Yakovlev Experimental Jet Fighters

Purpose: To create fighters and interceptors with new and untried features.

Design Bureau: OKB-115 ofA S Yakovlev, Moscow.

Yakovlev was one of the two General Constructors who created the first jet aircraft in the Soviet Union (the other was Mikoyan). Yakovlev cheated by, in effect, putting a turbojet into a Yak-3 ! A succession of single-engined jet fighters followed, one ofwhich was the Yak-25 of 1947 (confusingly, Yakovlev later used the same designation for a different aircraft, see later). This achieved the excellent speed of 972km/h (604mph) on the 1,588kg (3,500 Ib) thrust of a single Rolls- Royce Derwent engine (thus, it was faster than a Gloster Meteor on half as many Derwent engines). The first of two Yak-25 prototypes was modified to evaluate an idea proposed by the DA (Dal’nyaya Aviatsiya, long-range aviation). Called Burlaki (barge – hauler) this scheme was to arrange for a strategic bomber to tow a jet fighter on the end of a cable until it was deep in enemy airspace and likely to encounter hostile fighters. The friendly fighter pilot would then start his engine and cast off, ready for combat. The first of the two Yak-25 prototypes was accordingly fitted with a long tube projecting ahead of the nose, with a special connector on the end. The two aircraft would take off independently. The bomber would unreel a cable with a special connector on the end, into which the fighter would thrust its probe, as in probe/drogue flight refuelling. It would thus have a free ride to the target area. The idea was eventually rejected: towing the fighter reduced the range of the bomber, the fighter might not have enough range to get home (unless by chance it could find a friendly bomber and hook on), the long tube affected the fighter’s agility and, worst of all, the fighter pilot would have to engage the enemy after several hours sitting in a freezing cockpit with no pressurization.

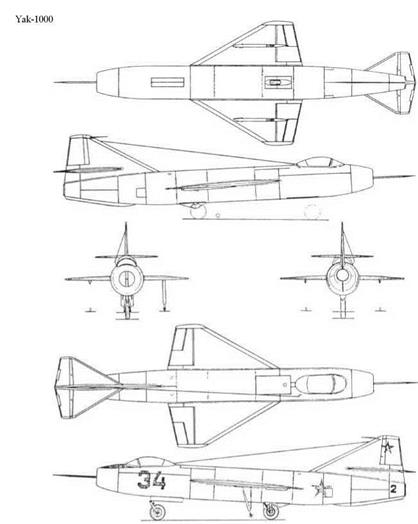

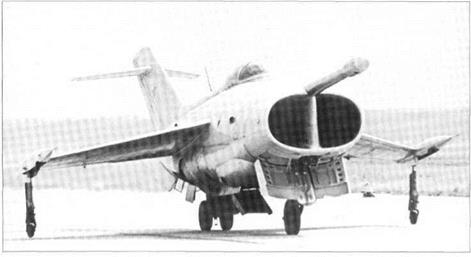

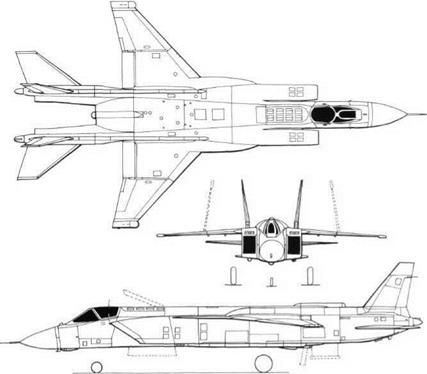

One of the least-known Soviet aircraft was the Yak-1000. The late Jean Alexander was the only Western writer to suggest that this extraordinary creation might have been intended purely for research, and even she repeated the universal belief that its engine was a Lyul’ka AL-5. In fact, instead ofthat impressive axial engine of5,000kg (11,023 Ib) thrust, the strangely numbered Yak-1000 had a Rolls- Royce Derwent of less than one-third as muchthrust. Designed in 1948-49, this aircraft was notable for having a wing and horizontal

Centre: Yak-1000.

