Traveling in Space

After being launched, a spacecraft leaving Earth for the Moon or Mars does not need to keep burning fuel. Spacecraft can make use of other methods of propulsion, such as solar sails or ion engines. Once on course and free of Earth’s gravity pull, the engines can be switched off to save fuel as the spacecraft coasts through space. This is how the Apollo astronauts traveled to the Moon, a trip that took two-and-a-half days. They fired their engines only to slow down the spacecraft and during their return to Earth.

|

О The Apollo 10 crew sped home at 24,790 miles per hour (39,890 kilometers per hour) on their return from the Moon in 1969. The astronauts’ capsule splashed down safely in the Pacific Ocean. |

|

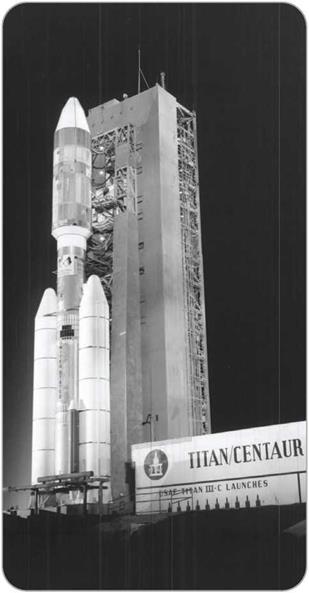

О Helios A and Helios B were space probes sent in the 1970s to orbit the Sun. They reached the highest speed of any spacecraft. A 1974 photograph shows Helios A on top of a launch vehicle. |

Although there is no air in space, space is not empty. It contains dust, chunks of minerals, space junk, and streams of radiation flowing out at great speed from the Sun and from other stars.

Stretching into space around Earth is a magnetic field. This magnetism attracts electrically charged particles that form belts, or zones, of radiation. Named the Van Allen radiation belts, these radiation zones were unknown until the first U. S. satellite, Explorer 1, encountered them in 1958. The Van Allen belts were the first important scientific discovery made by a spacecraft.

The fastest spacecraft sent from Earth so far have been the solar probes Helios A (1974) and Helios B (1976). Helios B traveled about 150,000 miles per hour (241,350 kilometers per hour) as it orbited the Sun. Although spacecraft are the fastest vehicles ever flown by humans, they are snail-like in space terms, where the distances are unimaginably immense. The nearest star is 4.2 light years from Earth. So even if a future spacecraft could reach light speed of 186,000 miles per second (299,280 kilometers per second), it would take 4.2 years to get there.

To fly astronauts to Mars and back using existing spacecraft would take eighteen months. Keeping astronauts alive, healthy, and able to work during such a long mission poses great challenges to space science. Humans are not designed for an airless, weightless environment. A manned spacecraft must provide everything needed for human life support-air, water, food, fuel, energy, waste disposal, and exercise. Long periods of spaceflight weaken the body’s muscles. So great are the challenges that some scientists believe that