ROBERT A. RUSHWORTH

1924-1993

Bob Rushworth was the workhorse test pilot for the X-15, with thirty-four flights, more than the next most frequent flyer, Jack McKay, who flew the X-15 for twenty-nine flights. Rushworth set the high-speed record for the X-15-1 (the first X-15) on December 5, 1963, achieving Mach 6.06.

Bob Rushworth was born on October 9, 1924, in Madison, Maine. During World War II, he joined the Army Air Forces and flew C-46 and C-47 transports. He was called back into the Air Force to fly combat missions during the Korean War, after which he made the Air Force his career. He had graduated from Hebron Academy in 1943, and he continued his education at the University of Maine, where he received his bachelor of science degree in mechanical engineering in 1951. He followed this with a degree in aeronautical engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT) in Dayton in 1951. Much later, after completing his service as an X-15 test pilot, he graduated from the National War College at Fort McNair in Washington in 1967.

After receiving his AFIT degree in aeronautical engineering, Rushworth stayed at Wright Field in Dayton to start a flight-test career. In 1956, he was transferred to Edwards Air Force Base, where he graduated from the Experimental Test Pilot School just in time to join the X-15 program in 1958. His first flight in the X-15 was on November 4, 1960, an uneventful pilot-familiarization flight to obtain stability and control, and performance data, at Mach 1.95 at 48,900 feet. Rushworth was

Three X-15s were built and were unofficially labeled by people in the program as Ship 1,

Ship 2, and Ship 3. (This harks back to the early twentieth century when sometimes airplanes were referred to by the name of “ship.”) The official labels of the three X-15s were X-15-1, X-15-2 (later renamed the X-15A-2 after extensive modifications following an accident midway through the flight program), and X-15-3.

|

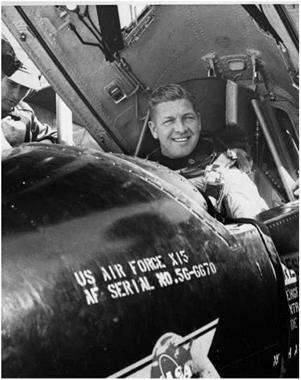

Rushworth in the X-15-1. USAF, Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, Edwards Air Force Base |

|

|

|

to fly thirty-three more times in the X-15, during which he achieved a maximum Mach number in the X-15-1 of 6.06, as noted earlier. Other accomplishments included the first ventral-off flight on October 3, 1961, and the highest dynamic pressure of 2,000 pounds per square foot (an aerodynamic high point that tested the structural integrity of the X-15) on May 8, 1962. When he attained an altitude of 285,000 feet on June 27, 1963, he qualified for Astronauts Wings.

Rushworth encountered numerous problems during his test flights. The right inner windshield

cracked during his Mach 6.06 flight, and it happened again six months later on May 12,

1964, after achieving Mach 5.72 and an altitude of 101,600 feet. On September 29, 1964, after achieving Mach 5.2, the nose gear scoop door came open at Mach 4.5 and 88,000 feet. Later, Rushworth calmly noted that the X-15 handled worse in that configuration than with the nose gear fully extended. On February 17, 1965, his right gear extended at Mach 4.3 at 85,000 feet, his inertial altitude indicator failed, and he momentarily lost engine power 23 seconds into the

