AFTERWORD

|

T |

he 199th flight by Bill Dana in 1969 was the last for the X-15. The two of these revolutionary airplanes that still remained were readied for installation in national aviation museums after the completion of the X-15 research program.

As early as 1962, the Smithsonian Institution had requested an X-15 airplane for eventual display in Washington, D. C. The first X-15 was installed by the Smithsonian on May 13, 1969, in what was then known as Silver Hill and is now called the Garber Facility. It was moved to the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building in June 1969 and placed near the 1903 Wright Flyer. The Arts and Industries Building served as the National Air and Space Museum at that time. After being loaned out to the FAA and then to the NASA Flight Research Center for display, it returned to the Smithsonian to be installed in the new National Air and Space Museum in Washington, on the Mall, for its opening on July 1, 1976. It hangs there now in the Milestones of Flight Gallery.

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|||

The X-15A-2 airplane went to the National Museum of the USAF at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. A set of external tanks and a dummy supersonic combustion ramjet (scramjet) engine are part of that display.

The X-15-3 that crashed with Mike Adams was buried at an unknown location at Edwards Air Force Base.

The two B-52 carrier airplanes used by the X-15 program were reassigned by the Air Force after performing in the subsequent lifting body program at the NASA Flight Research Center. The X-15 pilots continued with their careers: Neil Armstrong became famous as one of the first three men to land on the moon. Selected to be in the second astronaut class, he left the X-15

program, commanded Gemini 8, and on July 20, 1969, as commander of Apollo 11, became the first human to walk on the moon. His next position in NASA was deputy associate administrator for aeronautics at NASA headquarters. He left NASA to become professor of aeronautics at the University of Cincinnati, after which he served on the boards of several corporations. Neil Armstrong passed away on August 25, 2012.

program, commanded Gemini 8, and on July 20, 1969, as commander of Apollo 11, became the first human to walk on the moon. His next position in NASA was deputy associate administrator for aeronautics at NASA headquarters. He left NASA to become professor of aeronautics at the University of Cincinnati, after which he served on the boards of several corporations. Neil Armstrong passed away on August 25, 2012.

Bill Dana became chief pilot at the Flight Research Center, then had progressively higher positions in Flight Operations, in F-18 research, and finally as chief engineer at the Flight Research Center, a position he held until his retirement in 1998.

Joe Engle was selected to become an astronaut in 1966 and performed as support crew on Apollo 10, then as backup lunar module pilot on Apollo 14. He commanded the Space Shuttle Columbia

and manually flew the reentry from Mach 25 through reentry and landing (the only time it was manually flown for an entire flight). His last flight in space was as pilot of Discovery in August 1985.

Pete Knight went to Southeast Asia and flew 253 combat missions in the F-100. He was test director of the F-15 System Program Office and piloted the airplane. He returned to Edwards Air Force Base as vice commander of the Flight Test Center and as an active F-16 pilot. He retired from the Air Force in 1982 and entered politics, rising to California state senator. He died on May 8, 2004.

Jack McKay retired from NASA in October 1971 and died on April 27, 1975, largely from complications from his X-15 crash.

Pete Peterson left NASA in 1962 and returned to the U. S. Navy, rising in rank after combat in Vietnam to be commander of the Naval Air Systems Command. He retired from active duty as vice admiral in May 1980. He died on December 8, 1990.

Bob Rushworth returned to the USAF after flying the X-15, and in the Vietnam conflict he flew 189 combat missions. He rose through the command ranks to become a general, and he retired as a major general from the position of vice commander of the Aeronautical Systems Division at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. He died of a heart attack on March 17, 1993.

Milt Thompson remained with NASA after piloting the X-15, becoming chief of research projects. He then became chief engineer, a position he retained until his death on August 6, 1993. He wrote a wonderful book about his experiences flying the X-15, At the Edge of Space.

Joe Walker was helping obtain publicity shots of the XB70A while flying an F-104. Getting too close to the B-70 and caught in air currents between the two aircraft, he was killed in a midair collision on June 8, 1966.