Bottom: Yak-25E Burlaki.

tail of startlingly short span (wing span was a mere 4.52m, 14ft l0in), almost of delta form and with a thickness/chord ratio nowhere greater than 4.5 per cent and only 3.4 per cent at the wing root. Behind the rear spar the entire wing comprised a powerful slotted flap, the outer portion ofwhich incorporated a rectangular aileron. The tailplane was fixed halfway up the fin, which again was a low – aspect-ratio delta fitted with a small rudder at the top. The long tube-like fuselage had the air inlet in the nose, the air duct being immediately bifurcated to pass either side of the cockpit, which was pressurized and had an ejection-seat. The inevitably limited supply of 597 litres (131 Imperial gallons) of fuel was housed in one tank ahead of the engine and another round the jetpipe. The only way to arrange the landing gear was to have a nose – wheel and single (not twin, as commonly thought) mainwheel on the centreline and small stabilizing wheels under the wings. Flight controls were manual, the flaps, landing gear and other services were worked pneumatically, and the structure was light alloy except for the central wing spar which was high-tensile SOKhGSNA steel. Only one flight article was built, the objective being a speed in level flight of 1,750km/h (1,087mph, Mach 1.65). Taxi testing began in 1951, and as soon as high speeds were reached the Yak-1000 exhibited such dangerous instability that no attempt was made to fly it.

tail of startlingly short span (wing span was a mere 4.52m, 14ft l0in), almost of delta form and with a thickness/chord ratio nowhere greater than 4.5 per cent and only 3.4 per cent at the wing root. Behind the rear spar the entire wing comprised a powerful slotted flap, the outer portion ofwhich incorporated a rectangular aileron. The tailplane was fixed halfway up the fin, which again was a low – aspect-ratio delta fitted with a small rudder at the top. The long tube-like fuselage had the air inlet in the nose, the air duct being immediately bifurcated to pass either side of the cockpit, which was pressurized and had an ejection-seat. The inevitably limited supply of 597 litres (131 Imperial gallons) of fuel was housed in one tank ahead of the engine and another round the jetpipe. The only way to arrange the landing gear was to have a nose – wheel and single (not twin, as commonly thought) mainwheel on the centreline and small stabilizing wheels under the wings. Flight controls were manual, the flaps, landing gear and other services were worked pneumatically, and the structure was light alloy except for the central wing spar which was high-tensile SOKhGSNA steel. Only one flight article was built, the objective being a speed in level flight of 1,750km/h (1,087mph, Mach 1.65). Taxi testing began in 1951, and as soon as high speeds were reached the Yak-1000 exhibited such dangerous instability that no attempt was made to fly it.

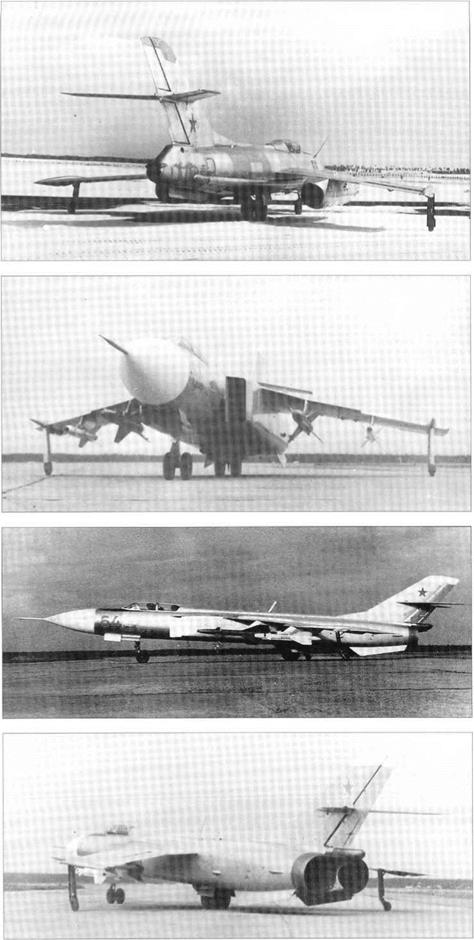

In the jet era there is no doubt that Yakovlev’s most important aircraft were the incredibly varied families of tactical twin-jets with basic designations from Yak-25 (the second time this designation was used) to Yak-28. Some of the sub-variants were experimental in nature. One was the Yak-27V, V almost certainly standing for Vysotnyi, high altitude, because it was specifically intended for high-altitude interceptions. This was a single flight article, which had originally been constructed as the Yak-121, the prototype for the Yak-27 family, with callsign Red 55. To turn it into the Yak-27V it was converted into a single-seater, and a Dushkin S-155 rocket engine was installed in the rear fuselage, replacing the braking parachute. The S-155 had a complicated propellant supply and control system, because it combined petrol (gasoline) fuel with a mixture of RFNA (red fuming nitric acid) and HTP (high-test hydrogen peroxide) oxidant, plus a nitrogen purging system to avoid explosions. Brochure thrust of the S-155 was 1,300kg (2,866 Ib) at sea level, rising to 1,550kg (3,417 Ib) at 12km (39,370ft). Airframe modifications included adding an extended and drooped outer leading edge to the wing (though the chordwise extension