|

|

|

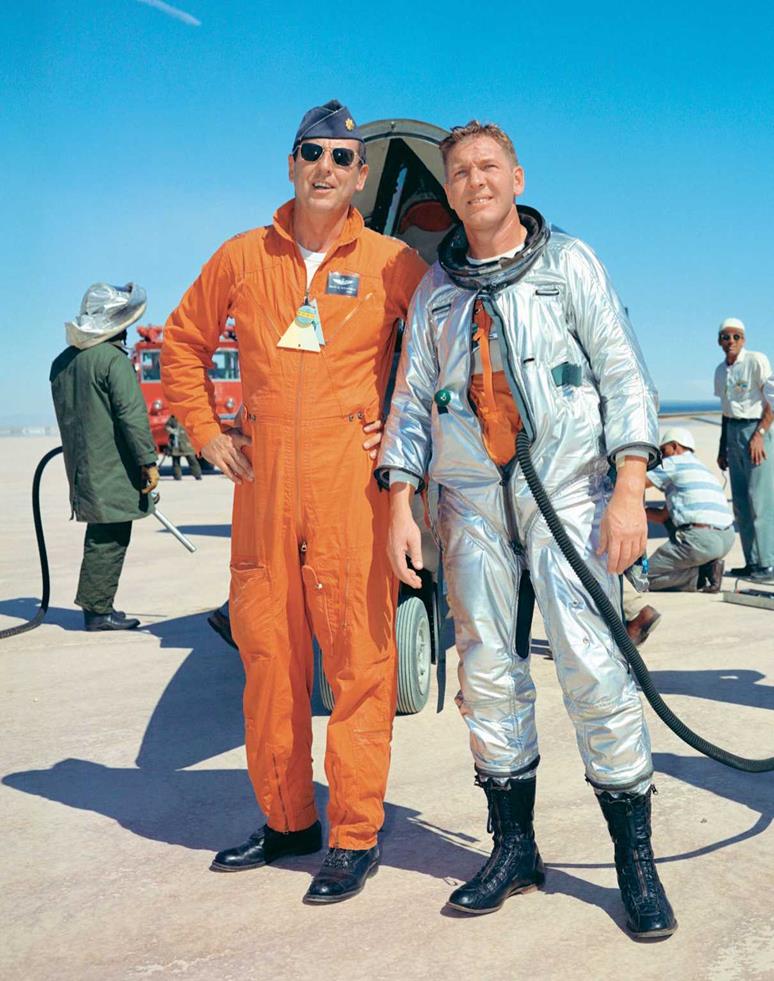

Rushworth after an X-15 flight. USAF, Air Force Flight Test Center Flistory Office, Edwards Air Force Base |

flight. Despite all this, he continued with the flight, attaining Mach 5.27 at 95,000 feet and carrying out his test mission of stability and control evaluation, star tracker checkout, and advanced landing dynamics.

Rushworth’s last flight in the X-15 was on July 1, 1966, the 159th flight of the program, and again not without excitement. An indication of no propellant flow from one of the external tanks carried during that flight caused him to eject the external tanks and land prematurely, as he stripped off the top of a camper upon landing at Mud Lake.

Perhaps one of Rushworth’s most important contributions to the X-15 program was on the ground. Milton Thompson notes that because it was not a combat aircraft, the X-15 had low priority within the Department of Defense, and it was mainly due to Rushworth’s efforts that the X-15 schedule was reasonably maintained.

After leaving the X-15 program, Bob Rushworth moved to F-4 Phantom combat crew training at George AFB, and then assignment to Cam Ranh Bay Air Base in Vietnam as the assistant deputy commander for operations with the 12th Tactical Fighter Wing, where he flew 189 combat missions. He returned to the United States in 1969 as program director for the AGM-65 Maverick missile, and he became commander of the 4950th Test Wing at Wright-Patterson AFB in 1971. Two years later, he was inspector general for the Air Force Systems Command, and in 1974 he returned to Edwards as commander of the Air Force Flight Test Center. In 1975, he became commander of the Air Force Test and Evaluation Center at Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico. He was promoted to Major General on August 1, 1975. He retired from the Air Force in 1981 as a general and as vice commander of the Aeronautical Systems Division at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

On March 18, 1993, Bob Rushworth died of a heart attack in Camarillo, California. He left behind a stellar career as a test pilot and Air Force officer, and his expert handprints are all over the X-15 program.

NEIL A. ARMSTRONG

1930-2012

Neil Armstrong, by virtue of being the first man to step foot on the moon, is known and respected worldwide.

Armstrong was in many ways an anomaly among the X-15 test pilots. Following in the steps of Bob Rushworth, who flew the X-15 a total of thirty-four times, seventh X-15 pilot Armstrong made only seven flights in the airplane. Like Scott Crossfield, Neil Armstrong was first and foremost an aeronautical engineer. Even when he was working with NASA as a test pilot, he was known as one of their best engineering minds. Much later,

he said about himself, “I am, and ever will be, a white-socks, pocket-protector, nerdy engineer— born under the second law of thermodynamics, steeped in the steam tables, in love with free-body diagrams, transformed by Laplace, and propelled by compressible flow.”

he said about himself, “I am, and ever will be, a white-socks, pocket-protector, nerdy engineer— born under the second law of thermodynamics, steeped in the steam tables, in love with free-body diagrams, transformed by Laplace, and propelled by compressible flow.”