Bob White continued in the United States Air Force. He became brigadier general and

commander of the Air Force Flight Test Center. He later became a major general and then chief of staff of the 4th Allied Tactical Air Force. He retired from the USAF in February 1981 and died on March 17, 2010.

Scott Crossfield, who left the NACA Flight

Research Center to join North American Aviation

to be a part of their X-15 design and flight-test team, ended his association with the X-15 program when the Air Force took it over. He then continued at NAA in many high-level and technical executive positions. He followed his NAA career with executive positions at Eastern Airlines and Hawker Siddeley Aviation. He then became a consultant to the House of Representatives Committee on Science and Technology. He lectured on aviation to many groups until his demise. It was after such a lecture at Maxwell AFB that he was killed in his Cessna 210 aircraft in a storm over Georgia while flying home on April 19, 2006.

At this writing, Joe Engle and Bill Dana are the only surviving X-15 pilots.

Collectively, the pilots who flew the X-15 airplane continued in their careers, flying for NASA in a research mode or for the military, where they progressed into positions of military leadership. Building upon their technical backgrounds and research piloting, they applied their work discipline to perform important responsibilities on behalf of the United States.

They were talented men, driven and successful in their endeavors.

The X-15 remains the fastest and highest – flying manned airplane in history. The fact that no

Test pilot Scott Crossfield in his pressure suit standing with colleagues in front of the B-52 mother ship. USAF, Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, Edwards Air Force Base

Joe Walker ready to enter the cockpit for his first flight on the X-15, March 25, 1960. This was the first government flight in the X-15 program. USAF, Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, Edwards Air Force Base

other manned hypersonic airplane has followed in its wake is a testimonial to the difficulty and severity posed by the hypersonic flight regime. The authors remain convinced that the future will see manned hypersonic flight for sustained periods in the atmosphere, a development that will rely on the data produced during the X-15 program on hypersonic aerodynamics, flight dynamics, structures, flight control, and pilot behavior. These hypersonic airplanes will be powered by airbreathing jet engines, not rocket engines. Such airbreathing engines will be supersonic combustion ramjet engines (scramjets), which have been under development since the 1970s and which are still a subject of intense research.

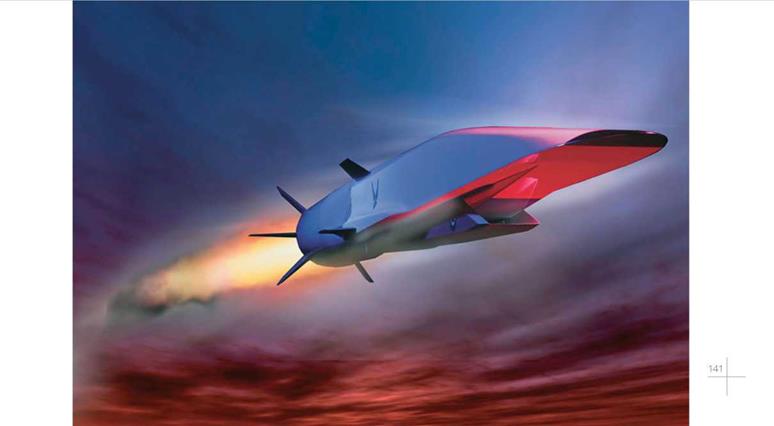

Indeed, on May 1, 2013, the experimental X-51, an unmanned hypersonic vehicle, achieved the longest duration sustained flight powered by a scramjet of over 300 seconds at speeds above Mach 5. The future of practical, environmentally safe, and economically feasible hypersonic manned flight still lies before us, and when that happens, the X-15 will indeed be the “Wright Flyer” of its kind.

▲ X-15 in flight. USAF, Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, Edwards Air Force Base

▼ The X-51 hypersonic research vehicle, powered by a supersonic combustion ramjet engine (scramj et). The X-51 is unmanned and is a waverider configuration for high lift-to-drag ratio. Its first flight was on May 26, 2010. Its fourth and final flight was on May 1, 2013, when it flew at Mach 5.1 for 240 seconds under scramjet

propulsion, the longest air-breathing hypersonic flight to that time. USAF