Sukhoi T-3 and PT-7

Purpose: To create a supersonic radar – equipped interceptor.

Design Bureau: Reopened OKB-51 of P O Sukhoi, Moscow.

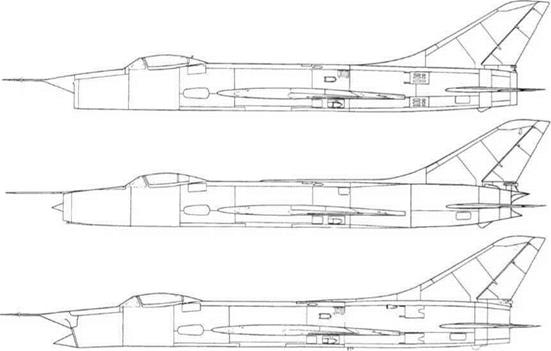

After closure of his OKB, in December 1949 Sukhoi became deputy to his old colleague A N Tupolev, where among other things he collaborated with CAHI (TsAGI) in establishing the best wing for supersonic fighters. He played the central role in deciding on two contrasting forms. For tactical fighters the choice was an S (Strelovidnoye, arrow like) swept wing with a!4-chord sweep angle of 60° or 62°, and for radar-equipped interceptors the best answer was a T (Treoogol’noye, three-angled, ie delta) wing with J4-chord sweep angle of 57° or 60°. For obvious reasons, the latter type of wing was soon dubbed Balalaika. On Stalin’s death Sukhoi applied for permission to reopen his OKB. This was at once granted, and in May 1953 he gathered his team at the original premises at 23A Po – likarpov Street. Following from his aerodynamic research he received MAP contracts for basically similar aircraft, S-l with the S wing and T-l with the T wing. As he chose to build large aircraft powered by a powerful Lyul’ka engine, which matured rapidly, their development was swift. S-l led to the production Su-7 and many other aircraft. T-l was replaced on the drawing board by T-3, and

this was flown by V N Makhalin on 26th May 1956. Just over a month later it was the final aircraft in the parade of new fighters at Tushi – no on 24th June, causing intense interest and great confusion in the West. A few weeks behind came the PT-7. These were tested intensively by a pilot team which included Pronyarkin, Koznov, Kobishkan and the future Sukhoi chief test pilot Vladimir Ilyushin, son of the General Designer.

