Operations of the Last Piston-Engined Night Fighters

During the last phase of the war, to the beginning of 1945, the air defence of the Reich fell within the jurisdiction of Luftflotte Reich, under whose umbrella came Jagddivisionen 1 (Doberitz), 2 (Stade), 3 (Wiedenbriick) and 7 (Pfaffenhofen) together with Jagdfiihrer (Jafu) Mittelrhein (Darmstadt) and numerous Luftwaffe signals units. Despite an efficient radio control system, even at night the crews failed to achieve the expected successes. Why?

The Allies had a huge reserve of bomber aircraft. The ability to deploy over a thousand aircraft in a single night raid far exceeded the Luftwaffe defensive capacity. Even raids with far fewer bombers proceeded with impunity and devastating effect. On the night of 29 January 1945, for example, 606 RAF heavy bombers inflicted serious damage on Stuttgart for only eleven losses to night fighters and flak.

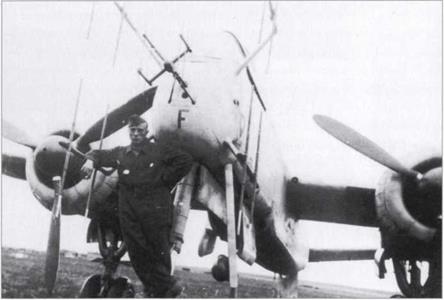

|

These Ju 88 G-l night fighters were attached to NJG 3. They were armed with four fixed 2-cm guns and along with the Ju 88 G-6 were standard aircraft for the night air defence role. |

|

The Allies were able to jam the German Lichtenstein radar (FuG 220) to such an extent that the sets had to be replaced by other types, as for example the FuG 240. The installation is seen here in the nose of a Ju 88 G-7. |

At the beginning of 1945 the Wehrmacht was operating with only 28 per cent of the fuel stock it had in January 1944. Ever heavier air raids on the production centres of aviation fuels had cut Luftwaffe supplies to 6 per cent of the previous years figure for January. In late 1944 Luftwaffe operational units were living for a while on their meagre fuel reserves, and night-fighter sorties were only flown if the occasion looked particularly favourable. Night-fighter Gruppen in 1945 might have 30 machines, mainly Bf 110 G-4s and Ju 88 G-6s, at readiness but probably only five, exceptionally ten would be committed. It is therefore not surprising that of 6,600 RAF bombers over the Reich in January 1945, only 1.4 per cent, fewer than 100, came to grief. The Luftwaffe Command Staff could see a greater debacle in the offing for the night fighter arm, and on 3 February 1945 they disbanded the Jafii Groups in East Prussia, Silesia and Hungary once they came under threat as the enemy advanced.

The remorseless RAF Bomber Command operations continued nightly, and British aircrew found it increasingly common to have little or no Luftwaffe opposition. From the beginning of 1945, the Luftwaffe experimented with new groupings and unit interchange apparently in the hope of improving its performance at night. OKL, recognising that supplies of fuel were limited and the level of operations could not be raised by dipping into the fuel reserves, decided on another tack by selecting which crews would fly. On 24 February aircrew were assessed into categories T, ТГ and ‘Others’. The last were employed on transfers or workshop flights, their machines being parked on the edge of airfields under camouflage. From the end of February, Class I veteran crews with numerous victories were those mainly used on operations, and proportional to the machines committed far more kills were achieved than before.

Allied electronic jamming methods were considered first-class. The years spent rejecting centimetric technology had led the once powerful German night- fighter arm into a blind alley. Moreover, from March 1945, more and more airfields were abandoned as the Western Allies reached the Rhine-Main area, the units dispersing to north and south Germany to guarantee further operations.

The last great night-fighter operation ensued on 21 March when 89 crews opposed an RAF raid on the hydro-electric plant at Bohlen-Altenburg. Aircraft of Jagddivisionen 1 and 3 and the Mittelrhein Jafii were involved in the pursuit which resulted in at least 14 bombers being shot down. At the end of the month night-fighter operations were cut drastically as fuel stocks vanished with no fresh supplies expected now that communications to storage dumps had been severed. Despite the fuel situation OKL manoeuvred individual squadron units in an attempt to continue the struggle. An OKL order to disband part of each Staffel reduced all surviving night-fighter Gruppen to a maximum of 16 aircraft, while the now superfluous Geschwader – and Gruppenstabe were disbanded. These were to be replaced by autonomous Einsatzgruppen (Operational Groups), each with a Gruppenstab, four Staffeln and a Stabsstaffel. Because of the deteriorating situation on the ground this instruction was dubious from the start.

|

One of the best night fighters of the Luftwaffe was the He 219. Work continued on the He 219 A-7 at Vienna-Schwechat until almost the end of the war. |

|

Dr Hiitter’s design for a night fighter and long range reconnaissance aircraft, the Hu 211, was developed from the He 219. It was better aerodynamically with a greater wing surface. |

At unit level, flight organisation had long been dictated by the realities. On 11 April, 20 twin-engined night fighters took off to engage RAF heavy bombers for the last time, and after that operations ebbed. The majority of the command centres had been dissolved, and the Allies had cut the Reich into two at the midriff. In northern Germany and Denmark, Luftwaffenkommando Nord controlled night-fighter operations, which amounted to more or less well-led individual missions. Day and night-fighter operations over Bavaria, Austria and the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were headed by Luftwaffenkommando West. As the supra-regional command structure and operational control crumbled away in the last weeks of the war, the Geschwader were placed in an extremely difficult positions when enemy bomber streams arrived and then often split to attack several targets.