was not as large as in the later Yak-28 family), converting the horizontal tail into one-piece stabiliators, fitting the rearranged tankage, and replacing the nose radar by a metal nose. The two NR-30 cannon were retained. The RD-9AK engines were replaced by the specially developed RD-9AKE, with a combustion chamber and fuel system specially tailored for high altitudes; thrust was unchanged at 2,800kg (6,173 lb). Yakovlev hired VGMukhin to join the OKB’s large test-pilot team because he had tested the mixed-power Mikoy – an Ye-50 with a similar S-155 rocket engine. He opened the test-flying programme on 26th April 1956. Service ceiling of the Yak-27V was found to be 23.5km (77,100ft), and level speed above 14km (45,900ft) about 1,913km/h (l,189mph, Machl.8).

Yakovlev had been fortunate in having members of this prolific twin-jet family in series production at four large factories, No 99 at Ulan-Ude, No 125 at Irkutsk, No 153 at Novosibirsk and No 292 at Saratov. Unfortunately, by 1964 no new orders were being placed and the end was in sight. In that year, right at the end of the development of the family, Yakovlev tried to prolong its life by undertaking a major redesign. He sent his son Sergei to study the variable inlets and engine installation of the rival Su-15, and he also carefully studied the MiG Ye-155, the prototypes for the MiG-25. All these were faster than any Yaks, and they had engines in the fuselage. Accordingly, whilst keeping as many parts unchanged as possible, the Yak-28-64 was created, and this single flight article, callsign Red 64, began flight testing in 1966. The engines remained the R-l 1AF2-300, as used in most Yak-28s (and also, as the R-l 1F2-300, in many MiG-21s), with dry and afterburning ratings of 3,950kg (8,708 Ib) and 6,120kg (13,492 Ib) respectively. Instead ofbeing hung under the wings they were close together in the rear fuselage, fed by vertical two-dimensional inlets with variable profile and area. Drop tanks could be hung under the inlet ducts on the flanks of the broad fuselage. This wide fuselage added almost a metre to the span (from 11.64m, 38ft 2%in, to 12.5m, 41ft), and removing the engines from the wings enabled the ailerons to be extended inboard to meet the flaps. Armament comprised four guided missiles, two from the K-8 family (typically an R-8M and an R-8T) and two R-3S copies of the American Sidewinder. To Yakovlev’s enormous disappointment, the huge sum spent by the OKB in developing this aircraft was wasted. Its performance was if anything inferior to that of the Yak-28P, and handling was unsatisfactory to the point of being unacceptable.

Top: Yak-36 c/n 38, with rocket pods.

