the return trip. Their mood was significantly lifted as they strapped themselves in and undocked from Salyut 1, thereby bringing to an end the first mission to a manned space station, which had originally been planned to last 30 days, but was cut short to 23 days.

The Soyuz re-entered the atmosphere as expected and parachuted to a soft landing on the steppes of Kazakhstan. The recovery team opened the hatch to find all three men dead in their couches.

The Soviet people were horrified by the deaths of three brave men that they had come to know well from their nightly broadcasts from the Salyut station, and they now mourned their loss as they would a family member. The crew were interred in the Kremlin wall alongside other space heroes such as Yuri Gagarin, Sergei Korolev, and Vladimir Komarov. The inquest soon determined that a pressure relief valve designed to equalize the internal pressure in the capsule as it descended through the atmosphere had opened prematurely, possibly when the explosive bolts that separated the descent module from the orbital and propulsion modules were fired after the de-orbit burn, prior to entry into the atmosphere. It would probably have not been immediately apparent to the cosmonauts that the valve had opened; and even if it had, the

|

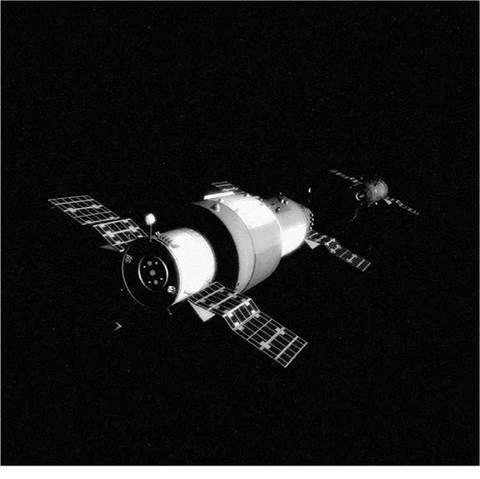

Soyuz 11 undocks from Salyut 1 (computer image) |

valve was not easily accessible by the crew, although there was evidence to suggest that they had tried to stem the flow of air from their craft. This failure would not have been a problem except for one important fact, the crew did not have pressure suits; Soyuz crews simply wore flight overalls. As the pressure inside their capsule vented, the crew slowly lost consciousness, and eventually died from embolisms in the blood due to the vacuum. The Soyuz landed automatically as if nothing was wrong. Alarm bells rang throughout the spaceflight community. NASA even contacted the Soviets to determine if the long duration of their mission had been a factor in their deaths. Clearly, changes needed to be made to the Soyuz design to prevent a future catastrophe, and Salyut 1 would not be able to be inhabited in its lifetime again, so it was commanded to de-orbit by firing its engines to initiate a ditching in the Pacific Ocean in October 1971.

The redesign of the Soyuz spacecraft turned out to be substantial. It was clear that in the future cosmonauts must launch and land wearing pressure suits, and this would require more room than was currently available in the descent module. The only way to accommodate the newly designed Sokol K1 spacesuits, along with the extra equipment needed to support the space-suited crew would be to remove one man from the Soyuz configuration. This had implications for future space station designs, as a crew of two would obviously have more work to do. The Soyuz 11 crew had spent much of their 23 days aboard Salyut 1 simply looking after the station’s systems; two men would be even more pressed to keep up with a station’s needs.

Alexei Leonov was assigned to command the first crew to occupy the next Salyut station, along with Valeri Kubasov, but his luck was to betray him again. The next Salyut was actually the back-up for the Salyut 1 mission, and therefore identical to its predecessor. Unfortunately, only two and a half minutes after launch on 29 July 1972 one engine on the Proton rocket’s second stage failed, and the vehicle crashed into the Pacific Ocean, taking the Salyut with it. Officially it was never called a Salyut or anything else; only in later years would it become apparent that this launch had taken place.