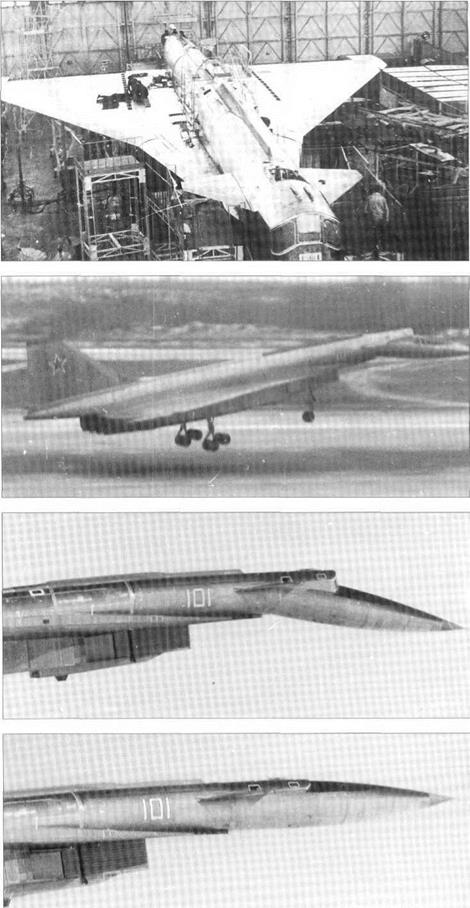

Sukhoi T-4, 100

Purpose: To create a Mach-3 strategic weapons system.

Design Bureau: P O Sukhoi, Moscow, with major subcontract to TMZ, Tushino Machine-Building Factory.

This enormous project was triggered in December 1962 by the need to intercept the B-70 (or RS-70), ‘A-ll’ (A-12, later SR-71), Hound Dog and Blue Steel. At an early stage the mission was changed to strategic reconnaissance and strike for use against major surface targets. It was also suggested that the basic air vehicle could form the starting point for the design of an advanced SST. From the outset there were bitter arguments. Initially these centred on whether the requirement should be met by a Mach-2 aluminium aircraft or whether the design speed should be Mach 3, requiring steel and/or titanium. In January

1963 Mach 3 was selected, together with a design range at high altitude on internal fuel of 6,000km (3,728 miles). General Constructors Sukhoi, Tupolev and Yakovlev competed, with the T-4, Tu-135 and Yak-33 respectively. The Yak was too small (in the TSR.2 class) and did not meet the requirements, and though it looked like the B-70 the Tupolev was an aluminium aircraft designed for Mach 2.35. From the start Sukhoi had gone for Mach 3, and its uncompromising design resulted in its being chosen in April 1963. This was despite the implacable opposition not only of Tupolev but also of Sukhoi’s own deputy Yevgenii Ivanov and many of the OKB’s department heads, who all thought this demanding project an unwarranted departure from tactical fighters. Over the next 18 months their opposition thwarted a plan for the former Lavochkin OKB and factory to assist the

T-4, and in its place the Boorevestnik (stormy petrel) OKB and the TMZ factory were appointed as Sukhoi branch offices, the Tushino plant handling all prototype construction. A special WS commission studied the project from 23rd May to 3rd June 1963, and a further commission studied the refined design in February-May 1964. By this time the T-4 was the biggest tunnel-test project at CAHI (TsAGI) and by far the largest at the Central Institute of Aviation Motors. The design was studied by GKAT (State aircraft technical committee) from June 1964, and approved by it in October of that year. By this time it had outgrown its four Tumanskii R-15BF-300 or Zubets RD-17-15 engines and was based on four Kolesov RD-36-41 engines. In January 1965 it was decided to instal these all close together as in the B-70, instead of in two pairs. Mockup review took place from 17th January

to 2nd February 1966, with various detachable weapons and avionics pods being offered. Preliminary design was completed in June 1966, and because its take-off weight was expected to be 100 tonnes the Factory designation 100 was chosen, with nickname Sotka (one hundred). The first flight article was designated 101, and the static-test specimen 100S. The planned programme then included the 102 (with a modified structure with more composites and no brittle alloys) for testing the nav/attack system, the 103 and 104 for live bomb and missile tests and determination of the range, the 105 for avionics integration and the 106 for clearance of the whole strike/reconnaissance system. On 30th December 1971 the first article, Black 101, was transferred from Tushino to the LII Zhukovskii test airfield. On 20th April 1972 it was accepted by the flight-test crew, Vladimir Ilyushin and navigator Nikolai Alfyorov, and made its first flight on 22nd August 1972. The gear was left extended on Flights 1 through 5, after which speed was gradually built up to Mach 1.28 on Flight 9 on 8th August 1973. There were no serious problems, though the aft fuselage tank needed a steel heat shield and there were minor difficulties with the hydraulics. The WS request for 1970-75 included 250 T-4 bombers, for which tooling was being put in place at the world’s largest aircraft factory, at Kazan. After much further argument, duringwhich Minister P V Demen – t’yev told Marshal Grechko he could have his enormous MiG-23 order only if the T-4 was abandoned, the programme was cancelled. Black 101 flew once more, on 22nd January 1974, to log a total of lOhrs 20min. Most of the second aircraft, article 102, which had been about to fly, went to the Moscow Aviation Institute, and Nos 103-106 were scrapped. Back in 1967 the Sukhoi OKB had begun working on a totally redesigned and significantly more advanced successor, the T-4MS, or 200. Termination ofthe T-4 resulted in this even more remarkable project also being abandoned. In 1982 Aircraft 101 went to the Monino museum. The Kazan plant instead produced the Tu-22MandTu-160.