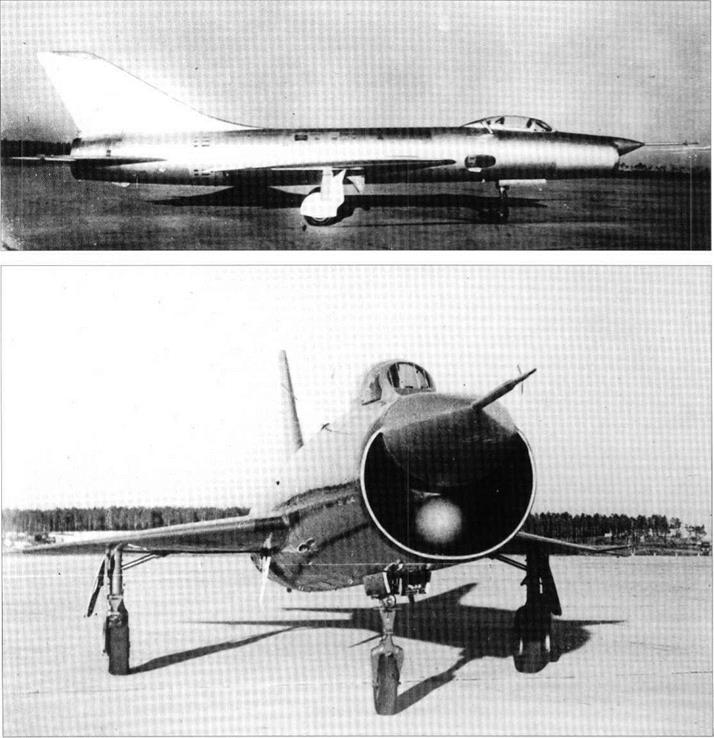

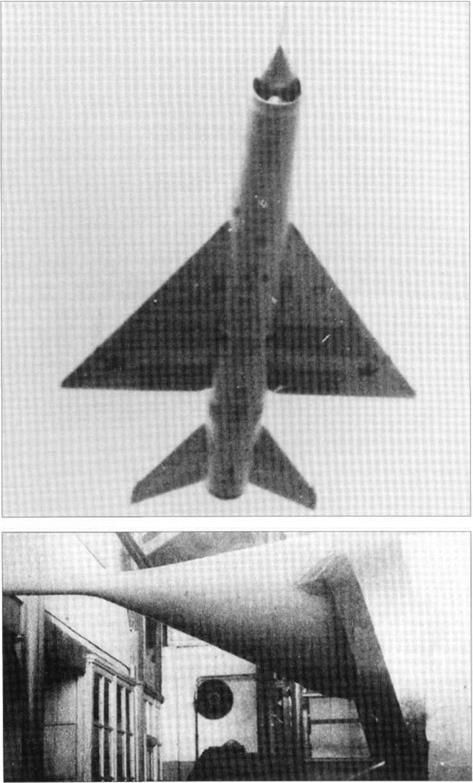

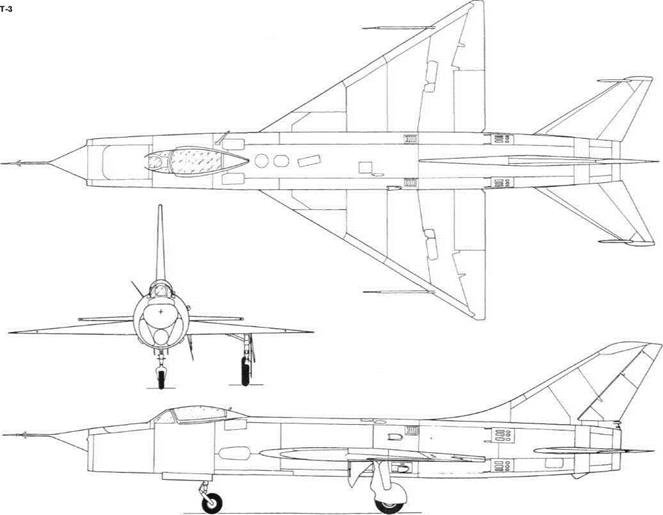

Like S-l, the T-3 had a barrel-like fuselage, much of its length being occupied by the big afterburning AL-7F engine, rated at 9,000kg (19,840 Ib) with afterburner and 6,500kg (14,330 Ib) dry. The tails of the two aircraft were almost identical, and there were only minor differences in the cockpit, landing gear and most of the systems. The wings of both aircraft were in the low/mid position, attached by precision bolts to strong forged root ribs on heavy forged fuselage frames. The wing had S-9s profile with a thickness/chord ratio of4.2 per cent over most of the span. The shape was almost a perfect delta, with a leading-edge angle of 60°. The leading edge was fixed, while the trailing edge comprised rectangular slotted flaps with a maximum angle of 25° and sharply tapered ailerons with inset hinges which extended to the near-pointed tips. Incidence was 0° and dihedral -2° (ie, 2° anhedral). Structurally the wing had three main spars, each principally a machined forg

ing, plus a rear spar to carry the trailing-edge surfaces. The leading edge was attached to the front of a further spar forming the front of the structural box. The forward triangle ahead of Spar 1 and the volume between Spars 2 and 3 were sealed and formed integral fuel tanks. The whole space between Spars 1 and 2 was occupied by the retracted main landing gear. The flaps were driven at their inboard ends by electro-hydraulic power units inside fairings under the lower wing surface. The circular-section fuselage was liberally covered with access doors and hatches. The nose was just one of several contrasting answers tested by Sukhoi to the problem of fitting radar into a supersonic fighter. The fire-control system was to be one of the Uragan (Hurricane) family, with the search scanner at the top of the nose and the Almaz (Diamond) ranging radar underneath inside the inlet. The main scanner was inside a low-drag radome in the form of a flattened cone (with a curious upward tilt) from which projected the PVD-7 instrumentation boom combining the pitot/static heads with pitch and yaw vanes. Additional instrument booms were mounted inboard of each wingtip. Even though the T-3 was to be a supersonic aircraft there seemed no alternative to making the radome over the ranging set a bluff hemisphere, which had an adverse effect on pressure recovery in the air inlet. The latter

immediately divided into left and right ducts which quickly expanded into vertically symmetric ducts along each fuselage wall. These combined behind the cockpit into a circular tube passing above the wing and then expanding to fill virtually the entire fuselage cross-section to mate with the face of the engine compressor at Frame 29. Between Frames 31 and 32 on each side of the top of

the fuselage was a large grilled aperture through which hot air could be violently expelled from the compressor during engine start. At Frame 32 a bolted joint enabled the entire rear fuselage to be removed for servicing or changing the engine. At Frame 38 were hinged four door-type airbrakes with large slot perforations. At Frame 43 were the skewed pivots for the horizontal tailplanes, each of which was a single-piece ‘slab’ with a leading-edge sweep of 60° and an anti-flutter mass projecting forwards near each tip. The large fin curved away from a dorsal extension

in which a screwed panel gave access to the power unit driving the rudder, which was hung on three inset hinges. Each tail surface had chem-milled skins attached to ribs at 90° to the surface rear spar. The fuselage tail end was mainly of titanium. The nose landing gear had a 660 x 200 tyre and retracted forwards. Each main unit had an 880 x 230 tyre and, unlike the swept-wing Sukhois, retracted straight inwards. Track was 4.65m (15ft Sin) and wheelbase 5.05m (16ft 7in). The cockpit housed an ejection-seat and had a bulletproof windscreen and one-piece

|

frameless canopy sliding to the rear. Among the comprehensive avionics suite were two items with antennas in the top of the fin, the slots for the Svod (Arch) navaid and SOD-57 transponder and the RSIU-5V inside the dielectric fin cap. The wings were plumbed for drop tanks, to be carried on pylons only just inboard of the instrument booms. The planned armament was two guns (Sukhoi assumed the NR-30), and steel blast panels were pro

vided in the sides of the forward fuselage. Before the T-3 was completed the guns were replaced by missiles. The intended weapon was the K-6, to be carried on interfaces attached where the tanks would have been.

The PT-7 differed mainly in having an area – ruled fuselage, with a visibly waisted middle section, and a new ranging radar with a pointed downward-inclined radome projecting from the bottom ofthe nose. Other differences

included unperforated airbrakes and a revised fin-cap antenna which extended around the top of the slightly shortened rudder.

These aircraft were the first in what proved to be a long succession of prototype and experimental aircraft in the search for the best interceptor. This underscored the Soviet Union’s determination to accept nothing but the best, because any of these aircraft could have been accepted for production.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|