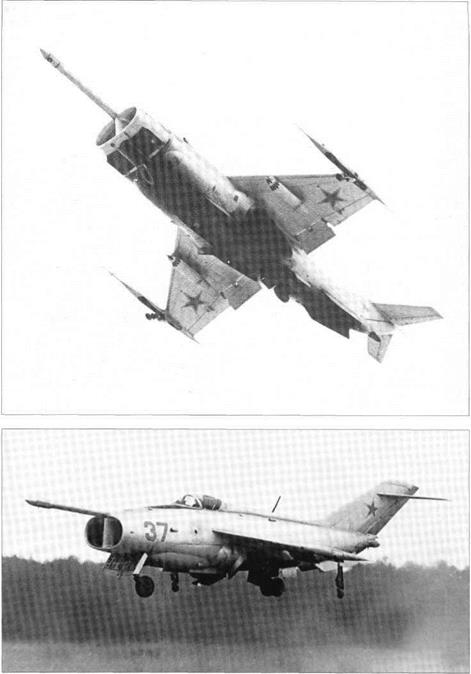

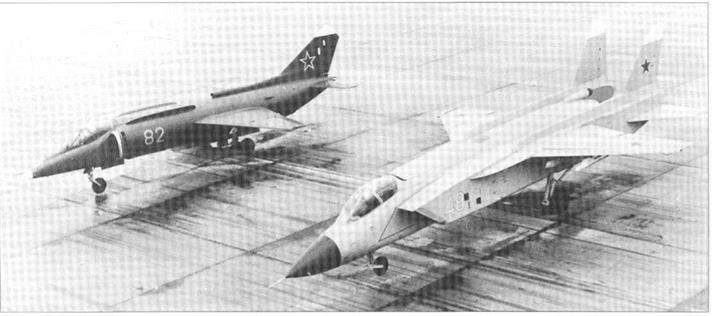

Two views of Yak-36 experimental VTOL aircraft.

Two views of Yak-36 experimental VTOL aircraft.

In 1960 Yakovlev watched the Short SC. l cavorting at Farnborough and became captivated by the concept of SWP (Russian for VTOL, vertical take-off and landing). Though he received funding for various impressive Yak-33 studies in which batteries of lift jets would have been installed in a supersonic attack aircraft, he quickly decided to build a simple test-bed in the class of the Hawker P.1127, with vectored nozzles. No turbofan existed which could readily be fitted with four nozzles, as in the British aircraft, but, after funding was provided by the MAP and the propulsion institute CIAM, K Khachaturov in the Tumanskii engine bureau developed the R-27 fighter turbojet into the R-27V-300 with a nozzle able to be vectored through a total angle of 100°. Rated initially at 6,350kg (14,0001b), this engine had a diameter of 1,060mm (3ft 5%in) and so it was a practical proposition to fit two close side-by-side in a small fuselage. Of course, the engines had to be handed, because the rotating final nozzle had to be on the outboard side. This was the basis for the Yak-36 research aircraft, intended to explore what could be done to perfect the handling of a jet-lift aeroplane able to hover. To minimise weight, the rest of the aircraft was kept as small as possible. The engines were installed in the bottom of the fuselage with nozzles at the centre of gravity, fed directly by nose inlets. The single-seat cockpit, with side-hinged canopy and later fitted with a seat which was arranged to eject automatically in any life-threatening situation, was directly above the engines. The small wing, tapered on the leading edge and with -5° anhedral, was fitted with slotted flaps and powered ailerons. Behind the engines the fuselage quickly tapered to a tailcone, and carried a vertical tail swept sharply back to place the swept horizontal tail, mounted

near the top, as far back as possible. The tailplane was fixed, and the elevators and rudder were fully powered. For control at low airspeeds air bled from the engines was blasted through downward-pointing reaction-control nozzles on the wingtips and under the tailcone and on the tip of a long tubular boom projecting ahead of the nose. The nose and tail jets had twin inclined nozzles which were controllable individually to give authority in yaw as well as in pitch. The landing gear was a simple four-point arrangement, with wingtip stabilizing wheels, of the kind seen on many earlier Yak aircraft. The OKB factory built a static-test airframe and three flight articles, Numbered 36, 37 and 38. Tunnel testing at C AHI (TsAGI) began in autumn 1962, LII pilot Yu A Garnayev made the first outdoor tethered flight on 9th January 1963 and Valentin Mukhin began free hovering on 27th September 1964. On 7th February 1966 No 38 took off vertically, accelerated to wingborne flight and then made a fast landing with nozzles at 0°. On 24th March 1966 a complete transition was accomplished, with a VTO followed by a high-speed pass followed by a VL. The LII stated that maximum speed was about l,000km/h, while the OKB claimed U00km/h (683mph). Both Nos 37 and 38 were flown to Domodedovo for Aviation Day on 9th July 1967. Later brief trials were flown from the helicopter cruiser Moskva.

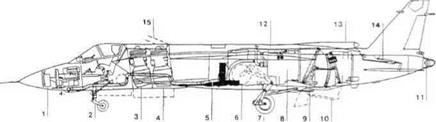

From the Yak-3 6 were derived the Yak-36M, Yak-38, Yak-38U and Yak-38M, all of which saw service with the A-VMF (Soviet naval aviation). This inspired the OKB to produce the obvious next-generation aircraft, with fully supersonic performance. A design contract was received in 1975. Yak called the project Izdeliye (Product) 48, and it received the Service designation Yak-41. Seldom had there been so many possible aircraft configura-

