Sukhoi Su-37

Purpose: To create the optimised multirole fighter derived from the Su-27.

Design Bureau: AOOT ‘OKB Sukhoi’, Moscow.

The superb basic design of the T-10 led not only to the production Su-27 but also to several derivative aircraft. Some, such as the Su-34, are almost completely redesigned for new missions. One of the main objectives has been to create even better multirole fighters, and via the Su-27UB-PS and LMK 24-05 Sukhoi and the Engine KB ‘Lyul’ka-Saturn’ have, in partnership with national laboratories and the avionics industry, created the Su-37. The prototype was the T10M-11, tail number 711, first flown on 2nd April 1996. The engine nozzles were fixed on the first flight, but by September 1996, when it arrived at the Farnborough airshow, this aircraft had made 50 flights with nozzles able to vector. At the British airshow it astounded observers by going beyond the dramatic Kobra manoeuvre and making a complete tight 360° somersault essentially within the aircraft’s own length and without change in altitude. Called Kulbit (somersault), this manoeuvre has yet to be emulated by any other aircraft. In 1999 low-rate production was being planned at Komsomolsk.

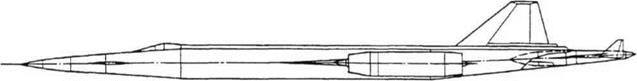

Essentially the Su-37 is an Su-35 with vectoring engines. Compared with the Su-27 the Su-35 has many airframe modifications including canards, taller square-top fins (which are integral tanks) and larger rudders, double-slotted flaps, a bulged nose housing the electronically scanned antenna of the N011M radar, an extended rear fuselage housing the aft-facing defence radar, twin nosewheels and, not least, quad FBW flight controls able to handle a longitudinally unstable aircraft. In addition to these upgrades the Su-37 has AL-31FP engines, each with dry and augmented thrust of 8,500 and 14,500kg (18,740 and 31,9671b) respectively. These engines have efficient circular nozzles driven by four pairs of actuators to vector ±15° in pitch. Left/right vectoring is precluded by the proximity of the enlarged rear fuselage, but engine General Designer Viktor Chepkin says ‘Differential vectoring in the vertical plane is synonymous with 3-D multi-axis nozzles’. In production engines the actuators are driven by fuel pressure.

It is difficult to imagine how any fighter with fixed-axis nozzles could hope to survive in any kind of one-on-one engagement with this aircraft.

|

Dimensions Span (over ECM containers) Length Wing area |

15.16m 22.20m 62.0m2 |

49 ft 8k! in 72 ft 10 in 667ft2 |

|

Weights |

||

|

Weight empty |

17tonnes |

37,479 Ib |

|

Maximum loaded |

34 tonnes |

74,956 Ib |

|

Performance |

||

|

Maximum speed |

||

|

at sea level |

l,400km/h |

870mph(Machl. l4) |

|

at high altitude |

2,500 km/h |

1,553 mph (Mach 2.35) |

|

Rate of climb |

230 m/s |

45,276 ft/min |

|

Service ceiling |

18,800m |

61,680ft |

|

Range (internal fuel) |

3,300 km |

2,050 miles |

Purpose: To provide data to support the design of a superior air-combat fighter. Design Bureau: AOOT ‘OKB Sukhoi’, Moscow.

Almost unknown until its first flight, this aircraft is one of the most remarkable in the sky. Any impartial observer cannot fail to see that, unless Sukhoi’s brilliance has suddenly become dimmed, it is a creation of enormous importance. Like the rival from MiG, it provides the basis for a true ‘fifth-generation’ fighter which with rapid funding could swiftly become one of the greatest multirole fighters in the world. Unfortunately, in the Russia of today it will do well to survive at all, especially as the WS has for political and personality reasons shown hostile indifference. In fact on 1st February 1996, when the first image of a totally new Sukhoi fighter leaked out in the form of a fuzzy picture of a tabletop model, the WS Military Council instantly proclaimed that this aircraft ‘is not prospective from the point of view of re-equipment within 201025’. In fact the first hint of this project came during a 1991 visit by French journalists to CAHI (TsAGI), when they were shown a

