In China’s Backyard, the PLAAF’s SAMs Weigh Heavily

In almost any plausible near – to mid-term Sino-U. S. confrontation, China would have home-field advantage, at least relative to the United States. Whether across the Taiwan Strait, over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, or in the South China Sea, Beijing would be able to bring more of its military power to bear than could the United States. This is especially true in the early hours, days, and weeks of a conflict. For the PLAAF, that means that it will at least initially likely enjoy a numerical advantage over U. S. forces, and—depending on the circumstances— perhaps even over the combined forces of the United States and its partners.32

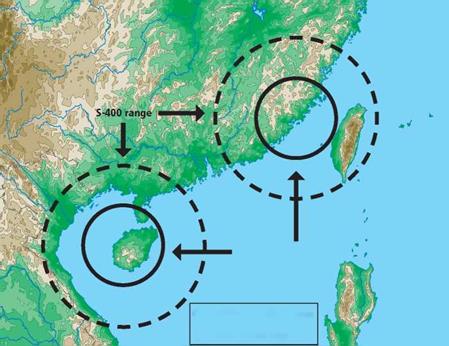

Operating close to China’s shores could also bring the PLAAF’s modern SAMs into the picture. Figure 8-3 shows the ranges of today’s S-300PMU2 (200 kilometers) and tomorrow’s S-400 (400 kilometers) in the context of the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea areas.33

At maximum range these missiles can engage only high-flying targets, but many important U. S. aircraft—the “force multipliers” described above along with high-endurance UASs like Global Hawk—typically operate at precisely those altitudes. Especially after the S-400 enters Chinese service, those U. S. platforms will either have to operate in the face of a much-increased SAM threat or fly farther away from the action and so compromise their perfor – mance.34 U. S. bombers carrying cruise missiles might be compelled to launch farther from the Chinese coast, which would limit the depth into the mainland that the missiles could reach. Closer in, these advanced SAMs could constrain the operation of even high-performance fighter aircraft; nonstealthy, so-called legacy jets—the F-15, F-16, and F/A-18—would be greatly at risk if called upon to fly within the S-300/400’s envelope.

Figure 8-3. Range Rings for S-300PMU2 and S-400 Surface-to-Air Missiles

Figure 8-3. Range Rings for S-300PMU2 and S-400 Surface-to-Air Missiles

S-300PMU-2 range

|

The Big Picture: The PLAAF Today and Tomorrow

If the PLAAF is not capable of challenging U. S. airpower in a nearby scenario like a Taiwan Strait contingency, its major items of equipment are no longer the main culprits. Its radical downsizing and steady modernization have, since 1995, brought the Chinese air force up to advanced world standards in many regards. Its growing fleet of fourth-generation fighters, stockpiles of advanced air-to-air and air-to-surface weaponry, emerging AEW&C and EW capabilities, and up-to-date surface-to-air defenses represent remarkable advances in technology and capacity since 1995.

In the event of a confrontation farther afield—for example, in the Malacca Strait, or closer to home, in the Spratly Islands—the PLAAF’s capabilities remain limited. Conducting high-tempo combat operations is much more challenging 1,500 or 2,500 kilometers from home versus 200 or 300 kilometers. Under these conditions, the PLAAF would require a much more robust in-flight refueling capability and enough AEW&C assets to compensate for the

absence of ground-based control. Recent years have seen the PLAAF begin to step up to the latter challenge; its intentions regarding tanker aircraft, on the other hand, appear modest. With only a dozen or so H-6Us operational and no known plans to acquire more than the four MIDAS tankers it ordered in 2005, aerial refueling does not appear to be a current priority for the Chinese; this will have to change if the PLAAF is to project significant power more than a few hundred kilometers from Chinese territory.

Looking toward 2020, it seems likely that the PLAAF will continue on the path it has been following since the mid-1990s. This will mean the retirement of many J-7s and early model J-8s accompanying the acquisition of additional advanced fighters. It seems unlikely that China will choose to replace its own “legacy” fighters on a one-for-one basis, so the PLAAF will probably continue to shrink, though not at the pace we have witnessed over the last 15 years.

The PLAAF’s decision to “indigenize” the Su-27 as the J-11B rather than build licensed Su-30s suggests a growing confidence in the ability of China’s defense industry to produce complex modern weapons. We might therefore expect to see a larger and larger proportion of Chinese-built hardware filling out the PLAAF’s inventory. We can also expect China to progressively upgrade its fourth-generation inventory to accommodate new weapons, radars, and avionics, as it already appears to have done with its Su-27s—to fire R-77/AA-12 MRAAMs—and the J—10, by developing the J-10B.

By 2020, the PLAAF may be operating at least small numbers of J—20 stealth fighters; we should also expect to see the introduction or enhancement of other PLAAF platforms and weapons. These include the following: more, and more advanced, AEW&C capabilities, and improved EW capacities overall; improved air-to-air weapons, including a very long-range AAM to threaten an adversary’s high-value assets like the E-3; the proliferation of “smart” weapons throughout the force; increased use of drones and UASs, likely including analogues to the U. S. Predator and Global Hawk aircraft; and continued deployment of the indigenous HQ-9 long-range SAM and acquisition of the S-400.

Although it seems less likely given available evidence, by 2020 China could also be well on the way to equipping the PLAAF with a new long-range strike aircraft to replace its antediluvian H-6s as bombers and cruise missile carriers. The PLAAF might also seek to increase its modest long-range airlift capabilities. Receiving the 34 Il—76 Candids it bought in 2005 would appreciably expand its transport fleet, but, as with tankers, the development and/or acquisition of more airlifters beyond those already booked would be needed if the PLAAF sought to support power projection over long distances.

The progress made in recent years by the PLAAF is impressive. Not too long ago, it was an unsophisticated congeries of ancient aircraft and weapons, its pilots poorly trained and poorly supported. As late as the early 1990s, it was likely too weak to have even defended China’s home airspace against a serious, modern adversary. In the early – to mid-1990s, as Chinese doctrine changed from focusing exclusively on territorial defense to contemplating limited power projection campaigns, the PLAAF found itself confronting a number of daunting learning curves that led from where it was to where it needed to be to fulfill its new missions. In terms of major items of equipment, it has successfully climbed many of these curves and appears at least to understand the ones that are left, even if it is not yet poised to climb them.

The revolution in the PLAAF’s order of battle is over. It has made up the four decades separating the MiG-17/MiG-19 generations from the Su – 27SK /Su-30MKK generation in just 15 remarkable years. Whether or not the PLAAF can close the remaining gaps between its capabilities and those of the most advanced air forces remains to be seen. But given how it has transformed itself over the last 15 years, one would be foolish to bet heavily against it.