|

tions, but at least this time funds were made available for the necessary main engine. With much help from CIAM, this was created as the R-79V-300 by the Soyuz bureau, led after Tu – manskii’s death in 1973 by Oleg N Favorskii, and from 1987 by Vasili K Kobchenko. The R-79 was a two-shaft turbofan with a bypass ratio of 1.0, with a neat augmentor and a fully variable final nozzle joined by three wedge rings which, when rotated, could vector the nozzle through 63° for STO (short take-off) or through 95° for VTO (vertical take-off). Ratings were 11,000kg (24,250 Ib) dry, 15,500kg (34,171 Ib) with maximum augmentation and 14,000kg (30,864 Ib) with maximum augmentation combined with maximum airbleed for aircraft control. The reason the nozzle vectored through 95° was because, immediately behind the cockpit, the Yak-41 had two Rybinsk (Novikov) RD-41 lift jets in tandem whose mean inclination was 85°. Their nozzles had limited vectoring but, at this mean position, in hovering flight they blasted down and back so the main engine had to balance the longitudinal component by blasting down and forwards. Sea-level thrust of each RD-41 was 4,100kg (9,040Ib); thus, total jet lift was about22,200kg (48,942 Ib), but in fact the Yak – 41 was not designed to fly at anything like this weight. Compared with its predecessors it was far more sharp-edged and angular. The wing had a thickness/chord ratio of 4.0 per cent, and leading-edge taper of 40°. The outer wings, which in fact had slight sweepback on the trailing edge, folded for stowage on aircraft carriers. The leading edge had a large curved root extension, outboard of which was a powerful droop flap. On the trailing edge were plain flaps and powered ailerons. The wing had -4° anhedral, and was mounted on top of a wide box-like mid-fuselage, from which projected a slim nose and cock-

pit ahead of the large variable wedge inlets which led to ducts which, behind the lift engines, curved together to feed the main engine. The latter’s nozzle was as far forward as possible. Beside it on each side was a narrow but deep beam carrying a powered tailplane and a slightly outward-sloping fin with a small rudder. Unlike most military Yak jets the Yak-41 had a conventional tricycle landing gear. In hovering flight recirculation was minimised by the open lift-bay doors, a hinged transverse dam across the fuselage ahead of the main gears, a large almost square door hydraulically forced down ahead of the main engine nozzle, and a long horizontal strake along the sharp bottom edge of the fuselage on each side. Fuselage tanks held 5,500 litres (1,210 Imperial gallons) of fuel, and a 2,000 litre (440 Imperial gallon) conformal tank could be scabbed under the fuselage. Flight and engine controls were eventually interlinked and digital, the hovering controls comprising twin tandem jets at the wingtips and a laterally swivelling nozzle under the nose (which replaced yaw valves at the tip of each tailcone). An interlinked system provided automatic firing of the K-36LV seat in any dangerous flight situation. In 1985 it was recognized that such a complex and costly aircraft ought to have multi-role capability, and the new designation Yak-41 M was issued for an aircraft with extremely comprehensive avionics and weapons. Equipment included a 30mm gun and up to 2.6 tonnes (5,732 Ib) of ordnance on four underwing pylons. The OKB received funding for a static/fatigue test aircraft called 48-0, a powerplant test-bed (48-1) and two flight articles, 48-2 (callsign 75) and 48-3 (callsign 77). Andrei A Sinitsyn flew ’75’ as a conventional aircraft at Zhu – kovskii on 9th March 1987. He first hovered ’77’ on 29th December 1989, and in this aircraft he made the first complete transition on 13th June 1990. Maximum speed was 1,850km/h (1,150mph, Mach 1.74) and rate of climb 15km (49,213ft) per minute. In April 1991 Sinitsyn set 12 FAI class records for rapid climb with various loads, and as the true designation was classified the FAI were told the aircraft was the ‘Yak-141’. In September 1992 48-2 was flown to the Farnborough airshow, its side number 75 being replaced by ‘141’. A year earlier the CIS Navy had terminated the whole Yak-41 M programme, and the appearance in the West was a fruitless last attempt to find a partner to continue the world’s only programme at that time for a supersonic jet – lift aircraft. Apart from publicity, all today’s Yakovlev Corporation finally received for all this work was a limited contract to assist Lockheed Martin’s Joint Strike Fighter.

Opposite: Yak-41 M with Yak-38M.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This page, top: Yak-141, No 75 on carrier.

This page, top: Yak-141, No 75 on carrier.