model of an aircraft with FSW (forward – swept wings) and canard foreplanes called the Sukhoi S-32. At the risk of causing confusion, Sukhoi uses S for projects and Su for products, the same number often appearing in both categories but for totally different aircraft (for example, the Su-32 is piston-engined). In December 1993, during the Institute’s 75th-birthday celebrations, its work on the FSW was said to be ‘for a new fighter of Sukhoi design’. The model shown in February 1996 again bore the number ’32’ but clearly had tailplanes as well as canards. It had been known for many years that the FSW has important aeroelastic advantages over the traditional backswept wing (see OKB-1 bombers and Tsybin LL). At least up to Mach 1.3 (1,400 tol,500km/h, 870 to 930mph) the FSW offers lower drag and superior manoeuvrability, and the lower drag also translates as longer range. A further advantage is that takeoffs and landings are shorter. The fundamental aeroelastic problem with the FSW can be demonstrated by holding a cardboard wing out of the window of a speeding vehicle. A cardboard FSW tends to bend upwards violently, out ofcontrol. An FSW for a fastjet was

|

thus very difficult to make until the technology of composite structures enabled the wing to be designed with skins formed from multiple layers of adhesive-bonded fibres of carbon or glass. With such skins the directions of the fibres can be arranged to give maximum strength, rather like the directions of the grain in plywood. The first successful jet FSW was the Grumman X-29, first flown in December 1984. This exerted a strong influence on the Sukhoi S-32 design team, which under Mikhail Simonov was led by First Deputy General Designer Mikhail A Pogosyan, and included Sergei Korotkov who is today’s S-37 chief designer. From 1983 the FSW was exhaustively investigated, not only by aircraft OKBs but especially by CAHI (TsAGI) and the Novosibirsk-based SibNIA, which tunnel-tested several FSW models based loosely on the Su-27. By 1990 Simonov was determined to create an FSW prototype, and three years later the decision had been taken not to wait for non-existent State funds but instead to put every available Sukhoi ruble into constructing such an aircraft. Despite a continuing absence ofofficial funding, this has proved to be possible because of income from export

sales of fighters ofthe Su-27 family. Construction began in early 1996, but in that year Western aviation magazines began chanting that the S-32 was soon to fly. Uncertain about the outcome, Simonov changed the designation to S-37, so that he could proclaim The S-32 does not exist’. It had been hoped to fly the radical new research aircraft at the MAKS – 97 airshow, but it was not ready in time. It was a near miss, because the almost completed S-37 had begun ground testing in July, and by August it was making taxi tests at LII Zhukovskii, the venue for the airshow. After MAKS 97 was over it emerged again, and on 25th September 1997 it began its flight test programme. The assigned pilot is Igor Viktorovich Votintsev. A cameraman at the LII took film which was broadcast on Russian TV, when the aircraft was publicised as the Berkut (golden eagle). On its first flight, when for a while the landing gear was retracted, the S-37 was accompanied by a chase Su-30 carrying a photographer. It is a long way from being an operational fighter, but that is no rea

son for dismissing it as the WS, Ministry of Defence and the rival MiG company have done. Fortunately there are a few objective people in positions of authority, one being Marshal Yevgenii Shaposhnikov, former WS C-in-C. Despite rival factions both within the WS and industry (and even within OKB Sukhoi) this very important aircraft has made it to to the flight-test stage. Whether it can be made to lead to a fully operational fighter is problematical.