Neil Armstrong was born on August 5, 1930, in Wapakoneta, Ohio. His interest in airplanes can

be traced back to the time when his father took him to the Cleveland Air Races when he was only two years old. When he was five, his father took him for his first airplane flight in Warren, Ohio, on a Ford Trimotor. Neil took flying lessons while attending high school, and he earned his flight certificate at the age of fifteen, before he had a driver’s license. He became an Eagle Scout, and for the remainder of his life he was a dedicated supporter of the Boy Scouts. (Among the few personal items that he carried with him to the moon was a World Scout Badge.)

In 1947, Armstrong began studies in aeronautical engineering at Purdue University, but he was interrupted by the Korean War. Armstrong became a Navy pilot, flying F9F Panthers for seventy-eight missions over Korea and achieving the Air Medal, the Gold Star, and the Korean Service Medal, all before the age of twenty-two. After leaving the Navy, he returned to Purdue and received his bachelor of aeronautical engineering degree in 1955. He joined NACA as an experimental research test pilot at the Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, and he then moved to the NACA High Speed Flight Station (now the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center) as an aeronautical research scientist and test pilot. It was there that he attended the University of Southern California, earning a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. And it was there that he became involved with the X-15 program as a test pilot.

Armstrong’s first flight in the X-15, the usual pilot-familiarization flight, took place on November 30, 1960, when he reached Mach 1.75 and an altitude of 48,840 feet. The upper No. 3 chamber of the rocket engine did not start, and the readout of inertial altitudes was incorrect.

His second flight came nine days later, when he evaluated a new ball nose for the airplane and measured stability and control data. His third flight was not until almost a year later, on

![]() The X-15 was equipped with an air data inertial reference unit (ASIRU), which provided measurements based on air pressure, airspeed, angle of attack and altitude, and measurements based on inertial reference (accelerometer plus computer) of position and altitude. Hence, the altitude of the X-15 was measured using two separate techniques.

The X-15 was equipped with an air data inertial reference unit (ASIRU), which provided measurements based on air pressure, airspeed, angle of attack and altitude, and measurements based on inertial reference (accelerometer plus computer) of position and altitude. Hence, the altitude of the X-15 was measured using two separate techniques.

Radar data from the ground provided a third measurement of altitude.

(See NASA TM X-51000, The X-15 Flight Test Instrumentation, by Kenneth C. Sanderson, presented at the Third International Flight Test Instrumentation Symposium, Buckinghamshire, England, April 13-16, 1964.)

December 20, 1961, when he carried out the checkout flight of the No. 3 airplane.

On April 20, 1962, Armstrong carried out the longest flight of the X-15 program, a duration of 12 minutes and 28 seconds. On this same flight, he achieved his highest altitude, 207,500 feet. On his return, Armstrong inadvertently pulled too high an angle of attack during pullout. The flight path took a bounce in the atmosphere, and he overshot the Edwards Air Force Base, heading south at Mach 3 and at 100,000 feet. He was able to turn back while over the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. Almost out of kinetic and potential energy, he was just barely able to reach the south end of Rogers Dry Lake at Edwards.

Armstrong’s fastest flight in the X-15 was on July 26, 1962, when he achieved Mach 5.74. This was also his last flight in the airplane, because on September 13 he was selected for the Astronaut Corp by NASA, making him at that time the only civilian pilot in the astronaut program. With that, Armstrong’s career took a dramatic turn, culminating in his steps on the moon. The date was July 21, 1969, less than a year after the X-15 program came to an end.

After his Apollo 11 flight, Armstrong chose not to fly in space again. In 1971, he resigned from NASA and took a position with the University of Cincinnati as the distinguished university professor of aerospace engineering. He taught for eight years and then resigned without explaining his reason for leaving. He withdrew from public life and refused most speaking invitations. On August 7, 2012, in Cincinnati, he underwent bypass surgery for blocked coronary arteries. He died on August 25 from complications. Based on his request, his ashes were scattered in the Atlantic Ocean during a burial-at-sea ceremony aboard the USS Philippine Sea.