In all essentials the T-4 was a clone on a smaller scale of the North American B-70. The structure was made of high-strength titanium alloys VT-20, VT-21L and VT-22, stainless steels VIS-2 and VIS-5, structural steel VKS-210 and, for fuel and hydraulic piping, soldered VNS-2 steel. The wing, with 0° an – hedral, had an inboard leading-edge angle of 75° 44′, changed over most of the span to 60° 17′. Thickness/chord ratio was a remark-

able 2.7 per cent. The leading edge was fixed. The flight controls were driven by irreversible power units in a quadruplex FBW (fly-bywire) system with full authority but automatic manual reversion following failure of any two channels. They comprised four elevens on each wing, flapped canard foreplanes and a two-part rudder. The fuselage had a circular diameter of 2.0m (6ft 6%in). At airspeeds below 700km/h (435mph) the nose could be drooped 12° 12′ by a screwjack driven by hydraulic motors to give the pilot a view ahead. Behind the pilot (Ilyushin succeeded in getting the proposed control wheel replaced by a stick) was the navigator and systems manager. Both crew had a K-36 ejection-seat, fired up through the normal entrance hatch, and aircraft 101 also had a pilot periscope. Behind the pressure cabin was a large refrigerated fuselage section devoted to electronics. Next came the three fuel tanks, filled with 57 tonnes (125,661 Ib) of specially developed RG-1 naphthyl fuel similar to JP-7. Each tank had a hydraulically driven turbopump, and the fuel system was largely automated. A production T-4 would have had provision for a large drop tank under each wing, and for air refuelling. Behind the aft tank were systems compartments, ending with a rectangular tube housing quadruple cruciform braking parachutes. Under the wing was the enor

mous box housing the air-inlet systems and the four single-shaft RD-36-41 turbojets, each with an afterburning rating of 16,000kg (35,273 Ib). An automatic FBW system governed the engines and their three-section variable nozzles and variable-geometry inlets. Each main landing gear had four twin- tyred wheels and retracted forwards, rotating 90° to lie on its side outboard of the engine duct. The nose gear had levered suspension to two similar tyres, with wheel brakes, and used the hydraulic steering as a shimmy damper. It retracted backwards into a bay between the engine ducts. The four autonomous hydraulic systems were filled with KhS-1 (similar to Oronite 70) and operated at the exceptional pressure of 280kg/cm2 (3,980 lb/in2). A liquid oxygen system was provided, together with high-capacity environmental systems which rejected heat to both air and fuel. The crew wore pressure suits. The main electrical system was generated as 400-Hz three-phase at 220/115 V by four oil – cooled alternators rated at 60 kVA. Aircraft 101 never received its full astro-inertial navigation system, nor its planned ‘complex’ of electronic-warfare, reconnaissance and weapon systems. The latter would have included two Kh-45 cruise missiles, developed by the Sukhoi OKB, with a range of 1,500km (932 miles).

![]()

|

Like the B-70 this was a gigantic programme which broke much new ground (the OKB said ‘200 inventions, or600 ifyou include manufacturing processes’) yet which was finally judged to have been not worth the cost.

|

Dimensions Span Length Wing area |

22.00m 44.50m 295.7m2 |

72 ft 2% in 146ft 3,183ft2 |

|

Weights |

||

|

Empty (as rolled out) |

54,600kg |

120,370 Ib |

|

(equipped) |

55,600kg |

122,575 Ib |

|

Loaded (normal) |

114,400kg |

252,205 Ib |

|

(maximum) |

136tonnes |

299,824 Ib |

|

Design Performance |

||

|

Max and cruising speed |

3,200 km/h |

1,988 mph (Mach 3.01) |

|

at sea level |

l,150km/h |

715 mph (Mach 0.94) |

|

Service ceiling |

24km |

78,740 ft |

|

Range |

at 3,000 knYh |

1,864 mph (Mach 2.82) |

|

(clean) |

6,000 km |

3,728 miles |

|

(drop tanks) |

7,000km |

4,350 miles |

|

Take-off run |

||

|

(normal loaded weight) |

1,000m |

3,281 ft |

|

Landing speed/run |

260 kmh |

161.6 mph |

|

with parachutes |

950m |

3,117ft |

Purpose: To test wing forms for the 100 aircraft.

Purpose: To test wing forms for the 100 aircraft.

Design Bureau: P O Sukhoi, Moscow.

Another of the aircraft used to provide research support for the 100, or T-4, was this modified Su-9 interceptor. In the period 196670 this aircraft was fitted with a succession of different wings. Most testing was done at LII Zhukovskii.

The 100L was originally a test Su-9, with side number (callsign) Red 61 (the same as for the T6-1, and also for the first two-seat MiG-21, but this had finished testing at LII before the 100L arrived). The aircraft was fitted with telemetry with a diagonal blade antenna under the nose, but apparently not with a cine camera at the top of the fin. The various test wings were manufactured by adding to the existing Su-9 wing box, in most cases ahead of the wing box only. The first experimental wing was little changed in plan view: the wing was given an extended sharp leading edge which extended the tip to a point. Three further wings with sharp leading edges were

tested, as well as one with a ‘blunt leading edge’. This meant that it was the sharply swept inboard leading edge that was blunt, because at least one of the wings was fitted with a leading edge which in four stages increased in sweepback from tip to root to meet the fuselage at 75°. All the test wings had perforated leading edges from which smoke trails could be emitted. Further testing was done with a sharp-edged horizontal tail.

|

Results from this aircraft were aerodynamic, not structural, but they materially assisted the design ofthe 100.