The primary design objective ofthis aircraft is to investigate the aerodynamics and control systems needed to manoeuvre at angles of attack up to at least 100°. From the outset it was designed to be powered by two AL-41F augmented turbofans from Viktor Chepkin’s Lyul’ka Saturn design bureau. In 1993 he confidentially briefed co-author Gunston on this outstanding engine. At that time it had already begun flight testing under a Tu-16 and on one side of a M1G-25PD (aircraft 84-20). Despite this considerable maturity it was not cleared as the sole source of propulsion in time for the S-37, though the aircraft could be re-engined later. Accordingly the Sukhoi prototype is at

|

present powered by two AL-31F engines, with dry and afterburning thrusts of 8,100 and 12,500kg (17,557 and 27,560 Ib), respectively. Special engines were tailored to suit the S-37 installation, but at the start of the flight programme they still lacked vectoring nozzles. The engines are mounted only a short distance apart, fed by ducts from lateral inlets of the quarter-circle type. At present the inlets are of fixed geometry, with inner splitter plates standing away from the wall of the fuselage and bounded above by the underside ofthe very large LERX (leading-edge root extension), which in fact is quite distinct from the root of the wing. The wing itself comprises an inboard centroplan with leading-edge sweep of 70°, leading via a curved corner to the main panel with forward sweep of 24° on the leading edge and nearly 40° on the trailing edge. The forward-swept portion has a two – section droop flap over almost the whole leading edge, and plain trailing-edge flaps and outboard ailerons. Structurally it is described as ’90 per cent composites’. The main wing panels are designed so that in a derived aircraft they could fold to enable the aircraft

|

to fit into the standard Russian hardened aircraft shelter. Aerodynamically the S-37 is another ‘triplane’, having canard foreplanes as well as powered tailplanes. The former are greater in chord than those of later Su-27 derivatives, the trailing edge being tapered instead of swept back. Likewise the tailplanes have enormous chord, but as the leading – edge angle is over 75° their span is very short. As in other Sukhoi fighters, the tailplanes are pivoted to beams extending back from the wing on the outer side of the engines. Unlike previous Sukhois the tailplanes are not mounted on spigots on the sides of the beams but on transverse hinges across their aft end. These beams also carry the fins and rudders, which are similar to those of other Sukhois apart from being further apart (a long way outboard of the engines) and canted outward. After flight testing had started the rudders were given extra strips (in Russia called knives) along the trailing edge. When the S-37 is parked, with hydraulic pressure decayed, the foreplanes, tailplanes and ailerons come to rest 30° nose-up. The landing gear is almost identical to that ofthe Su-27K, with twin steerable nosewheels. In the photographs released so far no airbrakes or centreline braking-parachute container can be seen. In

ternal fuel capacity is a mere 4,000kg (8,8181b), though much more could be accommodated. The cockpit has an Su-27 type upward-hinged canopy, and a sidestick on the right. The airframe makes structural provision for 8 tonnes (17,637 Ib) of external and internal weapons, including a gun in the left centroplan. It is also covered in numerous flush avionics antennas, though the only ones that are functional are those necessary for aerodynamic and control research. A bump to starboard ahead of the wraparound windscreen could later contain an opto-electronic (TV, IR, laser) sight, while the two tail beams are continued different distances to the rear to terminate in prominent white domes, doubtless for avionics though they could conceivably house braking parachutes. These domes stand out against the startling dark blue with which this aircraft has been painted. Sukhoi has stressed that this aircraft incorporates radar-absorbent and beneficially reflective ‘stealth’ features, though again the objective is research. Also standing out visually are the white-bordered red stars, though of course the aircraft is company-owned and bears ‘OKB Sukhoi’ in large yellow characters on the fuselage, along with callsign 01, which confusingly is the same as the MiG 1.44.

The Russians have traditionally had a strong aversion to what appear to be unconventional solutions, and this has in the past led to the rejection of many potentially outstanding aircraft. The S-37 has to overcome this attitude, as well as the bitter political struggle within the OKB, with RSK MiG, with factions in the Ministry of Defence and air force and, not least, two banks which are battling to control the OKB.

Dimensions

Span 16.7m 54 ft m in

Length (ex PVO boom) 22.6m 74 ft 1% in

Wing area about 67m2 721 ft2

Weights

Take-off mass given as 24 tonnes 52,910 Ib

(the design maximum is higher)

Performance

Design maximum speed 1,700 km/h, 1,057 mph (Mach 1.6)

(which would explain the fixed-geometry inlets. At Mach numbers much higher than this the FSW is less attractive)

At press time no other data had emerged.

Purpose: To study wings for transonic flight. Design Bureau: OKB-256, ChiefDesigner Pavel Vladimirovich T sybin, professor at Zhukovskii academy.

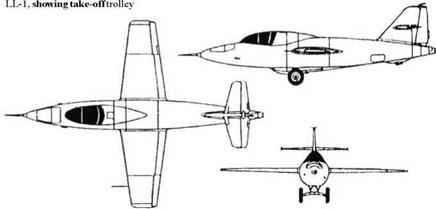

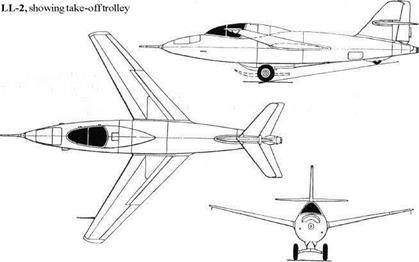

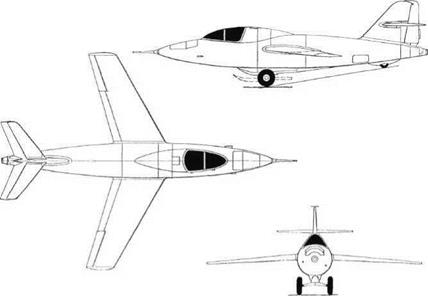

In September 1945 the LIl-MAP (Flight Research Institute) asked Tsybin to investigate wings suitable for flight at high Mach numbers (if possible, up to 1). In 1946 numerous models were tested at CAHI (TsAGI), as a result of which OKB-256 constructed the Ts-1, also called LL-1 (flying laboratory 1). Almost in parallel, a design team at the OKB led by A V Beresnev developed a new fuselage and tail and two new wings, one swept back and the other swept forward. The LL-1 made 30 flights beginning in mid-1947 with NIl-WS pilot M Ivanov, and continuing with Amet- Khan Sultan, S N Anokhin and N S Rybko. On each flight the aircraft was towed by a Tu-2. Casting off at 5-7km (16,400-23,000ft), the aircraft was dived at 45°-60° until at full speed it was levelled out and the rocket fired. In winter 1947-48 the second Ts-1 was fitted with the swept-forward wing to become the LL-3. This made over 100 flights, during which a speed of l,200km/h (746mph) and Mach 0.97 were reached, without aeroelastic problems and yielding much information. The swept – back wing was retrofitted to the first aircraft to create the LL-2, but this was never flown.

![]()

The original Ts-1 (LL-1) was essentially allwood. The original wing had two Delta (resin – bonded ply) spars, a symmetric section of 5 per cent thickness, 0° dihedral and +2° incidence. It had conventional ailerons and plain flaps (presumably worked by bottled gas pressure). Take-offs were made from a two – wheel jettisonable dolly, plus a small tail – wheel. In the rear fuselage was a PRD-1500 solid-propellant rocket developed by 11 Kar – tukov, giving 1,500kg (3,307 Ib) (more at high altitude) for eight to ten seconds. Flight controls were manual, with mass balances. On early flights no less than one tonne (2,2051b) of water was carried as ballast, simulating instrumentation to be installed later. This was jettisoned before landing, when the aircraft (now a glider) was much more manoeuvrable. Landings were made on a skid. Various kinds of instrumentation were carried, and at times at least one wing was tufted and photographed. The LL-3 was fitted with a metal wing with a forward sweep of 30° (according to drawings this was measured on the leading edge), with no less than 12° dihedral. The new tailplane had a leading-edge sweepback of 40°. To adjust the changed centres of lift and of gravity new water tanks were fitted in the nose and tail. Both LL-1 and LL-3 were considered excellent value for money.

The original Ts-1 (LL-1) was essentially allwood. The original wing had two Delta (resin – bonded ply) spars, a symmetric section of 5 per cent thickness, 0° dihedral and +2° incidence. It had conventional ailerons and plain flaps (presumably worked by bottled gas pressure). Take-offs were made from a two – wheel jettisonable dolly, plus a small tail – wheel. In the rear fuselage was a PRD-1500 solid-propellant rocket developed by 11 Kar – tukov, giving 1,500kg (3,307 Ib) (more at high altitude) for eight to ten seconds. Flight controls were manual, with mass balances. On early flights no less than one tonne (2,2051b) of water was carried as ballast, simulating instrumentation to be installed later. This was jettisoned before landing, when the aircraft (now a glider) was much more manoeuvrable. Landings were made on a skid. Various kinds of instrumentation were carried, and at times at least one wing was tufted and photographed. The LL-3 was fitted with a metal wing with a forward sweep of 30° (according to drawings this was measured on the leading edge), with no less than 12° dihedral. The new tailplane had a leading-edge sweepback of 40°. To adjust the changed centres of lift and of gravity new water tanks were fitted in the nose and tail. Both LL-1 and LL-3 were considered excellent value for money.

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Purpose: To create a winged strategic delivery vehicle.

Design Bureau: OKB-256, Podberez’ye, Director P V Tsybin.

In the early 1950s it was evident that the forthcoming thermonuclear weapons would need strategic delivery systems of a new kind. Until the ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) was perfected the only answer appeared to be a supersonic bomber. After much planning , Tsybin went to the Kremlin on 4 th March 1954 and outlined his proposal for a Reak – tivnyi Samolyot (jet aeroplane). The detailed and costed Preliminary Project was issued on 31st January 1956, with a supplementary submission of a reconnaissance version called 2RS. Korolyov’s rapid progress with the R-7 ICBM (launched 15th May 1957 and flown to its design range on 21st August 1957) caused the RS to be abandoned. All effort was transferred to the 2RS reconnaissance aircraft (described next).

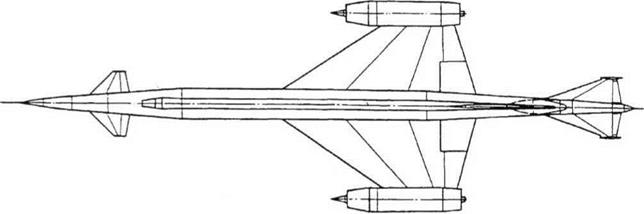

The RS had an aerodynamically brilliant configuration, precisely repeated in the British Avro 730 which was timed over a year later. The wing was placed well back on the long circular-section fuselage and had a symmetric section with a thickness/chord ratio of 2.5 to 3.5 per cent. It had extremely low aspect ratio (0.94) and was sharply tapered on both edges. Large-chord flaps were provided inboard of conventional ailerons, other flight

controls comprising canard foreplanes and a rudder, all surfaces being fully powered. The cockpit housed a pilot in a pressure suit, seated in an ejection-seat under a canopy linked to the tail by a spine housing pipes and controls. The RS was to be carried to a height of 9km (29,528ft) under a Tu-95N. After release it was to accelerate to supersonic speed (design figure 3,000km/h) on the thrust oftwo jettisoned rocket motors. The pilot was then to start the two propulsion engines, mounted on the wingtips. These were RD-013 ramjets, designed by Bondaryuk’s team at OKB-670. Each had a fixed-geometry multi-shock inlet and convergent/divergent nozzle matched to the cruise Mach number of 2.8. Internal diameter and length were respectively 650mm (2ft IHin) and 5.5m (18ft 1/2in). The 1955 project had 16.5 tonnes offuel, or nearly 3.5 times the 4.8-t empty weight, but by 1956 the latter had grown and fuel weight had in consequence been reduced. The military load was to be a 244N thermonuclear bomb weighing 1,100kg (2,4251b). The only surviving drawing shows this carried by a tailless-delta missile towed to the target area attached behind the RS fuselage (see below). Data for this vehicle are not known.

Outstandingly advanced for its day, had this vehicle been carried through resolutely it would have presented ‘The West’ with a serious defence problem.

|

Dimensions

|

|